It's time to accept that time is real – but there are ways to briefly delude ourselves that it can be escaped

Andy Martin considers whether the cosmic constraints humanity places upon itself are pointless

“Timeless”. It’s probably one of those words I use far too often. A piece of music is “timeless”, a book or a film is “timeless”. Once upon a time newspaper editors used the word “timeless” to signify that they were putting an unpublished article “in a very deep, dark drawer, and it may never in fact see the light of day”. As if it belonged in a different dimension, more ethereal, wasted on mere mortal readers. That’s how I liked to think of it anyway. It was an accolade of sorts. Almost on a par with “awesome”.

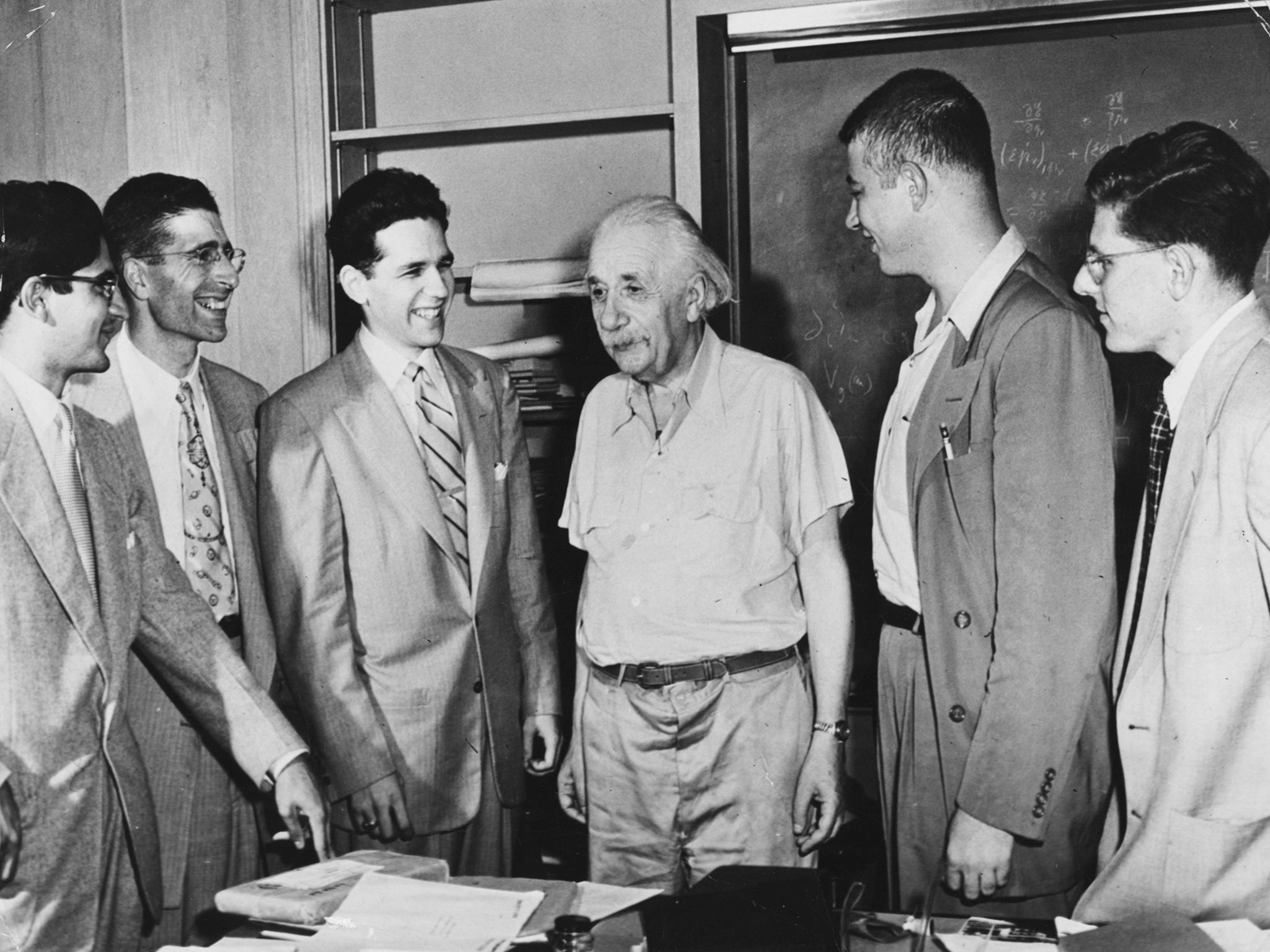

All of which to some extent explains why Stephen Hawking and Albert Einstein are so popular. You didn’t really need to read A Brief History of Time, Hawking’s classic work of cosmology, because merely holding it in your hand was enough to make you feel as if you had somehow transcended terrestrial constraints. All you had to do was buy the book. The publishers were happy either way. You had this strange sense of flying high above time and space, seeing it all laid out below you, as if you were in a plane, between time zones, floating free, momentarily liberated from gravity, entropy and death. In an intellectual sort of way, it was like being taken up to heaven or shot through a black hole and out the other side into a better place. Similarly Einstein. This is the ultimate paradox of relativity theory: that by contemplating relativity, you become a supremely non-relativistic being, no longer handcuffed to a particular location or speed, but rather overseeing the totality, grasping it as a single entity.

But the whole problem of modern cosmology, according to the brilliant theoretical physicist, Lee Smolin, is that the cosmologists themselves think in mathematical terms, as if the laws they were describing were beyond time. You don’t have to be deeply acquainted with quantum mechanics to get this. Anyone who ever did geometry at school will recall that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees. Or that the circumference of a circle is 2πr. The point about these rules is that they always apply, anywhere and everywhere. A square is always a square, a pentagon always has five sides, by definition. This is truth, at the level of tautology. And physicists, argues Smolin in his neo-existentialist Time Reborn, steep the object of all the theories, the cosmos itself, in the properties of the language used to give it expression. But mathematics, although beautiful, is not real. Survey the universe, if you will, and find me a “point”, for example. It can’t be done. The universe is, in fact, pointless.

Sir Isaac Newton, once described as the “last alchemist”, with his concept of absolute time, saw his scientific work as providing ballast for his theology. But even contemporary physics tends towards metaphysics, because time is dissolved right out of the equation. General relativity absorbs time into “spacetime”, which is a form of geometry, and therefore timeless or time-reversible. The “arrow of time” can seem to go either way, without making a lot of difference to anything. There is no “t” in e=mc2, for example, and mere mass gets transmuted into very speedy bands of radiant light or pure and unconstrained explosions of energy. The experience we have of time passing (and thus living and dying) is dismissed as unreal.

In his earlier The Trouble With Physics, Smolin argued that string theory (everything is made out of tiny pieces of vibrating string) was an emperor with no clothes, devoid of any empirical or testable content, and therefore unfalsifiable. He was kind of annoyed that string theory had more or less taken over whole faculties and institutions and that hard science was becoming soft and conjuring up lyrical variations on the music of the spheres. So too, in Time Reborn, he thinks that modern physics has been distracted by mathematics into eliminating linear time, and thus the idea of a beginning, middle, and end, from its vision of the universe, and that it needs to put it back in again if it is ever going to have an objective correlative or any loose connection to lived experience.

But the appeal of a celestial Shangri-La is not limited to mathematics. Rather mathematics is a formal expression of our overriding imperative to overcome time. Physicists and poets are complicit in what is one of the grandest intellectual conspiracies of all time. The ambition of so much literature and philosophy is spelt out in the title of the essay by Jorge Luis Borges: A New Refutation of Time. This is what so many writers set out to do, to refute or resist mere time, as if it was an illusion, a delusion, a form of bewitchment from which we can be set free. I agree with Smolin that it is high time for time to make a comeback.

I remember that Richard Howard, the translator, reckoned that the opening sentence of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, should not be (as it was originally translated) “For a long time I used to go to bed early”, but rather, “Time after time I went to bed early”, in order to reflect 1. Proust’s use of the word “Longtemps” as the first word of his roughly one million words and 2. the pre-eminence of the theme of time in the work overall. But if time is there it is largely in order to be (as Borges would say) refuted. The seductive evocation of Marcel’s experience, as a grown-up, of dunking the “petite madeleine” in a cup of tea, tasting it and being carried back to “Combray” and that period in his life when, of a Sunday morning, his aunt Léonie would give him a little taste of the small cake, that she had dunked in her tea, is perhaps the literary moment par excellence. Proust describes not a moment in time but a moment out of time, beyond time, a moment of pure timelessness: “I had ceased to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal.” He seems to have escaped linear time and rejoined some higher plane or lost dimension akin to eternity. Henri Bergson (the philosopher who most influenced Proust) used the term “duration”, but I think it must have been something like this that Carl Jung had in mind when he spoke of “synchronicity”.

Kurt Vonnegut, in his indispensable short novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, half recollection of the Second World War firebombing of Dresden, half science fiction adventure, imagines his hero, Billy Pilgrim, being transported off to the planet Tralfamadore, where the Tralfamadorians are amazed at how limited poor old Earthlings are in their outlook. Tralfamadorians are semi-omniscient and can see all the way around time and space, whereas little Billy is locked into his own narrow coordinates and actually ends up in a cage (albeit with a fantasy woman to keep him company). In what must be one of the most inspired metaphors in the whole of literature, Vonnegut asks us to imagine what Billy’s perception must look like from the Tralfamadorian point of view and it comes out like this: he is (in effect) strapped to the back of a flatcar going across a desert on a straight track, his head encased in a metal sphere, allowing him to see out with only one eye, but welded to the eyehole is a long piece of pipe, and whatever he sees at the end of the pipe he says to himself, “that’s life”. Whereas the Tralfamadorians, in contrast, see it all – no flatcar, no pipe, nothing but a pure and uncluttered view of everything, unlimited in their range of knowledge, effectively godlike.

I was reminded of this when I went to see Arrival, a science fiction film something like the opposite to Alien. I am limited in what I can say if I am not to give away the entire plot of the thing, but suffice it to say that the amiable heptapods, who have a non-linear language and squirt ink all over the screen and park their incomprehensible vehicles silently 10 yards above the earth, are also non-linear in their experience of time and space, just like the Tralfamadorians. And the film allows itself to become Tralfamadorian in structure, so that as Jean-Luc Godard said of his own work, it has a beginning, middle and end, but not necessarily in that order.

JB Priestley, who died in 1984, in his play An Inspector Calls (which has just come off a long run in London) thinks of time in terms of circularity and return. Linearity is a mistake. Maybe it’s something to do with theatre itself, in which you are (unless you fold after the first night – and excepting fluffs) reiterating the same script many times over. The player struts his hour upon the stage, not just once but time and time again. Eternal recurrence dramatised. In Over the Long High Wall, Priestley says that if I have a dream of a monkey jumping on me from a tree in Regent’s Park and the very next day a monkey (which has escaped from the zoo) indeed jumps on me as I’m strolling across Regent’s Park, it is because I am part of a freewheeling collective unconscious not anchored in time, and when I die heaven will be the possibility of revisiting my best and finest experiences, and hell would be repeating all the worst moments, for ever and ever, amen.

But all this relies on erasing time from the equation. And the thing we need to remember is this: this is Hollywood (in the case of Arrival) or fiction. This is the dream factory at work. This is what sells. We all fantasize about a realm beyond the real. In the ideal Platonic realm of perfect forms, everything you once lost you can get back again. I suspect this fundamental desire underpins the success of that “timeless” Jackson 5 song, “I Want You Back”. Don’t worry, in this revised, enhanced, shiny world of music and poetry you will indeed get back the woman/guy/whoever/whatever you foolishly allowed to get away from you the first time around. And every contemporary thriller implies an omniscient narrator who stands outside time and knows all and will, ultimately, in a godlike way, reveal all (no wonder we revere and perhaps over-hype writers).

We only think in this way because we can. The dream of eternity is a projection of our neurocognitive circuitry. Eternity is right there, in your brain, because, in our two-phase system of thought we can process information in a stream, successively, sequentially, or we can roam around and shuffle the pack in some completely different order to suit ourselves. When we do it well, it’s genius. When we get it wrong, it’s dementia.

Every sentence, every equation, every symphony or song, existing in time, relies on memory and our synthesising of information, since you have to be able to hark back to the beginning by the time you get to the end – which is why the long and winding Proustian sentence is often so fiendishly difficult. Maybe that’s all the universe is – a very long sentence where you are lost in the middle and have no idea what it all means. It’s still linear though, even if with a lot of digressions and subordinate clauses.

Evolution is nothing but time plus mutability. Ugly old linear time is not an illusion, it is just the way things are, the way we are, the way the universe is. This and other universes, if they exist at all, must be in time and not out of it. The advantage is there are surprises; the downside is the constant disappointment. Maybe it would be a good idea to get used to it. But I guess we never will. And when I say that it has a strange feeling of timelessness to it.

An Impractical Guide to the subjective experience of escaping time (briefly):

- Read (actually read) A Brief History of Time.

- Dip a petite madeleine in a cup of tea and see what happens.

- Listen to the Adagietto from Gustav Mahler’s 5th Symphony.

- Try to think about what time is.

- Get yourself a DeLorean gull-wing car and fire it up with a lightning bolt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks