Schizophrenia part three: How reflecting on past mental health through art is more than just therapy

The third and final instalment from Patrick and Henry discusses life after being institutionalised and how turning the latter’s demons into a success – as a novel and paintings – worked as a morale booster and began to outweigh the calamities of the past

When Henry was sunk deep in psychosis, he would draw what he called “a rune” – a sort of ideogram – again and again on a piece of paper. When he was slightly better, this would change to his tag or graffiti name again drawn time after time on different sheets of paper. The next step in his return to rationality was the gradual appearances of people, houses, streets, cities, trees and birds in his pictures. One showed a lonely barefoot figure – probably himself – drawn in black and white, sitting smoking a cigarette and turned away from the coloured scene behind him – a graffiti-covered train going into a tunnel.

People sometimes have an over-simple view of art as an effective therapy for mental illness, as if the act of putting one’s troubles on paper automatically mitigates them and brings them under control. There is something in this, but it was rather the slow acquisition of a real skill that seemed to do Henry most good over the years. This is not to say that occupational therapists did not do Henry a lot of good, in fact he thinks they were key to his survival, because the therapists gave him something to do and were neutral figures he could talk to, unlike doctors and nurses whom he saw as figures of authority who were denying him freedom.

Once out of hospital, Henry and other long-term patients suffered from the effects of “institutionalisation”, something impossible to avoid because for years they had needed the safety of an institution to survive. Means of coping with life after years in hospital are difficult to reacquire – and lack of such skills may have been a cause of the original breakdown – after years of illness inside or outside hospital, former patients face loneliness, joblessness and general unhappiness, which is why so many relapse, take refuge in drugs and alcohol or commit suicide.

As Henry began to recover in the Cygnet hospital in Beckton, east London, in 2008, I would take him out and we would often sit in a student café off Brick Lane. “Do you think I am a failure, Dad?” he would say to me sadly. By then he was 26 and was very conscious that his school friends in Canterbury had got jobs or might be married and have children while he had done nothing.

I began to think if there was any way I could bring success into Henry’s life. It occurred to me that his grim experiences might be used to his advantage. He knew all too much about what it was like to have a severe psychosis and what it was like to live in a mental hospital. He was ideally placed to write from the inside what these were like. I would write a narrative, what it was from the outside to experience the same things. Henry wrote his chapters and I wrote mine and, in the event, the book included a long excerpt from Jan’s diary about when Henry had been found in the snow. I thought we could serve a useful public purpose by telling people what mental illness was really like.

The book, Henry’s Demons: Living with Schizophrenia, a Father and Son’s Story was published in 2011, was well reviewed and became an instant best seller. I had wondered if Henry would find being interviewed about the book too stressful or painful, but, after initial nervousness, he enjoyed it and was good at it. I had told him truthfully by way of encouragement that he was always going to know far more about the topic of the book than anybody who was asking him questions. He found this to be true and he responded much more readily to questions from a BBC interviewer and from audiences than he had ever done to hospital psychiatrists, whom he distrusted as being responsible for his incarceration.

The success of the book did Henry good. Soon after it was published we were walking up Gray’s Inn Road for an interview when Henry ran into an old school friend and asked him what he was doing. He said he was working for NBC, the American television network and asked Henry what he was doing. “I’ve just written a book,” he replied and later added to me, when the friend had moved on: “I enjoyed saying that.”

The book was a morale booster. People would say to me that they supposed that the very act of putting what happened to him on paper was therapeutic for Henry. I could see what they meant, but I thought that the beneficial effects of the book would dissipate over time and it would be as a painter that he would rebuild his life. Above all he needed productive work.

Soon after Henry had left the halfway house for former mental patients in Lewisham where he was living, he went to see a psychotherapist. After talking to Henry for an hour, he said: “What you need most in your life is not therapy but structure,” by which he meant a settled pattern of activities around which Henry’s life would revolve. Henry himself decided that it would be best if he went back to art college, this time the University of Creative Arts at Canterbury, where he had lessons, work to produce, skills to learn and teachers and students with whom he had to interact every day. It was important also that his pictures and essays were judged just like those of other students without him being given special consideration as a former mental patient. The routines of work and study visibly did Henry good at many levels, including the simplest one of giving him a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

Henry was by now living largely independently in his flat in a house in Herne Bay where there was a nursing staff available during the day in case of need. He often felt lonely and bored, so he started to learn the guitar and joined a chess club and a boxing club, though he found the punishing physical exercise in the latter difficult to sustain. More successfully, he was part of a drama group made up of people whom he liked and all of whom had suffered mental health problems in the recent past. Like everybody else his degree of happiness stems from a succession of small successes and I believe that these are beginning to outweigh the calamities of the past.

Surviving mental illness – by Henry Cockburn

I absconded from hospital about 30 times. I suppose it was my way of dealing with things, I got such a rush jumping over the fence – instant liberty. I would never last long, my record of being on the run was about nine days. The nurses had to watch me like a hawk, I would sit by the double doors waiting for someone to accidentally leave the key in the lock, or leave the doors open. I believed at the time that I would make it on the run, that I would stay on the outside for years, I thought that I would get a job and find a house. But for me living on the run for more than a week was not possible, I always ended back right where I started – on the ward. Besides, being on the run is not quite what it’s cracked up to be; you are always looking over your shoulder, or wondering where the next meal is coming from. The picture shows two detached looking patients playing pool whose game is interrupted as they look through a window at me about to escape over a fence pursued by a nurse.

This leads me to the next painting “Institutionalised”, this shows me zombified watching telly, while in the background the other patients are in a queue waiting for their medication at a hatch. There is no natural light in this painting, there aren’t even any windows – just the light from the television and the electric light overhead. This painting is very much based on reality, it is the room drawn from my memory. It tries to capture the oppressive atmosphere of being in an institution. This is how it is, day in and day out. I suppose, in hindsight, at least back then we were allowed to smoke; nowadays that liberty has been taken away, and if you want to smoke, you have to smoke off the hospital grounds. The thing that strikes me about being institutionalised is that you don’t know that you’ve been institutionalised, because you take it for granted. It doesn’t strike you as odd that you are not cooking your own food, or earning your own money, paying your own bills. Recovery takes a long time, a lot of support, and a lot of initiative on the part of the patient. To anyone who says that rehabilitation is a waste of public money, I would say that if you want patients to recover, it is the only way to get them back on their feet. During the years I was incarcerated, the main thing that kept me alive was the occupational therapists, doing activities like yoga, weightlifting, art therapy, music therapy, cooking. Without something to do, to occupy your mind, desperation can set in, and when one is desperate one can take desperate measures. I contemplated suicide twice while I was in hospital, fortunately I didn’t go through with it.

One of the things that really helped me with dealing with this, was finding faith. This is the inspiration for my next painting “Hope”. It shows me in an empty church praying. The church interior in the painting is based on two churches that I have attended, the one Baptist church that I currently go to now in Canterbury, and the church I went to when I was briefly at the Maudsley Hospital in Beckenham. Having faith, faith that we were created and that we have a purpose in living this life, has given me strength. When times get dark, and I despair, belief that I am not alone and that there is a God looking down on me whom I can pray to and who does not judge me takes a burden off of my shoulders. Since the beginnings of my psychosis, I have tended toward something spiritual and spirits guide us and that the birds and the trees hold something more than what we take for granted, day to day. Believing in something else helped me get out of the hole that I had dug for myself, and at the end of it all become a better person.

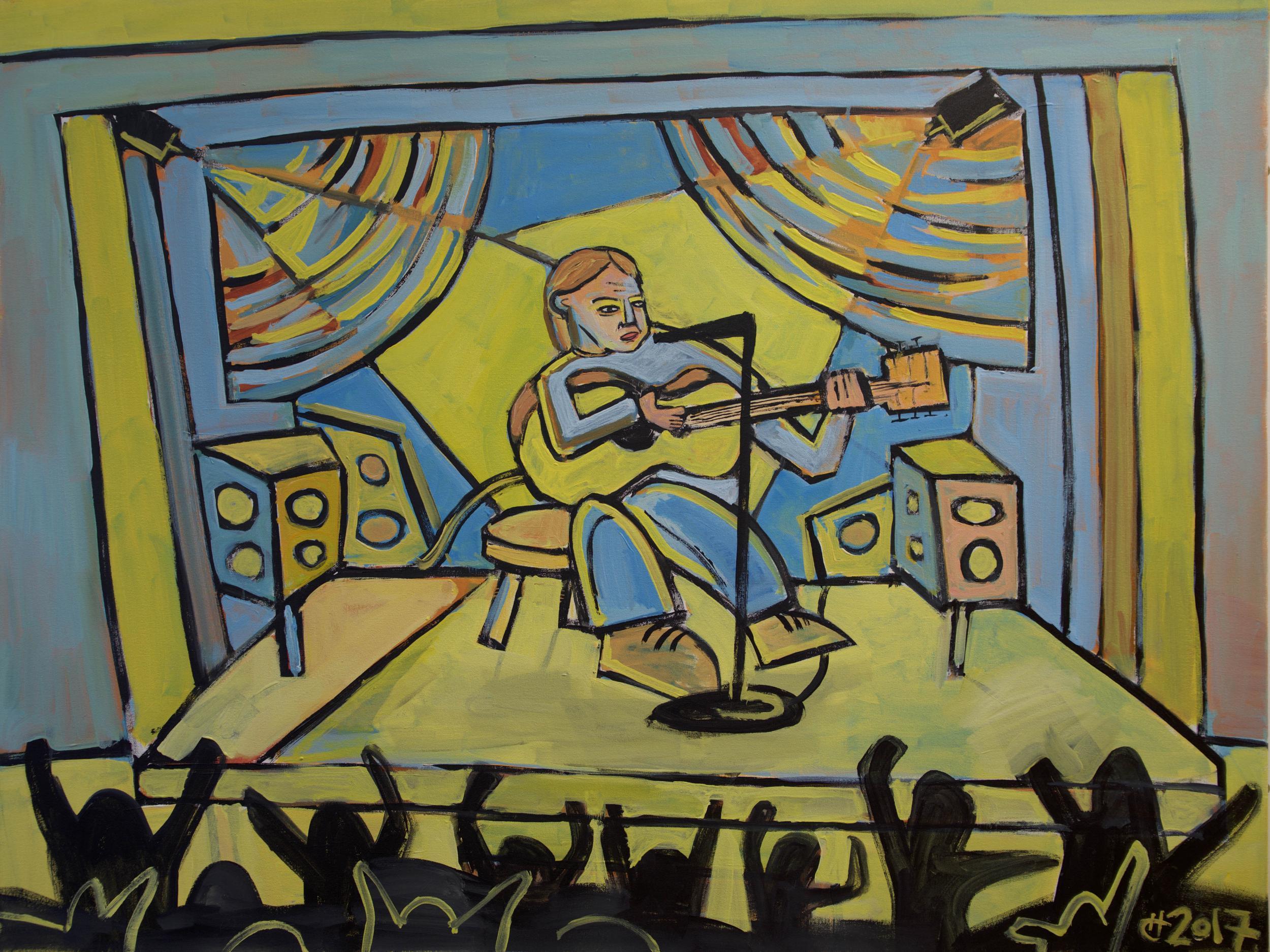

The series of paintings that I have done has turned something that was primarily a negative experience into something positive. Although the content is dark, I have used a vibrant palette within the paintings. The sequence of paintings ends with me playing guitar on stage in front of a big audience. Since my first spiritual experience talking to a tree that told me I could rap, I have pursued an interest in music – not just rapping but also playing guitar. I have done a few gigs and open mic nights and it is my dream to record an album. The painting of me playing in front of a large crowd is partly prophetic, it is one of my dreams that hasn’t come to fruition yet.

But I’m sure that it will, I never dreamt that I would get out of hospital, let alone do a series of paintings about it. This series was not easy to make and at points I got stuck, not knowing how to convey my story and make it have an impact. Most of the people I talked to about the paintings said that a friend or a relative had had a mental illness, or had spent time in a mental institution. This series is not just about me telling my story or even solely about mental illness. Looking back, I think it is like any other struggle in life, though worse than most, but I have survived and come out stronger the other side. I would like to believe that others can do so too.

Henry Cockburn’s series on surviving mental illness will be exhibited 18-27 September as part of the Folkestone Triennial art festival at the Lilford Gallery, 8 Old High Street, Folkestone, Kent CT20 1RL

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks