How a public map helped an archaeologist to discover ancient Mayan ruins

Takeshi Inomata used a lidar map, which uses light detection and ranging, to find 27 previously unknown Maya ceremonial sites. Zach Zorich reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Until recently, archaeology was limited by what a researcher could see while standing on the ground. But light detection and ranging, or lidar, technology has transformed the field, providing a way to scan entire regions for archaeological sites.

With an array of airborne lasers, researchers can peer down through dense forest canopies or pick out the shapes of ancient buildings to discover and map ancient sites across thousands of square miles. A process that once required decades-long mapping expeditions, and slogging through jungles with surveying equipment, can now be done in a matter of days from the relative comfort of an aeroplane.

But lidar maps are expensive. Takeshi Inomata, an archaeologist at the University of Arizona, recently spent $62,000 (£48,000) on a map that covered 35 square miles, and even that price was a discount. So he was thrilled last year when he made a major discovery using a lidar map he had found free online, in the public domain.

The map, published in 2011 by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography, covered 4,440 square miles in the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas. It was made as part of the institute’s mission to create accurate maps to be used by businesses and researchers.

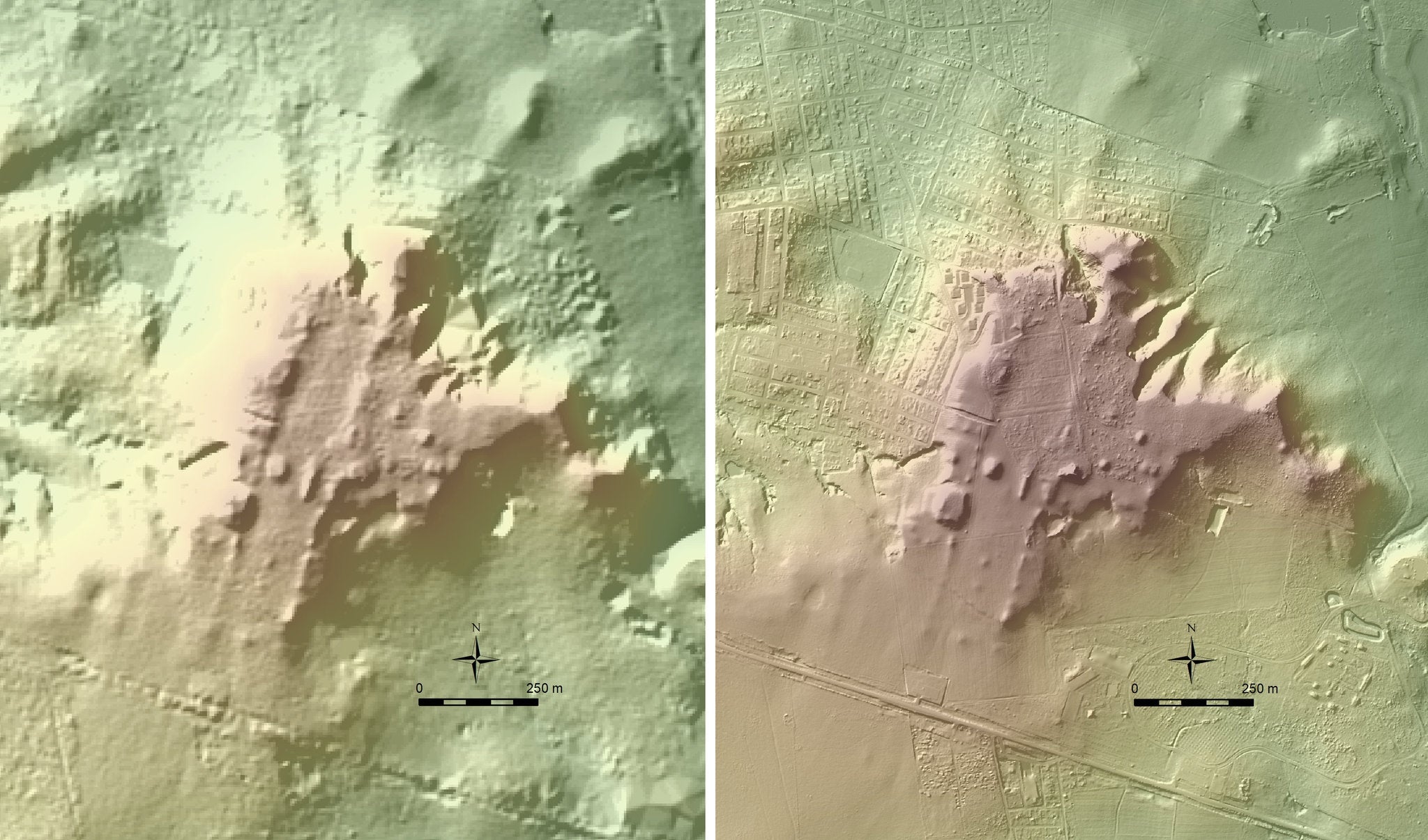

Inomata learned about the map from Rodrigo Liendo, an archaeologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The map’s resolution was low. But the outlines of countless archaeological sites stood out to Inomata. So far, he has used it to identify the ruins of 27 previously unknown Maya ceremonial centres that have a type of construction that archaeologists had never seen before. These sites may hold insights into the origins of Maya civilisation.

“We can see a much better picture of the entire society,” Inomata says. His findings have not yet been peer-reviewed, but Inomata has presented his work at four conferences during the past year. “The stuff he is finding is crucial for our understanding of how Maya civilization developed,” says Arlen Chase, an archaeologist at Pomona College, who did not contribute to Inomata’s work.

Chase was among the early adopters of lidar. In 2009 he used it to map Caracol, a Maya city in Belize, where he and his wife Diane Chase, an archaeologist at Claremont Graduate University, have worked for 35 years. Their son Adrian, a PhD candidate at Arizona State University, is using lidar to compare the square footage of more than 4,000 homes in Caracol as a way to infer social inequality. (Presumably then, as now, wealthier residents had larger homes.) Such an analysis would have been all but impossible before lidar.

The Maya civilisation arose between 1000BC and 400BC. When Inomata first began studying the Maya as a graduate student in the 1980s, his professors were mainly interested in the Classic Period, between AD250 and AD900, when the Maya were at their political and economic peak. Inomata was more interested in how Maya culture began, and the artefacts that could answer his questions were buried even deeper underground.

Years passed before he had enough grant money, and a sufficiently secure academic appointment, to start that project. Finally, in 2005, he and his wife, Daniela Triadan, an anthropologist at the University of Arizona, began excavating the ancient city of Ceibal in the Peten rainforest in Guatemala, where they discovered some of the earliest known Maya buildings. The city’s ceremonial centre dates to 950BC, but Ceibal didn’t have permanent housing until 200 years later.

Triadan and Inomata believe that the earliest Maya were probably living a migratory lifestyle, going to Ceibal only for religious purposes. How they transitioned to settling down in large cities and what role the Olmec civilisation, which preceded the Maya, played in the founding of the Maya civilisation are the big questions that Inomata and Triadan are seeking to answer. Olmec-style artefacts were found among the earliest buildings at Ceibal, indicating that the Maya civilisation was influenced by the Olmec from the beginning. “The relationship between the Maya and Olmec gets at the origins of Mesoamerican civilization overall,” Inomata says.

The Olmec and the Maya civilisations differed in important ways. Power in the Olmec state was concentrated in the hands of a single ruler; the famous Olmec stone heads may have been portraits of their kings. Less is known about the earliest Maya rulers, because they didn’t glorify their kings with monuments until much later. The Maya and Olmec also developed unique languages and their own architectural and artistic styles.

After discovering some of the earliest known Maya buildings at Ceibal, the next step for understanding how the Olmec influenced the beginnings of Maya culture was to study the area between Ceibal and the centers of the Olmec culture. The Mexican government’s publicly available lidar map made Inomata’s job surprisingly easy.

The 27 sites Inomata identified on the map have a type of ceremonial construction that he and his colleagues had never seen before – rectangular platforms that are low to the ground but extremely large, some as long as two-thirds of a mile. “If you walk on it, you don’t realise it,” Inomata says of the platforms. “It’s so big it just looks like a part of the natural landscape.” The similarities between these sites and the early buildings they found at Ceibal led them to believe they both date to sometime between 1000BC and 700BC.

If you walk on it, you don’t realise it, it’s so big it just looks like a part of the natural landscape

“The amount of labour is staggering,” Triadan says. She describes a scene of hundreds of people coming together from across the region to dig and carry baskets of dirt to build the platforms. “We may have relatively mobile populations who are putting a lot of effort into these massive communal enterprises,” she adds.

Inomata and Triadan are now leading excavations at the largest ceremonial centre they found on the free lidar map, a site they have named Aguada Fenix, where they hope to learn more about the earliest rituals of the ancient Maya.

Inomata’s work with publicly available lidar maps has also inspired Charles Golden, an anthropology professor at Brandeis University, to look at lidar maps that Nasa made as part of a survey of forest cover in Mexico. The data helped him to identify a series of ancient settlements near the Usumacinta river, which forms part of the border between Mexico and Guatemala. Golden has used a drone-based lidar system to get more detailed images of these sites. Drones can’t cover as much territory as planes, but they can be easily redirected if something interesting comes to light.

While lidar technology is giving archaeologists new ways to analyse the ancient world, the change in perspective has been shocking for some researchers. Marcello Canuto, director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University, was the lead author of a lidar survey that covered 800 square miles of the Peten rainforest in Guatemala. He is also the director of an excavation at the Maya city of La Corona. Seeing the edges of the city as well as buildings between cities and the roads that connected them was shocking to him. “The word that all of us used when we started looking at the lidar was ‘humbling,’” he says. “It humbled all of us in showing us what we had missed.”

The word that all of us used when we started looking at the lidar was ‘humbling’. It humbled all of us in showing us what we had missed

Inomata agrees. Even in areas where they were busy excavating, he says: “lidar was showing us things we didn’t notice.” This included broad causeways and agricultural terraces, which are difficult to see in an excavation. “We can see a much better picture of the entire society,” he adds.

Viewing the archaeology of an entire region, in detail, will allow archaeologists to answer bigger-picture questions, such as the ones that Inomata has about the interactions the Maya had with the Olmec at the beginning of their civilisation.

The lidar map that Inomata used to make his discovery is continually being expanded by the Mexican government to cover new areas. Other countries, including the United States, have similar mapping programmes underway. “The future pattern,” Inomata says, “will be that everything will be covered by lidar, like topographic maps today.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments