In search of the Sixties: Was the decade really as good as we think it was?

When asked what the Sixties were all about, most people reply: peace, love, happiness. Andy Martin begs to differ, arguing that the decade represented a whole lot more than just sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, and that no one has escaped its force and impact – even today

It was never just about the hair. Maybe it had a quite lot to do with hair though. When his grouchy boss grunted at him, one fine day, “And get your hair cut!” Richard Neville didn’t think twice, he was off. “I’ve just resigned,” he said later. “What am I going to do now?” The answer is, a hell of a lot.

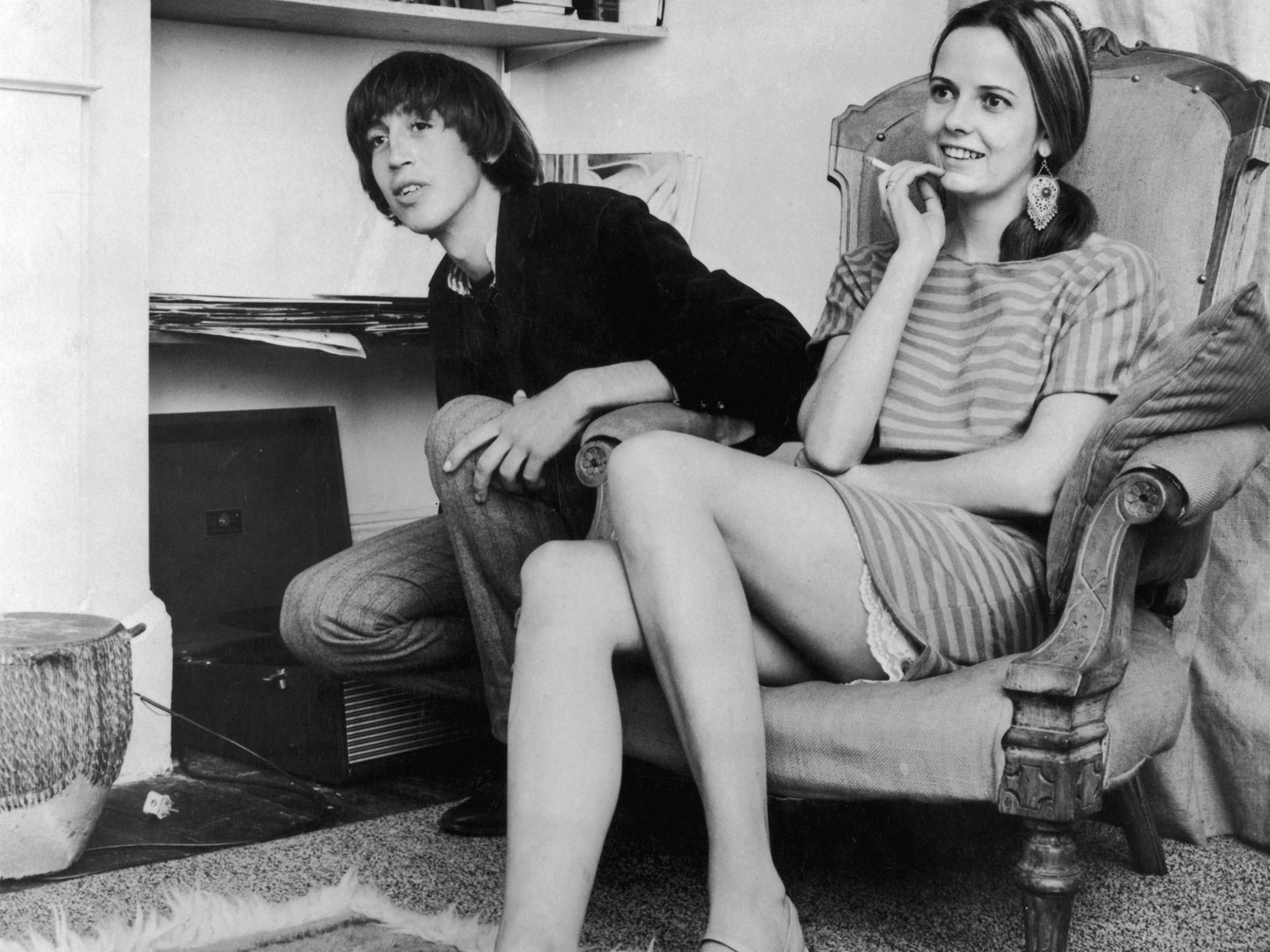

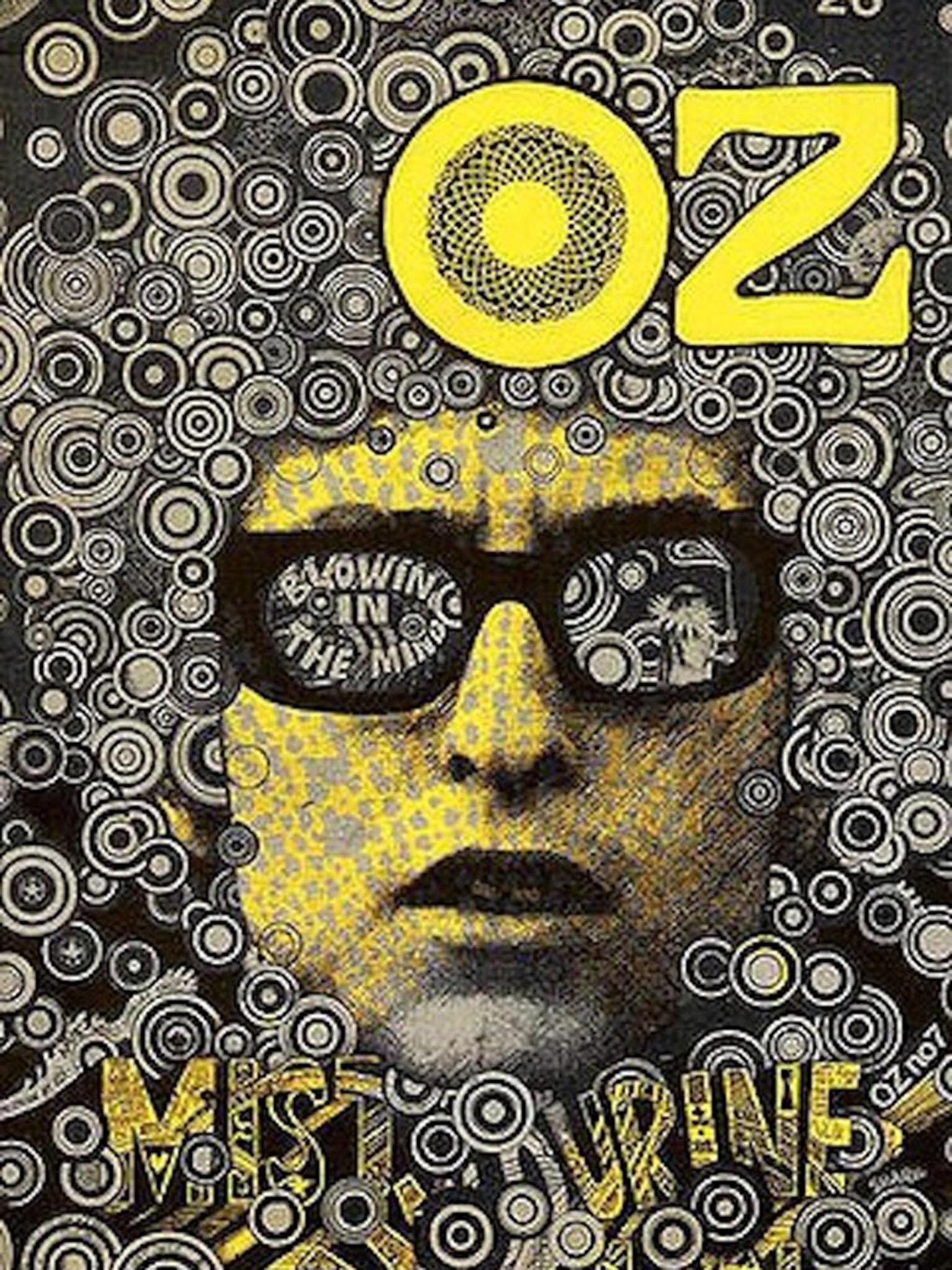

Richard Neville incarnated the spirit of Sixties London. Which was odd because he came from Australia. You could make a case that Australians were if not prime movers then enforcers or galvanisers of the Sixties cultural revolution (think of Germaine Greer, for example, whose The Female Eunuch summed up a lot of Sixties thinking, not to mention Clive James). But Neville was always my hero as a kid. He (together with Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis) put together the famous “Schoolkids” edition of Oz magazine, which was banned for obscenity (Rupert Bear, but well-hung).

Neville and his co-defendants were put on trial, found guilty, shoved in jail, then released on appeal, and they were defended and championed by John Mortimer (Rumpole) and the young Geoffrey Robertson. They were trailblazers, pioneers, subversives, liberators, and they did it with an abiding sense of humour.

Neville was a sort of John Lennon of publishing (Lennon even recorded “God Save Oz”). I read Oz in the 6th form common room with a mix of admiration, shock, and envy. I basically wanted to be Richard Neville. He was some rare combination of hip, hippy, and hipster. He was the embodiment of counterculture.

When I finally got to speak to him many years later, courtesy of the BBC, I was in London and he was in Byron Bay, New South Wales. It was a good line and there wasn’t even much delay and he sounded just the way he always had, an intellectual with wit and a lazy drawl. He reckoned that the most influential book of the Sixties was in fact Margaret Mead’s anthropological classic, Coming of Age in Samoa, published in 1928. That work (so eminently readable) is now largely dismissed as the product of a hoax, since the girls she had interviewed came out decades later and said they were largely spinning yarns, telling her what she wanted to hear, stories of how sexually liberated they were, at a young age, enabling her to re-tell the tales to the Northern hemisphere, hungry for Southern tropical eros – Henry Miller, but written by and for women, a kind of primer for Fifty Shades of Grey, Kama Sutra with palm trees and grass skirts. But we should also consider that these girls did actually tell those stories: whether they recorded real experiences or simply expressed desires, they were social facts.

***

“CHEER UP, CHILL OUT, YOU’RE ENTERING BYRON BAY”, said the road sign. I’d always wanted to track down Richard Neville, and ask him about his evolution. And I duly went to Byron Bay, in a spirit of pilgrimage and homage, knowing that Neville was already dead. He died last year, at the age of 74.

I discovered that there is a higher proportion of pony-tails (apparently known as “man-buns”) among the male population of this town than anywhere else on the planet (that I personally have come across). And the place has become insanely affluent. You could argue (as some did) that hipsters bear no resemblance to hippies. But it seems to me that all of us contain some reminiscence of the Sixties, we have absorbed, perhaps unaware, some part of that sacred epistemē.

Was the whole of the Sixties a hoax, like Coming of Age in Samoa? Some would say so. David Lister, writing in this newspaper some months ago, maintained that the values of the hippy movement, or the summer of love, were only ever espoused by a small handful of people who happened to hype it up rather a lot, rather as the Beach Boys gave out the idea that surfing came out of California.

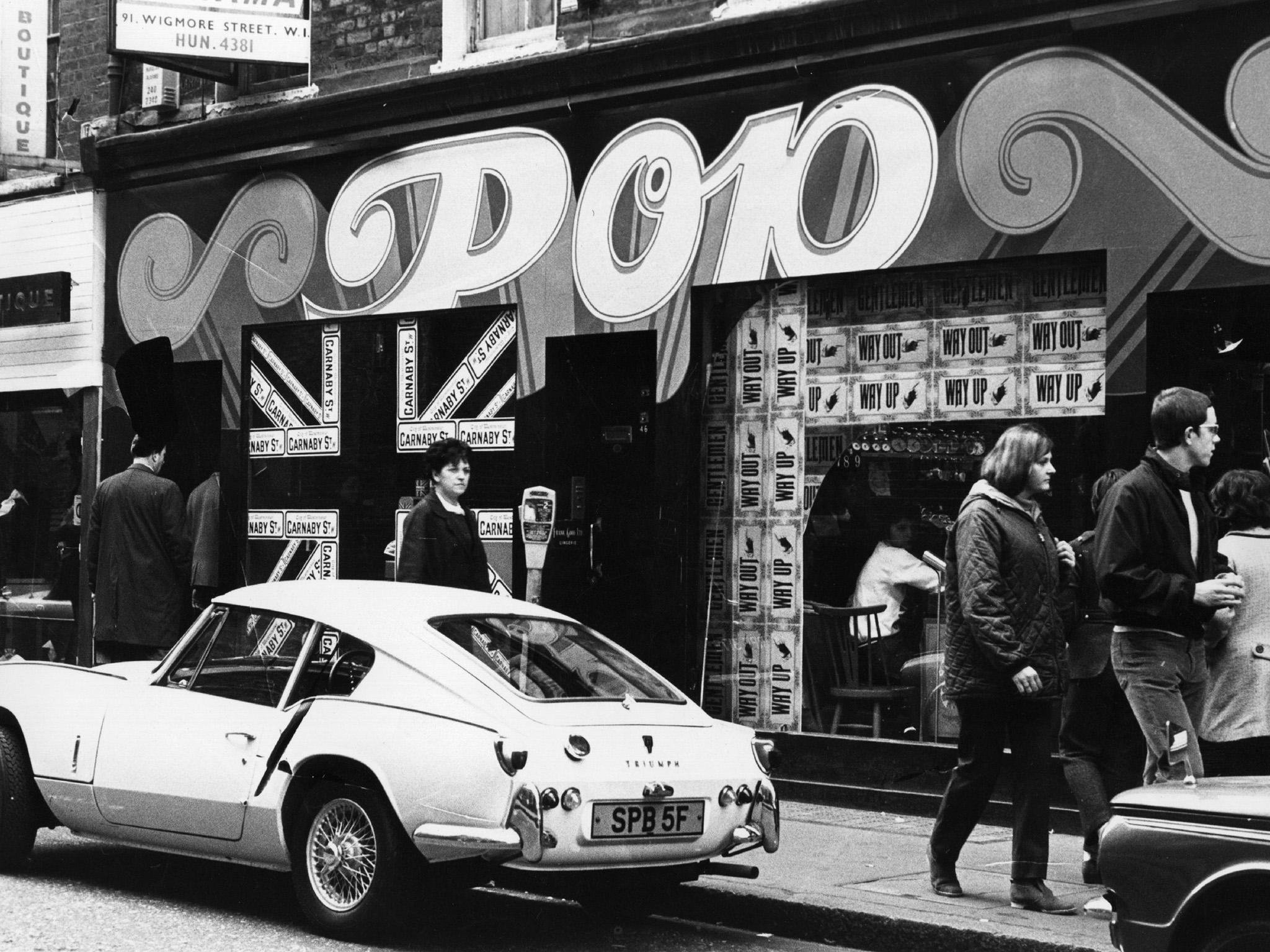

I want to argue almost the opposite and say that there is no escaping the Sixties, no matter who you are and where you are, even if only by opposition. It should also be admitted, of course that the very notion of the “Sixties” is clearly just an arbitrary chronological commodification, and at some level merely an exercise in salesmanship. The Sixties invented nothing, it was only ever recycling and reformulating (as the word “epistemē” and Richard Neville’s choice of book both suggest). And yet it did so with a force and vehemence that echoes and radiates down to us now.

If you ask anyone what the Sixties means to them (as I did) you’ll get an answer something like this: peace, love, and happiness (with small variations). I like the triadic structure of that answer, even if the content is a little hazy (drug-addled, you may say). It’s reminiscent of the French Revolution’s Freedom, Equality, Fraternity. Or the Holy Trinity. Or the Dialectic.

Others speak of the impact of acid from visiting Americans back in the day, all engaged in a Timothy-Leary-inspired mission to spread psychedelic hallucinations. But rather than go and have a quarter of a tab (I think that was the limit), I want to see if it’s possible to clarify some of the elements of the thinking that persist. Here are my three vectors of Sixties metaphysics. Feel free, in the spirit of the Sixties, to refute them if you will. I think they’re a slight improvement on sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. If the Sixties is anything, it’s a state (or states) of mind.

1. Non-anthropocentrism

I see this as a critique of humanism. It wasn’t that humanism had replaced religion sometime in the 18th or 19th century. Religion was only ever an offshoot of humanism. Because, we, humans, are such a big deal, naturally we need a sky god to keep an eye on us. And she/he/it is not only omniscient and omnipotent but loves us because we are so so interesting.

No, we are not. Humans, in the revisionary thinking of the Sixties, were merely a small part of something much more interesting that was going on, and could probably be dispensed with, ultimately. You can call this cosmic thinking. It certainly chimed in with the growth of cosmology and was probably accentuated by the Apollo Moon shots and those beautiful photographs of the planet in which you couldn’t even see any humans.

The Sixties paradigm was a natural extension of the Copernican Revolution in which the Earth was de-centred. This is the deconstruction of the species. I always liked the line of Albert Camus (one of the precursors who died at the beginning of the sixties): “I am the tree.” Under this heading one of the classic Sixties works was Jorge Luis Borges, “The Aleph”, a short story about a microcosm that brings out the interconnectedness of everything and boasts one of the longest sentences in literature.

2. Differentiation

At the same time as biped Earthlings were being assimilated and integrated into some larger phenomenon, Gaia or the Force, they were also being split up, disintegrated, fragmented. Henceforth, it was ok to be an alienated, anomic outsider. But you could join up with any number of largely imaginary groups.

This style of thinking fed into feminism and Black Power and perhaps even Islam, which can be seen less as a system of beliefs than an exercise in differentiation. Jacques Derrida’s theory of “différence” (or “différance”) exemplified the approach, since the thing you thought would have some kind of meaning (a “text”) turns out to be have many simultaneous conflicting meanings.

So too the human psyche of course (RD Laing’s The Divided Self is still an indispensable work). Queer and trans-gender philosophies owe something to the Sixties too. But I only want to mention one fairly extreme case I came across in Byron Bay, of one man who was slowly turning into one of his own sheep. Or at least identifying with them. And definitely starting to sound like one of them. I think differentiation says it is ok if you want to be a sheep. The classification of species is just another form of taxonomic delusion anyway. You are probably concerned about the potential, in this line of thought, for tribalism, or the herd mentality, which is why we need to take into account…

3 Transcendental hedonism

I was going to write “altruistic hedonism” but I thought the “transcendental” sounded more Sixties, reminiscent of TM (transcendental meditation). Byron Bay is a great surfing town and has largely been shaped by surfers over the last few decades. But we need to think of surfing as metaphor.

The experience is only ever an individual pleasure, albeit one that can be shared. The point about transcendental hedonism is the realisation that other beings also exist to experience pleasure (and therefore pain) and that the point of our existence is to try to increase the amount of pleasure in the universe at large, and thus (so far as possible) eradicate suffering (obviously vegetarianism and veganism come under this heading).

Rusty Miller – a surfing legend originally from California who benevolently put me up at his house – said, “I’m not looking for a better place” – talking of Byron Bay. But he also said: “I’m still a utopian dreamer”, by which I think he meant that he is a transcendental hedonist trying to build more pleasure into the world at large (which he does in part with his annual publication, “Rusty’s Byron Guide”).

But as Chris, a wiry sceptic, said of Byron Bay (and it’s true too of the Sixties): “They’ve marketed the arse off it. Turned it into some kind of theme park.” So I headed off into the hills, in Queensland, to the north, and tracked down a real Flower Child of old – as she describes herself – “Earth Mother”, living in a magical place in the middle of a rainforest, on the edge of a dormant volcano, in a house carved out of the landscape, fully organic and extremely wholesome, with a lot of wind chimes, where you awake to the laughter of kookaburras.

She expressed some measure of surprise that, after a life of high adventure, she was still alive. She also reckoned she had had somewhere between 300 and 3,000 previous lives. Which of course is hard to verify in any kind of precise way, although I believe her. But I particularly liked a line of hers which seemed to me to pull together rather neatly all of the strands of thought I sketched out above. “We are everything,” she said. “Or we’ve all been everything.”

I had a feeling Richard Neville would approve. He wasn’t an anti-capitalist dropout he was more an ethical (or democratic) capitalist. Apparently he used to go about giving lectures to large corporations telling them to behave better so that they would feel better. I think it’s not a bad idea.

Neville showed that the Sixties was not about being idle (“bums!” etc) or levitating. It was a critique of the Puritan work ethic concept of Weber’s, which said that a belief in a certain narrow branch of Christianity led to the rise of capitalism.

Richard Neville and the Sixties generally were all about erasing the divide between being and doing: it was possible to be productive (such is the ethic of companies like Apple and Google now, a form of virtual surfing) and still be on a high – enjoy a “peak experience”, without resorting to LSD. At the heart of Sixties thinking remains a principle of creativity, not passivity. I want to put forward a radical interpretation of what we might call New Sixties Thinking, which perhaps a lot of Old Sixties people might want to disagree with: “Work is (or should be) fun.”

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks