Raymond Byrd: After decades of silence, how one man is seeking justice for the last lynching in Virginia

An open discussion about lynching, one of the darkest aspects of America’s history, is virtually taboo – but now John Johnson is breaking the silence to tell the story of Raymond Byrd. Stephanie McCrummen reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was cold and snowing, but John Johnson had an appointment to keep. He wasn’t going to let the weather stop him, or the worsening cough he’d been ignoring the past week. He put on his black fedora and drove across town to see a friend.

“John, come on in,” she said, and after they settled at her dining room table, she handed him a piece of paper with the names of 12 people, all of them long dead. He squinted at them through his glasses.

It had been three weeks since Virginia governor Ralph Northam pledged to embark on a racial “reconciliation tour” after apologising for a photo that appeared on his personal medical school yearbook page, showing one person in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan outfit. “A forgiveness tour,” is what John called it. He was an 80-year-old African American man, a retired engineer who had calculated that he had six to eight years left on Earth to pursue his own version of racial reconciliation in his corner of southwestern Virginia, which was why he was at the home of a white woman named Beverly Repass Hoch, looking at the names she had written out.

“One, two, three, four, five, six – six of these names I’ve heard of, Bev,” John said, putting marks next to each one. “The rest I haven’t.”

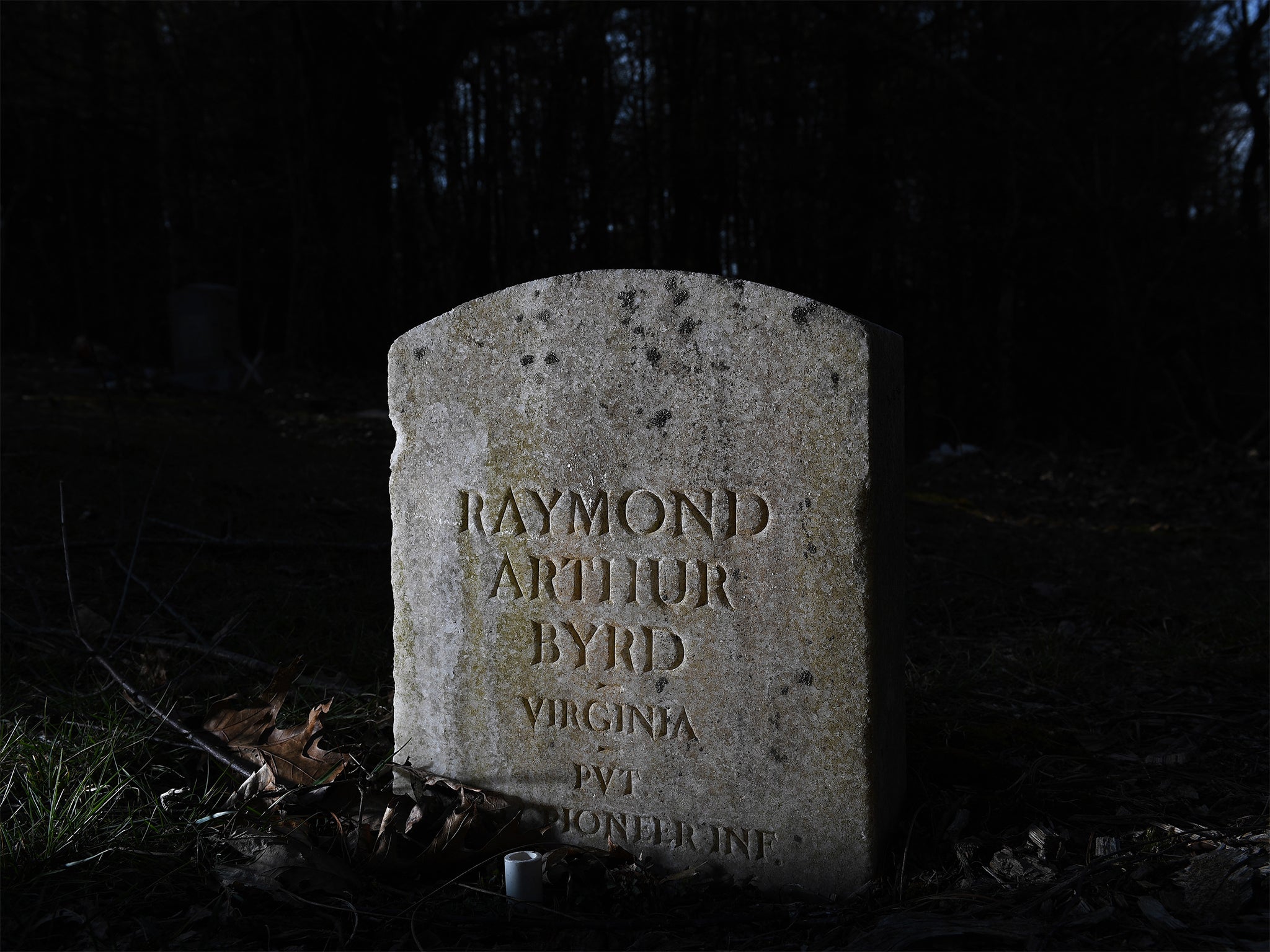

For 30 years, he had been collecting every detail he could about the August 1926 lynching of a black man named Raymond Byrd by a white mob in Wytheville, western Virginia. The lynching was one of more than 4,000 documented in southern US states between 1877 and 1950, killings intended to terrorise black populations and reinforce white supremacy, and whose perpetrators – while known to locals – were almost never convicted or even named, a tradition of secrecy that carried on in Wytheville.

What John wanted was to unearth them. He wanted the names of everyone involved – all of them – and now he had more from Beverly, one of whom she acknowledged had been part of her family. She had some other things to tell John, too. But first she asked for an assurance people were always asking him for, which was to keep the names to himself. He promised.

“Go on,” John said. “I’m listening.”

* * *

It was by most accounts the last documented lynching in Virginia, the first details of which were reported in a three-paragraph story in the Wytheville paper, above the weather and the social column.

“Raymond Byrd, coloured, who was in Wytheville jail charged with a statutory offence against a white woman, pending a hearing, was killed Saturday night between one and two o’clock by a mob of possibly 50 persons,” the article began. “The negro was shot in his cell and the body taken away by the mob. The body was left hanging to a tree about one mile west of the St Paul’s church.”

Dozens of Virginia reporters who happened to be gathered for an event in Wytheville picked up the story, and soon, editorials around the state and beyond were condemning the “crime of collective bestiality” and the failure of Wytheville authorities to identify those in the mob.

It amounted to an embarrassment to the governor at the time, a staunch segregationist coincidentally named Harry F Byrd Sr, who had been trying to attract business to Virginia. He finally sent investigators to Wytheville, who summoned more than 70 witnesses, yielding mostly silence.

“Futile Attempt is Made to Discover Guilty Persons in Virginia Outrage,” read one headline.

“Talks With Witnesses Indicate Majority Know Nothing as to Identity of Mobmen,” read another.

A lone white man who gave a drunken confession was eventually tried and swiftly acquitted by an all-white jury. The state legislature passed an anti-lynching law in 1928, the same year the governor declared: “Virginia owes white supremacy to the Democratic Party.” And that was the official end of it.

In Wytheville, a railroad town of stately homes and white-columned churches, the local newspaper returned to promoting tourism and a new hotel. Many black families fled the area, leaving behind houses and property, and joining the vast exodus of African-Americans escaping violence in the south for northern cities. Wytheville, already roughly 90 percent white, became even whiter. The code of secrecy protecting the lynch mob prevailed. And in 1938, John Johnson was born.

“Stay in your place, that was the rule,” he said, remembering how life was. “You get out of your place, you’re in trouble.”

Certain memories stuck with him. He once saw a cross burning on a neighbour’s lawn. He remembered a mayor who did a summer minstrel show wearing striped pants, a plaid blazer and blackface. He remembered the white men who always sat in front of a certain store downtown, who would rub his head “like a dog” when he passed, or use rubber bands to shoot at him with fence nails. He remembered the look in their eyes that he took to mean: “What are you doing here, n****r?”

He got called the name by a bunkmate after he joined the Army in 1961, and by a little white girl in a store the day he returned home. He got called it by his white co-workers when he integrated a machine shop in the 1970s, and after he was promoted to management in the 1980s, which was the period in his life when he took up the hobby of metal detecting to relieve stress.

He’d go out into fields around Wythe County and find old coins, and one day, he turned up an odd-shaped piece of brass, about eight inches long, tapered with a hole on the end. He showed it to his father, who told him that it was the end of a lash for whipping slaves. And that was when John became curious about the history of African-Americans in Wythe County, including a story he had grown up overhearing his father tell, about a lynching.

When he asked him about it as an adult, his father told him that he had been among a group of men guarding the Wythe County jail the night a mob came and killed a man named Raymond Byrd, and John became consumed with finding out the full story.

“I wanted to know what happened, why it happened, who was involved, the whole detail about it,” he said.

I’m the keeper of the secret. I’ve got the names, and I don’t really right now know what to do with them before I die. And I’ve got to do something with them before I die

He talked to his father and began trying to find others who had memories of the night. He found other men who guarded the jail. He found a daughter of Raymond Byrd still living in Wytheville. Soon, informal conversations became interviews that he began taping with a small cassette recorder.

“Cut that thing off,” more than one person told him.

“You don’t need to know about that,” another African-American man said.

“Pull those shades down – I don’t want white people to know you and I are talking,” another person said, afraid those people might throw bricks through her window.

In the quiet of so many afternoons and evenings over decades, she and others would talk and mention a person, or a detail, or a feeling that had lingered all these years later, unresolved, and soon John had files full of notes, documents, photos and transcripts, and a growing list of names. And now he was 80 years old.

“I’m the keeper of the secret,” he said one afternoon. “I’ve got the names, and I don’t really right now know what to do with them before I die. And I’ve got to do something with them before I die.”

* * *

He was well known around Wythe County. He had saved from ruin the first local school for African-American children, built in 1882, and turned it into the Wytheville Training School Cultural Centre. He had written a book on records of freed slaves. The Rotary Club named him a fellow. His name was etched on a town monument of “Honoured Citizens”. If anyone wanted to know about African-American teachers, or businessmen, or soldiers, or genealogy in Wythe County, they called John Johnson.

“Hi John, you sleeping better?” said the president of the local genealogical association when he stopped by one day. John often worked there in the library-like room full of records and lists of prominent Virginians such as the “First Families of Wythe County”, who were really the first white families of Wythe County, some of whose last names were on his secret list.

“Trying to,” John said, stifling the cough.

He stopped by the new Edith Bolling Wilson Museum downtown, a redbrick building with an American flag out front that was the restored childhood home of the first lady, President Woodrow Wilson’s second wife.

“Hi John, how’re you doing?” said the woman who helped run it.

“Doing fine,” said John, who looked around at the old mantel clocks and family china that tourists came to see when they wanted to see some Virginia history, then walked outside and looked across the street, where the white men who shot him with the fence nails used to loiter.

“Every time I come down this street, I remember that,” he said, reaching around to feel his back.

He drove through town, and when people saw his fedora they waved through their windshields. He passed by old neighbourhoods with picket fences, and newer subdivisions of sprawling yards, and everywhere he went he could point out houses where black families lived next to whites.

“Black people can live anywhere now,” he said.

He could not say that things had not improved in Wytheville, to a point. There was an earnest politeness that governed conversations, though his experience with certain people had taught him that politeness required silence about the lynching.

“I know if I start to say something they’ll tell me to shut the hell up,” he said.

Soon, he arrived home, where he had converted his dining room into an office full of files of all the hushed voices and stories of African-Americans in Wytheville. He worked most nights until 2am, not just on the lynching but other projects, such as documenting every single grave in 54 African-American cemeteries in Wythe County, including the one under a trailer park where his great-great-grandfather was buried. But his abiding interest was in resurrecting the story of Raymond Byrd.

In one file were military records showing Byrd was a World War I veteran who had served with the 807th Pioneer Infantry in France.

In another were the 1926 newspaper accounts describing how Byrd, whose name was sometimes spelled Bird, had worked just outside Wytheville for a white farmer named Grover Grubb, who had a daughter named Minnie, who became pregnant with Raymond Byrd’s child. He had accounts of how Minnie gave birth to the child, a girl, and how after that, Grubb accused Byrd of rape. He had later accounts stating that Minnie refused to say that Byrd raped her.

In another file was the transcript of John’s interview with his 94-year-old uncle, who said that in the days after the baby was born but before Byrd was arrested, Byrd had brought the infant to his house:

“He couldn’ find no body to take her [pause] and he was going to take her to the woods. So I guess he was going to kill her [pause] I reckon. And so my wife was so tender hearted, and everything you know, and said she would take it if they couldn’ find somebody to keep it.”

There was a statement from the sheriff describing how deputies fired a shot on a ridge to signal when they had arrested Byrd, and how an armed mob was assembling at Grubb’s farm. There was a description of the screen door that was all that separated Byrd from the mob when they came for him at the Wythe County jail, and how some in the mob wore disguises. There were descriptions of what was done to Byrd in the jail, how he was shot in the chest and his head was battered with clubs and rifle butts. And how after that, his body was dragged a distance through town behind a Model T Ford, then driven out near Grubb’s farm and hung from a tree before a crowd of possibly hundreds.

There was Byrd’s death certificate, listing his date of birth as 2 April, his age as “about 31,” his father’s name, Steven Byrd, and the cause of death: “By being killed by mob in Wytheville Jail. No doctor summoned.”

There was an unsmiling, black-and-white photo of an African-American man who had witnessed some part of all that, who was in his eighties when John tried to interview him.

“He looked straight at me,” John recalled. “He said: ‘Son, I’m not going to talk to you about it.’ He said: ‘You don’t need to know nothing about that.’ I was looking at him. I said: ‘Damn, are you that frightened? Are you that scared?’ I said: ‘Does it still bother you?’”

There was a photo of Raymond Byrd’s wife, Tennessee Hawkins, with whom he had three daughters. There was a recording of one of those daughters, who was in her seventies when John sat in her living room and pulled down the blinds.

She said: “The morning we found out that my father had been hung, we children – my mother didn’t have anything to feed us for breakfast but cold beans.”

She said: “Them old white people, I hate ’em all. I just don’t want ’em around me. I don’t trust ’em. The only thing I think about when I see ’em is bringing blood.”

Over the years, people had also given him things, always in confidence. A waitress at Shoney’s gave him a photo of Minnie Grubb, who lived out most of her life in Ohio, where her daughter eventually joined her. A co-worker once gave him a photo of another lynching in a neighbouring town. One day an elderly white man called John on the phone and asked him to come to his house on the outskirts of Wytheville.

When John arrived, the man shook his hand, brought him down into the basement and pulled a wardrobe away from a wall, where there was a piece of rope hanging from a nail. He told John that it was from the rope that had tied Raymond Byrd’s hands, and that he thought John should have it, and John thanked him and drove home with it on his passenger seat, zipped in a plastic bag, wondering whether it really was what the man said it was, or just the man’s way of apologising.

He kept it inside a safe where he kept his guns, near the file where he kept the names that people had given him when the tape recorder was cut off.

All of it was locked up inside his white-sided house on a grassy corner of Wytheville, where the name Raymond Byrd was nowhere to be found, not in any museum, not on any plaque, not in the newly added “African American loop” in the Wytheville walking tour guide. The killing of Raymond Byrd had been spoken of publicly in Wytheville only once, in 1993.

A historian who had written an academic paper on the lynching had presented his research at a local symposium, where he publicly thanked John for his contribution to the work. The Wytheville newspaper published a story on the talk, and not long after that, John remembered, he got a phone call from a woman who said she was a descendant of Grover Grubb, and began saying that there was no good reason to bring up the lynching, and how much pain it caused her family, and John interrupted.

He told her that if she wanted to be upset, she should talk to the descendants of Raymond Byrd. And then he hung up.

* * *

And that was how it had been going in Wytheville, where one evening John got together with eight people for the monthly meeting of a civic group called Concerned Citizens. The group had formed to talk about a range of local issues including hiring practices and problems in the schools, discussions that often wound up being about race, which was the case on this night, as the conversation turned to Ralph Northam.

“I grew up with blackface,” said John, one of three black people sitting at the table. “Didn’t surprise me. And when nothing surprises you, it doesn’t bother you.”

“I’m in line with him,” said a white woman named Maxine Dellinger, who was one of six whites there. “I’m 77 years old and I was born in that time period and I wasn’t aware of it. It’s an educational process for us.”

“I think it’s interesting there were some people who really didn’t know blackface was offensive,” said a local pastor named Cindy Privette. “So, I think it brings up the issue of white privilege in that we as white people need to listen, so we can know what is offensive. For me, it almost puts a barrier between me and a person of colour because I’m afraid I will be offensive, unknowingly.”

“I hear that so often,” began Eric Simmons, who was black. “The reason we keep revisiting this same topic is because we didn’t have the conversation before. As African-American people, I think we shuffled around certain issues because we didn’t want to offend white folks. White folks didn’t want to offend black folks. But we need to talk about those old issues and get on some solid ground. Right now, we’re not on any solid ground.”

John listened. He was a mentor to Eric, but had only told him so much about the lynching, because he was worried about upsetting him. Eric turned to a white woman, who was a psychologist.

“For people to get over a tragedy, most times you ask questions to take them back to where that tragedy happened, right?” he said. “So, as far as black people are concerned, when in the world have we ever sought counselling for all the things that happened to us?”

Eric had been thinking lately about all the things that had happened in his own life, remembering the white kids who stuck him with push pins when he was one of the few black kids on the school bus, and the first time he got called the n-word. He had been trying to understand where all that came from. He had read a book called Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust, as well as The Autobiography of Malcolm X and others about all the things he had never learned about American history.

“People say: ‘Oh, slavery, you weren’t even present,’” he said. “But when you grow up with generations and generations of stories, or when you see black people who won’t even look white people in the face, that affects you. It sure does.”

After a while, a white woman named Linda DiYorio interjected.

A boy had come running inside, screaming that there was a body hanging from a tree in the nearby woods

“I get all this about history,” she began. “I get it. And I know very little about it – I’m sorry, just what I had in high school and all. And I think I’ve said this many times in this room. But we need to figure out today, and the future too.”

She was involved in Democratic Party politics, and had tried to encourage Eric and other African-Americans to run for office or apply for local boards. She wanted to figure out how to increase black voter turnout, which was often low in Wythe County.

“What I’m saying,” Eric continued, “is if we’re not going to have those conversations, this ain’t ever going to go away. Doesn’t matter how many times you vote. We’ve been voting all this time...”

“No,” interrupted Linda. “No, you haven’t. Look at the statistics.”

“Look at the people who lost their lives to vote,” Eric said.

“Honey, I’m not talking about that period,” said Linda. “I’m talking about what can we do today. I hear what you’re saying about the history. But I’m just saying, I can’t do anything about the history. Other than read it, and try to understand it.”

“Then read it,” Eric said sharply. “And try to understand it.”

“I’m not going to say anything else,” said Linda, and soon the meeting was over.

“So,” John said later. “These are the some of the discussions we have.”

A few days after that, he drove over to the home of his friend Beverly to have another conversation.

They had known each other since the 1980s, when they met at an American Civil War re-enactment that John had organised. They recognised their mutual interest in local history, and as they kept talking, Beverly asked John whether he had ever heard about the lynching. John decided to take a chance and told her he had, and over the years, a friendship had developed in which they met from time to time to talk about some of what they were finding out, she from talking to white people, he from talking to African-Americans.

Beverly, who was 77 now, had told John that she had grown up hearing her father tell a story from his childhood about a Sunday morning when he was in St Paul Lutheran Church, and a boy had come running inside, screaming that there was a body hanging from a tree in the nearby woods. She had told John about the man who recalled his father taking his Model T Ford to a creek after the lynching, and washing out what he assumed was blood. She had told him about the man who remembered seeing his father lay a gun on the kitchen table and saying: “It’s over.” Now she was telling John that she had gone through her interviews and compiled a list of the people named as being in the lynch mob, 12 in all, one of whom had been a relative.

She slid the paper across the dining room table.

John looked at the names, and focused in on one of them.

“This name rings a bell because it’s the same as the man who gave me the rope,” he said.

He had told Beverly about the rope, but he had not told her everything. He had not told her about what Byrd’s daughter had said about her hatred of white people, or about the terror he could feel from others, or the fear he still felt at times himself being a black man in a part of Virginia where white men had gone on a gun-buying spree after the election of Barack Obama, and not far away, white supremacists had rallied after the election of Donald Trump as US president.

Until now, he had not told Beverly what had been weighing on his mind lately. “I’m trying to decide about all my research – you know, what’s going to happen to it,” he began.

“I’ve been thinking about that too, lately. Maybe putting it in something more formal – not a publication, John,” Beverly said. “I’ve got relatives all over the county, and I don’t want to hurt them. We’re not up to making people feel bad about their ancestors.”

“No,” said John, who had heard this from Beverly before.

“I feel very connected to them and wouldn’t want them to be negative toward me,” she continued, not elaborating, as she would later, that she’d “resent it” if anyone asked her to bear responsibility for what a relative had done because “I’m not guilty of any of that”, and “nobody today is guilty of that”, and that while she was in favour of museums and Civil War memorials, she did not think the lynching needed a memorial, or a place in a museum, or a public reckoning involving names because “people would be very angry about it – I can feel it”.

And that was why, she told John now, she was planning to give her research to the Wytheville genealogical association, where it probably would go in a box, in an archive, “for future generations”.

“I don’t know, John, from your perspective, if that’s how you feel about it,” she said.

He had been looking at the names while she was talking.

“I haven’t decided,” he said.

He did not elaborate, as he would later, that his own reasons for keeping the names secret all these years had to do with fearing for the actual safety of the African-Americans who had trusted him with their stories, and for that matter, his own. As he’d said once: “See, I’m not a white guy with these names. I’m a black guy with these names.” He did not elaborate about how he felt Wytheville was “erasing an entire family” of people by refusing to acknowledge the lynching, and how tired he was hearing people talk about “feelings” when they really meant the feelings of white families trying to preserve reputations.

“I want the history out there,” he said now. “I want people to be prosecuted, but right now it’s beyond the time. I wish there would be some way that you could get those descendants still living to sit down at the table and say, you know, we’re sorry for what happened. And be honest about it. And don’t go home and say: ‘Well, I didn’t have to say that to the n*****s but I did.’ I just want them to say: ‘I’m sorry for what happened, for what my grandfather or great-grandfather did.’ Don’t keep hiding. Tell people you know it. Admit it. I want them to admit it.”

Beverly was quiet for a moment.

“That’s not realistic, John,” she said.

“No, it’s not,” he said. “It’ll never happen.”

“No,” said Beverly, and soon John glanced at his watch.

“Well, it’s getting to be 3.30,” he said, standing up to leave.

He looked around, and complimented Beverly on the telescope she had in a front sitting room.

“Who likes to look at the stars?” he asked, and the polite conversation carried on a few minutes more as John put the list of names in his pocket and headed to his car.

* * *

He went home. He added the new names to his file. And he kept thinking about what he should do in a place where descendants lived all around him, including in a small white house on a hill outside town, where the great-grandson of Grover Grubb sat on his couch one afternoon, remembering a time when he had to decide what he should do.

Ed Atwell had a long white beard, family photos on the walls and books about Gandhi on a shelf. Somewhere, he had the 1993 academic article about the lynching, which was how he had learned the full story about the great-grandfather he dimly recalled as a quiet man who gave him old tobacco pouches he used for marbles. He recalled how not long after the article came out, he had gotten an email from a descendant of Raymond Byrd, who wanted to talk.

“I just told ’em, not now,” he recalled. “I just chose not to do it. What could I say? What could I say or do? Say I acknowledge it and I’m sorry it happened? I am sorry it happened. I hate that it happened. I was kin to the people.” He paused for a moment. “All I get out of it mostly is a great sadness.”

That was the Wytheville that John had come to know, a place of willful avoidance and feelings unresolved, where one day he decided to take a drive.

“Right here is where the jail sat,” he said, pointing to a low stone wall and a grassy field that was now a park. “That’s where they shot him and beat him.”

He was driving along Monroe Street in downtown Wytheville.

“They put him behind the car and drug him all along here,” he said, driving one block, then another, and another. “Back then, it might have been dirt.”

He passed an insurance agency, a parking lot, some old magnolia and oak trees and houses with front porches and wondered who might have been watching. Another block.

“He’s being dragged,” he said, imagining.

He turned right on Lee Street, passed a Pizza Hut and Dollar Store and continued several hundred yards more to a curve in the road where there was now a Dodge dealership. He pulled over.

“Right here is where they stopped and put the body in the back,” John said. “They put the body in the rumble seat.”

He stayed there for a moment, then pulled back onto the road and kept going.

“From here, they drove to St Paul’s church,” he said, driving out of Wytheville, out on a two-lane road through sweeps of green fields and the blue green ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, on past old barns and houses and farms until 10 minutes had passed. He kept coughing.

“See?” he said. “They brought that man all the way up here to hang him. Can you believe that?”

He kept going. A few minutes ahead, he could see the white steeple of St Paul’s jutting into the blue sky, and now John turned left onto the narrow road heading toward it.

“They drove that man up this road, over by this church,” he said.

He kept going. He drove past the church. He drove past the church cemetery full of headstones including one chiseled with the name Grover Grubb.

“You see, they point the dead to the east,” John said. “That’s because Christ is coming the second time to the east. They point to the east to see the coming of Christ.”

He turned right at the end of the cemetery. He continued up a slight hill.

“When I drive this road now, I get a certain feeling,” John said.

He drove a few hundred yards more, higher and a bit higher, and now he stopped.

“It was in those woods,” he said.

There was a stand of trees.

John squinted into the shaded tangle of limbs and trunks, and now he was pointing.

“Can you see it?” he said.

He pointed to all that was left, the stump of a tree that he believed to be the one that had held the body of Raymond Byrd. He imagined the white crowd looking it. He imagined them mutilating it. And now he told the story he told himself about why the tree had been cut down, and why, even 93 years later, there was no reconciliation.

“They are ashamed,” he said.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments