Legendary journalist Seymour Hersh on novichok, Russian links to Donald Trump and 9/11

In a rare interview, veteran investigative journalist Seymour Hersh talks about his illustrious career and how he believes the official versions of some the biggest news stories of our time just don’t add up

I’m about to interview the 81-year-old doyen of investigative journalism Seymour Hersh. Sy Hersh – as he is affectionately known by those close to him – was once described by the Financial Times as “the last great American reporter”. Hersh has brought out his memoir Reporter covering the span of his career as one of the iconoclastic journalists of the 20th century – the man who exposed the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and who later brought the abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in the Iraq War to the attention of the world.

Hersh has recently been in London for a talk at the Centre for Investigative Journalism at Goldsmiths. It makes for a raucously entertaining two hours in which he holds court on everything from Vietnam and the war on terror to the Skripal novichok poisoning, Trump and the alleged Russian hacking of the election. Octogenarian Hersh is already back in Washington by the time we speak on the phone.

He has been ploughing his furrow since long before I was born. It is hard not to be in awe of the man. You could say that I am just a tad nervous. His street-wise Chicago demeanour means that he can be a tough interviewee. Luckily for me, Hersh is in a good mood – he is extremely jovial and spends most of the interview chuckling as he regales me with tales of his illustrious career.

During the 1970s, Hersh covered Watergate for The New York Times and revealed the clandestine bombing of Cambodia. And in what he describes as “the big one”, he also uncovered the CIA’s large-scale domestic wiretapping programme surveilling the anti-war movement and other dissident groups (in contravention of its charter not to spy on US citizens). He has consistently been a thorn in the side of the establishment.

Along with Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, Hersh is perhaps responsible for the glamorous image of the investigative reporter – shirt sleeves rolled up making calls for the latest scoop or meeting anonymous sources on deep background in undisclosed locations. The reality is undoubtedly far less glamorous and largely consists of hard graft. As Hersh relates in his memoir, he inherited his industrious work ethic from his father and never knew any other way of living.

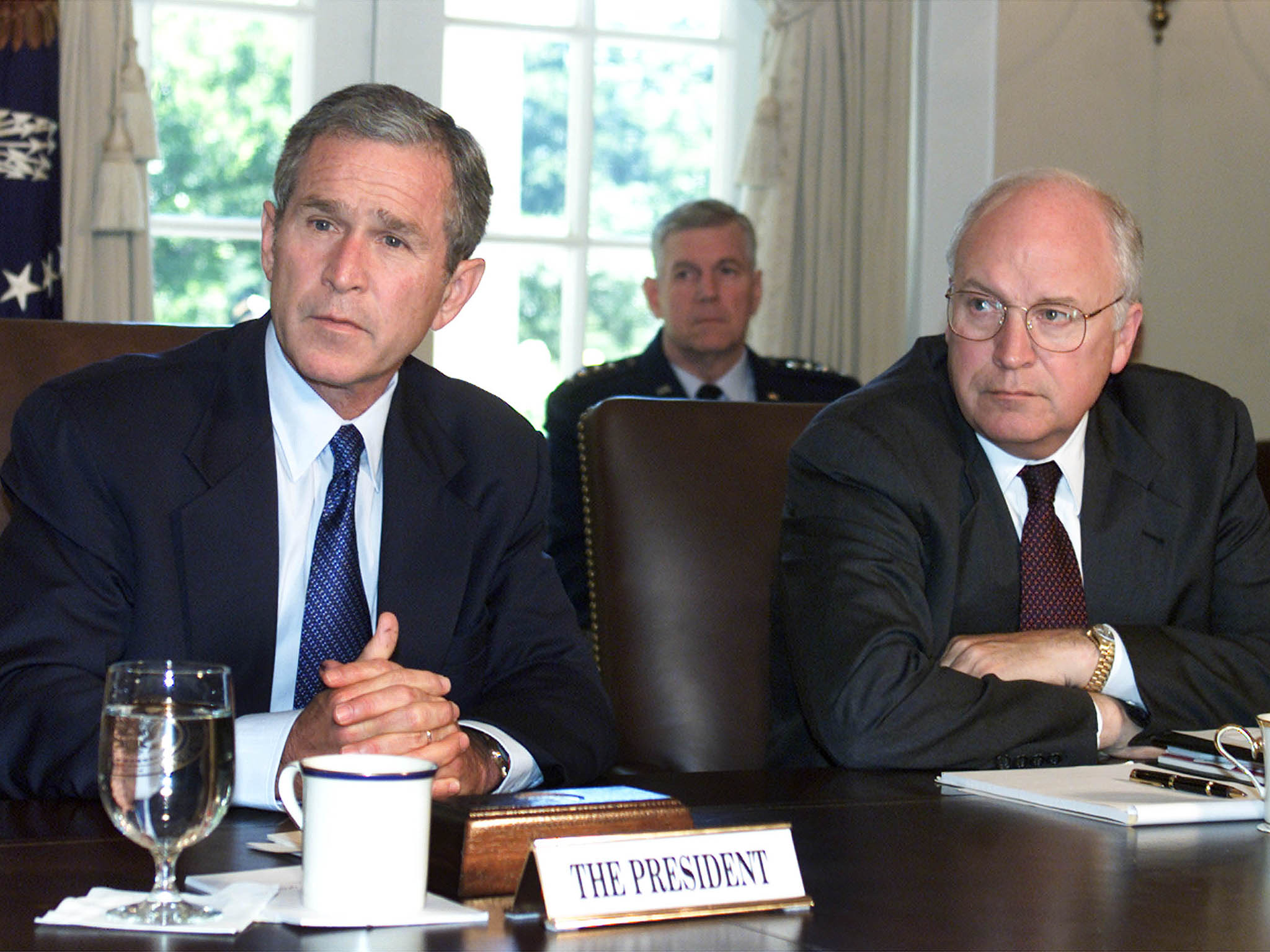

The story of how Hersh came to write his memoir after swearing never to write about family matters is typically Hershian. He was working on a book on Bush vice president Dick Cheney when the backlash against whistleblowers meant that he could no longer protect his sources. As a result, he offered to sell his pied-à-terre in order to pay back the generous advance but Sonny Mehta – the editor-in-chief of Alfred Knopf – persuaded him to write an autobiographical account.

Reporter reads like the cross-pollination of Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March and All the President’s Men. Hersh grew up in the Chicago suburbs and was forced to take over the running of the family laundry business in his teens after his father died of lung cancer. He did not shine at school and was not destined for an intellectual life, seemingly stumbling into a career as a newspaper man.

Serendipity would have it that he answered the phone the morning after an all-night poker game in which he lost all of his money. The call was from City News. He happened to be staying at his old apartment that night having forgotten to inform his future employers that he had changed address. And so began inauspiciously one of the most remarkable careers in journalism. If it was not for Hersh’s penchant for all-night poker games, we may never have known about all manner of deep state malfeasance.

In fact, he struggled for many years to find secure employment. The My Lai stories changed everything. Hersh’s writing has been seared into history. From the mother of one of the soldiers telling him, “I sent them a good boy, and they made him a murderer.” Or one of the other soldiers, who begins his account by stating plainly, “It was a Nazi-type thing.”

The descriptions of babies being tossed up in the air and bayoneted or of soldiers arriving for their first tour to find a military jeep speeding by with human ears sewn to its dashboard are bone-chilling. The My Lai story brought home the brutality, depravity and monstrosity of the American war machine fuelling the anti-war movement.

Yet even with a Pulitzer Prize in hand, he still could not land his dream job at The New York Times. His cantankerous tendencies may not have helped, having hung up twice on executive editor Abe Rosenthal.

Hersh is honest enough to admit that today he might not have made it. He worked during the heyday of American journalism – when he was paid handsomely for exposes and when media outlets had the financial muscle to fund serious writing. When he covered the Paris Peace Accords for The Times, he was put up at the world famous five-star deluxe Hotel de Crillon.

The day after 9/11 we should have gone to Russia. We did the one thing that George Kennan warned us never to do – to expand NATO too far

It is not long before we discuss contemporaneous events including the alleged Russian hacking of the US presidential election. Hersh has vociferously strong opinions on the subject and smells a rat. He states that there is “a great deal of animosity towards Russia. All of that stuff about Russia hacking the election appears to be preposterous.” He has been researching the subject but is not ready to go public… yet.

Hersh quips that the last time he heard the US defence establishment have high confidence, it was regarding weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. He points out that the NSA only has moderate confidence in Russian hacking. It is a point that has been made before; there has been no national intelligence estimate in which all 17 US intelligence agencies would have to sign off. “When the intel community wants to say something they say it… High confidence effectively means that they don’t know.”

Hersh is also on the record as stating that the official version of the Skripal poisoning does not stand up to scrutiny. He tells me: “The story of novichok poisoning has not held up very well. He [Skripal] was most likely talking to British intelligence services about Russian organised crime.” The unfortunate turn of events with the contamination of other victims is suggestive, according to Hersh, of organised crime elements rather than state-sponsored actions – though this files in the face of the UK government's position.

Hersh modestly points out that these are just his opinions. Opinions or not, he is scathing on Obama – “a trimmer … articulate [but] … far from a radical … a middleman”. During his Goldsmiths talk, he remarks that liberal critics underestimate Trump at their peril.

He ends the Goldsmiths talk with an anecdote about having lunch with his sources in the wake of 9/11. He vents his anger at the agencies for not sharing information. One of his CIA sources fires back: “Sy you still don’t get it after all these years – the FBI catches bank robbers, the CIA robs banks.” It is a delicious, if cryptic aphorism.

I ask about how the war in Syria has been a divisive issue for the left. Hersh wrote a series of controversial long reads for the London Review of Books insinuating that the Assad government might not have been responsible for the chemical weapons attacks. He had been writing for decades at The New Yorker, which turned down these pieces leading to a falling out.

In “The Red Line and the Rat Line”, Hersh argued that both sides had access to chemical weapons. He even went one better and postulated that the rebels or even the Erdogan Turkish government may have carried out a false flag attack to twist Obama’s arm into escalating US involvement as this would have crossed his self-imposed red line.

Hersh also highlighted that a “rat line” of arms had been set up between Libya and Syria by the CIA with the involvement of MI6 using front companies. This was designed to supply the Syrian rebels including jihadi groups in their efforts to oust Assad – startling revelation considering that the US is prosecuting a war on terror and intending to neutralise Islamic State.

Hersh deals with criticisms of the Assad regime one by one. He brusquely tells me: “If Assad loses he will be hanging from a lamp-post” with his wife and children alongside him. He elaborates that, “Heinous things happen in war”, recounting the Allies’ firebombing of Japanese and German cities as well as the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War. His point is that all sides commit war crimes.

In fact, he tells me that the US has also deployed barrel bombs. One could obviously add much more to this catalogue including the use of Agent Orange and other chemicals in Vietnam as well as the use of white phosphorus and depleted uranium in Iraq. “Where is the moral equivalence?” Hersh asks. All of which reminds me of gung-ho US General Curtis LeMay’s infamous statement that if he had lost the Second World War, he would have been tried for war crimes.

Hersh tells me that this is “as close to a just war” because Assad is fighting to prevent an Islamist takeover and the imposition of Sharia law. Critics will rebut that this is a reductively simplistic analysis of the situation with moderate forces on the ground. And surely there is no doubt that the Baathist Assad regime is a brutal dictatorship? Hersh casually drops into the conversation that he met Assad five or six times before the war – a reminder of the astonishing life that he has led meeting the good, the bad and the ugly.

We move on to talk about the covert funding and arming of Islamists going back to the Mujahideen during the Soviet war in Afghanistan. This was overseen by western intelligence agencies as well as the Saudis and Pakistanis. Hersh recounts how Jimmy Carter’s fiercely anti-communist national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski planned to lure the Russians into their own Vietnam – a quagmire that would catalyse the downfall of the Soviet Union.

During the Goldsmiths event, Hersh vaguely alludes to a funding programme that he has come across but does not divulge further. Most well informed people are aware of the origins of this story. Very few realise that this has been a wide-scale secretive programme, which extended into the former Soviet states as well as across the Middle East and Africa up until the present day. It has been designed to facilitate geopolitical aims presumably on the basis that the ends justify the means. I mention 1950s British intelligence documents with the stated aim of neutralising Arab socialism and nationalism. “Imperialism is imperialism,” Hersh retorts.

In another article, “Military to Military”, Hersh disclosed top secret high-level communications between the military powers engaged in the Syrian theatre. When the US joint chiefs of staff bypassed Obama in order to pass on important intelligence in the fight against Islamic State, an Assad friend responded that they should bring him the head of Bandar to demonstrate good faith. Prince Bandar bin Sultan was the former Saudi ambassador to the US and the director general of the Saudi intelligence agency GID. According to reports in The Wall Street Journal, he acted as the lynchpin in arming the jihadis fighting Assad. Bandar remains close to the Bush clan. Unsurprisingly, the Americans declined the offer.

I enquire about the role of Bandar in various deep events including acting as the go-between in the CIA arming of the Mujahideen in Afghanistan, the BAE Al Yamamah arms deal notorious for massive bribes and kickbacks as well as Iran Contra. He even pops up in multiple instances in the 9/11 report, including in relation to payments from his wife Princess Haifa’s bank account being wired to a contact of two of the hijackers. Hersh does not dwell on this but believes that the Saudi crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman may well turn out to be worse than Bandar.

Sensing that Hersh may still be preoccupied with the Bush era having abandoned his Cheney book, I ask about an article he wrote in 2007 in The New Yorker entitled “The Redirection”. He tells me it is “amazing how many times that story has been reprinted”. I ask about his argument that US policy was designed to neutralise the Shia sphere extending from Iran to Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon and hence redraw the Sykes-Picot boundaries for the 21st century.

The guy was living in a cave. He really didn’t know much English. He was pretty bright and he had a lot of hatred for the US. We respond by attacking the Taliban. Eighteen years later… How’s it going guys?

He goes on to say that Bush and Cheney “had it in for Iran”, although he denies the idea that Iran was heavily involved in Iraq: “They were providing intel, collecting intel … The US did many cross-border hunts to kill ops [with] much more aggression than Iran”.

He believes that the Trump administration has no memory of this approach. I’m sure though that the military-industrial complex has a longer memory. Hersh was at a meeting in Jordan at some point in the last decade, where he was informed that, “you guys have no idea what you are starting” referring to the bloody sectarianism that was about to be unleashed in Iraq.

I press him on the RAND and Stratfor reports including one authored by Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz in which they envisage deliberate ethno-sectarian partitioning of Iraq. Hersh ruefully states that: “The day after 9/11 we should have gone to Russia. We did the one thing that George Kennan warned us never to do – to expand NATO too far.”

We end up ruminating about 9/11, perhaps because it is another narrative ripe for deconstruction by sceptics. Polling shows that a significant proportion of the American public believes there is more to the truth. These doubts have been reinforced by the declassification of the suppressed 28 pages of the 9/11 commission report last year undermining the version that a group of terrorists acting independently managed to pull off the attacks. The implication is that they may well have been state-sponsored with the Saudis potentially involved.

Hersh tells me: “I don’t necessarily buy the story that Bin Laden was responsible for 9/11. We really don’t have an ending to the story. I’ve known people in the [intelligence] community. We don’t know anything empirical about who did what”. He continues: “The guy was living in a cave. He really didn’t know much English. He was pretty bright and he had a lot of hatred for the US. We respond by attacking the Taliban. Eighteen years later… How’s it going guys?”

The concept of perpetual war is not exactly unintentional. The Truman doctrine hinged on this. His successor Eisenhower coined the term “military-industrial complex”. In 2015, giant defence contractor Lockheed Martin’s CEO stated that the more instability in Asia Pacific and the Middle East the better for their profit margins. In other words, war is good for business.

We also cover his recent work on the purported mythology surrounding Bin Laden’s death in his previous book The Killing of Osama Bin Laden. Hersh tells me: “He escaped into Tora Bora. My guess is the Pakistani intelligence service picked him up pretty early. It was likely that he was in Abbottabad [the military garrison town where he was eventually killed] for 5-6 years according to ISI [Pakistani intelligence] defectors.” At the same time, he states that the Americans did not know. “Nobody knows … Someone walked in and told us,” he says, referring to the Pakistani defector who picked up most of the bounty worth £25m.

Hersh has taken a lot of flak over recent years regarding his articles on Syria and Bin Laden. He has been accused of being an apologist for Assad and the Russians, though he maintains he is seeking out the truth.

Critics have also argued that Hersh is a conspiracy theorist, though notably in his John F Kennedy biography The Dark Side of Camelot, he writes that Oswald was the probable lone assassin. Several years ago, I grilled Hersh on this and he responded that he simply could not find anything more on Oswald whilst researching the book. It seems that this position is adopted by others on the left too such as Noam Chomsky, who views JFK as a liberal war hawk rather than a threat to the establishment.

I have to say I’m perplexed to say the least that a man who has spent his entire career dealing with covert action and spies buys the official version report hook, line and sinker. In Reporter, he warmly relates his dealings with Hollywood director Oliver Stone in the late Eighties. However, when Stone begins to expand on his thesis that Kennedy was assassinated by a CIA conspiracy in what would eventually become his tour de force magnum opus JFK, Hersh is completely dismissive, telling Stone that the idea is preposterous – to which Stone replies that he always knew Hersh was a CIA agent and walks off.

Hersh shows no signs of slowing down. He clearly has plenty of work in progress with the tantalising prospect of reporting on the alleged hacking of the Democratic National Committee and the US election. And who knows? Maybe that Cheney book will eventually see the light of day. It looks like there might still be a chapter or two to add to his memoir after all.

Youssef El-Gingihy’s new, updated and expanded edition of ‘How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps’, published by Zero Books, will be out later this summer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks