Rebecca Miller on the mother of all subjects: her father

Her new documentary for HBO confronts the complicated legacy of Arthur Miller, who wrote ‘Death of a Salesman’ and married Marilyn Monroe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Arthur Gelb, the human pinball machine who served for decades as The New York Times culture czar, had many fantastic stories. But my favourite was his attempt to assign our music critic a feature on Wanda Horowitz.

Arthur had met her at a dinner party one night and was intrigued by what life must be like when you are sandwiched between two artistic geniuses. Wanda was the daughter of Arturo Toscanini and the wife of Vladimir Horowitz.

The critic, Harold Schonberg, invited her to lunch, where she promptly had a fit. “Why am I talking to you about the miserable life I’ve been through with these two men!” she shrieked. “They ruined my life and they should roast in hell!” Interview over.

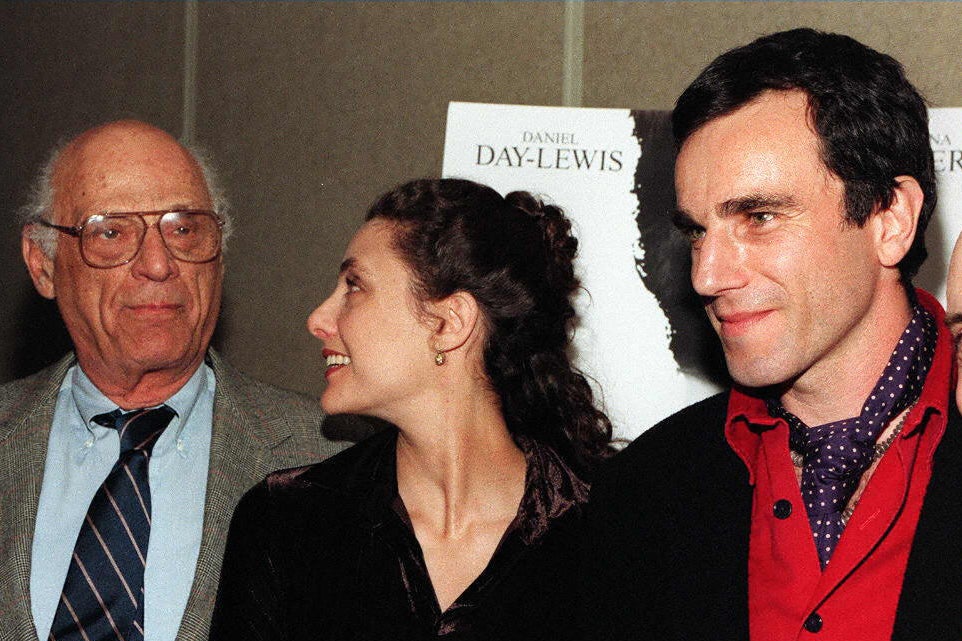

So when I find myself having lunch at Morandi in the West Village with Rebecca Miller, the daughter of Arthur Miller and the wife of Daniel Day-Lewis, I can’t resist asking her: what is it like to be sandwiched between two artistic geniuses, catering to both?

Rebecca Miller, being as airy as Horowitz was acerbic, simply laughs.

“I knew them,” she says of the Horowitzes. “They’d come over to our house and he’d bring his own food because he was worried he was going to get poisoned. She seemed like a fairly dark character and he was very sensitive. He would play on our ridiculous piano. I could see where Horowitz wasn’t a barrel of laughs to be married to.”

As the beloved daughter of one of America’s most famous playwrights, Miller met everyone who was anyone, all from a worm’s eye vantage point in their home in Roxbury, Connecticut.

“For reasons I still haven’t figured out, nobody would put me to bed when they had dinner parties, so I was expected to just go under the table,” she says of her father and her mother, the esteemed Austrian photographer, Inge Morath. “And there was a big trestle in the middle and I would lie on this five-inch trestle because I was very narrow and just listen and be in my own imagination. Our very greedy dachshund was down there, too, making laps, looking for scraps.

“It’s a life that’s gone now, a life of artists who believed that if a coffee pot was broken, you welded it back together. It wasn’t a fancy life and it was very much about work and about decency in a certain way. I remember the McGovern fundraiser in the barn that my father had when I was a kid. I wore purple hot pants thinking I was just so cool. And the Styrons and the Calders and all the people who lived in those hills in those days were there. They were bohemians in a way, but they were also very straight people. It wasn’t a bohemia or even Bloomsbury. They weren’t sleeping around. They were just hardworking people who drank a lot of wine at night.”

Miller, 55, has sky-blue eyes and long, dark wavy hair and is wearing a delicate cream blouse with origami sleeves, high-waisted black trousers, and on her fingers jewellery given to her by her husband: an oval aquamarine ring and a French Claddagh ring – a heart with a fleur-de-lis. I ask if she was ever intimidated by her lineage as she made her own name, first as a fiction writer and then as a screenwriter and director.

“I definitely went through periods of wishing I had been a child of unknown people,” she says. “Because I felt like I could’ve made my mark alone, and it pissed me off. I would have liked the chance to say things like the Monty Python guys did when they said something like, ‘When I was a child, we used to have to scrape the muck from the bottom of a pond.’

“But I think my parents, especially my mother, gave me a lot of confidence. My mother was told by the poet Anna Akhmatova that because I was female, she should spoil me so that I would not be anyone’s slave. I don’t think my mother spoiled me in a material way. I was raised to be kind to people. But I was really raised to be an artist, sort of the way some kids are raised to be tennis players. And I kind of stuck with the programme.”

Sheila Nevins, who shepherded Miller’s documentary about her dad, which made its premiere on HBO on 19 March, marvels at her friend. “Sweet Rebecca,” she says. “She should be crazy, going to psychiatrists every five minutes. And instead she came out like a buttercup, so lovely, so guileless, so unspoiled, so nice to waiters. You expect a star and you get your college roommate.”

In one of her short stories, Miller writes about her protagonist, a young woman named Greta: “At first her parents and their friends thought that she was ‘not gifted or tough enough to survive so close to the light of their parents’ world’.” The character’s father, a famous lawyer, notes: “Everyone has their own personal velocity.”

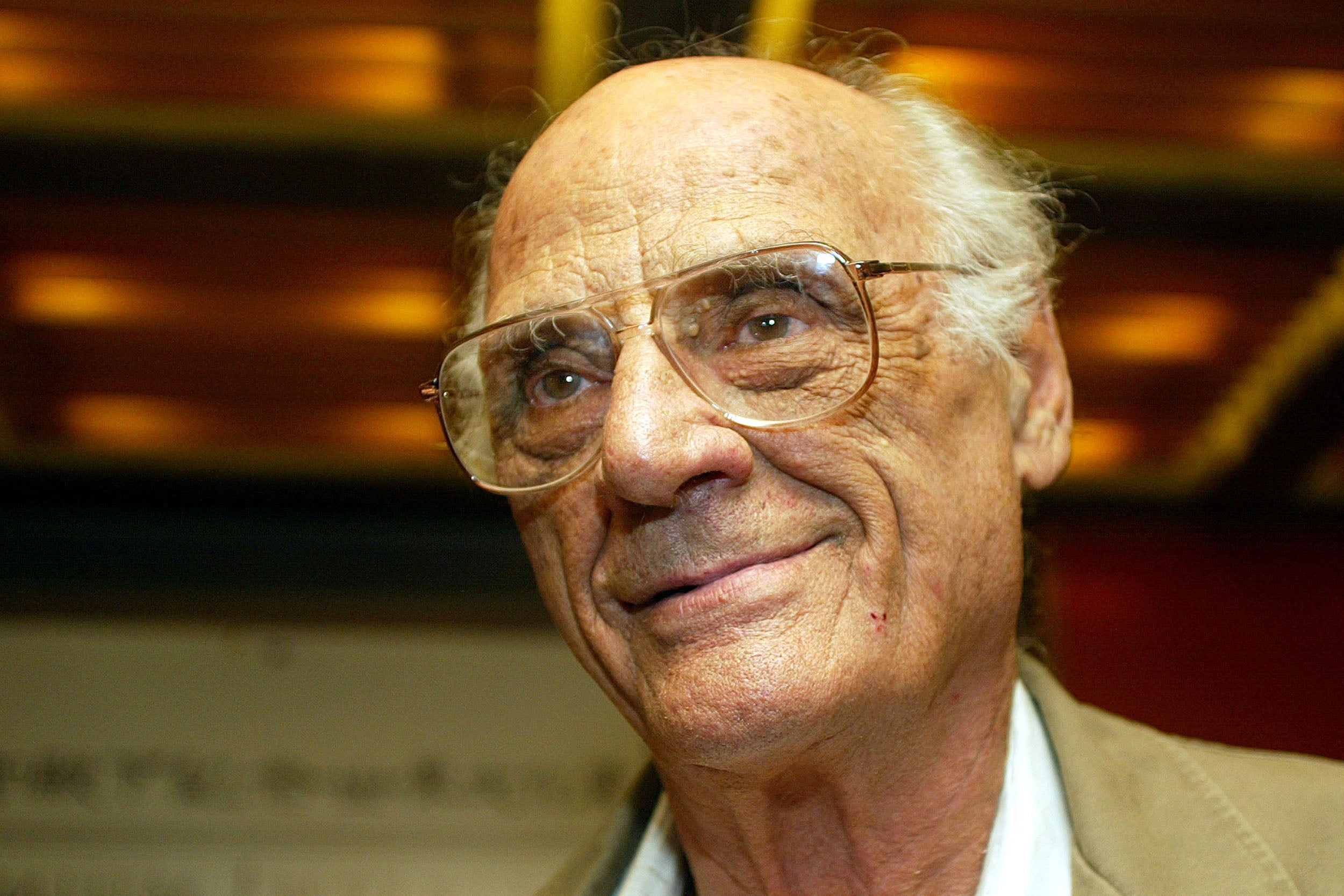

Arthur Miller got famous writing about fathers and sons. As he said in one interview: “The parent is always a mythological figure. It’s the basis of all mythology, after all. What’s Zeus? He’s the father. He’s the guy that throws thunderbolts – kills you. Or raises you up into glory.”

His daughter says: “I definitely feel like I lucked out being female with him. Because he was not the sort of person who wouldn’t have minded being metaphorically murdered by their sons, subsumed, overtaken or whatever. I got under the radar because I was female. But had I been male, I have a feeling we would have had a much different, more difficult relationship.”

I tell Miller that I was so strongly affected by Death of a Salesman when I read it in high school that I started crying when my brother told me he had gotten a job as a salesman. In her film, Miller interviews Mike Nichols, who directed a revival of Death of a Salesman on Broadway in 2012, and Nichols wonders if Arthur Miller “burned something out” when he wrote that play because “he came so close to the target”.

“I think there was almost a mystical property to the creation of that play,” Rebecca Miller agrees. “That remained a mystery to him for the rest of his life. How do you write that first act in one night? It’s almost a visitation. It was a raging fire that went through him.

“It’s an interesting story because, of course, part of the play is talking about the wrong dreams and how our society has built people up to want things that maybe they can never have, so they feel like failures when really all the things that they need are right around them. But, early on, he said he was standing in the back of the theatre once and he saw many people crying, and he was like, ‘Oh my God, did I make this too sad?’ That the pathos of Willy was so enormous that maybe no one was going to remember any of the social criticism.”

His daughter, growing up in a time when his reputation had fallen off, felt compelled to offer a vision of her father as she saw him. She began shooting VHS tapes of him when she was 21. “I realise, you know, that this is my sixth film but it’s also my first film,” she says. “I spent 18 months cutting it. It was quite an emotional process for me.”

She felt there was “a huge gap” between the cosy storyteller she saw at home, who enjoyed woodworking, and the cool intellectual she saw in interviews.

“He had a remoteness in interviews, because he was a shy person and he was very protective of himself, understandably at that point,” Miller says. “It was a feeling like, his warmth and his humour would never really come through.”

It was strange, she admits, to work on the sections about his first two wives, Mary Slattery and Marilyn Monroe. “How do you express his vulnerability with these women?” she says. “Which was a surprise to me. Because he had been lovely and jokey and cuddly with me, but he was hardly a romantic figure to me. That’s not how I saw him.”

She uses his journal entries and love letters to unfurl the relationships.

“One of my biggest surprises was how tender he was with Mary,” Miller says of her father’s first wife, who had been his college sweetheart and with whom he had a son and daughter. “I had never had a taste of that, so it was interesting to read those letters and say, ‘No, that really was a beautiful romance.’ Her character was very reserved. But it was important because she talked to him about the plays, he asked her about them. She was a little tough on him. He needed that. He did need a woman to adore him, though, that is for sure.”

Arthur Miller concedes in the movie: “I enjoyed being a father. I also enjoyed escaping being a father. I was always in and out of my skin because I just couldn’t be a father 24 hours a day and still do what I was thinking I had to do.” He said he worried that he would forget to pick up his son from school. About his first wife, he writes in his journal: “In all the feeling for Mary, I rarely see her face, rarely sense her. At this moment I fear to go home.”

After Miller gets besotted with Monroe, his first marriage quickly dissolves.

Rebecca Miller found that portraying her father’s passionate romance with Monroe was “very tricky.”

“I felt sometimes almost that I shouldn’t be in the room, I shouldn’t know all this stuff,” she says. “There was this one moment that we created a scene with still pictures where he seems to be looking at her and she’s standing there and he says, ‘You’re the saddest girl I’ve ever met.’ It was weird, but that was also the moment where I sort of transformed from a daughter into a filmmaker. And I also ended up sort of seeing how she was just a person, you know? Because there’s so much smoke around her. She would even tend to take up huge amounts of space in the film. I was constantly trying to cut it down again, because she has so much light coming out of her. So much charisma. I just said, ‘OK, how can we penetrate the mystery a little bit of this woman and this man and in the end find some clarity?’”

She puts one of her father’s searing love letters to Marilyn up on screen, reading: “So be my love as you surely are. I think I shall be less furiously jealous when we have made a life together. It is just that I believe that I should really die if I ever lost you. It is as though we were born the same morning when no other life existed on this earth. Love, Art.”

I ask Rebecca Miller if, as a filmmaker, she fathoms why Monroe continues to burn so bright.

“I think she came to represent something, like a patron saint of vulnerability or something,” she says, sipping an iced cappuccino. “There was something about her orphanhood that became in itself its own kind of mythic thing.” Monroe used to tell Miller how to recognise orphans in the crowd by the look in their eyes. Miller called Monroe “a poet on a street corner trying to recite to a crowd pulling at her clothes”.

The romance that began with such passion devoured itself. “He was really, really worn down,” his daughter says. “He hadn’t gotten any work done for a long time, and this was a man who completely identified himself as a writer. And that had been put away, barring The Misfits, which was itself excruciating. But I think she had had it, too. They were not matched. They tried and they just bungled it.

“She was the rose and he was definitely the gardener. But he’s more of a rose and he needed a gardener. People can only play the other part for so long.”

Miller says that eventually her dad realised he could not rescue the eternal orphan.

“You can’t really save someone,” Miller says. “You have to acknowledge that you’re you and I’m me, and your powers don’t extend to being a saviour. My impression is for whatever reason, I don’t know exactly, but she saw death was luring her for a long, long time, and I think that had to be her end point.”

The director originally put in Monroe’s pregnancy during Some Like It Hot, and her subsequent miscarriage, but then cut it. “We had a version where we see her going into the hospital,” she says, “but it’s that line of ‘what’s gossip and what’s getting to the meat of the matter?’”

I tell Miller that I have always had a dim view of her father’s treatment of Marilyn: because of his play After the Fall, about a Jewish intellectual in New York married to a needy show business idol who commits suicide, which he at first denied was even about Marilyn; and also because he crushed her during their marriage by leaving an open journal for her to find, with an entry about how she had disappointed him and embarrassed him in front of his brainy peers.

“I guess I have always been deeply terrified to really be someone’s wife since I know from life one cannot love another, ever, really,” Monroe wrote in her own journal in response.

“Maybe he did it unconsciously,” Miller says about her father leaving out his journal. “But you know what? The unconscious, you never know.” When she was still single, Morath happened to be working on the set of The Misfits for her photo agency, Magnum, and took some haunting pictures of the luminous blonde with the darkness inside.

“My mother was always very sweet about Marilyn,” Miller says. “She really liked her. Someone asked her how the marriage between Marilyn and my father was and my mom was like: ‘Oh, very happy. They seemed very happy.’ Because she wasn’t paying attention.”

About a year after his split from Monroe, Miller began dating Morath. “I am discouraged with myself, my rootlessness,” he wrote to her. “And ashamed too. I can’t talk to anyone but you about so many things. I feel haunted sometimes by the question of whether anything, any feeling, is eternal.”

If Miller had to summon her nerve to deal with the lusty and sorrowful side of her father that bubbled up with Marilyn, she also had to summon her nerve to deal with the most disturbing part of the documentary: the institutionalisation of her younger brother, Daniel, who was born in 1966 with Down’s syndrome.

She was asked to make the film in the mid-Nineties, but demurred because her parents were alive and she had not yet discussed her brother in interviews.

“I didn’t really know how to approach it,” she says. “Because it was a delicate subject for them and it was very personal and they were very private people. And it was a tender point for my mother, especially, and I felt very protective over that. But I also felt a filmmaker’s need to be honest. And I felt, if I’m doing this portrait, I’m going to have to do it. And as I say in the film, my father did offer to do an interview.”

He died in 2005, at 89, before that was accomplished.

It would have been revealing. The playwright known as the moralist of the century for his work and his brave refusal (backed by Monroe) to name names during the McCarthy era, the playwright who focused on fathers and sons, ended up virtually wiping his own son out of his life; Daniel was not mentioned in Arthur Miller’s memoir, Timebends, nor in his obituary in The New York Times. He was also not cited in Morath’s Times obituary.

In the film, Rebecca Miller shows her father’s journal entry from 1968: “As the nurse was dressing Daniel in the hospital, preparing him for our journey to the institution, I turned to examine him – with some difficulty. In a few seconds I found myself, not doubting the doctor’s conclusions, but feeling a welling up of love for him. I dared not touch him, lest I end by taking him home, and I wept.”

If she had done the interview, Rebecca Miller says, she thinks her father would have said this: “That they were advised to do it. That he believed that it was the right thing for our family. It’s a subject that was just hard to broach in my family. And when you’re raised like that, it’s not easy to just overcome that right away.”

A 2007 Vanity Fair article suggested that Daniel had basically been abandoned in an “understaffed and overcrowded” facility in Connecticut, with his father rarely visiting.

“I think the Vanity Fair article was written in a spirit of malice,” Rebecca Miller says. “They made it seem like he never saw him, which wasn’t true. He did see him. It’s just that it wasn’t, perhaps wasn’t, enough. But you also have to put things in a little bit of historic perspective. There were other families who put their Down’s syndrome children in institutions. I don’t know. It’s a mystery. And really, finally, in the film, I was ultimately honest with my own limitations and where my knowledge ends. I don’t know exactly what transpired between those people because they never told me. All I know is what my relationship is with my brother, which is great.”

Encouraged by her husband, Day-Lewis, Miller incorporated her brother into her life.

“I started seeing him much more when I was in my 20s, actually late 20s, to be honest, and even more so once I started to have a family,” she says, adding about her husband: “Daniel was in my life, my children were in my life and I was sort of free to create new rules and another, different kind of life.” Her husband, she says, “breathed fresh life” into her relationship with her brother.

She says her brother, who is said to resemble his father, is “hugely happy” now. He works; has participated in the Special Olympics six times, for biking; and lives with a family that has become “like a second family” and that “has a wonderful social life”, she says.

In her father’s will, she says, his money “was divided by four”.

“It’s one of those things where you can talk and talk and talk, but somehow you don’t get any closer to the truth,” she says, her eyes filling with tears.

Rebecca Miller’s work has been called the “feminist, non-creepy” version of Woody Allen. Ethan Hawke says that being directed by Miller is “like being directed by Annie Hall”.

“Look, this is a difficult subject,” she says of Allen. “What he does inside a frame, he’s moving and he’s moving people around within it. He’s a great artist in that sense. As for the rest of it, it’s a debate. You know, my husband won’t go to see any Wagner operas because he was an antisemite, right? If you only appreciate artists who have been good people, who’s going to be left for us to appreciate? And I do think that I can’t unlearn what I learned from Woody Allen.”

Miller, who has mentored Greta Gerwig (and cast her in 2015’s Maggie’s Plan) and other women who want to be directors, notes about women in Hollywood: “We have to let go of that specialness, of the privilege of being the only woman. Which is a heady thing. But we do have to kind of let go and reach a hand out and pull someone up. Each time a woman makes a successful film, like Greta’s, that is fantastic for all of us.”

She says: “What I worry about with the #MeToo thing is that women are getting addicted to the victim’s role. And that’s not going to get us anywhere in the end, right? Maybe what I worry about is, it’ll kind of, in some weird way, put the screws on and make us all really afraid of sex. And that somehow, it’ll end up backfiring for women. Somehow, we’ll end up with the short end of the stick.”

I ask if her husband’s legendary intensity preparing for his roles (he made her a grey wool dress during a yearlong apprenticeship preparing for his role in Phantom Thread) has ever been hard for her. “You have to do what you have to do,” she says. “Everyone has a different process. The main thing is that everyone respects each other and are fundamentally kind to each other. But he’s very kind, so that’s not a problem.”

She says she told him, when she was pregnant with their first child while he was making Gangs of New York, that he could no longer bring his characters home.

“I was just like, ‘That’s not going to happen,’” she recalls, smiling. “It’s good to at least maintain one personality for your child.”

So, I wonder, that means he never made love to you as Abraham Lincoln?

“That would have been kind of cool,” she says. “But no.”

I tell Miller it’s hard to imagine Day-Lewis lightening up.

She says she visited her husband at their home in Ireland recently. “And we went and got hot whiskeys in a pub in Ireland,” she recalls. “And we walked up a mountain and then we got our hot whiskeys and then we got our scones with cream. That’s the kind of thing of just simplicity and fun.”

She declines to discuss his retirement news, saying, “it’s his thing”, but notes that he is producing a project with her company. She says she’ll be the breadwinner for now, but who knows? He could go back to cobbling. The family spent several years living in Florence while he was working as a shoemaker.

As we get ready to leave, I ask Miller to do her party trick, which is drawing with her eyes closed, or aimed up at the ceiling.

She draws a picture called “A Woman Who Wants an Interview to End”.

It’s very convincing.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments