True crime pays: the history of real-life crime magazines

The public appetite for real-life crime stories stretches back a lot further than TV documentaries such a ‘Making A Murderer’. David Barnett charts the history of the true crime magazine

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Whenever official crime figures are released, there is often some side-discussion about how the “fear of crime” often paints a bleaker picture than the actual statistics themselves. And it’s true: we all do fear falling victim to crime, which is why we take care when walking down darkened streets, why we install burglar alarms on our homes, why the BBC’s reconstruction programme Crimewatch tells us “don’t have nightmares” at the end of every show.

But the flip side of that is that we’re also actually rather obsessed by crime. Not just Broadchurch, or the latest drama from the US, or the new Rebus novel by Ian Rankin, but proper murders, actual rapes, real robberies – what has come to be known, in all its multimedia forms, as true crime.

From the books that have their own section in most bookshops, to the Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer, to the internet podcast Serial, true crime is finding ever new and inventive ways to thrive.

The public appetite for crime is as old as journalism itself. The first proper newspaper could be said to be The Daily Courant, a single-sheet news flyer that debuted in 1702. By 1714 there was a book available for sensation-hungry readers entitled A Complete History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, Shoplifts and Cheats of Both Sexes.

But really, we can pinpoint the birth of what we now accept to be true crime – detailed reportage of real criminal incidents – as 1924, when American publishing magnate Bernarr Macfadden unleashed upon the world a magazine called True Detective Mysteries. It began with fictionalised retellings of crimes, but Macfadden swiftly realised there was a hunger for straightforward and agonisingly detailed stories that were entirely factual, and within a few issues this is what he began publishing, soon dropping the pulp-like “Mysteries” bit of the title to create what would become a phenomenon: True Detective.

The magazine spawned dozens of imitators as readers lapped up the no-holds-barred reports. Issues invariably featured a woman being menaced on the front cover, usually bound and/or gagged, her dress often torn to reveal enticing acres of flesh. The cover lines matched the illustrations in terms of salaciousness. Anyone who thinks clickbait is a modern phenomenon need only cast their eyes over a few True Detective covers, which became increasingly more lurid as the magazine thrived from the 1930s to the 1950s. “She was a prisoner of two ruthless men: ‘I begged them to kill me!’,” screams one. “Exposing: Sensational Secrets of a Mail-Marriage Siren,” says another. “Riddled Brunette in Pink Pyjamas”. “Bloody Trail of the Lolita Lovers”. “The Woman-Hater Who Had To Kill”. So it goes.

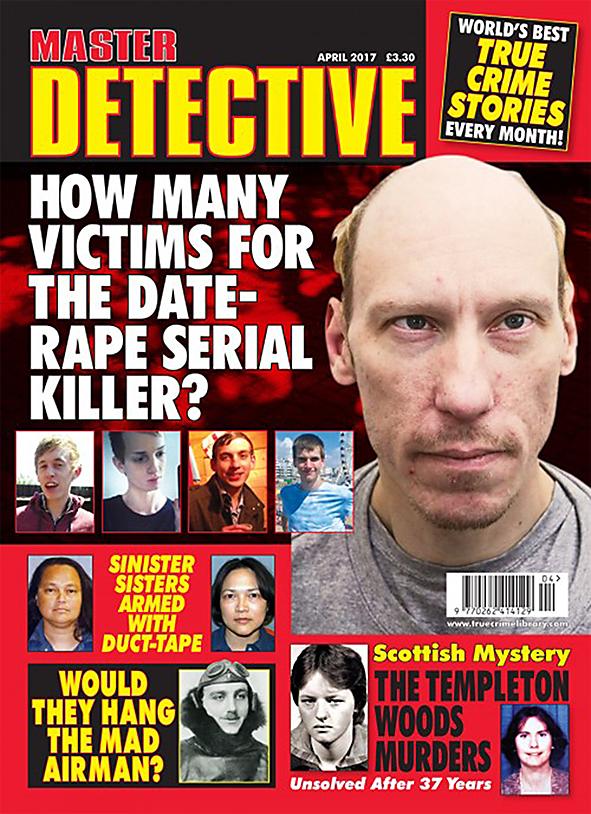

By the 1970s, the illustrations had morphed into staged photographs of minidress-wearing teens that lent the magazine and its many imitators and even more pornographic style. By the mid-Nineties the magazine had fallen out of favour and folded, but only in the US. Since 1950 the magazine and its stablemate Master Detective had been licensed by a British publisher, and these continue to deal out deadly real-life dramas on a monthly basis.

Philip Morton, who’s on the editorial staff of True Crime Library, which publishes the magazines, says: “At first the UK editions consisted almost entirely of reprints from the American titles, but gradually more and more UK cases began to be covered as well, which necessitated building a stable of UK-based writers. The British titles have outlived their US parents and have been published every month since 1950, acquiring some sister titles along the way: True Crime launched in 1981 and Murder Most Foul launched in 1991.”

Consider the latest edition of True Detective. The helpless women have gone, to be replaced by composite images mainly featuring criminal mug shots. But the shout lines are as inventive as ever: “About five minutes ago… I KILLED THIS WOMAN”. “The strange death of beautiful Florence.” “Who did murder paperboy Carl Bridgewater?” But it seems that the magazine’s readers are not just interested in the gory details, but want some kind of justice as well. Morton says, “Murder is the most ‘popular’ crime in our magazines, particularly if it's followed by justice and retribution in the form of execution. There seems to be a strong feeling among the readers who contact us that criminals should be made to pay, especially killers. That's one form of satisfaction that I believe our readers derive.”

That's understandable, but there must be more than a desire to see justice served behind the ongoing fascination with true crime. Isn’t it all about, well, a salacious need for the gory details?

Fozia Mir, a lecturer in criminology at Middlesex University, says: “Non-fiction crime books, documentaries and podcasts offer an escape for readers and listeners and are also entertaining. What could offer more escapism than reading about someone like Dennis Nilsen who dismembered his victims body parts and flushed them down the toilet, or Jeffrey Dhamer who made a shrine of his victims skulls? These crimes are so alien to us and reading about them satisfies our appetite for finding out what factors make someone commit such heinous acts.

“But there are moral and ethical issues where real life events are documented and that means a moral responsibility on those involved to report accurately, even though crime is packaged to be entertaining. Crime is not only packaged by the creators of documentaries and authors of books. Most of our understanding about the crime problem is informed by the news media, offering reports about 'who is the offender?' and the crime rate – both of which affects our understanding and fear of crime.”

Morton says: “We are very careful about the sensitivities of anyone who has been involved in any of the cases we report – especially the recent ones. We are generally more careful than the national press, for instance, about naming friends and relatives of criminals and victims, and are very selective about the pictures we use: we've no interest in causing additional grief to anyone in any of our case reports. We are committed to getting it right and telling a complete story. That way there's less chance of anyone feeling hard done by.

“Also I think people like to put themselves into life-and-death situations and imagine how they'd react -- and our magazines, which are scrupulously truthful and as accurate as we can make them, certainly provide the material for such fantasies. What's it like to be on Death Row, awaiting execution, or facing down a homicidal maniac, or indeed planning the perfect murder? Our writers specialise in putting our readers in just such situations, where they can experience a vicarious thrill.”

It’s impossible – in fact, remiss – to discuss the true crime genre without mention of Truman Capote’s 1966 book In Cold Blood. Utilising the techniques of the novel, Capote told the story of the brutal murders of the rich Clutter family by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith in Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959. Capote, initially accompanied by To Kill A Mockingbird author Harper Lee, conducted dozens of interviews and pored over official reports to create what was described as a “non-fiction novel”, which took him six years to complete. Rightly regarded as a classic, In Cold Blood, along with the 1974’s Helter Skelter (about the Manson Family murders written by the prosecutor in the case, Vincent Bugliosi) kick-started the modern True Crime book genre, which is now awash with fresh titles on a weekly basis.

While True Detective established the form, and In Cold Blood revolutionised it, there are still constant innovations in the genre. TV, of course, is no stranger to true crime documentary, but that, too, has evolved in recent times. Making A Murderer is a 10-part documentary series that debuted on Netflix in December 2015. Rather than rehash existing documents and reports, it took a different stance, in effect reinvestigating the case of Steven Avery, of Wisconsin, who had served 18 years for sexual assault and attempted murder before being freed after new DNA evidence came to light, and then arrested and prosecuted for a wholly separate murder. The series cast doubt on the whole case, especially the involvement and conviction of Avery’s nephew, Brendan Dassey, which resulted in an order for a retrial.

An even bigger cultural shift came with the 2014 podcast Serial, in which Sarah Koenig investigated, over multiple weekly episodes, the murder of Baltimore student Hae Min Lee and the conviction of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Masud Syed, on which doubt was cast.

Fozia Mir adds: “True crime podcasts, including Someone Knows Something, Crimefile and of course Serial, which put true crime podcasts on the map, offer an added dimension that you don't get from books or television. If you are an auditory person, I would say that podcasts would have a greater impact on you than books or documentaries Because the listener is not able to see real images as you would on the television he/she constructs their own images which may be more powerful.”

Podcasts have captured the attention, perhaps in a way that the same material presented in the written word might not have done for the internet generation. Australia’s biggest crime podcast is Casefile, presented by an enigmatic, nameless host who agreed to be interviewed anonymously.

He says: “Casefile is a true crime podcast that started out of my spare bedroom, and still runs out of my spare bedroom. The idea behind it was to create a true crime podcast that took a more in depth storytelling approach, with attention to detail. “The Hardcore History podcast was a huge inspiration, I wanted to take that approach of detailed storytelling and research and bring it to true crime. With each episode the amount of listeners slowly grew until suddenly it exploded. Which is amazing, as we are completely independent, with no backing from anyone. We grew from word of mouth. What started with just me, has grown to a team of five.

“The podcast format is fantastic as there is so much freedom. We don't have to pad out a story to meet a certain episode length time and on the flip side we don't have to cut anything out in order to fall into a time limit. If it takes 20 minutes to tell a story, so be it. If it takes five hours, we can do that too. And the best thing about it is, anyone can start one from home. All you need is a mic and some recording software and you are on your way.”

Though the method of storytelling has changed over the almost-century since True Detective magazine was launched, the basis of it is still the same: a fascination with the worst of human nature. It might be that the true crime genre allows us to study the depths that people can sink to, at a safe distance, or it might just be that we really, really like the juicy details of a particularly gory crime. Whatever it is, it’s not going away. But even though these stories are real, in the hallowed words of Crimewatch: please don't have nightmares.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments