What was Turner’s fascination with a small, sleepy town in Switzerland?

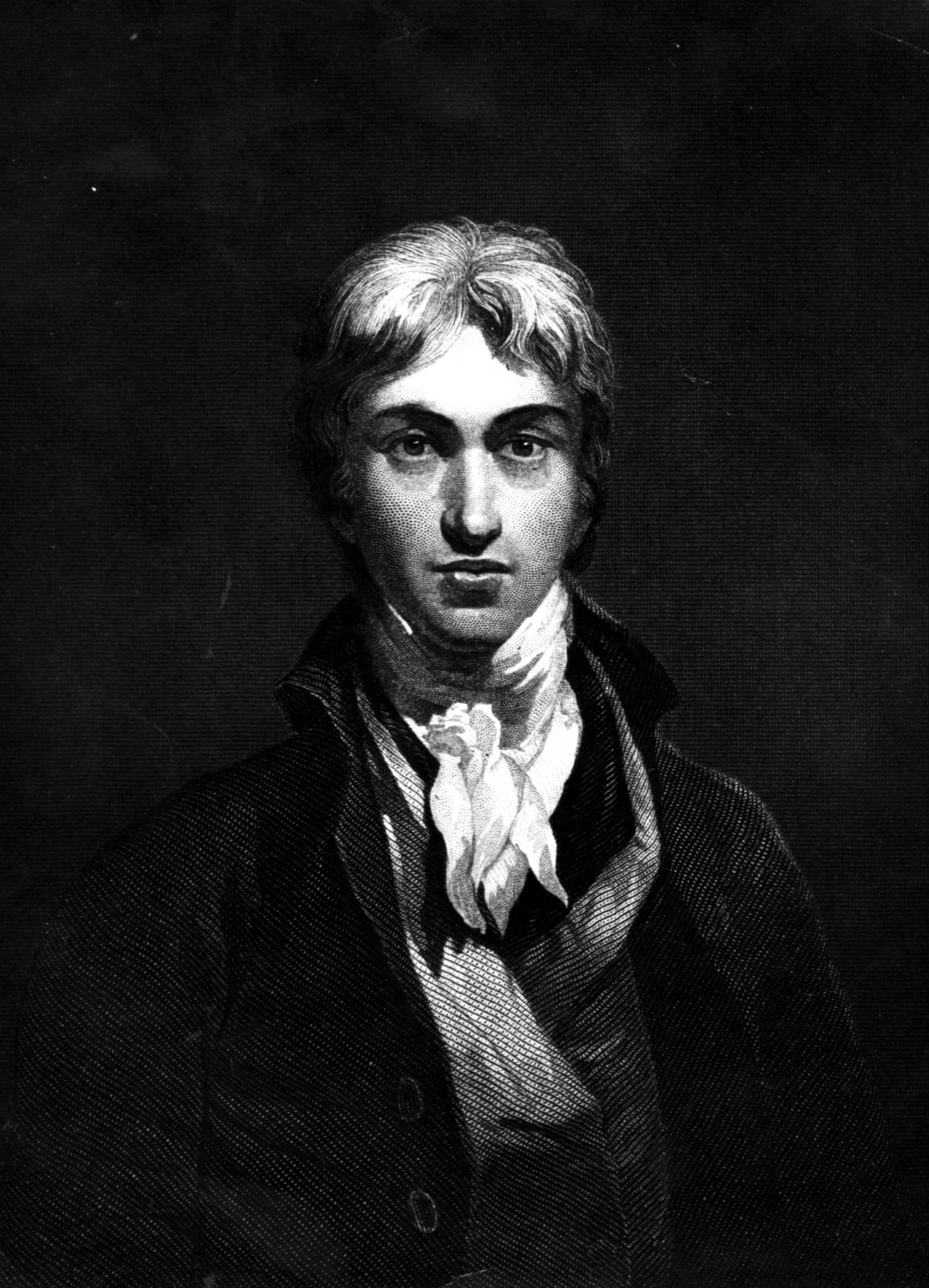

England’s greatest landscape painter visited Lucerne six times throughout his life and, as William Cook discovers, its dramatic landscape is the perfect subject for the artist’s atmospheric paintings which helped turn it into one of Switzerland’s most touristic cities

In the Kunstmuseum in Lucerne, a futuristic art gallery beside Switzerland’s most beautiful lake, the museum’s director, Fanni Fetzer, is showing me her new Turner exhibition. On the gallery walls are pictures of Lucerne as Turner saw it – a one-horse town dwarfed by the mountains that tower over it. Now look out of the window. The view he painted has been transformed. Two hundred years later, that sleepy little town has become Switzerland’s most touristic city, and the artist who made it so was William Turner.

Turner visited Switzerland six times between 1802 and 1844. He travelled all over the country but the place he spent most time, by far, was Lucerne. He loved to paint Lake Lucerne and its surrounding peaks – especially Mount Rigi, aka “the Queen of Mountains”. So why was England’s greatest landscape painter so keen on Switzerland – and Lucerne in particular? Because he recognised this dramatic landscape was the perfect subject for his dramatic paintings. “Atmosphere is my style,” said Turner – and no European landscape was more atmospheric than the rugged shores of Lake Lucerne.

Today Switzerland is widely (and quite rightly) regarded as one of the world’s most idyllic tourist destinations – a peaceful, wealthy country where the trains run like clockwork, and standards of safety and comfort are unsurpassed. Yet when Turner came here in 1802 it was a land untamed, and its people were impoverished. A war-torn wilderness in the heart of Europe, it had been a battleground for centuries. It wasn’t creature comforts which drew Turner to Lucerne – it was the wildness of the place.

This primitive vision of Switzerland was reflected in Turner’s paintings. Today, Switzerland’s public image is one of serenity and security: cheese and chocolate, expensive watches, Alpine meadows, placid lakes... this modern image is a world away from the one that Turner depicted. His Switzerland was powerful and perilous, beset by violent storms.

As anyone who’s been to Switzerland knows, both visions are entirely accurate. On a sunny day, the country can seem like paradise. When the sky darkens and the wind picks up it takes on quite a different character. Nowadays, British visitors are attracted to Switzerland by its prosperity and tranquillity. The Britons who followed Turner’s trail came here in search of excitement, inspired by the power of his pictures. Yet tourism is a destructive force, which adulterates what it covets. It was the popularity of these pictures which helped turn Lucerne into a tourist resort. “Today Switzerland stands for luxury,” says Fetzer. “Everything is clean and perfectly organised, and we’re always on time, but that’s really something new.”

Before Turner’s first visit in 1802, Switzerland wasn’t an obvious tourist destination. Even for young aristocrats who were rich enough to spend several years gallivanting around Europe on the Grand Tour, it was generally perceived to be an annoying obstacle on the way to Italy. For these gap-year toffs, Lucerne was the last place they’d think of going.

Today’s gap-year brats shun Switzerland because it’s not edgy enough. Conversely, their 18th-century predecessors didn’t go there because it was too dangerous. Riven by various civil wars in the 1600s and 1700s, in 1797 it was invaded by Napoleon. It was the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, a brief respite between the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, which provided Turner with an opportunity to visit this unfamiliar country.

After his first trip to Switzerland, Turner stayed away for 34 years. For Britons the continent was off limits throughout the Napoleonic Wars, and during the 20 years that followed, Switzerland was ravaged by internal strife. Forget that famous line from The Third Man about Switzerland enjoying five centuries of brotherly love, and only inventing the cuckoo clock. As any German will tell you, cuckoo clocks come from Germany’s Black Forest, and until about 200 years ago Switzerland was a volatile, unstable place.

When Turner finally returned, in 1836, the Swiss tourist industry was just beginning – and it was driven by the Brits. In 1811, British climbers had scaled the Jungfrau, starting a spate of Alpine ascents by British mountaineers (the Swiss were far too busy scratching a living to waste time on such frivolous pursuits).

Turner didn’t come to Lucerne on his second visit to Switzerland. Instead, he travelled around Lake Geneva, where Byron and Shelley had spent a stormy summer in 1816 (they nearly drowned during a voyage on the lake). During their stay, Byron wrote an epic poem called “The Prisoner of Chillon”, inspired by a visit to Chateau Chillon, at the eastern end of the lake. Byron’s poem was hugely popular, drawing countless tourists to Lake Geneva, in much the same way that Turner’s paintings drew tourists to Lake Lucerne. Back then Chateau Chillon was remote and inaccessible. Today it’s besieged by coach parties, even though no one seems to read Byron’s poetry anymore.

A more enduring work of fiction to come out of that wet and windy summer was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, written to while away the time when the weather was too bad to venture out of doors. Frankenstein was conceived on Lake Geneva but, like Turner, Mary liked Lake Lucerne best. Like Turner, it was the drama of the lake, not its placidity, which attracted her. “These sublime mountains and wild forests seemed a fit cradle for a mind aspiring to high adventure and heroic deeds,” she enthused in 1814.

For Byron and the Shelleys, creativity was a by-product of their travels. For Turner, it was the raison d’etre. His trips to Switzerland weren’t idealistic flights of fancy – they were shrewd moneymaking schemes. France, Italy and the Netherlands had already been painted extensively by leading artists – Switzerland hardly at all – yet with the dawning of the Romantic movement, interest in this Alpine land was growing. An astute businessman, Turner had spotted a good business opportunity. “He was not discovering Switzerland,” says Fetzer. “He knew exactly where he wanted to go.” The small watercolours he painted on his visits were arranged in albums by his agent, who showed them to prospective buyers, to entice them to buy bigger versions in oils (less well-heeled customers could make do with an engraving).

Turner returned to Switzerland for a third time in 1841, and this time he made a beeline to Lucerne. He stayed at the Schwan Inn (it’s still there, though now a restaurant, rather than a hotel). From his hotel window he could look right down the lake, towards his favourite peak, Mount Rigi. He painted this mountain obsessively. Dozens of pictures survive, and many of them are in the exhibition. One of which, The Blue Rigi, set a British record for a watercolour when the Tate bought it for £5m in 2007.

Mount Rigi isn’t the most spectacular mountain in Switzerland. It’s not even the most spectacular mountain on Lake Lucerne. At 1,800 metres, it’s not especially big by Swiss standards. Mount Pilatus, on the opposite shore, is several hundred metres higher. So why did Turner prefer Rigi? Partly because it was a splendid subject, changing colour in the changing light (he painted a Red Rigi, as well as his record-breaking blue one) but also because it was more attractive to the people who mattered most – his customers.

Turner’s choice of Mount Rigi was a clever bit of business. Unlike Mount Pilatus, it was relatively easy to walk up Rigi, and (thanks in no small part to the popularity of Turner’s pictures) it soon became a popular excursion. The fashionable thing to do was to walk up there in the small hours, and see the sunrise from the summit. What better memento of your trek than a painting by Turner (or an engraving, if you weren’t quite so flush)?

Despite the commercialisation, the endless crowds and queues, somehow the image of Switzerland that Turner saw, and captured in paint, endures

Turner never walked up Rigi – he was far too busy painting it. In that respect, he had more in common with the indigenous Swiss than the British visitors who bought his paintings. As the tourist trade took off, locals gravitated to this new industry, working as tour guides and hoteliers. For these Swiss natives, like Turner, tourism was a commercial venture.

However Turner was no hack. He wanted to sell his paintings, but he never pandered to his punters. A lesser artist might have omitted signs of modernisation in Lucerne, to create more marketable pictures. Not Turner. He was interested in reality, not fantasy. The first steamboats appeared here in 1837. They also appear in Turner’s paintings. As he said himself: “My business is to paint what I see.” “He’s very interested in modern life,” concurs Fetzer. “He’s not longing for pure nature, without human beings.” She shows me a Turner landscape, featuring one of these steamboats. “This is a very atmospheric painting, but it’s not an idyllic view, like the story of Heidi.”

Turner visited Lucerne three more times, in 1842, 1843 and 1844. He’d spend the summers here, and the winters back in London, in his studio, working up his sketches into finished paintings, which he’d exhibit at the Royal Academy. By the time he made his final visit, Lucerne was no longer a sleepy backwater. Those industrious, canny Swiss had seen what British sightseers wanted, and had set about providing it. A year after Turner’s final visit, in 1845, the Schweizerhof opened in Lucerne. It was the first of Switzerland’s grand hotels.

Turner’s paintings weren’t the only drivers for Lucerne’s growing appeal to tourists. Theatre and music also played leading roles. Lake Lucerne was also the setting for Schiller’s play, William Tell (written in 1804) and the opera of the same name by Rossini (written in 1829). Tell was a perfect poster boy for the Romantic movement – a humble rebel fighting against autocratic despots in the most romantic setting any artist could conceive.

And yet this romantic longing for unspoilt idylls went hand in hand with the emasculation of the landscape that painters like Turner (and poets like Byron and Shelley) so admired. “A lot of the wealth of the country comes from tourism, and this romantic idea that landscape itself is interesting and beautiful,” says Fetzer. The landscape around Lucerne is still interesting and beautiful, but it’s a lot tamer now than it was in Turner’s day. Would Turner mind? Would he care? “I’m not so sure he was so romantic,” says Fetzer, with a chuckle.

By now Turner was nearly seventy, and no longer strong enough to endure the gruelling journey to Switzerland. He died six years after his last visit, in 1851, aged 76. In the years after his death, Swiss tourism exploded. In 1859 the railway reached Lucerne, linking the lake to cities throughout France and Germany. In 1863 Thomas Cook organised his first package holiday to Switzerland, opening up this remote hinterland to Britain’s emerging middle classes.

In 1865 a road around the lake was built (before then it was quicker to travel by boat) and in 1866 Richard Wagner moved into a lakeside villa, just outside Lucerne. “Wherever I cast my gaze, I am surrounded by a magical world,” he wrote. “I know of no other home earth more beautiful, indeed none more comfortable than this.” Turner never would have called Lucerne comfortable. Within half a century of his first visit it had become so.

In 1867 Mark Twain came to Lucerne, to hike to the summit of Mount Rigi. He wrote a book about it, attracting American visitors to Lucerne. In 1868, Queen Victoria followed in his footsteps – well, sort of (she was carried up there). In 1871 Europe’s first cog railway rendered such exertions unnecessary, taking 130,000 sightseers to the summit in its first year alone.

Today Lucerne is invaded by ten million tourists every year. For a city with a population of 100,000, that’s a hundred visitors for every resident. The streets are full of tour groups, the lake is crisscrossed by pleasure boats. So has tourism ruined Lucerne? Not really. Tourism has transformed a poor town into a rich city, and the same thing has happened all over Switzerland. Before the first tourists arrived Swiss families had to sell their sons as mercenaries to fight and die in foreign wars, because they couldn’t afford to feed them. Now, Switzerland has to import foreign workers from abroad.

The reason British purists moan about mass tourism in Lucerne is that we’re not top dogs anymore. When Britain started the Swiss tourist trade we were a lot richer than the Swiss and our money went a long way. Now Switzerland is one of the world’s richest countries, per head of population, with a GDP (per capita) about twice that of the UK. Middle-class Brits used to be able come here and live like kings. Now we have to count the pennies. We used to come here for months on end. Now we come for a long weekend.

When I first came to Switzerland, 35 years ago, the golden age of Anglo-Swiss tourism was already long gone, but a pound still bought three Swiss Francs. Now it’s barely 1.2. I still love coming here, but when I’m here I live simply, like the Swiss do – no-frills hotels, public transport, picnic lunches in the park... Today’s top dogs are the Arabs, the Asians and the Chinese. They can afford to spend a whole summer here, like the British used to do. No wonder we sneer at Chinese tourists sending selfies of their new Swiss watches (complete with price tag) to their friends and families back in China. We used to be able to flash the cash here, and now we can’t. And it hurts.

Yet despite the commercialisation, despite the endless crowds and queues, somehow the image of Switzerland that Turner saw, and captured in paint, endures. “If you get up early in the morning and take the first boat, at 6.15, from Lucerne to Weggis, you have exactly this view,” says Fetzer, as we stand before a Turner watercolour, painted two centuries ago. “The weather is the same, the light is the same, the lake is the same.” She’s right. I’ve been on that boat many times, and I’ve always admired the view, but after I saw Turner’s paintings of it I marvelled at it. And that’s the difference. A good artist sees the world as it really is. A great artist enables us to see the world in a new and different way. Those lakes and mountains were always there, but we never saw them quite so clearly until we saw them through Turner’s eyes

Turner: Das Meer und Die Alpen (The Sea and the Alps) is at the Kunstmuseum Lucernee (www.kunstmuseumLucerne.ch) to 13 October. For more information about Lucernee and Switzerland, visit www.myswitzerland.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments