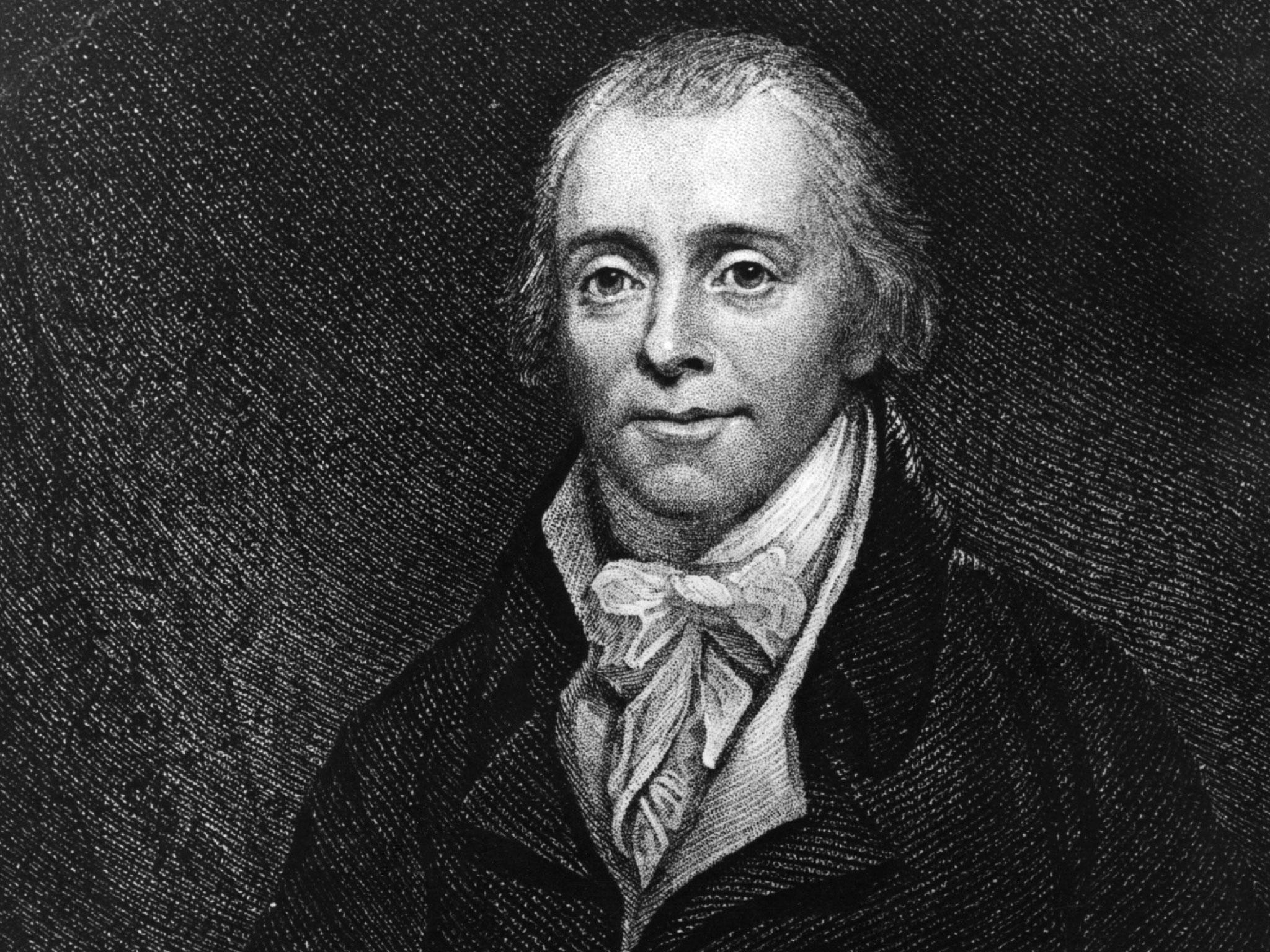

Spencer Perceval: The political assassination the world forgot

As the only British prime minister ever to be assassinated it seems remarkable that nobody has heard of Spencer Perceval. Now, 206 years after his killing, comedian and actor Nick Hall tells his story at the Edinburgh Fringe, drawing parallels with the present

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain is in turmoil. Social and political unrest spreads across the country, as old economic models clash with new technologies, and the spectre of global trade tariffs loom large. The country is locked in a bitter war with Europe, while in Downing Street an unpopular Tory prime minister, given the job after being judged a “safe pair of hands”, battles an intransigent parliament and back-stabbing from vainglorious colleagues who refuse to serve in the government. But this isn’t 2018. This is May 1812. And the prime minister is Spencer Perceval.

You probably saw that classic bit of misdirection coming, didn’t you? Look like you’re talking about Theresa May and then suddenly switch to a prime minister no one’s heard of. Alright then, back to 2018, at least for a bit.

This past month has seen another tumultuous episode in the British political sitcom, with the resignation of key cabinet ministers and the publishing of the long-awaited Brexit white paper pointing to a softer EU withdrawal than some had hoped. The prime minister is under renewed attack, the right-wing press and their supporters are up in arms, and yet again that poisonous word “traitor” is being wielded at anyone they find fault with. We are cursed to live in interesting times.

So why write about an obscure 19th-century prime minister? Because I believe our politics could learn a few lessons from the past. And that’s why I’m taking a show about Spencer Perceval to the Edinburgh Fringe this month.

To be honest, Spencer was a pretty mediocre prime minister. He never did anything particular noteworthy as leader, he was a classic late Regency period Conservative whose archaic world of rotten boroughs and landed gentry would be swept away by the Victorian age and the Great Reform Act.

Spencer’s rise to prime minister was unremarkably normal for the time, a “riches to riches” story, posh white guy easily becomes the most powerful person in the land. Like it or not, the story of Spencer Perceval is our Hamilton. But he does have one claim to fame. Spencer Perceval is the only British leader ever to be killed in office.

On 11 May 1812, just after five o’clock in the afternoon, Spencer was shot dead while walking through Central Lobby on his way to a debate in the House of Commons. The assailant immediately apologises and surrenders – a very British killing – but it is assumed that the revolution has begun. Who’s behind it? The luddites? The radicals? A shadowy conspiracy of wealthy businessmen? Within an hour a mob has descended upon parliament to cheer the killing, troops are deployed on the streets, and the Prince Regent has fled to Brighton.

This is Britain’s first great national newspaper story – a tabloid whodunnit. But that same evening the carriages carrying tomorrow’s editions are halted on their way out of London, as the government cracks down on the disorder. The revolution has been stopped in its tracks. The government breathes a sigh of relief.

Except there was no revolution to begin with. The “criminal mastermind” at the centre of it all was a failed businessman named Henry Bellingham, who blamed the prime minister for the £7,000 he had lost as the result of a debt dispute in Russia. There was no grand conspiracy, no higher motive, no grassy knoll, no second shooter, just an unhinged individual who believed he had been wronged and that the prime minister, as representative of the British state, should bear ultimate responsibility.

The trial was held three days later, with the jury taking a full eight minutes to find Bellingham guilty; and he was hanged the next day outside Newgate Prison. Spencer was buried in St Luke’s Church in Charlton, and with that the story of the two men faded from British history almost as quickly as it appeared.

Indeed, Spencer Perceval’s story has been more or less erased from British history. There’s no grand memorial to him. There’s a statue of him in Northampton, and they’ve turned four floor tiles the opposite way at the spot he fell in Parliament. And that’s about it. We know more about the murders of JFK or Abraham Lincoln than we do about our own prime minister. Why has Spencer’s story been so easily forgotten?

Maybe it’s because the British don’t really do political killings. Spencer is the only leader ever to be murdered in office. Haiti has two. America has four. Columbia has nine, which seems a bit greedy. The Americans are so brash about killing their leaders, even the site of their four assassinations are places of public entertainment; a theatre, a concert hall, a train station and a parade in Dallas. Us Brits on the other hand, we grumble and we moan but we put up with everything, the weather, delays to Northern Rail, Bake Off moving to Channel 4, endless decisions about building a third runway, and so on.

Except I don’t think that’s completely true. I don’t think the British just put up with everything. Looking back over the full sweep of British history, the idea of us as meek and mild doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny. The Peasants Revolt, the Chartist movement, the Peterloo massacre, the poll tax riots, Ukip leadership brawls (allegedly). The British have a long history of being up for a scrap when we need to.

I think there’s a discontent that constantly simmers away under the surface in Britain. We’re not comfortable with who we are in the world, as part of Europe, between different regions of the country, within our communities, our families and even within ourselves. And every now and then this discontent bubbles up and over. I think it did in 1812, I think it did again in 2016 with the Brexit referendum, and I think its still happening. And when that discontent goes unchecked and when public discourse is deliberately inflamed, that’s when people end up getting hurt. People like Spencer Perceval – and Jo Cox.

With his last words, John Bellingham hoped that the prime minister’s murder would “act a warning to future ministers to assist the applications and prayers of those who suffer by oppression”. These were poor words I think. Those on the political extremes use language as a weapon, to reaffirm their misguided belief that they are victims, a trampled minority, the real oppressed who suffer at the hands of a political class unwilling to listen to them. It validates their actions, no matter how heinous. And often it’s those in public office who bear the brunt of those actions.

Two years on from the tragic events surrounding the murder of Jo Cox, our politics and civil discourse feels just as polarised and shrill as ever. The recent revelation at trial of a plot to kill the MP for West Lancashire, Rosie Cooper, reminds us that the Pandora’s box of Brexit is very much wide open and no one can find the lid. And yet again in recent weeks we’ve seen the word “traitor” splayed out on newspaper front pages, fuelled by a vitriolic fury that your opponents are somehow enemies of the people for daring to have a different opinion to you. This constant shrieking language, exacerbated by the media and the internet, over chlorinated chicken and grooming gangs, does nothing to ease the situation and points to a dark and unpleasant future for Britain.

So what’s the solution? Well there doesn’t seem to be an easy one. Or maybe it is easy and that’s why it’s so hard to spot. It’s hiding in plain sight. What is needed is a renewed call for decency and level-headedness, for everyone to step away from the Twitter account and just calm down. To respect each other’s opinions rather than fling the words “traitor” and “racist” around like it’s confetti. For people to listen to each other a little more, and take the temperature down just a notch. It might not be the full solution but it’s a good place to start.

Spencer Perceval wasn’t a prime minister to echo down the ages, and he probably doesn’t deserve any grand memorial to his name. But if we could secure the “kinder, gentler” politics that some seem so happy to pay lip service to, then Spencer might just get a fitting legacy after all.

Nick Hall will be performing ‘Spencer’ at the Underbelly, Med Quad until 27 August, at 1.30pm daily (except for 13 August)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments