The priest who turned his back on the church – for love

After years of training and conditioning – brainwashing, if you like – Kevin Hartley walked away from a life of teaching Catholicism for the ultimate sanctity: love of a good woman

Marriage was the last thing in my mind as I knelt in the chapel of the English College, Lisbon, in June 1962. My family and a bunch of friends had come all the way from England for my ordination. The palms of my hands were anointed with oil, the bishop had laid his hands on my head, I was a priest forever.

The Lisbon College had been founded in the 17th century to train English men to become priests who would return in secret to minister (at the risk of their lives) to the scattered Catholics of their home country, and I was their inheritor. I wouldn’t be risking my neck to go back to England, but I was prepared to serve for the rest of my life wherever my bishop required me.

Apart from brief visits, I’d been away from England for six years. Within a couple of weeks of my arrival I was plunged into the challenge of parochial duties in a parish in south Manchester. To be called “Father” by people old enough to be my grandparents didn’t seem odd, though I could be defensive when someone challenged me, a grown man of 24 and a priest, on some point of morals. I still blush to think of the time I had a set-to with a couple about their use of the pill. It started quite innocently, with them telling me they’d given up going to church. Then as the reason became apparent – they were using the pill because it was out of the question they should have more children – I found myself arguing forcefully how artificial contraception was contrary to Church teaching because it was a deliberate thwarting of the natural function of sex. I was so adamant, so sure of myself, so wrong-headed. We parted angrily and I never saw them again. But that was how we had been trained; the Church had the right answers and if someone couldn’t be convinced, that was their lookout.

On the whole, people seemed to accept me as they found me; they, like me, had bought into the traditional image of the priest as the leader, the authority, in matters to do with the Catholic faith and, secure in my status, I was able to relate on friendly, not intimate, terms with all the different people I encountered in my parish. I’m not saying I was brilliant at what I was doing but it was satisfying. It was good to visit happily married families, to sympathise with those in difficulties – “Fred’s away, Father” meant a woman had been left on her own to look after her children while her partner was in Strangeways – but there was always my own corner to retreat to in the presbytery at the end of the day.

Why does it take six years to train a Catholic priest? What he needs to know in order to function could be fitted into a year, a couple of years at the most; six years is for conditioning, brainwashing if you like, to ensure obedience to the Church’s teaching and, inevitably, to inculcate acceptance of celibacy. Some people find the idea of a celibate male unimaginable, unnatural. Didn’t you feel frustrated, I’ve been asked, when you saw attractive women who were beyond your reach? You might as well ask a member of the SAS if he envies the easy life of civilians. You’d probably get a short, unprintable answer.

It’s perhaps an unfair comparison but the point I’m making is that those years of conditioning formed the life of the priest. If the soldier can’t accept that ultimately his job is to kill or be killed, he’s declared unfit for duty. If the Catholic priest can’t accept that celibacy is a way of life dedicated to the greater good of his parishioners, he’s regarded by his superiors as spoiled goods, a waste of space. That at least was the attitude in former years.

Of course I noticed pretty girls. In college, the joke had been, “just because you’re on a diet it doesn’t mean you can’t look at the menu”. But like other priests I exercised prudence in the company of women. I’d been warned by senior clergy about predatory females, women who would see the dog collar as a bit of a challenge and sure enough there were some in the parish who liked to flirt, and not always single girls. I was naive enough to be flattered by their attention but secure in my celibate armour I managed to keep them at arm’s length.

One of my duties was to act as chaplain to the nearby Catholic secondary school where Miss Maben Maclean, a newly appointed PE teacher, caught my eye mainly because she was nearer to my own age and, perhaps because she wasn’t a Catholic, she didn’t treat me with the same mixture of deference and reserve I got from the rest of the staff.

The school organised a trip to Belgium one summer holiday. I was invited to join 50 Manchester kids on the loose and a handful of staff seemingly more intent on getting drunk than looking after their charges. For a week Maben and I found ourselves dealing with drunken teenagers, trying to keep vulnerable kids out of harm. That gave us a special bond, it was good to have a close female friend, nothing more than that. I don’t think we ever kissed and marriage certainly wasn’t in my mind. But a firm friendship had been formed, out of adversity, you might say.

Then Maben announced that she’d had enough of miserable wages and grotty accommodation in Manchester. She was off to join her brother in Canada.

A year or so afterwards I volunteered to teach in a junior seminary in Rwanda on a five-year contract. It wasn’t on any sort of rebound, not even subconsciously; a romantic relationship with Maben never even crossed my mind. I’d had enough of working with an alcoholic parish priest, especially since the Church authorities preferred not to do anything about it. These days one might ask for a transfer to another parish but that wasn’t done in the Sixties; volunteering for missionary work, however, was encouraged and though I didn’t know anything much about Rwanda except that they spoke French and produced exotic postage stamps, it seemed a exciting challenge (it just happens to be also the setting of my next novel).

Five years in a remote part of a very undeveloped African country was quite an experience. I met some interesting people, got a different perspective on the effects of colonialism and learned a lot of French and a little Rwandan.

Maben wrote to me, I wrote to her. She told me about the novelty of being the single teacher in a country school before moving to a high school run by nuns in Midland, Ontario. I described what it was like living a remote African country. She told me about her engagement to a local man and later I had to commiserate with her when she broke it off.

With hindsight I think we may have both been beginning to dream the impossible dream. Certainly I vividly remember a strong sense of resentment when I heard there had been a Papal pronouncement condemning men who abandoned their priesthood for marriage. My first thought was that it was an unwarranted slur on the integrity of people who had come to realise they had no vocation to celibacy, a disciplinary requirement that could be relaxed rather than an essential element of priesthood – as we were to learn much later when the Church began to welcome to the priesthood with open arms married former Anglican clergy, while at the same time officially still declaring the absolute necessity of celibacy.

But looking back, I think there was also a sense of personal fragility. Philip Larkin’s pithy comment on parental influence might well have been applied to to the Church’s training of candidates for ordination. I’d never had any sort of relationship with a girl; from the age of eleven, when I’d expressed a wish to be a priest, I’d been been set apart, culminating in six years in a quasi-monastic environment. Now I thought, when I heard what Pope Paul VI had said, that could be me, that’s what people would think of me if I ever left. I’d heard rare examples of priests abandoning the ministry but didn’t know any of them personally. What would it be like, I wondered, having to leave the security of the priesthood – because it’s about the safest job going, from ordination to the grave. It won’t make you a fortune but you will always be looked after.

I came back from Africa, went on holiday to Toronto. Was I hoping? If so, it was a hope buried deep in the subconscious. Self-deception, if you like. I think most of us are capable of a fair degree of that. Perhaps there was also a chancy element of “what if?” But certainly as I set out there was no definite thought in my mind of leaving the ministry – this was an opportunity to visit a new country and meet up with an old friend. I didn’t know it at the time but later I found out that a nun friend, one of Maben’s work colleagues, had told her, “You’re going to marry him.” So it seems other people could recognise signs I wasn’t aware of. As for Maben, her reply to the nun was that marriage to a priest was impossible! But before the end of the holiday “impossibility” had become something of a certainty. We seemed to make up our minds with almost indecent haste.

All the same, I returned to England in a turmoil. The “what if” had quite suddenly turned into “how do we get through this?” I broached the subject with my parish priest who was amazingly supportive. And then I went to see my bishop. “What would your reaction be if I told you I wanted to get married?” He was quite distressed at the news but seemed to recognise he wasn’t going to get me to change my mind. There followed a couple of difficult interviews with senior clergy, the first question being “When did you realise you had no vocation to be a priest?” My reply, that while I thought I had a vocation to be a priest I knew I had no vocation to be celibate, fell on uncomprehending ears. Eventually they were resigned to me leaving, but I would have to write to the Pope, asking for a dispensation from the vow of celibacy. That was how much I was in thrall to the institution of the Church.

By now I was intellectually prepared for departure but emotionally all at sea. In Catholic eyes, priests were on a pedestal, different from ordinary folk, owed reverence because of their sacred calling. Falling off that pedestal, leaving the ministry, made you a renegade in some good people’s minds because there was a powerful ingrained sense of the priest being bound by a calling from on high. In leaving I was betraying the cause. Was what I doing wrong, a sin? There was a sense of guilt that took a long time, years even, to totally overcome. Guilt is probably the wrong word; I’m sure I was influenced by the way students who decided to leave the seminary were treated – with no announcement, simply an empty place at table and no explanation given either by the departing student or the staff. So I might be forgiven for thinking of quitting the priesthood as something shameful. I was convinced I was doing the right thing for myself but, thin-skinned as I was, I dreaded what others might think of me. The more I found that people accepted what we had done, the less I felt sensitive about the step we had taken.

Eventually permission to leave the ministry was granted, grudgingly I imagine, and with conditions, and I was cut adrift, with no question of financial assistance in recognition of what I’d given the Church. In Catholic teaching priesthood ordination can’t be removed from a person but priestly practice can. Being given permission to leave meant I was, in the jargon, “reduced to the lay state” – I was not allowed to celebrate Mass or administer any of the sacraments (with the exception of hearing someone’s confession in danger of death). I was not allowed to teach in any Catholic institute of higher education. I was also warned that I should not continue living in any area where I was known “for fear of giving scandal”.

Fortunately, perhaps because attitudes were already beginning to change, no one in my immediate family ostracised me. Only one relative, an elderly aunt who lived in Ontario, snubbed me. She was very much an old-school Catholic and never answered the letters I sent her every Christmas. Friends were very much more understanding. If any didn’t approve they certainly never showed it. I think there was even then beginning to be a divergence between the official position of the Church – this man is something of a renegade – and the attitude of (most) clergy and laity. I certainly didn’t have difficulty in finding work teaching in a Catholic school and the parish I live in now is very welcoming, as is the bishop of the diocese. Some years after my marriage I visited my old parish church, to show my children where I used to minister. I happened to meet one of my former parishioners who greeted me warmly with, “Hello Father”, before halting in confusion. My reply, “That’s right, two times a father now”, made us both giggle.

So, in the end we got married in a cold and snowy Greenock (Maben’s home town). Three weeks after our wedding I went down with a mysterious disease which left me in hospital for six weeks. I nearly died but thanks to a conscientious physician who read the small print in his text books I was diagnosed as having a tropical abscess on my liver, a relic from my time in Rwanda. Maben says she was convinced at the time it was God’s punishment for us having married! She’s long since got over that.

Celibacy, the idea of denying oneself a perfectly good way of life in order to be devoted more entirely to the needs of others might be considered a heroic virtue. Imposing it as a matter of discipline is a different matter. Although Jesus wasn’t married (whatever Dan Brown and the like might claim) he certainly seems to have enjoyed the company of married people and he did cure Peter’s wife of some sort of disease.

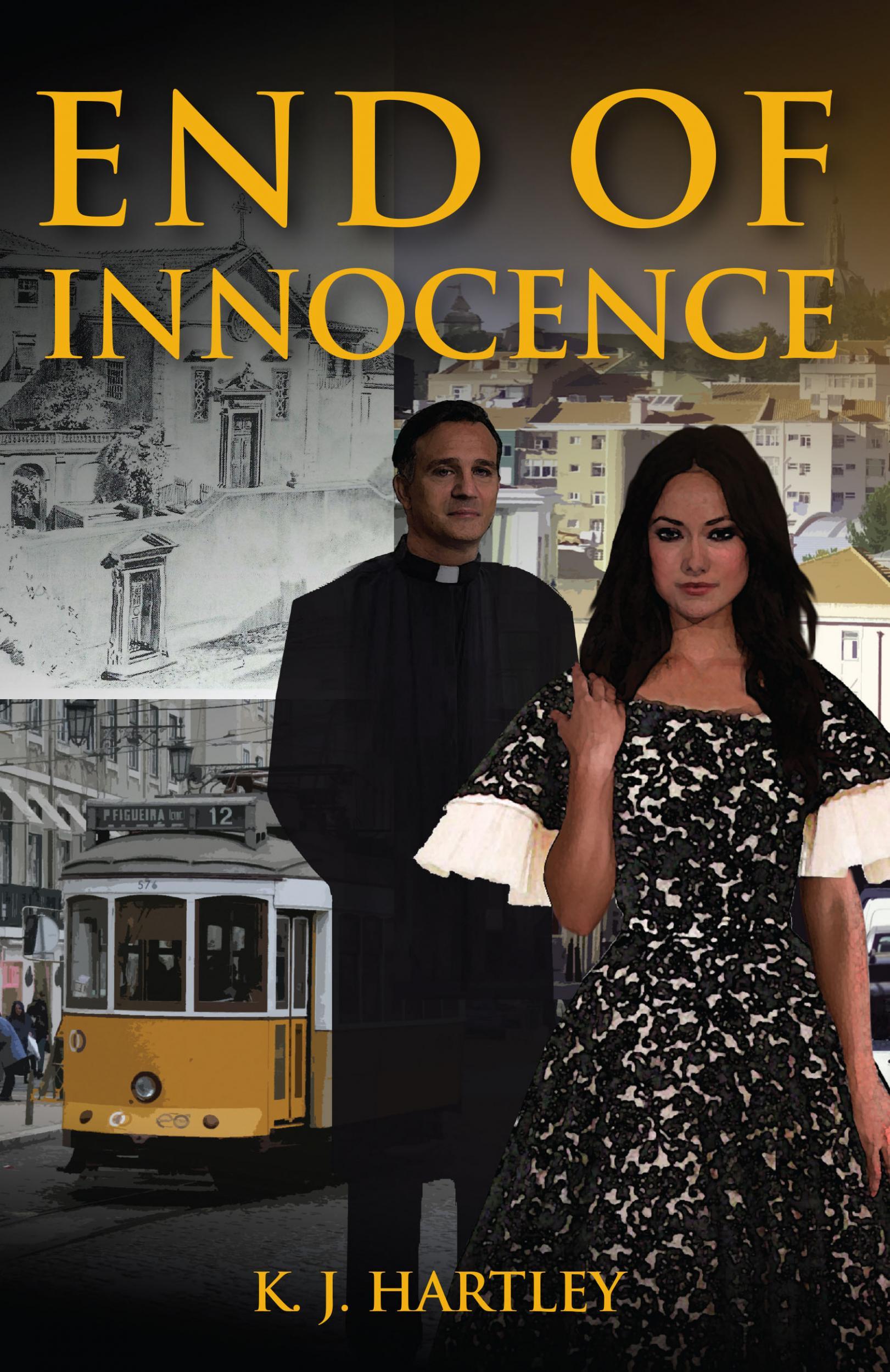

My novel End of Innocence is not overtly autobiographical. The setting – the English College, Lisbon – was chosen mainly because that was the only seminary I was familiar with and the epoch – Lisbon at the début of World War Two – has always fascinated me, a world of espionage and the dictatorship of Salazar. However I can recognise in Michael Harrington’s dilemma something of the confusion and uncertainties I experienced myself. Harrington is the product of his upbringing, intellectually savvy, emotionally naive. The coup de foudre he experiences in meeting the lovely Dona Elisabeta turns his ordered world upside down, as marriage did mine.

End of Innocence is published by Conrad Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks