Drone strikes and border trenches: Russia’s war on Ukraine comes home

Recently built defences give us a roadmap of Russian anxiety, write Janice Kai Chen and Mary Ilyushina

Three drones buzzed through the night sky over Belgorod, a Russian city just a couple of dozen miles from the Ukrainian border. One drone smashed through the window of a sixth-floor apartment, startling a couple who were watching television. The other two crashed on nearby streets, denting parked cars and rattling the residents’ nerves.

Ten days after that event in late February, workers at an oil-pumping station in Novozybkov, a small town in Russia's Bryansk region, found a small bomb that officials said was probably dropped from a drone. Later that day, in Rostov-on-Don, a building of the Federal Security Service, or FSB, exploded in flames – the latest in a string of mysterious fires across western Russia.

More than a year after President Vladimir Putin unleashed his invasion, Russia’s war in Ukraine is also being fought on Russian soil, and Moscow is scrambling to protect its borders. The war Putin expected to win quickly now encroaches daily on the lives of Russian citizens, with frequent reports of fires, drone attacks and shelling.

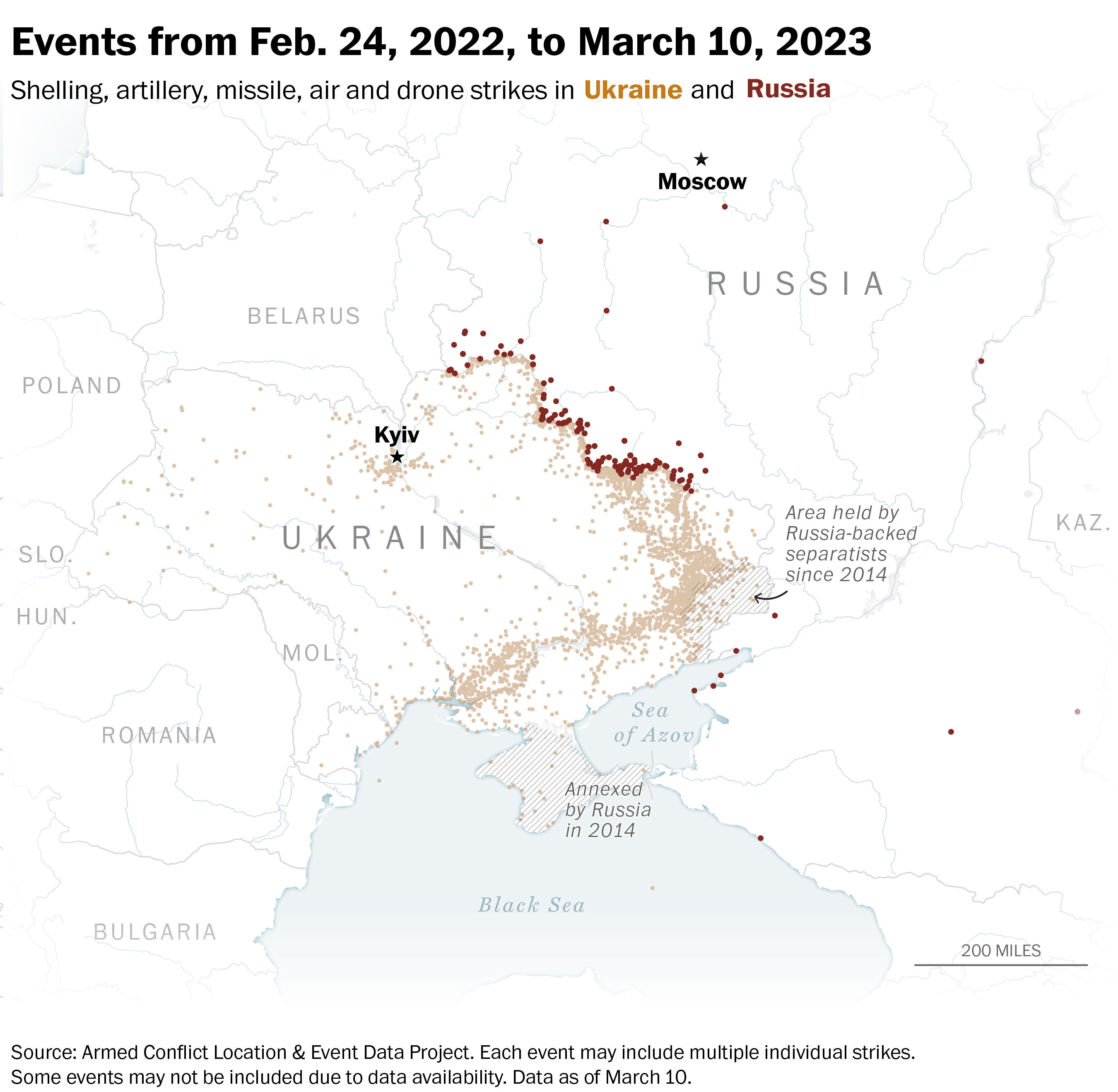

Ukraine and its citizens, of course, are bearing the overwhelming brunt of suffering in the war. More than 8,000 civilians have been killed, according to the United Nations. Millions are displaced; whole cities have been reduced to rubble.

But the longer the onslaught drags on, the more real it becomes for Russians, especially those living in border regions. Putin had hoped to shield his citizens – even from the word “war”, by calling it a “special military operation”. Now, he has ordered a tightening of border security – not in the four Ukrainian regions he claims, illegally, to have annexed – but along the internationally recognised border with Russia itself. Air defence systems are being deployed in Moscow and other locations.

Ukraine says its military is operating only in its own territory. Privately, however, officials have acknowledged a Ukrainian role in some dramatic strikes, including an explosion on the Crimean Bridge in October. In the case of the FSB fire in Rostov, an adviser to President Volodymyr Zelensky tweeted: “Ukraine doesn’t interfere, but watches with pleasure.”

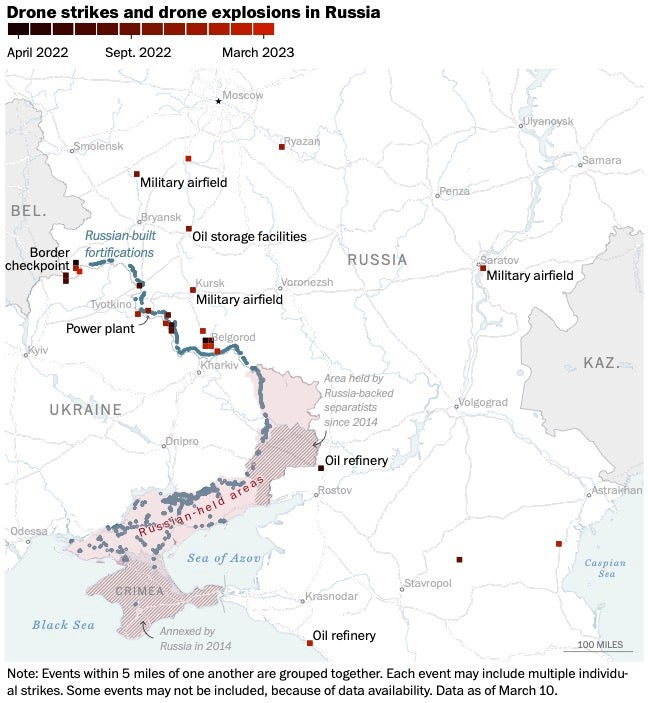

In the early months of the invasion, only sites very close to the Russia-Ukraine border were targeted by drone strikes, mainly ammunition depots and fuel tanks. Over time, the reach of these strikes has grown longer and longer, approaching Moscow.

Late last month, a military drone attempted to strike a gas compression station, a key part of the region’s energy grid, in Kolomna, about 50 miles south of the Kremlin, according to senior Russian officials.

Images of the drone posted to social media indicate it was a Ukrainian-made UJ-22, produced by Ukrjet, with a claimed flying range of 800 kilometres, or about 500 miles. The attack was unsuccessful. The drone brushed treetops and fell a few yards from the station’s fence. Still, it came alarmingly close to Russia’s capital.

In December, Ukrainian drones carried out a double strike on the Saratov Engels-2 air base, which houses Russia’s strategic nuclear bombers.

There have been at least 27 publicly reported drone attacks on high-value targets in Russia, primarily military bases, airfields and energy facilities. In some cases, drones crashed or were shot down before reaching their targets. At least three drones crashed near Astrakhan, a city close to the Caspian Sea near where Russia fires missiles into Ukraine.

A drone hit Dyagilevo airfield in Ryazan in December, and another exploded in October near Shaikovka airfield in the Kaluga region, which hosts the 52nd Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment.

The attacks have not caused widespread damage to military assets but serve to demoralise Russian forces, according to Ian Matveev, a Russian military analyst.

“When you have a drone that carries small explosives, it is unlikely to do much physical damage, but it’s a big reputational blow,” Matveev says.

The second main type of attack, Matveev says, primarily has targeted military warehouses and ammunition depots near the Ukrainian border, aiming to deplete Russian supplies.

Energy targets are of less value, he says. “The efficacy of targeting oil warehouses is probably the lowest, as Russia is a giant oil producer and it’s not possible to significantly disrupt the supplies,” Matveev says. “But you still can create local crises by targeting sites storing fuel that is urgently needed in that location.”

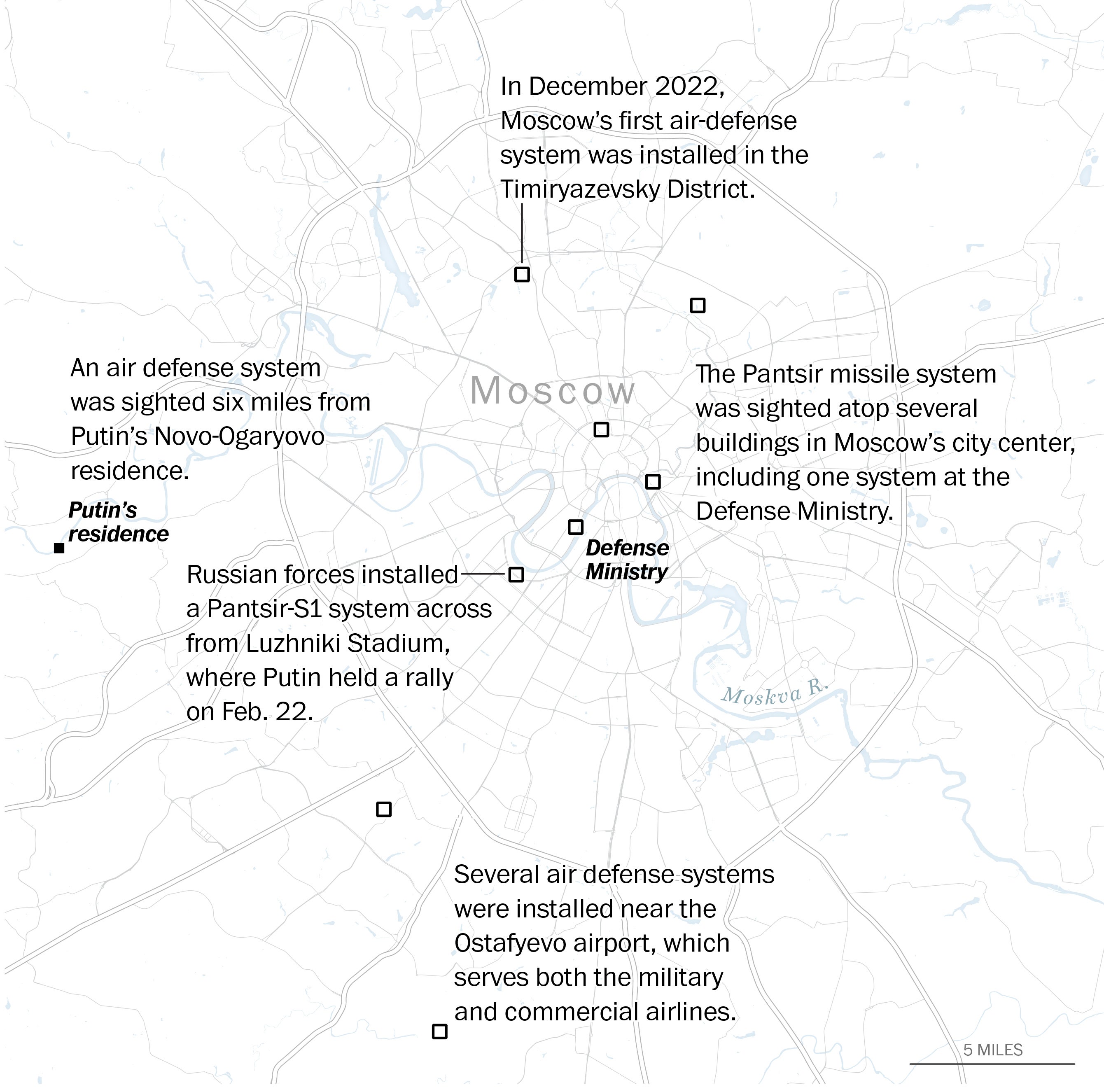

The two successful strikes at the Engels-2 airfield in December appear to have greatly alarmed the Russian leadership. Since then, Russia has deployed new air defences to protect Moscow.

In recent months, air defence systems such as the Pantsir-S1 and S-400 were lifted with heavy cranes and perched on rooftops or placed in city parks. Analysts noted that three systems in central Moscow – on the roofs of the defence ministry, the local interior ministry headquarters and a business centre – effectively form a dome over the Kremlin.

“Moscow probably has the densest air defence coverage of any city on Earth,” says Dara Massicot, a senior researcher at Rand Corp.

Beginning around mid-January, similar systems were spotted farther out in the capital.

Before the invasion, residents of a housing complex on the edge of Losiny Ostrov National Park enjoyed serene views of a forest stretching for several miles east. But in January, residents woke up to the sight of several air defence systems nestled in a clearing between a dog run and a creek.

Alarmed residents complained to the authorities, who responded by citing national security needs, reported The Insider, a Russian investigative outlet.

Placing such missile systems so close to residential areas can be dangerous, Matveev says, noting that the missiles can fly off course or detonate accidentally.

“Each has a warhead and is fueled,” he says. “Imagine if there is a fire, then what kind of blast is going to happen within the city limits.”

Since the invasion started, Russian authorities have reported more than 300 strikes involving shelling, artillery or missiles in Russian border villages and towns, and at least 40 casualties, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Some villages have been evacuated, several schools in the area have switched to online classes, and government social media pages are often flooded with pleas from unsettled residents asking to protect them from hostilities.

Local officials have blamed these attacks on Ukraine, but many happen in remote areas and there is little video evidence, making it impossible to verify the Russian claims.

Such reports, however, have been leveraged by local authorities to demand patriotic support for the war and to justify initiatives such as digging trenches and building “dragon teeth” – cement pyramids meant to stop an enemy’s ground attack – along the entire recognised border with Ukraine.

The Belgorod region, one of the main staging grounds for Russian forces, began installing fortifications as early as April 2022. The fortifications have been rebranded as the “zasechnaya line”, a medieval term referring to a line of reinforcements created on the southern borders of the Russian Tsardom in the 16th and 17th centuries to protect it from attacks of the Crimean Khanate.

Two other border regions – Kursk and Bryansk – began construction in autumn after a series of Russian military defeats. In a mini-documentary produced by a local state-financed TV station, Bryansk governor Alexander Bogomaz said the defence ministry had ordered digging to start in early December.

The cost of the fortifications is high. The Belgorod region alone spent about $132m (£107m) on the project. But military experts and even some pro-war Russian commentators agree that they are largely useless, because there is virtually no chance Ukrainian forces will launch a ground attack on Russian territory.

In recent weeks, Russia has also been actively placing similar fortifications in occupied Crimea and other territories it holds in southern Ukraine, which may suggest Moscow is afraid of losing them.

“I tend to view these things as like kind of a road map of their anxiety and what they’re worried about,” says Massicot, the Rand analyst.

Satellite imagery of two narrow land bridges to Crimea from mainland Ukraine shows recently built defences in Armiansk and Medvedivka. “The Russian military seems to understand they may have to defend Crimea in the near future,” Matveev says.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments