The history of TV political debates may have acted as a warning to Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn

One of the oddest things about the now-torpedoed leaders’ debate on Brexit is that they basically agree – though neither would much like to admit it, says Sean O’Grady

Will we ever get to see the big fight? Corbyn vs May, that is.

OK, so it’s not much of a follow up to Tyson Fury vs Deontay Wilder, but it might have its moments. However, while it is quite common for the politicians to pull out of TV commitments, in this case it was the BBC and ITV who withdrew offers to stage the leaders’ proposed debate on Brexit: another unprecedented moment prompted by the EU withdrawal rollercoaster. Strange days indeed.

Still, Sky News remains an option – or maybe a backstop – for the party leaders, and a head to head may yet transpire, if not in advance of the Brexit vote then for the next general election – which may arrive more quickly than many assume.

Jeremy Corbyn v Theresa May, then. Who would win? Why? What’s the best advice for each of the contenders? Will they ever decide whether Strictly or I’m a Celeb is more crucial to the national interest?

History, at least, suggests a Brexit debate might have its moments, even if the likes of Boris Johnson are not allowed to join in; and there are plenty of precedents to act as warnings and encouragements, mainly from America, where such events have been a broadcasting mainstay for a very long time.

It is probably not a good idea, for example, to open your “pitch” to the audience with: “Who am I? What am I doing here?”. Such was the opening gambit adopted by the hitherto – and hithersince – obscure Admiral James Stockdale (Retired), vice-presidential candidate chosen as Ross Perot’s running mate in his independent campaign for the White House in 1992.

With his mop of snowy white hair, old sailor’s stories about bombing the hell out of North Vietnam and his malfunctioning hearing aid, Stockdale’s was simply the most pitiable performance of any figure running for high office. When the hearing aid failed it was difficult for him to understand the questions and made him seem doddery. He was up against the dull-but-competent Al Gore and dull-but-infantile serving vice president Dan Quayle, and Stockdale acted as a sort of light relief, like the BBC Radio 4 comedy character Count Arthur Strong.

Where do you think Theresa May is tonight? Take a look out your window. She might be out there sizing up your house to pay for your social care

Even so, in the end Stockdale and Perot managed to persuade almost one in five Americans to entrust them with the task of leading America into the 21st century rather than Bill Clinton or George HW Bush. Which may prove something – some might, for instance, see Perot’s no-nonsense, straight-talking billionaire businessman shtick a distant precursor for the populism of Donald Trump.

Lacklustre as they usually are, neither Corbyn nor May should match poor James Stockdale’s low points and in fact he was a genuine war hero, and hardly deserved ridicule.

This putative May-Corbyn Brexit “debate” was a curious thing in many ways. Last year, during the general election, the prime minister went out of her way to find any excuse not to take on the Labour leader in a television studio – it was left to Amber Rudd to attend, only 48 hours after the death of her father. Whatever dramatic tension might have emerged between Rudd and Corbyn was suffocated by the attendance of Caroline Lucas (Green), Angus Robertson (SNP), Paul Nuttall (Ukip), Leanne Wood (Plaid Cymru), and, not forgetting, the Lib Dems’ Tim Farron – the “seven dwarves” debate.

Farron had probably the best line of the show – “Where do you think Theresa May is tonight?

“Take a look out your window. She might be out there sizing up your house to pay for your social care.”

May’s absence damaged an already faltering campaign, and her excuse for not attending looks even lamer nowadays – she preferred “taking questions and meeting people” on the campaign trail rather than “squabbling” with other politicians.

She’s been squabbling with other politicians ever since.

In 2017, in other words, Ms May avoided a debate which would actually have had some purpose because the people watching it each possessed a vote in the general election.

In 2018 she volunteered to engage in such a national TV debate, even though the audience watching will not have a vote on the issue at hand – or least haven’t been given one yet.

It’s a funny old world.

The conventional wisdom is that the incumbent prime minister or president usually suffers from disadvantages, and is therefore often unwilling to take up an invitation to go to toe-to-toe in a studio with would-be successors.

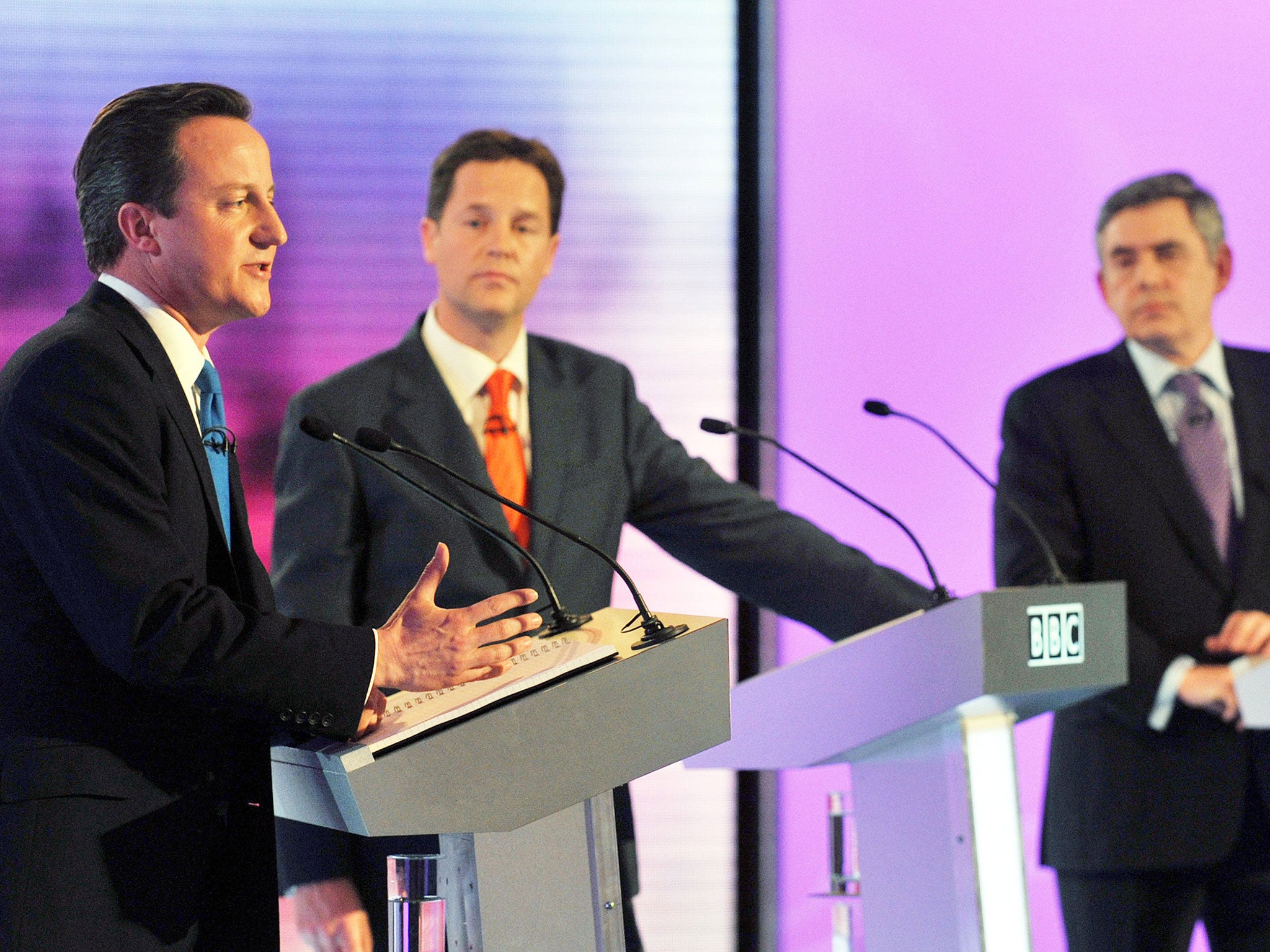

No one felt this more acutely than Gordon Brown in 2010, in what was our first ever British TV debate, a full half century after the Americans had pioneered the format. While David Cameron did appear on one debate in 2015, with all the other party leaders, the three 2010 Brown-Cameron-Nick Clegg shows remain the only ones the UK has had that come anywhere near the “classic” pattern.

In his memoirs, My Life, Our Times, Gordon Brown is characteristically grumpy and defensive, giving little space to what were, in all fairness, historic moments, the first proper prime ministerial television debates in British history. He explains his participation came down to money; he was basically attracted to the novelty because Labour was being so badly outspent by the Tories. As he puts it: “The debates created a more level playing field that disguised how limited our resources were, offering us free advertising at a time when we could not afford paid advertising. But, weighed down in the autumn and early spring by responding to the recession, I had not given enough attention to the downside of TV debates.

“They tend to favour opposition leaders, untainted by any record in office, as president Obama discovered in his first 2012 presidential debate against Mitt Romney. In Britain in 2010, they also gave the third party the same platform as the two main leaders. Both factors helped Nick Clegg, who did very well and was able to give the impression of offering a fresh start, as the new kid on the block.”

Clegg, comparatively little known before, became a sensation, and his fluent common-sense talk appealed to many, giving him a huge personal boost. Still, the brief “Cleggmania” that was unleashed, and the accidental catchphrase coined by Brown and David Cameron – “I agree with Nick” – failed to produce the kind of Liberal Democrat showing on polling day many had predicted.

The irony, if such it was, was that Clegg and his party nonetheless did well enough to see a hung parliament and the formation of a coalition government with the Tories, something that eventually resulted in the Lib Dems’ electoral destruction in 2015, and saw Clegg ejected from the House of Commons in 2017. Nick did not remain a “fresh face” for long after he put Brown and Cameron in the shade.

Indeed, Clegg’s next big set piece TV debate, over two episodes, was an entirely gratuitous grudge match with Nigel Farage about Europe in 2014; what we later came to call Brexit. It was a tetchy, ill-tempered encounter in which one time insurgent Clegg was now deputy prime minister and a firmly “establishment” figure, an ex- MEP and Brussels bureaucrat, ripe for taunting by Farage.

Some seven in 10 of the viewers judged the aggressive, cheeky, breezy Farage had the better of the bout, with Clegg sounding limp and complacent – an uncomfortable harbinger for the events of 2016. If Corbyn could push May into a similar corner and portray himself as the revolutionary he might enjoy some of the same success. Again, the incumbent is usually at a disadvantage over the insurgent, no matter how studious and well briefed the politician in power may be.

Who, for example, can forget how challenger Ronald Reagan, a ham actor of the first rank, somehow managed to hilariously – but charmingly – patronise the serous-minded and rational President Jimmy Carter in the 1980 campaign with the line “there you go again” – a “zinger”. Mr Corbyn, take note.

Limiting your downsides is the simplest thing – in theory – to accomplish, and there are some clear, transferable lessons May and Corbyn should take into any debates that take place – with the same rule applying to Boris Johnson, Vince Cable and others, if they ever get a look in.

The biggest lesson of the first major TV debate was that appearances matter. When then vice president Richard Nixon was running for the White House for the first time in 1960, and John F Kennedy was a mere senator from Massachusetts, Nixon was, by common consent, the more experienced – after eight years in office under President Eisenhower – the better prepared and the more skilled and combative in debate.

It was often said – though more recently the legend has been disputed – Nixon won his first debate with JFK among radio listeners, but lost with TV viewers because of his distractingly awful appearance. In the end the election was as tight on polling day as it had been almost throughout the campaign proper, so the damage Nixon suffered may not have been that serious in any case.

Nonetheless, even Nixon’s mother rang him after the show to ask if he was ill. He had, in fact, been dealing with a temperature of 103 degrees after he suffered a painful knee injury getting into a car – he was notoriously maladroit physically. His “optics” as we now call them, did him no favours.

According to Nixon’s later account: “When I arrived at the studio I was mentally alert but I was physically worn out and I looked it. Between illness and schedule, I was 10 pounds underweight. My collar was now a full size too large and it hung loosely around my neck.”

“Kennedy arrived a few minutes later looking tanned, rested and fit.

“My television adviser, Ted Rogers, recommended that I use television makeup but unwisely I refused, permitting only a little ‘beard stick’ on my perpetual five o’clock shadow.”

Nixon’s ordeal, like Brown’s 50 years later, also highlighted the dilemma of a serving or succeeding candidate for a governing party:

“An incumbent seldom agrees willingly to debate his challenger, and I knew that the debates would benefit Kennedy more than me by giving his views national exposure, which he needed more than I did. Further, he would have the tactical advantage of being on the offensive.

“As a member of Eisenhower’s administration, I would have to defend the administration’s record while trying to move the discussion to my own plans and programmes.

“But there was no way I could refuse to debate without having Kennedy and the media turn my refusal into a central campaign issue. The question we faced was not whether to debate, but how to arrange the debates so as to give Kennedy the least possible advantage.”

This they misjudged, running on domestic policy first, a relatively weak suit for Nixon. The most damaging blow, however, came not from JFK but from one of the journalists present.

He put to Nixon a quip Eisenhower had made when asked what major ideas Nixon had contributed as vice president: “If you give me a week I might think of one.” It was, said Nixon, “a question of no real substance” but, like his falling out of his shirt collar, it left an impression.

One could glimpse similar effects in many other US contests. In 1992 Bill Clinton found it easy to offer more folksy sympathy about the recession than the patrician George HW Bush – recently lauded as such a fine steersman, and rightly so. Bush also made the error of looking at his wristwatch while a member of the audience was asking a question – an innocent thing that made him look disrespectful.

Of course there is a question of natural ability and political and economic circumstances – it is tough to win any debate in the middle of a slump. Charismatic figures such as Kennedy in 1960, Reagan in 1976, Clinton in 1992, Obama in 2008 and – controversially – Trump in 2016 were always going to score over their less telegenic and more slow-witted/lazy/smug/boring rivals trying to cling to power – Nixon, Carter, Bush, John McCain and Hillary Clinton, respectively. By the same token, for incumbents – Reagan in 1984 against Walter Mondale and Clinton taking on the unhappily named Bob Dole in 1996 – a booming economy and a little wit and wisdom go a long way.

Watching the Hillary Clinton-Trump debates of 2016 reminds you just how much of a shock Trump was to the system. He dominated proceedings, talked over everybody and denied facts as “mainstream” fake news – all things we’ve grown used to. Yet he also has some energy, a little wit and, well, the charisma thing.

Hillary Clinton was on the defensive and tried to do what Reagan did to Carter – patronise him. She made Trump angry and, like the Incredible Hulk, he thrives on that. By contrast, she sounded arrogant and remote. While Trump actually had some policies – such as protectionism and pulling out of the Iran treaty and Nafta – all stupid but clear – Clinton just waffled. When she tried to hit Trump with the perfectly fair accusation that he refused to release his tax returns because he didn’t pay any federal tax, he chucked a zinger her way – “makes me smart”.

Sometimes incumbents – like Theresa May – have so little to lose they just gamble on a TV debate, hoping at the least to embarrass a challenger who tries to evade it. Like the Strictly/I’m a Celeb issues being raised, there are always plenty of ready excuses to hand. Here is biographer John Rentoul’s account of how Tony Blair – with a 20-point poll lead – sidestepped doomed John Major’s 1997 invitation to face him on TV – after Blair himself had first challenged Major. Whoops!

“Having challenged Major to a live televised debate ‘any place, any time’, Blair now made his excuses when the prime minister accepted – or rather, he asked Derry Irvine [to be Lord Chancellor in the New Labour government] to engage in a legalistic negotiation over terms designed to fail. ‘It was risk minimisation,’ said one adviser. ‘The whole election campaign would have become focused on it.’”

Nor were such shenanigans new. The first British prime ministerial debate almost happened in 1979. It didn’t, because of fears on both sides and thanks to Machiavellian manoeuvrings by both parties – but that didn’t stop Margaret Thatcher making it to the premiership, as always seemed likely.

James Callaghan, the Labour prime minister – like Brown 30 years on – felt he had little to lose but also had his doubts. For once though, Callaghan got the better of the leader of the opposition, Thatcher. Most people, including many of Thatcher’s advisers, felt her inexperience –at the time – would damage her, as Callaghan led her on personal poll ratings and was a more relaxed, warmer, more worldly sort.

Charles Moore, Thatcher’s official biographer, tells an extraordinary tale. “In 10 Downing Street, the decision [not to go ahead] was greeted with relief. Callaghan had felt he must be seen to be ready to debate, and Mrs Thatcher be seen to refuse, but he had been worried about it. Bernard Donoughue recorded; ‘He [Callaghan] is very pleased that Thatcher has declined to go on television against him – a relief to all of us, since I think she would have done well. She is much more effective than most of our people – or her advisers, apparently – seem to realise.’”

Thatcher was up for a scrap – as ever – but was persuaded not to take the gamble. Moore goes on: “If she had lost, she would have demonstrated straightforward incompetence. If she had won, that would have been a woman humiliating a man, and this would have been unsettling for many male voters. As Thorneycroft [Conservative Party chairman] put it to David Butler, ‘many men would have resented it. They would have said, “That’s my wife” and it wouldn’t have been a good thing.’”

Hard to fathom now, and, in any event, Mrs T never had much hesitation in humiliating men for the remaining years of her life. Few, at any rate, would see her slapping down Corbyn in such sexist terms today.

One of the oddest things about the proposed Corbyn-May debate was that they basically agree – though neither would much like to admit it. They are, in essence, both “soft Brexiteers”, and are thus ill placed to argue the merits of either Remain or hard Brexit – unlike, say, the Farage-Clegg event in 2014 in which the participants were miles apart.

YouTube is replete with elegant head-to-head debates between pro and anti-Europeans in the 1975 referendum campaign. To watch this old footage is to enter a world where the arguments of principle and economics are very much more precisely delineated than the kind of legalistic, party-political process-driven fights we’ve been enduring for most of the last three years or so.

Roy Jenkins kicking the economics around with Tony Benn; Ted Heath thrashing out the very meaning of sovereignty with Michael Foot; the urbane Jeremy Thorpe up against the fiery Barbara Castle in a proper debate, with a motion and votes, at the Oxford Union: all is clarity and sharp contrast. So Johnson and Cable are correct in expressing their concerns about the Corbyn-May show not being a real debate at all.

Beyond the possibility of a May-Corbyn Brexit debate, Sky News has been petitioning to see leaders’ debates in general elections – and presumably in referendums – made mandatory and run by a permanent commission just as they are in the US.

Many politicians are sympathetic, but there are real problems. The 2015 and 2017 British election debates – with as many as seven party leaders – suffered from overstaffing and lacked the gladiatorial drama of a simple double header. How this can be resolved in a multi-party parliamentary system is far from clear.

The final caution must come from the man who suffered most from the arrival of British TV debates, Gordon Brown. As he noted in his memoirs: “The once-a-week debates did suck the oxygen out of the campaign on the ground. In the weeks that the debates took place, on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday there was understandable media speculation about what would happen in the debate on Thursday, while on Friday, Saturday and Sunday the issue was the fallout.”

Would the great May-Corbyn Brexit debate have sucked “the oxygen out” of politics; or would it have helped us make our minds up in the inevitable second referendum?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments