‘Now I have this thing called life’: How art, family and my dog helped me overcome anorexia

'My eating disorder began after a traumatic brain injury. I was 18 years old at the time. I was a jockey, and I fell off a racehorse.' Lorna Collins shares her struggle with the illness

I never thought it was possible to get “better”. After spending 18 years trapped within a dark, repeating cycle of relapse and enforced hospitalisation, with acute episodes of anorexia, my new recovery is often named “miraculous”, “remarkable” or “extraordinary”. At my lowest weight, less than 5½ stone (half my current body weight), I was teetering on the threshold between life and death. I had no reflex, I was vacant, hardly there. But here I am, now, flourishing and nourishing the brand new life I have created for myself.

My eating disorder began after a severe traumatic brain injury, which occurred when I was 18 years old. At the time, I was a jockey, and I fell off a racehorse. When a bandage became untied from the horse’s leg, he tripped and rotated. I was dislodged, and landed on my head. Bang. I stopped breathing, everyone thought I was dead. My father revived me, and I was airlifted to hospital. I fell into a coma. When I eventually woke up, I had total amnesia, and I could not remember anything about my life. A blank canvas, ready to be coloured and created anew. But I couldn’t do anything. I did not recognise anyone. I did not know how to put shoes or socks on.

I can’t remember any of this, since my amnesia continued. All I “know” about my history comes from other people’s testimony. The brain damage meant I could not retain memories. Eventually, after a while, and still very unwell, I was discharged home. My mind’s reaction to the brain’s injury was to develop neurotic and psychotic symptoms. I couldn’t control anything, I couldn’t do anything.

Reducing what I ate was natural, easy. Soon, I slipped into the restriction cycle. Another fall, some would call it voluntary, although I never chose to become unwell. I lost control, and fell into the eating disorder, heavily. Soon enough I was admitted to an eating disorder unit (EDU). Here I learnt more restriction techniques, and soon discharged myself before any sort of treatment could commence. There were other admissions, other symptoms. Doctors kept giving me different diagnoses, they couldn’t work me out: (atypical, treatment resistant) psychosis, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder, depression... I forget the rest.

Everything had evolved from the brain injury, before which I had been a happy, normal, successful teenager. My recovery from these other problems is also important, but for me all recovery starts by focusing on the eating disorder. I have learned that when I eat well and take care of myself and my body, all symptoms recede.

My illness(es) led me to be detained in a number of psychiatric hospitals across the UK, and also in France. These admissions were extremely traumatic; I learnt more about how to be ill, than well. Despite all this, I managed to complete a PhD in French philosophy at Jesus College, Cambridge (as a foundation scholar).

I also went to teach at the Sorbonne, in Paris. I worked as an academic and published various art and philosophy books. I wrote articles, I sold paintings. However, continued episodic relapses and hospitalisations were pitted within my various successes, marring any clear sense of purpose or career.

My last admission was to Cotswold House ward, in 2017, at the Warneford Hospital in Oxford. Here, I finally learnt how to be well. The ward created a unique and extraordinary difference to the experience of being hospitalised for an eating disorder. I look back on my admission as a “special” time, not just about being ill, but about opening a novel and an exciting way of living.

Before I was admitted to Cotswold House, I was close to extinction. Weak, fragile and warped by so much disorder, I was having a chronic mental and physical breakdown. At risk of collapse and further self-harm, I was admitted to the local acute psychiatric day hospital.

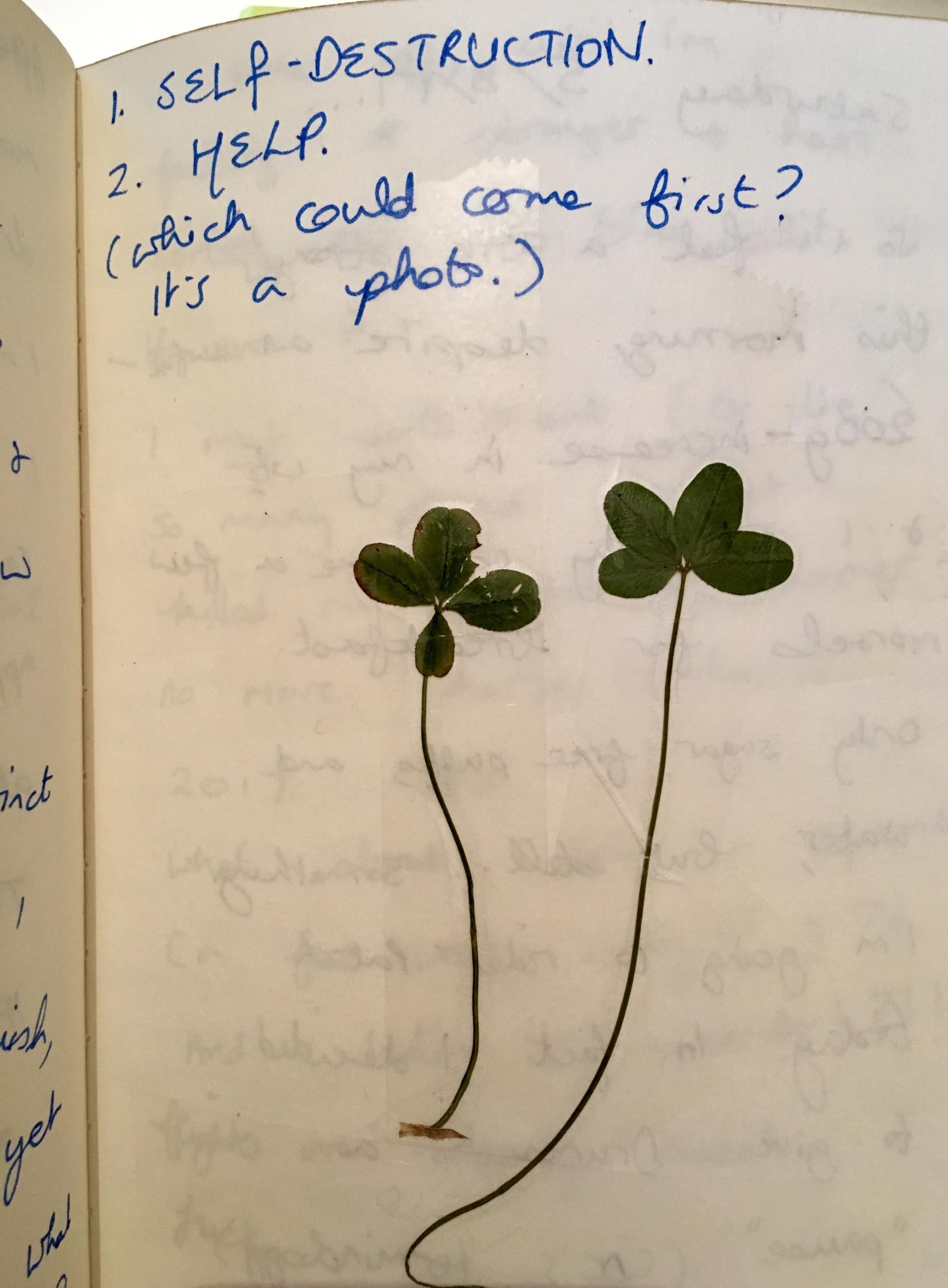

As I waited at the bottom of the drive for the ambulance to pick me up and transport me to the day hospital, I spotted two four-leaf clovers. I asked myself: what do I wish for? I asked the first clover to enable me to extinguish and destroy myself. DEAD.

That was the best solution, all round, I thought. I wasn’t sure about the second clover, and muddled with my thoughts. What hope might it bring me? Then I said, to get help.

I discovered that recovery is not a fixed, static end point. It is an ongoing process I commit to and furnish every day

This shows that inside my deeply disturbed mind, I still had the desire to get well. I didn’t want life to give me so much excruciating agony. I hoped that one day I wouldn’t have to be overwhelmed and distorted by pain. I didn’t know how life could ever be different, but I wanted it to be different.

I realised that to make it different, to decrease my pain, I needed help. I couldn’t elaborate on what “help” was but I knew that I couldn’t do it on my own. In this way, despite being severely entrenched by my illness(es), I had the insight and capacity to consider how life could be different.

Soon enough (and fortunately), I was transferred from the day hospital to the EDU at Cotswold House. Here, the breakthrough for me was my realisation that I did not have to die. Anorexia for me was to a great extent a (if slow, still accurate) form of suicide. As I starved myself, I was killing myself. Anorexia has the highest morbidity rate of any mental illness (20 per cent). I have seen three patients die on other eating disorder wards. This makes me sad and angry, because I know it does not have to be like that. You do not have to die. This is what I learnt at Cotswold House.

I discovered that recovery is not a fixed, static end point. It is an ongoing process I commit to and furnish every day. I still find some things difficult (who doesn’t). I’m working on these, both in therapy and in everyday life. I test out strategies, and problem-solving situations. I’m still making progress, and often surprise myself with how I manage to cope in difficult moments. Promptly using existing or spontaneous coping mechanisms, I carry on being.

I use my art – painting, poetry, film – to express both my most difficult issues and also to celebrate my passion for being well, being alive. In this way, I engage creativity to manufacture a crucial coping mechanism, with which I can express myself (the good bits and the bad bits). When I paint, thoughts stop and I can simply “be” in a pure, silent moment.

It’s very peaceful. I also love riding my horse, Patch, who is a mahogany and white gypsy cob and will jump anything. We gallivant around and have a lot of fun. I’m very proud of him and my dog Foxy, an exquisite rescue from Romania. She has her own career, mind you, being registered as a Pets as Therapy dog. We visit patients at local mental health centres and wards. This is a very rewarding activity. All these activities provide me with effective methods to deal with the trials and tribulations of everyday life, to enjoy life.

And now I have this thing called ‘life’, I’m determined to make it successful. I want to be known – not for my illness, but my wellness

One of the hardest parts of an admission to an EDU is gaining weight. When you are severely underweight, it changes the way your mind functions. Below the “normal” BMI (18-25) and at an anorexic BMI (under 17.5), your brain chemistry changes, so you are unable to see how underweight you are. The idea that you need to gain weight is ludicrous, since it seems as though you are already obese.

This distorted, dysmorphic vision of your body is one of the most difficult and defining symptom of anorexia. During previous admissions to other wards, I managed to convince the doctors that I did not need to put on much weight at all. The physicians then entertained this idea, and I never got to a healthy weight. I did not even know what a healthy weight was.

Often (because of comorbid symptoms, and lack of beds), I was sent to acute psychiatric wards, where I was told that I was too fat to get help from an EDU. I soon lost enough weight, and more. I stopped eating and drinking. From experience, the passport to an EDU is to be on death’s door from malnutrition. This is despicable.

At this level of malnutrition, the idea of getting to a “normal” weight might seem completely ridiculous, a nonstarter. It took me 18 years to find a method whereby I could completely rethink this view, and learn a way out of the illness. But there are still patients who totally disagree with and refuse to be “normal”, as I did, for so many years.

One of the characteristics of eating disorders is the acute repetition of relapse. Every hospital admission I have been to (around the UK), I have always known at least two patients, from previous admissions. It’s very hard to get out of the system. Sometimes patients don’t even want to. It’s somehow simpler to be sucked into the EDU bubble, away from the Real World.

Admissions to EDUs are lengthy, it’s very easy to become institutionalised. Wards are often locked; every moment of the day and night is ordered and controlled by staff. It often feels like being in a prison. Prisoners apparently reoffend at a rate of 60 per cent (for short-term prisoners, in the UK); there is a similar rate of relapse and hospitalisation for patients in EDUs.

I know it well. In previous admissions, I have been discharged when totally unstable, and nowhere near “recovery”. I was terrified of weight gain, or being anywhere near “normal” (not that I had any idea what this was). Various consultants fed this attitude, by offering such a low target weight so it appeared that having a BMI of, say, 14, was fine, normal, even. I’d be discharged.

The only guarantee was relapse. The illness was a comfort. It’s easier to be detained, locked up inside the hospital bubble, than “living” (whatever that is) in the real world. I became institutionalised, caught inside the yo-yo of discharge, relapse, restrict, self-harm, dramatic weight loss, suicide attempt, being sectioned, admitted to acute psychiatric ward, refuse food, water, medication (everything), rapid physical deterioration, chronic psychosis (amidst everything else), admitted to EDU, remain here for four to five months, put on a paltry amount of weight, continue self-harming (they made it a policy to ignore my self-harm), discharged (disturbed, disturbingly underweight), and the whole circuit went round again.

Until, finally, I learnt that I did not have to be locked, detained inside this eternal, institutionalised cycle. There was a way out – not to die, but to make a new life for myself, by opening a revolutionary new spectrum called recovery, which I had never dreamed of existing, so proximate, before.

This is an ongoing process, which I recommit to every day. However, I embody and celebrate the positives. I wish I had known about the Cotswold House viewpoint, and had access to this new help, at the beginning. It would have prevented so many years of catastrophic suffering.

And now I have this thing called “life”, I’m determined to make it successful. I want to be known – not for my illness, but my wellness. There are things to do in the world: I am reviving my career in academia, working as a writer and lecturer, I am writing a book about my recovery, I am enjoying my quality time with Foxy, Patch, my beloved family, and my dear friends.

We’re going out for a pizza, or maybe fish and chips, shortly, to celebrate. So much to celebrate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments