For survivors of school shootings in America, life is never the same

Every day, pupils in the US hide in closets as killers pace the halls. Sometimes, it’s a drill. Sometimes, it’s not. The death toll for school shootings is high, but thousands more survive

Thirteen at Columbine. Twenty-six at Sandy Hook. Seventeen at Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

Over the past two decades, a handful of massacres that have come to define school shootings in this country are almost always remembered for the students and educators slain. Death tolls are repeated so often that the numbers and places become permanently linked.

What those figures fail to capture, though, is the collateral damage of this uniquely American crisis. Beginning with Columbine in 1999, more than 187,000 students attending at least 193 primary or secondary schools have experienced a shooting on campus during school hours, according to a year-long Washington Post analysis. This means that the number of children who have been shaken by gunfire in the places they go to learn exceeds the population of Eugene, Oregon, or Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Many are never the same.

School shootings remain extremely rare, representing a tiny fraction of the gun violence epidemic that, on average, leaves a child bleeding or dead every hour in the United States. While few of those incidents happen on campuses, the ones that do have spread fear across the country, changing the culture of education and how kids grow up.

Every day, threats send classrooms into lockdowns that can frighten students, even when they turn out to be false alarms. Thousands of schools conduct active-shooter drills in which children as young as four hide in darkened closets and bathrooms from imaginary murderers.

“It’s no longer the default that going to school is going to make you feel safe,” says Bruce D Perry, a psychiatrist and one of the country’s leading experts on childhood trauma. “Even kids who come from middle-class and upper-middle-class communities literally don’t feel safe in schools.”

Samantha Haviland understands the waves of fear created by the attacks as well as anyone.

At 16, she survived the carnage at Columbine High, a seminal moment in the evolution of modern school shootings. Now 35, she is the director of counselling for Denver’s public school system and has spent almost her entire professional life treating traumatised kids. Yet, she’s never fully escaped the effects of what happened to her on that morning in Littleton, colourado. The nightmares, always of being chased, lingered for years. Even now, the images of children walking out of schools with their hands up is too much for her to bear.

On Saturday, some of Haviland’s students, born in the years after Columbine, will participate in the Denver March For Our Lives to protest school gun violence. In Washington, students from Parkland, Florida – still grieving the friends and classmates they lost last month – will lead a rally of as many as 500,000 people in the nation’s capital.

“They were born and raised in a society where mass shootings are a thing,” she said, recalling how much her community and schoolmates blamed themselves for the inexplicable attack by Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. “These students are saying: ‘No, no – these things are happening because you all can’t figure it out.’ They’re angry, and I think that anger is appropriate. And I hope they don’t let us get away with it.”

Mass shootings at predominantly white schools draw the most attention from journalists and lawmakers, but the report found that children of colour are far more likely to experience campus gun violence – nearly twice as much for Hispanic students and three times for black students.

In analysing school shootings, we defined them far more narrowly than others who have compiled data over the past few years. Everytown for Gun Safety’s tally, for example, contains episodes of gunfire even on late nights and weekends, when no students or staff were present. The Gun Violence Archive disregards those events but does include others that occur at extracurricular activities, such as football games and dances.

We only counted incidents that happened immediately before, during or just after classes to pinpoint the number of students who were present and affected at the time. Shootings at after-hours events, accidental discharges that caused no injuries, and suicides that occurred privately or didn’t pose a threat to other children were excluded, though many of these can be deeply disturbing. Gunfire at colleges and universities, which affect young adults rather than children, also were excluded.

In total, our report found an average of 10 school shootings per year since Columbine, with a low of five in 2002 and a high of 15 in 2014. Less than three months into 2018, there have been 11 shootings, already making this year among the worst on record.

At least 129 kids, educators, staff and family members have been killed in assaults during school hours, and another 255 have been injured. But the analysis went much deeper than that, exploring the types of attacks, the impact on minority students, the role of armed resource officers, the weapons used and where they were obtained, and the characteristics of shooters.

Schools in at least 36 states and the District of Columbia have experienced a shooting, according to our count. They happen in big cities and small towns, in affluent suburbs and rural communities. The precise circumstances in each incident differs, but what all of them have in common is the profound damage they leave behind.

Gangs and grudges

The day had just begun at the high school in Memphis when a sophomore walked up to a senior during gym class and pointed a .22-caliber pistol at him. In a room packed with 75 students on that morning in 2008, Corneilous Cheers, 17, opened fire, striking his schoolmate in the leg, the groin and the head. As his rival bled on the floor, Cheers turned to their gym teacher at Mitchell High and handed him the gun.

“It’s over now,” the teen said.

The term “school shooting” often conjures a black-clad gunman roaming the hallways, firing at anyone he sees, but those attacks are considerably less common than the ones aimed at specific victims.

Cheers, for example, shot the other teen after a feud that peaked, investigators said, in an off-campus confrontation days earlier. Although determining motive is not always possible, our report found that targeted shootings were about three times as common as those that appeared indiscriminate.

This underscores just how difficult it is for schools to stop most shooters, particularly in a country with more than 250 million guns. The majority intend to harm just one or two people, so the attacks typically end within seconds, leaving little or no time for staff to intervene.

Keeping weapons out of schools has proved just as difficult. At Mitchell High, students had passed through metal detectors one week earlier, but they weren’t being used the day Cheers brought his pistol into the building. Even schools that screen students every day sometimes fail to prevent gun violence from spilling onto their campuses.

In targeted shootings, gang members or estranged husbands attack students and educators on campuses simply as a matter of convenience – the perpetrators know where their intended victims will be and when.

A year ago, in San Bernardino, California, a man who had long harassed his estranged wife walked into her classroom and, without a word, fired 10 shots from his revolver, killing her and also fatally wounding an eight-year-old. He then took his own life.

In 2016, just as hundreds of students were let out for the day from Linden-McKinley STEM Academy in Columbus, Ohio, a 16-year-old in a passing car opened fire and wounded two students – one 12, the other 15 – on the front lawn.

Cases such as that one, which was gang-related and didn’t kill anybody, seldom prompt demands for reform. The same is true of accidental shootings that cause injuries (at least 16 since Columbine) and suicides committed in a public space or that included a threat to other students (at least four have occurred over the same period).

The emotional damage children suffer from these shootings, however, can be just as crippling as what others endure during highly publicised assaults. A study published in the journal Pediatrics in 2015 concluded that kids who witness an attack involving a gun or knife can be just as traumatised as children who have been shot or stabbed.

“In some ways, the distress caused, especially when the victim is a child or other close family member, might even be worse,” says Sherry Hamby, a clinical psychologist and co-author of the study. “We don’t do enough to acknowledge the collateral damage of gun violence. We are asking too many to carry this burden.”

More than 700 students attended Linden-McKinley two years ago, and scores of them saw the carnage that unfolded during that drive-by.

“All I heard is these gunshots go off,” Ya’mya Wilson, a junior, told a TV station at the time. “I literally started crying.”

‘Living in chronic war zones’

The news was both infuriating and encouraging for Duke Bradley, principal at Benjamin Banneker High, an almost all-black school south of downtown Atlanta. A girl had spotted a classmate with a gun and reported it to an administrator.

Weapons of any kind are banned at Banneker, where in 2014, before Bradley arrived, someone had opened fire in the parking lot, injuring no one but forcing classes into lockdown. Still, the fact that the girl had come forwards last year, the principal said, told him that she wanted to learn in a place free from the violence plaguing her community.

After the gun was confiscated, Bradley confronted the boy, who was about 15. He asked whether he’d brought the pistol to shoot someone there.

“Of course not,” the teen told him, offended that Bradley would think that.

The boy had brought it, he explained, because he needed protection on his way to and from campus.

“It was sobering,” Bradley said. “We, as adults – sometimes even the ones that work in these schools – are insulated from the world that our kids come from.”

In November, another teen brought a gun simply because he had found it on the way. He, too, said he had no intention to hurt anyone, but it went off in a classroom, injuring two of Bradley’s students – and making Banneker one of at least four schools that have experienced two shootings since Columbine.

Our analysis found that 62.6 per cent of the students exposed to gun violence at school since 1999 were children of colour, and almost all those shootings were targeted or accidental, rather than indiscriminate.

These incidents rarely make the news. In part, that’s because far fewer people are injured, but it’s also, experts say, because of the outside world’s perception of kids who grow up in high-crime neighbourhoods.

“Often, we have this notion that, ‘Oh, they’re used to it’ – and that’s BS,” says Steven Berkowitz, director of the Penn Centre for Youth and Family Trauma Response and Recovery. “They’re not used to it.”

Berkowitz has for two decades treated inner-city children who encounter gunfire in their neighbourhoods as well as in their schools. The threat of violence in parts of Philadelphia, where he works now, is so relentless that some students keep their backs to the walls at all times – and often can’t explain why.

Many of those children are in states of hyper-vigilance, he said, and tend to perceive danger even where there is none, much like combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

These students are saying: ‘No, no – these things are happening because you all can’t figure it out.’ They’re angry, and I think that anger is appropriate. And I hope they don’t let us get away with it

“I think these mass school shootings are absolutely horrific,” he says, but “it’s much more insidious and potentially really life-altering to have this ongoing danger… It’s not different than kids living in chronic war zones.”

Earlier this month, in Birmingham, Alabama, 150 miles west of Banneker High, another gun discharged at another school attended almost entirely by black children. Police, at least initially, suspected it was an accident.

It happened in a classroom, just as students were leaving for the day. The round pierced the heart of Courtlin Arrington, who died one month shy of her 18th birthday. She was a senior, headed for college. She wanted to become a nurse.

The same week, Javon Davies, a sixth-grader at a Birmingham middle school, came home and told his mom, Mariama, that he and his classmates had spent the day in lockdown.

“Somebody said they was going to shoot up the school,” she recalls him saying.

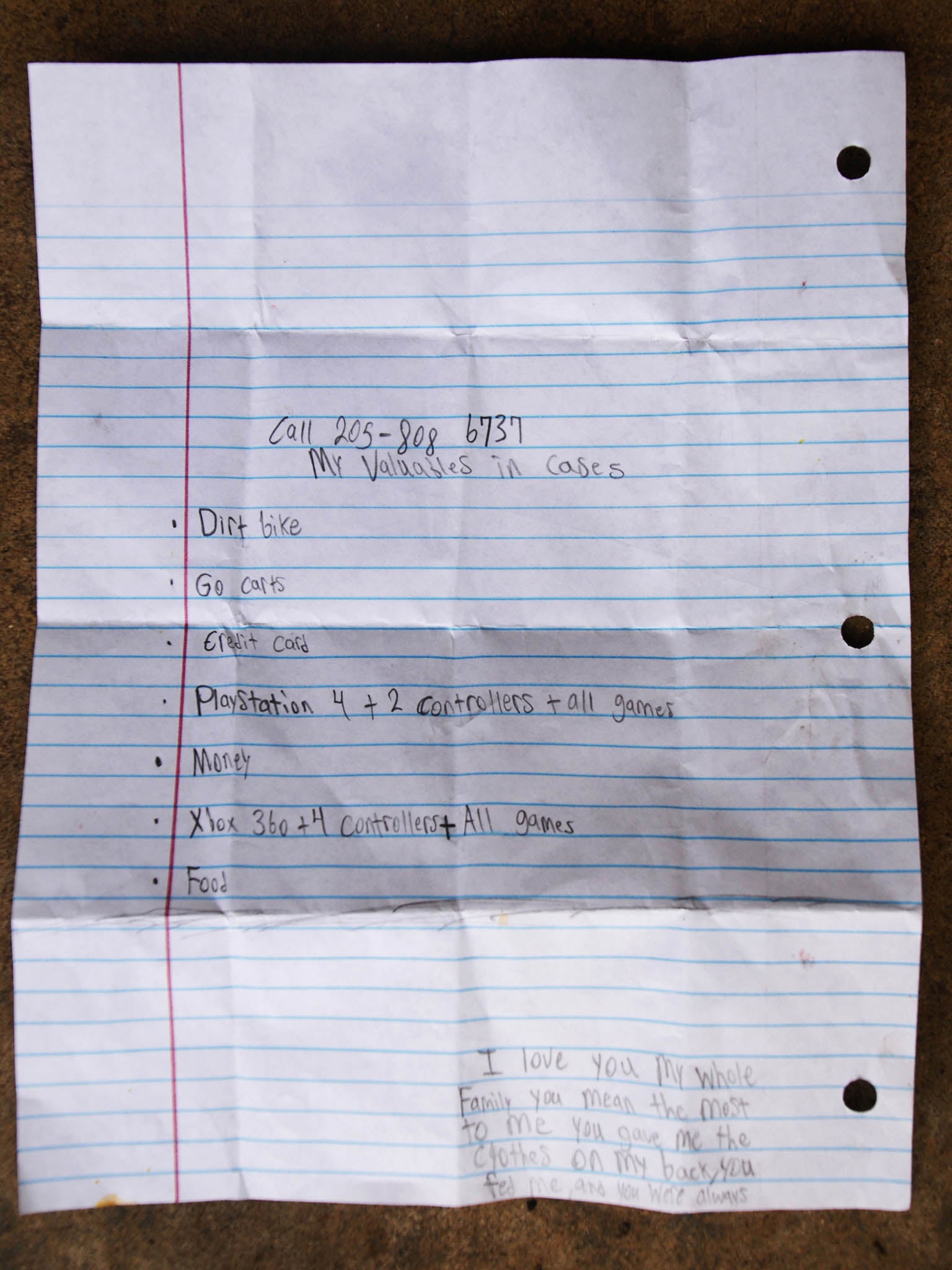

Javon, who is 12, had heard about Courtlin’s killing, just as he had heard about Parkland. He and a friend suspected that they, too, might die at their school, so each of the boys wrote a will.

“Mom,” the other sixth-grader wrote in print letters, “I want to give my friend Javon every thing that I own – that includes the Xbox and games and controllers and all that comes with it.”

In Javon’s instructions, he listed his PlayStation 4, his Xbox 360 and his dirt bike.

“I love you, my whole family, you mean the most to me,” he wrote. “You gave me the clothes on my back, you fed me and you were always by my side.”

‘It’s not like on TV’

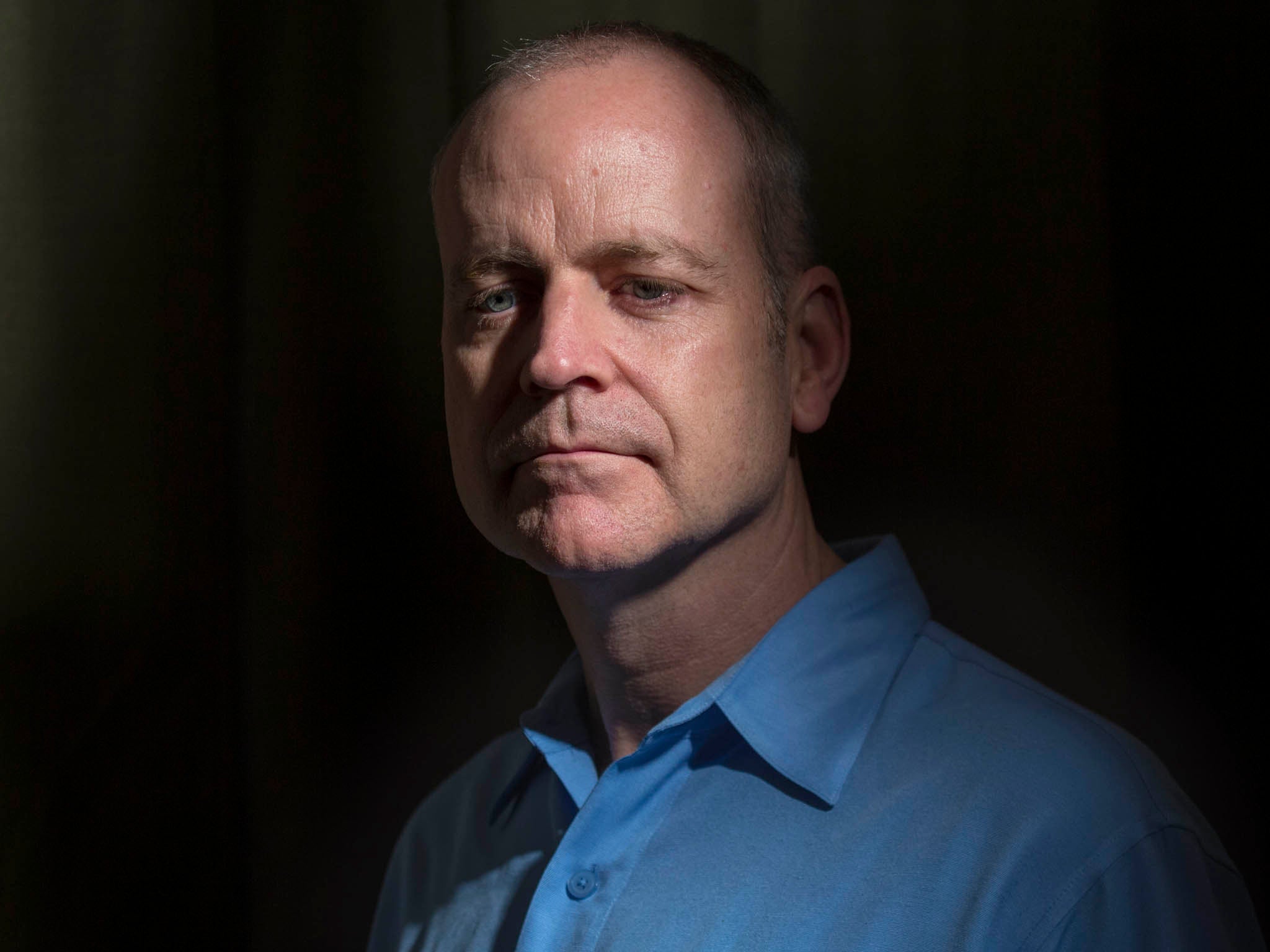

When Ed McClanahan first saw the teenager holding a .357 Magnum revolver in the middle of North Thurston High’s commons, the resource officer pointed his gun, but he couldn’t fire. All around the shooter, who had already sent a round into the floor and another into the ceiling, were other students, many running in terror, some frozen in confusion.

“It’s not like on TV,” McClanahan says. “You can’t just start blasting away with your gun. You could hit someone else, and that would be the worst thing in the world.”

He shifted his position, finding an angle that placed the gunman between him and a trophy case on that morning in 2015 in Washington state. McClanahan slid his finger on the trigger, and just as he began to apply pressure, a teacher tackled the 16-year-old.

In the nation’s capital, and in states across the country, lawmakers are debating how best to protect kids in schools, and much of the disagreement has centred on whether to hire more resource officers, arm teachers or do both. The answer to a key question – how effectively can someone with a gun protect a school from someone else with a gun? – is almost always missing from the discussion.

Our analysis found that gun violence has occurred in at least 68 schools that employed a police officer or security guard. In all but a few of those incidents, the shootings ended before law enforcement of any kind interceded – often because the gunfire lasted only a few seconds. Prolonged attacks, of course, can be even more fraught, as McClanahan’s experience illustrates.

Of the nearly 200 incidents of school gunfire we identified, only once before this week has a resource officer gunned down an active shooter. In 2001, an 18-year-old with a 12-gauge pump-action shotgun was firing at the outside of a California high school when the resource officer rounded a corner and shot him in the face.

Whether that happened again on Tuesday at Great Mills High in southern Maryland – where a 17-year-old gunman was fatally wounded after being confronted by a resource officer – remains unclear; investigators have not said whose bullet ended the teen’s life in an incident that also left two other students injured.

The NRA and other gun rights advocates have long argued that on-campus police deter school shooters. But do they?

Our analysis shows that resource officers or security guards were present during four of the five worst rampages: Columbine and Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Marshall County High in Kentucky earlier this year and Santana High in California in 2001.

At least once, however, the threat of encountering resistance influenced an alleged school shooter’s plan. In 2016, a 14-year-old in South Carolina attacked his elementary school rather than his middle school in large part because the latter, investigators said, had armed security.

And, in several instances, resource officers appear to have saved lives without ever pulling a trigger.

In 2010, after a man pointed his .380 semi-automatic pistol at a principal in a Tennessee high school, Carolyn Gudger, a resource officer, drew her own weapon and shielded the administrator. The standoff continued until other officers arrived and killed the intruder, who never fired but refused to drop his gun.

Introducing weapons into schools for any reason, however, comes with real risk.

In 2004, a security guard approached a 16-year-old student she suspected of smoking marijuana behind a high school in New Orleans. After the student pushed her, she later told investigators, he appeared to reach for something under his shirt, so she shot him in the foot. The teen, however, was carrying neither drugs nor a weapon.

There’s this mythical idea that you can teach kids to not want to handle a gun. Curiosity and impulsiveness are always going to trump your education of that kid

Two years ago, a resource officer in Michigan negligently fired his .380 Sig Sauer semi-automatic handgun, sending a round through a wall and ricocheting around a classroom – occupied by 30 students – until the bullet grazed a teacher’s neck, leaving a scratch. The officer, Adam J Brown, later tossed the bullet in the grass in an attempt to hide the evidence, and he was eventually sentenced to a month in jail.

Those opposed to arming teachers point to incidents like these as the reason. If law enforcement professionals with extensive training to handle firearms make mistakes with them, what might go wrong if educators with far less training carry the same lethal weapons?

Just last week, an armed teacher at Seaside High in California inadvertently fired his gun into the ceiling, leaving two students injured by falling debris and a third by a bullet fragment.

And more than once, suicidal teens have sought out confrontations with armed resource officers at their schools. In 2008, a 17-year-old in California attacked one with a baseball bat in what police said was an attempt to force the man to kill him, which he did. A year later, in South Carolina, a 16-year-old struggling with depression stabbed a resource officer seven times with a bayonet before being shot to death.

For McClanahan, who’s now retired, a resource officer’s most essential role is to intercede well before an act of gun violence occurs. He and senior administrators would regularly discuss potentially dangerous students, and at least 10 times during his decade working in schools, he dealt with kids who had made serious threats, either to classmates or online. In each case, McClanahan said, he and other officers visited the students’ homes and asked to search their bedrooms.

But the teen who fired the two rounds at North Thurston had just recently enrolled. He had a troubled history, McClanahan said, but he’d never made a threat or talked about bringing a weapon to school. Resource officers can only do so much, he said, stressing that, in America 2018, the responsibility to prevent school shootings falls just as much on other students, teachers, coaches, neighbours, friends and, perhaps most of all, parents.

The teenager McClanahan nearly shot, he said, had gotten the .357 Magnum from his father’s sock drawer.

Where do shooters get the weapons?

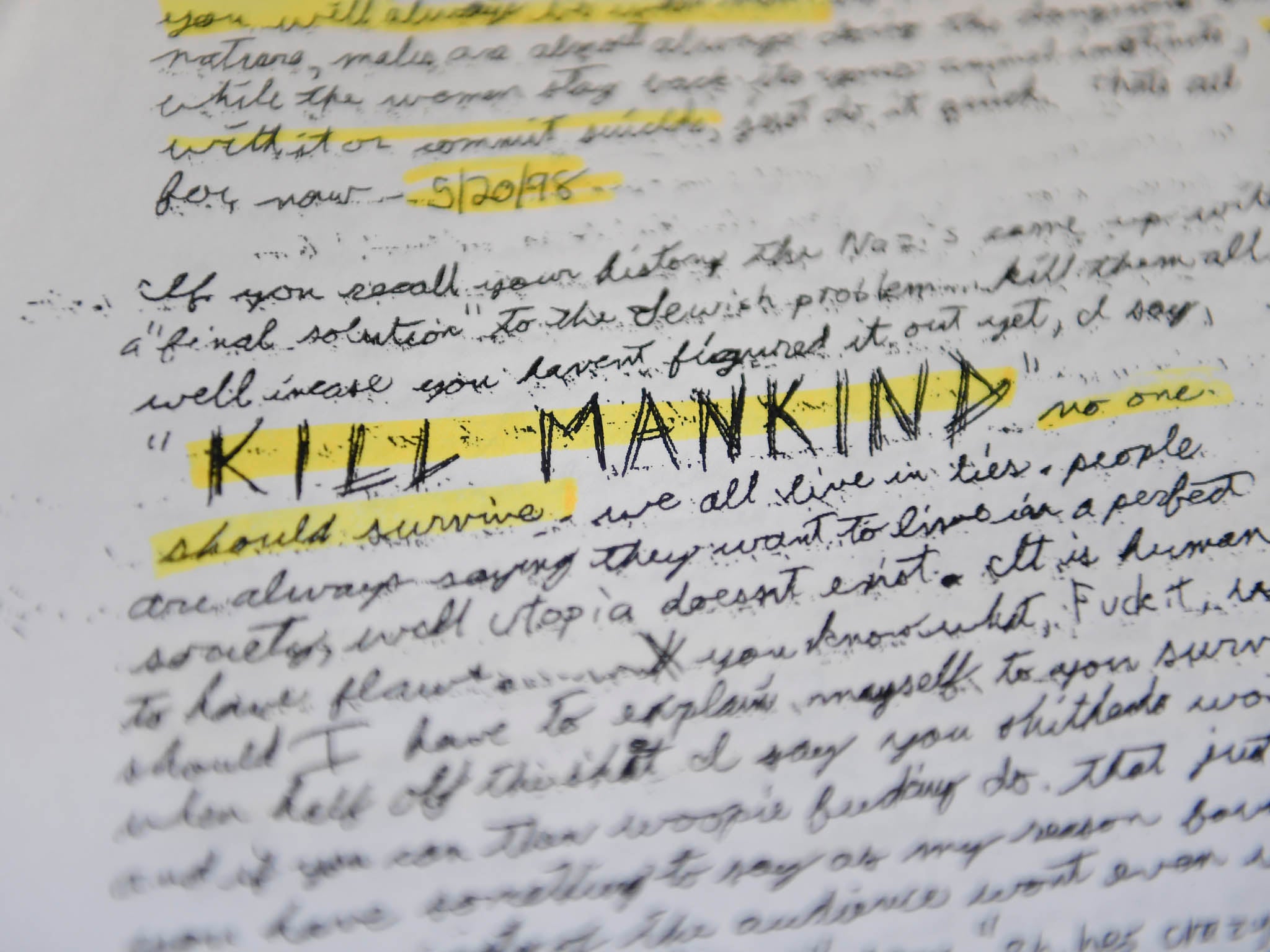

“We... have... GUNS!” Eric Harris exulted in a journal after listing each one he and Dylan Klebold had obtained, none more important to their plan than the Hi-Point 9mm Carbine rifle, with its 250 rounds of ammunition. It was November 1998, five months before the massacre at Columbine.

“I’m still waiting for a mass shooter who eschews 9mm pistols and instead buys an AK-47...” Adam Lanza declared on an online message board, describing a gun much like the Bushmaster XM15-E2S rifle in his home. It was January 2011, 23 months before the massacre at Sandy Hook.

“Arsenal,” Nikolas Cruz announced on Instagram along with an image of a bed strewn with firearms around his AR-15 rifle. It was July 2017, seven months before the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

A generation of school shooters aspire to kill just as many people as Harris, Klebold, Lanza and Cruz, but what sets them apart – and made them famous – are the extraordinarily deadly weapons they used. Our report found that the number of people who died in those three attacks accounted for 43 per cent of the total death toll in school shootings over the past 19 years.

Handguns, though less lethal, are far more common. More than 106,000 students have been exposed to gunfire during at least 113 incidents that involved only a pistol.

It’s no longer the default that going to school is going to make you feel safe. Even kids who come from middle-class and upper-middle-class communities literally don’t feel safe in schools

And where do most shooters get their weapons?

In cases where the source of the gun could be determined, more than 85 per cent, according to our analysis, brought them from their own homes or obtained them from friends or relatives. Although seven in 10 of the shooters were under 18, adults in only 14 states and DC can be held criminally liable for negligently storing firearms where minors can reach them, according to the Giffords Law Centre to Prevent Gun Violence. Even the laws in those states, researchers say, are often not enforced.

Denise Dowd, an emergency room doctor at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Missouri, has argued for years that no youth should have unsupervised access to a gun. Dowd has researched the consequences for the American Academy of Pediatrics and seen them first-hand during a four-decade medical career in which she’s treated at least 500 juvenile gunshot victims.

“You have to separate the guns from the kids – the thing that does harm from the thing that’s harmed. That’s a tenet of injury prevention,” Dowd says. “There’s this mythical idea that you can teach kids to not want to handle a gun. Curiosity and impulsiveness are always going to trump your education of that kid.”

On the morning of 15 May 2017, Gage Meche, then seven, walked into his first-grade class and hung up his blue Nike backpack, then turned around. On the floor in front of him was a gun. It had just fallen out of another boy’s bag, and when a girl Gage had known since they were toddlers picked it up, the pistol fired, discharging a .380 round that blew through his stomach, tearing into his intestines and nicking a vena cava vein, which carries blood to the heart.

The boy who’d brought the gun had found it at home, investigators say. His father, Michael Dugas, had given the weapon to his older son, who was 17. The teenager kept it in his room, loaded, unlocked and inside a bag that hung on the wall.

Soon after the shooting, Dugas was charged with two misdemeanours, eventually receiving six months in prison for his negligence.

Gage, meanwhile, endured four surgeries, then had to learn to walk and eat again. Now eight, his 40-pound body hurts almost all the time, says his mother, Krista LeBleu.

The girl who accidentally shot him still struggles with guilt and post-traumatic stress. At a church camp last summer, a water pistol fight broke out, and when she saw the plastic guns, the girl began to weep.

Gage has changed, too, his mother says. He had been so excited to flip the coin before a local football game a few months ago, but when the team rushed onto the field, someone fired a cannon. The boy’s knees buckled, and he collapsed to the grass, trembling as he curled into a ball. He still has nightmares, but he tells his parents they’re too scary to talk about. Gage is also more aggressive than before, sometimes erupting for no reason. Afterwards, he can’t explain what happened.

“I don’t know why I’m so bad,” he says.

What we know about school shooters

Twenty-seven days after Adam Lanza walked into a Connecticut elementary school holding a semi-automatic rifle, a pale, red-headed teenager walked into a science class nearly 3,000 miles away holding a shotgun.

Bryan Oliver, a junior, aimed the barrel at a schoolmate who he claimed had bullied him at Taft Union High in California, then pulled the trigger, blasting a hole in the boy’s chest.

He had intended to shoot at least one other young man, investigators say, but his second shot missed. Their teacher, whose head was grazed, calmed the teen, eventually persuading him to surrender his weapon.

There is no archetypal American school shooter. Their ranks include a six-year-old boy who killed a classmate because he didn’t like her and a 15-year-old girl who did the same to a friend for rejecting her romantic overtures. They also come from backgrounds of all kinds. In some school shootings, the race of the assailant isn’t reported, but in those that are, our report found, the shooter’s race almost always reflects the campus’s population, with white shooters attacking predominantly white schools and black shooters firing in predominantly African-American schools.

Our analysis also shows that dozens of gunmen shared certain characteristics, and few of them exhibited as many of the most common traits as Oliver did. At the time of the attack, he was 16 – the median age of school shooters. He is male, part of a group that outnumbers female shooters 17 to one. Like most, he had intended to kill specific people. Also like most, he showed no signs of debilitating mental illness, such as psychosis or schizophrenia.

That last finding undermines what gun rights advocates and President Donald Trump have focused on in Parkland’s aftermath. At a convention for political conservatives last month, Wayne LaPierre, head of the National Rifle Association, blamed gun violence in school on, among other things, a “failure of America’s mental health system”.

We don’t do enough to acknowledge the collateral damage of gun violence. We are asking too many to carry this burden

Although Nikolas Cruz showed signs of psychological problems before he allegedly killed 17 people, researchers have consistently concluded that they seldom play a role in shootings or violence of any kind.

“Framing the conversation about gun violence in the context of mental illness does a disservice to the victims of violence and unfairly stigmatises the many others with mental illness,” Jessica Henderson Daniel, president of the American Psychological Association, said in a statement. “More important, it does not direct us to appropriate solutions to this public health crisis.”

Identifying real solutions has proved exceedingly difficult, in part because the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention stopped studying gun violence 22 years ago. At the time, the Republican-led Congress mandated that no CDC funds “may be used to advocate or promote gun control”, language that, though vague, halted almost all study of gun violence – now, according to a recent review, the third leading cause of children’s deaths.

The dearth of government-produced data is particularly frustrating for Peter Langman, a psychologist who analyses school shooters.

“To me,” he says, “it doesn’t make any sense that whole realms of research are not possible.”

At trial in 2014, Oliver testified that he had been bullied, but he also acknowledged that the teen he shot – who needed more than 20 surgeries – had only annoyed him. Oliver insisted that he had blacked out that day and remembered nothing about what had happened until he fired the first round.

Prosecutors, however, note that Oliver, later sentenced to 27 years in prison, had loaded a shotgun, walked to school and, according to surveillance video, repeatedly looked around to see whether anyone was watching him.

Grief, guilt, fear

One day in 2008, Samantha Haviland sat on the floor of a school library’s back room, the lights off, the door locked. Crouched all around her were teenagers, pretending that someone with a gun was trying to murder them.

No one there knew that Haviland, then a counsellor in her mid-twenties, had been at Columbine nine years earlier. On that day, 20 April 1999, she had been in the cafeteria, selling chips and soda from a food cart to raise money for the golf team. Haviland, always an overachiever, had taken second place at a tournament the day before and felt so good about it that she’d worn a blue dress and high-heeled clogs to school. As hundreds of kids ate their lunches, she and three friends talked about prom, which they’d attended the previous weekend.

Then two girls burst into the room. Someone had been shot, they screamed. Someone had a gun.

Haviland froze, but her friends grabbed her, and they fled into the back of an auditorium. Moments later, she heard four or five shots and an explosion. Everyone sprinted out as Haviland briefly paused to take off her shoes. Barefoot, she ran after them and into the hallway, and just as she reached one door, it closed in front of her. A teacher in another part of the building had pulled the fire alarm and, as she would later learn, it saved her life, because down that corridor, Harris and Klebold were slaughtering anyone they could find.

Afterwards, as the shock and grief solidified her plan to become a counsellor, Haviland didn’t get counselling herself. She didn’t deserve it, she thought, not when classmates had died or been maimed. Many others had suffered far more, Haviland decided. She would be OK.

But now there she was, a decade later, sitting in the darkness, practising once again to escape what so many of her friends did not. Then she heard footsteps. Then, beneath the door, she saw the shadow of an administrator who was checking the locks. Then her chest began to throb, and her body began to quake and, suddenly, Haviland knew she wouldn’t be OK.

Researchers who study trauma still aren’t certain why people who experience it as children react in such different ways. For some, it doesn’t surface for years, making the effects harder to trace back to their origin. For others, the torment overwhelms them from the start and, in many cases, never lets go.

Karson Robinson was six when a teenager opened fire on the playground of his elementary school in Townville, South Carolina, on 28 September 2016. Three days later, on his seventh birthday, he learned that his beloved friend, Jacob Hall, hadn’t survived the bullet that hit him. That’s when the guilt took hold. Karson had vaulted a fence and run at the first sound of the gunfire.

Maybe, Karson thought, he could have saved Jacob, the smallest child in their class, if he hadn’t fled. At home, Karson began to explode in anger, breaking anything he could reach. Other times, he insisted that everyone hated him.

It’s much more insidious and potentially really life-altering to have this ongoing danger… It’s not different than kids living in chronic war zones.

In October, before a doctor finally diagnosed the boy with PTSD, he had a party for his eighth birthday, and at the end, they released balloons into the sky for Jacob. Afterward, he walked off by himself. His mother followed, asking what was wrong.

“I should have waited for Jacob,” he told her.

Haviland thinks a lot about the thousands of children like Karson who, she contends, America has done so little to protect since Columbine. Many of Haviland’s former classmates have found success and happiness, but others have tried to ease their pain with drugs and alcohol. Some have considered killing themselves.

One high school friend sent Haviland a message online a few weeks ago, saying that, since the Las Vegas slaughter this past October, she’d been so stricken with anxiety she could barely leave her house.

A decade ago, after Haviland’s panic attack in the library, she finally got therapy and has come a long way since. She goes to movies and malls and political rallies. She has so often told her story – of hearing the shots, taking off her shoes, sprinting barefoot through the hallways – that telling it again doesn’t wreck her anymore.

She knows, though, that the trauma remains.

Three years ago, someone accidentally pressed a panic button in the school where she was working, signalling to police that a shooter was in the building. Haviland wasn’t there at the time, but she pulled up in her car just as the officers did. Then, in front of her, she saw students streaming outside, their hands in the air.

She began to sob.

The Washington Post’s Allyson Chiu, Alex Horton and Jennifer Jenkins contributed to this report

Methodology

The Washington Post spent a year determining how many children have been affected by school shootings, beyond just those killed or injured. To do that, reporters attempted to identify every act of gunfire at a primary or secondary school during school hours since the Columbine High massacre on 20 April 1999. Using Nexis, news articles, open-source databases, law enforcement reports, information from school websites, and calls to schools and police departments, The Post reviewed more than 1,000 alleged incidents but counted only those that happened on campuses immediately before, during or just after classes.

Shootings at after-hours events, accidental discharges that caused no injuries, and suicides that occurred privately or posed no threat to other children were excluded. Gunfire at colleges and universities, which affects young adults rather than kids, also was not counted.

After finding 197 incidents of gun violence that met the criteria, reporters organised them in a database for analysis. Four schools experienced two episodes of gunfire over the past 19 years, which is why the final school total was 193. Because the federal government does not track school shootings, it’s possible that the analysis did not find every incident that would qualify.

To calculate how many children were exposed to gunfire in each school shooting, The Post relied on enrolment figures and demographic information from the US Education Department, including the Common Core of Data and the Private School Universe Survey. The analysis used attendance figures from the year of the shooting for the vast majority of the schools. Then The Post deducted 7 per cent from the enrolment total because that is, on average, how many students miss school each day, according to the National Centre for Education Statistics. Reporters subtracted 50 per cent from a school’s enrolment if the act of gun violence occurred just before or after the school day.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks