Paperback writers: Can ‘pop-lit’ give literary classics a run for their money?

In the traditional pantheon of ‘great literature’ there is no room for authors such as Maeve Binchy and Len Deighton, whose rollicking reads meet with mass-market appeal but critical snobbery. Self-confessed history man Robert Fisk questions why their work should suffer in comparison

In the very early 1980s, a most accomplished Irish writer and journalist would sit in her little home in the County Dublin village of Dalkey, hammering away on her first novel. It told the story, starting in the Second World War, of two families and of two young women, one Irish, the other English. Opposite the novelist, on the other side of Sorrento Road, in another little cottage, was a Trinity College Dublin PhD student who was writing his thesis on Irish neutrality in the Second World War. Each night, around 11pm, the novelist and the student would look through the curtains across Sorrento Road from each other to see if the other was still at their desk. If one was still at work, the other would go on writing for another hour.

The novelist was Maeve Binchy. The student was me. And when Maeve published Light a Penny Candle in 1982, she handed me a copy of her book in the middle of the narrow road between our two cottages. “In memory of the long days and nights of typing at windows opposite each other,” she wrote on the first page. Her book was 540 pages long. When I published my thesis under the title In Time of War a year later, it was just over a hundred pages longer. Maeve became a best-selling novelist. Tens of millions of copies of her books have been sold in 37 languages, and they are, as we journos like to say, “a great read”.

They are not “great literature” of course, because they are far too popular and grasp the hearts of too many people. Light a Penny Candle’s theme of love and betrayal – especially betrayal – touched the simple fears of Irish and British women in a chauvinist world moving out of the fear and austerity of war. By strange coincidence, Maeve’s book and my own work on the Second World War had something in common. Elisabeth, Maeve’s principal English heroine – neither of us used “hero” for women – is sent by her parents to neutral Ireland in the war, because it is safe from air raids. A theme of my own work was that in the Second World War, neutral Ireland was not very safe at all; according to an Irish minister, “Eire” was in “a condition of limited warfare” with both Britain and Germany, both of which had plans to invade the newly independent country.

But first I must confess a fear. Having read so much about war – my dad’s First World War, and the Second World War – and then, as a journalist, reported the direct effect on the Middle East and its conflicts, I’m a history man. I don’t read much fiction; except for the “great literature” which my dad and then my schoolteachers and then my first university (Lancaster) insisted upon. I want official records, eyewitness accounts, authentic letters, harsh judgements. On film, I’m interested in real photographs – the newly discovered, the previously unseen, the better – and in genuine documentary footage, not cheap recreations.

Still, I acknowledge the unstoppable power to convince of the cinema which, however “authentic” in its portrayal of war, must inevitably – if it is to reflect events in imaginative form – be treated as a filmic version of a great historical novel. Tolstoy. They made a film of Light a Penny Candle. But how many adaptations of War and Peace for the screen? At least seven. Curled up on my sofa in Beirut, I watched the latest BBC version of a book so vast that my old brown-hatched edition includes a card index, like a miniature telephone directory, of every character. I thought the BBC film contained some awful clichés; until I checked back in my copy of Tolstoy and found that the great master used the very same clichés. Though they were not clichés then.

She listened while he ranted, she listened, still sitting on the upturned drum, while he sobbed. She couldn’t hear what he said into his big blue handkerchief. She waited while the sobbing ended and was replaced by sighs

But was Tolstoy “popular”, in the sense that Maeve remains “popular”; easy to read, little philosophising but devastating in its bitterness? Young Aisling, for example, as she watches her husband Tony descend into alcoholism, is indomitable, though the words she expresses are those of the middle-class village of Dalkey, where Maeve grew up – and where, many years later, we wrote opposite each other’s window every night. “Because you know,” Aisling tells Tony, “how much I like you and love you, and how you’re the one I want, and you’re my Tony… and it’s just ridiculous our pretending that nothing’s wrong…”

There’s a terrifying scene when, earlier in the novel, Aisling’s sister Maureen thieves gifts from the village shops at Christmas so that she can be praised for her generosity by her parents, only to be met by her father’s violence. And when Aisling’s older brother Sean dies – fighting in British uniform in Italy – her mother Eileen has to break the news to her father. “They never touched each other or held each other as she spoke of the telegram… Then she listened. She listened while he ranted, she listened, still sitting on the upturned drum, while he sobbed. She couldn’t hear what he said into his big blue handkerchief. She waited while the sobbing ended and was replaced by sighs.” Eileen had waited four days before she told her husband the news. Maeve’s books are about time.

If it’s not what that pompous old sophist FR Leavis would call a “significant creative achievement”, Light a Penny Candle is a wonderful read – and it sits on my shelves of Irish literature, alongside Seamus Heaney and Shaw and Beckett. Maeve died more than six years ago, but by chance The Gaiety Theatre in Dublin is staging an adaptation of her book in four months’ time. And the theatre’s publicity claims that Maeve Binchy “is one of those rare writers – like Dickens, Wilde, Shaw, Behan – whose work springs from their larger-than-life personalities”.

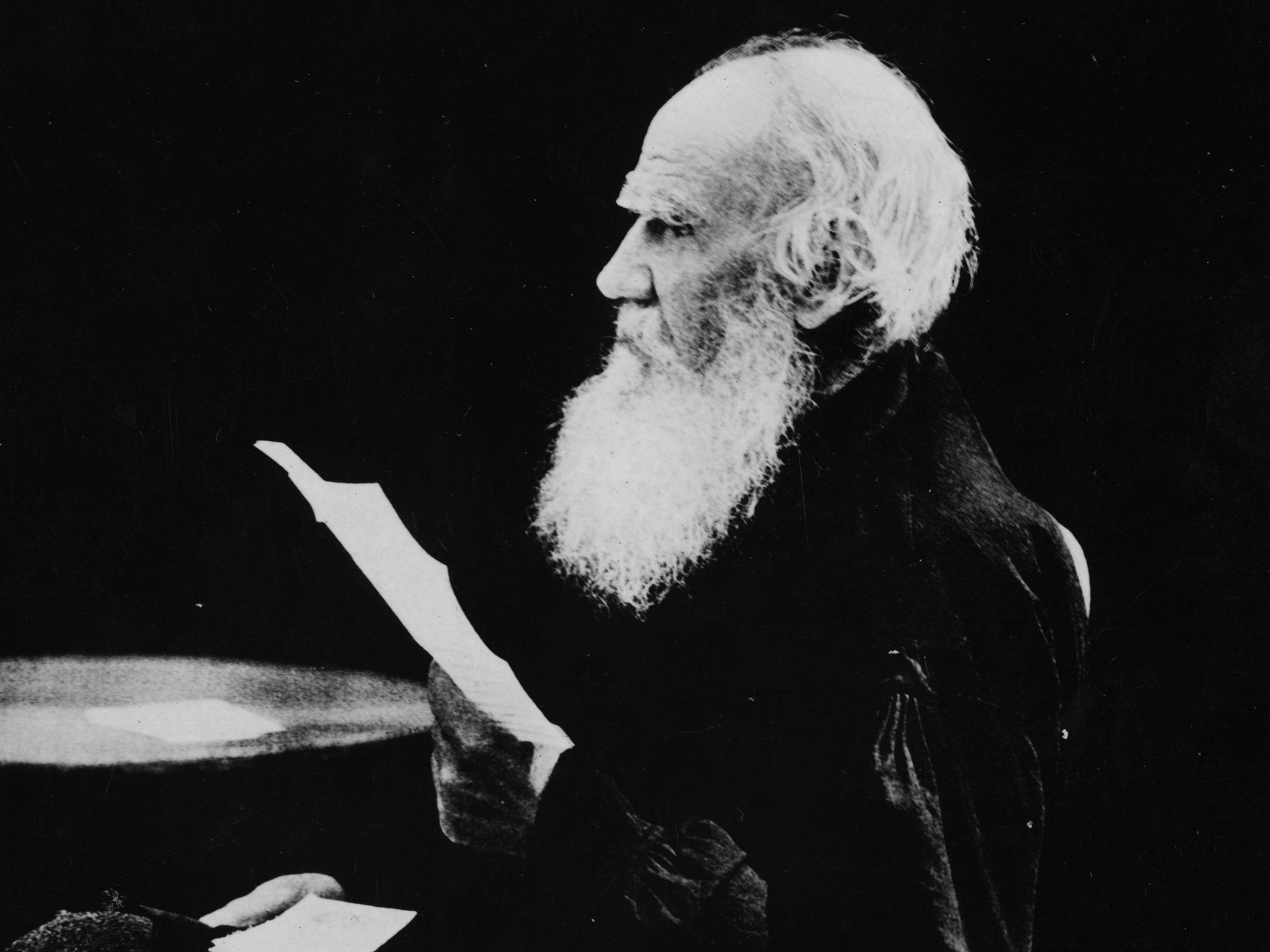

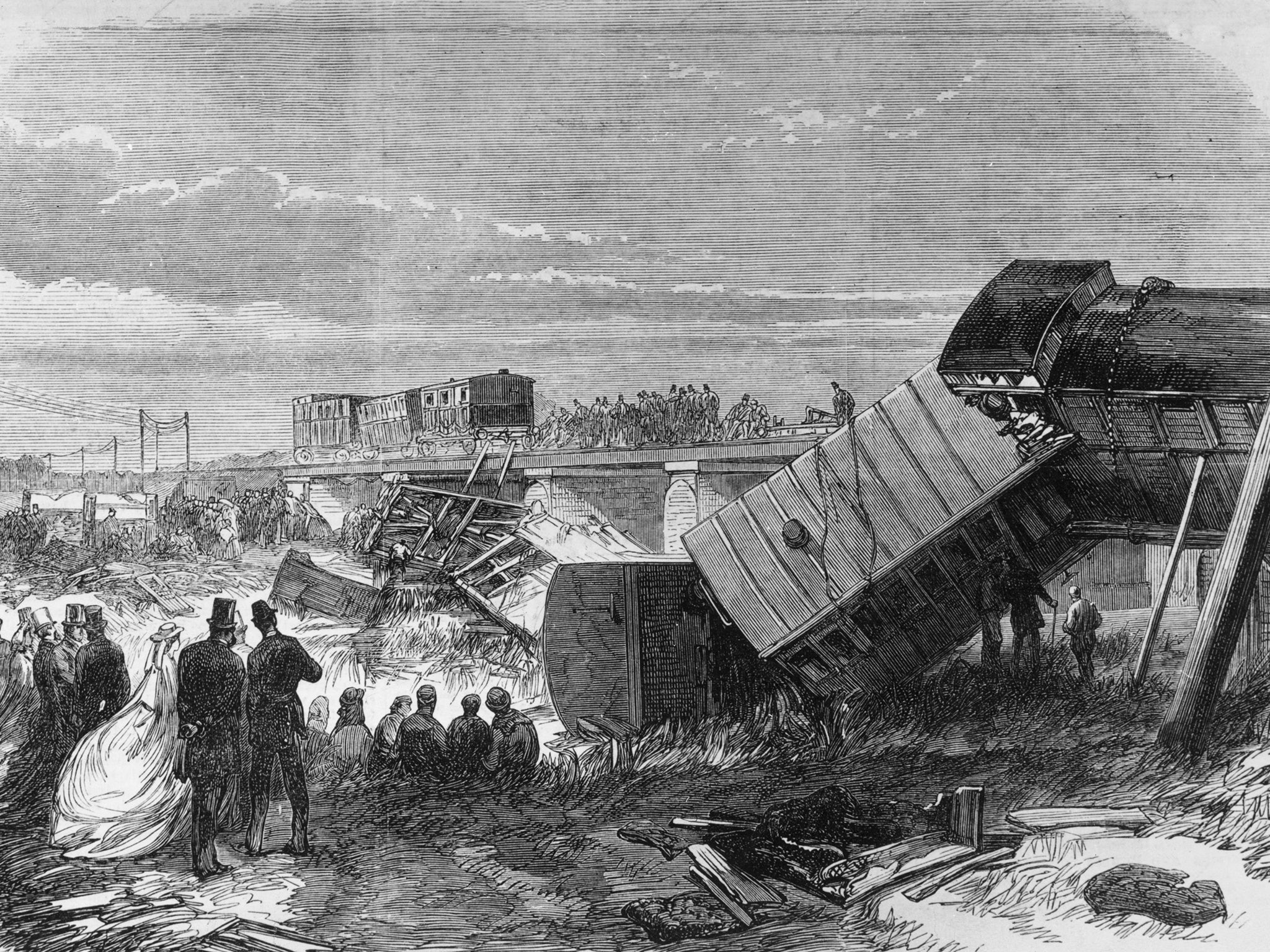

Dickens? I’m not sure if he was “larger-than-life”. He was certainly a celebrity, reading his own novels across the United States, just avoiding scandal with his mistress when, returning from Paris, they were involved in a train disaster near Staplehurst. But when I was at school in the late Fifties, Dickens was regarded as a Victorian “pop” writer, who had spun out his stories for newspapers – or “periodicals” as they were called at the time – producing mawkish characters for the public’s amusement – Oliver Twist or Pip, Sam Weller and Little Nell – and thus scarcely worthy of serious study.

Yet by the time I arrived at Lancaster University, Dickens was a set book. Hard Times was a study of capitalism and Victorian hypocrisy, Bleak House a guidebook to class oppression and innocence betrayed. Oddly, A Tale of Two Cities, with its chilling final executions, was the one novel I could tolerate, probably because it was set in the French Revolution. It also involved political and moral sacrifice, which gave it a modern resonance in the 20th century.

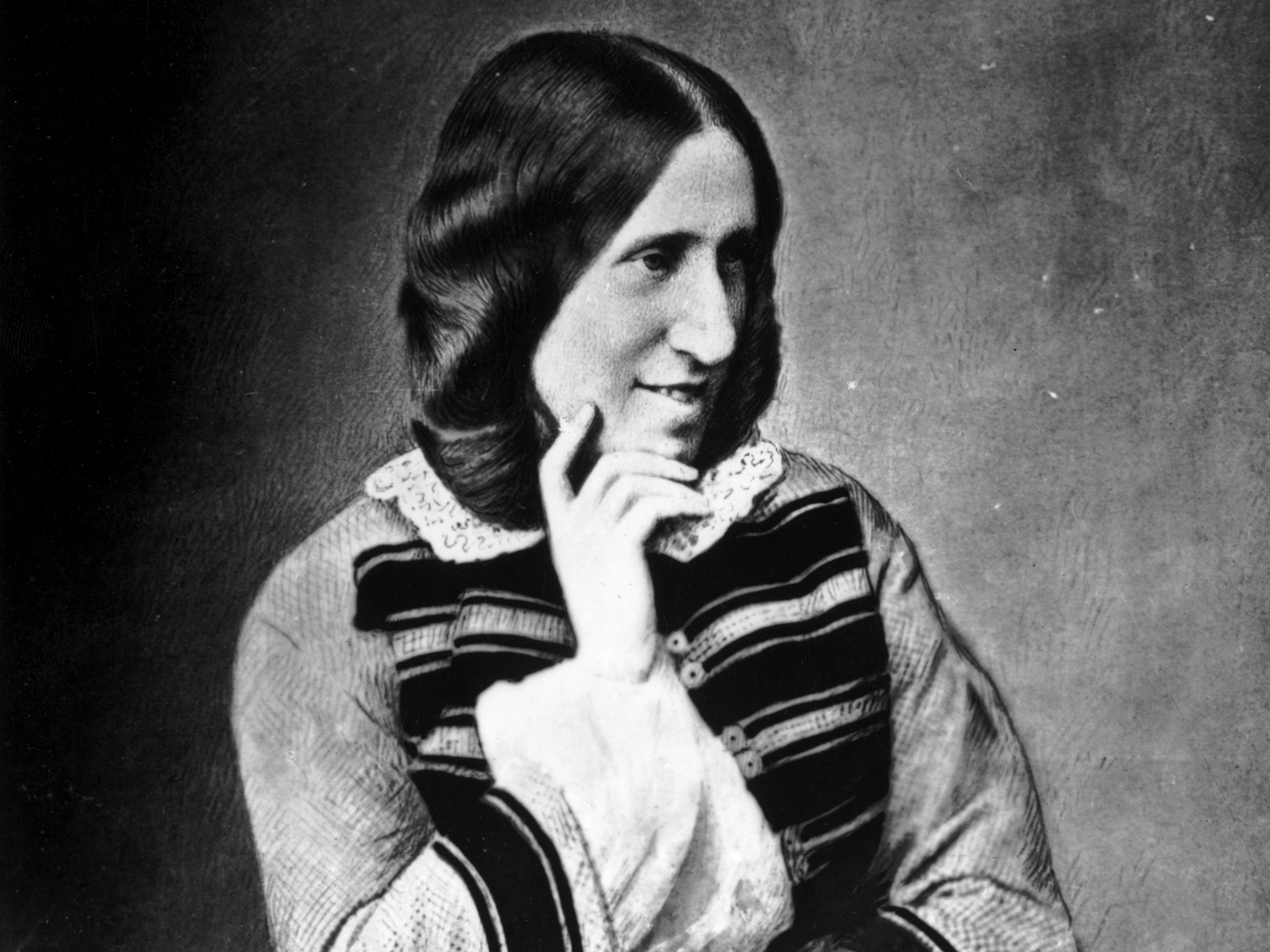

Leavis would infamously announce that “the great English novelists are Jane Austin, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad”, leaving out, as he mischievously declared, the Brontes, Trollope, Wilkie Collins – and Dickens. But the latter’s tomb in Westminster Abbey calls him “England’s most popular author” (which is not the same as ‘England’s greatest’) and even Leavis was to admit in later years that Hard Times was “a masterpiece”. I would put George Eliot on my own list, if only because Dr Tertius Lydgate’s wife Rosamond, as she ostentatiously brings her jewellery downstairs in a melodramatic offer to humiliate her financially distressed husband, is pure Maeve Binchy. It is the most painful scene in Middlemarch: “This is all the jewellery you ever gave me. You can return what you like of it, and of the plate also. You will not, of course, expect me to stay at home tomorrow. I shall go to papa’s.”

The oriental-Zionist themes of Eliot’s Daniel Deronda never interested me (as it did Edward Said). Yet I agree with Leavis on Conrad, not because The Secret Agent – the first “terrorist” novel – was on my Lancaster set book list, but because I once wanted to be a merchant seaman (this was after I gave up the ambition of being a steam locomotive driver), and Conrad’s 1897 description of seafaring reaches heights I had never experienced before as a pilot’s tug out of Bombay leaves the merchant ship Narcissus at dawn:

“Twenty-six pairs of eyes watched her low broad stern crawling languidly over the smooth swell between the two paddle-wheels that turned fast, beating the water with fierce hurry. She resembled an enormous and aquatic black beetle, surprised by the light, overwhelmed by the sunshine trying to escape with ineffectual effort into the distant gloom of the land … On the place where she had stopped a round black patch of soot remained, undulating on the swell – an unclean mark of the creature’s rest.”

You feel those minutes. And she jumps. There are no words – save for the pilot shouting ‘Now!’ – and we never see or hear from Masha again in the novel

Strange, I always think. This could have been written by a Booker prize contender today, though surely not with its original title, The Nigger of the Narcissus. On its publication in the US at the very end of the 19th century, it was changed to The Children of the Sea – not because of the name itself, but because Americans would not wish to read about a black man. Having been a seaman, Conrad could write in what to us is a very contemporary style. His seamen talk roughly and to the point. They give commands and they swear.

So do a lot of characters in Russian novels. Read that great Second World War epic Victims and Heroes (published in Russia as The Living and the Dead) by Konstantin Simonov – he who wrote the unforgettable poem of love and loyalty, “Wait for Me” – and you find that the soldiers breaking out through the German lines in the disastrous summer of 1941 speak in military orders rather than conversation, and are sometimes killed in mid-conversation. Masha, after a last night in Moscow with Sintsov, her husband, departs in a Soviet aircraft to be parachuted behind Nazi lines near Smolensk. The aircraft approaches the drop zone. “And now,” writes Simonov, “aware that she was spending her last minutes inside the plane, she felt nothing but terror.” You feel those minutes. And she jumps. There are no words – save for the pilot shouting “Now!” – and we never see or hear from Masha again in the novel.

Only later, when Sintsov, advancing through the snow through burning villages, comes across the frozen, hanging corpse of a young woman partisan do we think of her again. It is not Masha. But we fear for her to the very end of the book and, because she does not reappear, we go on fearing for her long after we have finished Victims and Heroes. It is a flawless conceit upon the reader. Masha disappears from the text. And thus becomes timeless.

Simonov’s book was the first Second World War epic to be published in Moscow after Stalin’s death, and so the calamity of 1941 and the Soviet army’s unpreparedness for war after its years of Stalinist purges gives to the book a depth hitherto unknown in Russian literature of the period. It was swiftly followed by Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

But before we get carried away with more “great literature”, let’s take a look at that most “popular” of spy writers, Len Deighton. No great literature there, surely. The Ipcress File? Funeral in Berlin? This was the stuff of airport bookstalls. But so was his extraordinary novel Bomber, which broke every remaining taboo about the RAF’s area bombing of Germany in the last war – and which remains for me one of the truly memorable books about the conflict. Deighton’s friend Anthony Burgess praised it as one of the 99 best novels since 1939, not least because of the author’s astounding research.

But it is also a book about betrayal. Of the taking of young British lives high over Germany, of the civilians roasted to death by their bombs, of the pilot who promises to bring back his crew but carries the vile remains of his turret gunner off his wrecked aircraft with the words “you’ll be alright, Jimmy”. Of the dead seven-man Lancaster crew who knew only each other and “who could blame the men who came back for preferring that their friends survived rather than seven strangers”. And of the German officer who receives a letter from his now dead son on the Eastern Front, in which the young man reveals that he has been seducing the equally young woman whom his father – unknown to him – intends to marry. She, too, dies in the RAF raid which, it’s clear at the end, attacked the wrong German city.

The countryside in Bomber is the air, the clouds, of cold fronts and humid summer nights and rain crashing 10 miles through the sky. This is tragedy without flaws. Its action takes place over 24 hours. It feels like a year. Can we not upgrade Bomber to “great”, as my Lancaster English tutor did to Dickens?

And if so, can an author be downgraded from “great” to popular? I suspect that Hardy was too popular (and wealthy) for Leavis, who wrote of his “gaucherie”, to regard him as a “great” novelist (poetry is a different matter). Hardy’s “Wessex” countryside is small, cluttered, full of sleeping birds and ruined houses, as claustrophobic as the countryside of Russian novels is massive and awe-inspiring. So here we go again: Tolstoy, Solzhenitsyn, Pasternak even. Yet maybe the movie of Dr Zhivago downgraded its greatness. On the screen, Omar Sharif and Julie Christie over-romanticised Pasternak’s Yury and Lara, just as Hardy over-romanticised Tess of the d’Urbervilles in his novel.

The horror of the first published lists was that nobody was utterly certain whether this was a list of known dead or known living. So to hear a name read from a list could have meant the best or the worst

It’s always struck me that Hardy had to turn Tess into a murderer – she very finally stabs Alex, her seducer, to death – while Zhivago neatly turns away from such finalities; Lara can’t even shoot straight and, in the movie, only wounds her seducer Komarovsky. In the book, she wounds Komarovsky’s friend. But I have often asked myself what Hardy and Zhivago would have done with their heroines if they had reversed their actions. If Lara had been a better shot and killed Komarovsky, she would surely have been hanged – and thus been eliminated in the early part of the novel. Yuri would have remained true to his marriage. If Tess had merely wounded Alec, she could never have proved her love for her husband Angel. So her hanging is the end of the novel. Far too romantic, if you ask me.

This is not a plea for bad books. Long before Fifty Shades of Grey, we had Penny Dreadfuls. Maeve Binchy was no Jackie Collins, thank God. Maeve’s novels sold only 40 million copies against Collins’s 500 million. But there was a soul in Maeve which you could see clearest not in her fiction, but in her journalism, the craft in which Dickens flowered.

In the 1974 Cyprus war, reporting for The Irish Times, Maeve came across an old man, a Christian Maronite in a Turkish village, whose wife had been murdered. “His poor wife was in heaven now… They had a small shop. Some Greeks in the next village, young and drunken, had come there late one night, ages ago, like three weeks previously, and demanded food. The old man said they were not open… Back they came on Saturday. Shouting and screaming that it was now war, they had worn uniforms; they came into his shop, to this one only, and shot his wife.”

In 1987, her paper sent Maeve to Dover when the Herald of Free Enterprise sank off Zeebrugge with 253 lives lost. She listened to their families seeking news. “The horror of the first published lists was that nobody was utterly certain whether this was a list of known dead or known living. So to hear a name read from a list could have meant the best or the worst.”

This could be Tolstoy. Or Dickens. Or just plain Maeve. She met Samuel Beckett once, in London in 1980, “pop-lit” meets “great-lit”. He asked about Dublin, appalled to hear that the Pearl Bar had been bought by a bank. “‘And I believe the Ballast Office clock has gone,’ he said gloomily. I agreed and I hoped that he might hit on something that was still there in Dublin. ‘How do people know what time it is?’ he asked.” Good question.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks