Padel is the fastest growing sport you may not have heard of

The sport has been booming for some time across parts of Europe and South America but it’s only just gaining ground in the UK. Rory Sullivan decides to try it for himself

Squash started first, tennis followed closely on its heels and then, almost a century of rallying later, along came padel.

Invented by a businessman in Acapulco, Mexico, in the 1960s as a fusion of the two older racket sports, the new game spread rapidly through Spain and Argentina after facilities were constructed by returning enthusiasts. Decades on, it has found fertile ground in other parts of Europe and in the Middle East. And now, padel fervour seems to have belatedly jumped across to these shores, with approximately 200 courts already in use in the UK and with dozens more on the way.

Although data on such things is scarce, padel is likely to be one of the world’s fastest-growing sports. Padel courts, which are enclosed within glass walls and fence panels, are already a common sight in countries such as Portugal, Italy and Sweden, while Dubai has grand plans to install hundreds in the coming months. Money is also fast pouring into the top level of the game: Qatar Sports Investments, which owns Paris Saint-Germain, has invested heavily in the International Padel Federation (FIP), whose professional circuit is at loggerheads with the Estrella Damm-sponsored World Padel Tour. The two are currently bogged down in a legal dispute which will determine the future of this potentially lucrative game.

For now, at least, people in the UK would be forgiven for not knowing much about padel. Like most Brits, I first came across it abroad, spotting a venue in the Dolomites during a cycling trip last summer. Matches take place on a smaller court than in tennis, but the game shares many of the same features, including a net, service boxes and optic yellow balls. The squash element is brought in by its four walls. Unlike both of its forebears, however, padel is nearly always played as a doubles match, making it inherently more social. Some tout it as the new golf, with operators keen to market it to businesses looking to entertain clients.

Tom Murray, a former professional tennis player, is the head of padel at the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA). But he wasn’t always so keen on the nascent sport. Laughing at the memory, he recalls his initial impression of padel when he lived in Spain as a teenager: “In all honesty, I thought it was a bit ridiculous at first. You use what looks like a little beach bat. I didn’t take it seriously at all.”

Over time, his cynicism gave way to enthusiasm, spurring him on to establish the UK’s first indoor padel club at Canary Wharf in 2012. He is now in charge of rolling out the game in Britain. Murray was approached about the role by the LTA in late 2018, when the tennis federation wanted to assume responsibility for padel, following the example set by its peers in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The move came in an attempt to introduce new audiences to racket sports and to revive ailing tennis clubs, says Murray. It has also done wonders for padel, as it became an officially recognised sport in Britain overnight, he adds.

If the LTA achieves its target, there will be 400 padel courts in the UK by the end of next year. For Murray, it is important that the sport grows at a sustainable pace. He cites Sweden as a cautionary tale: without the oversight of a tennis federation, the private sector there built thousands of padel courts within a few years, some of which are now being pulled down. With less space available and with tighter building regulations in the UK than in Sweden, the speed of development will naturally be slower here, Murray thinks. The financial competition will be fierce though. “It’s become a bit of a gold rush. Whoever can find venues in certain cities is going to do well – because they’re first.”

A British padel boom certainly seems inevitable. Especially as the sport has attracted celebrity backing and investment from professional athletes including Andy Murray and Virgil van Dijk, who plays with his Liverpool teammates on a court at their training ground (rivals Manchester City also have one).

Professional footballers aren’t alone in getting swept up by padel. “It’s a bit like pickleball in the US. Suddenly it’s become a bit of a lifestyle, everyone wants to try it. And because of the characteristics of the game, it’s really easy to pick up. Those who have no previous racket skills can feel like they’re doing well and having long rallies,” Murray explains.

As a keen tennis and squash player, I was eager to see what all the fuss was about. So on a cold, blue-skied December morning, I travelled to the National Tennis Centre in Roehampton with my friend Jonny for our padel baptism. Michael Gradon, an ex-Wimbledon board member who runs the padel court operator Game4Padel, and Andrew Castle, a former British No 1 tennis player, were there to give us some pointers.

Our training didn’t last long. We had a few rallies and a brief run-through of the rules – you have to serve underarm, you can’t hit the walls on the full – and then we started a match: Jonny and Gradon versus Castle and I. True to what I’d been told, the points quickly grew longer and more interesting.

Camaraderie came easily, the scoreline was close and Castle provided a running commentary. “I feel like I’m in Frozen,” he says as a beam of sunlight hit his sports whites and glistened on the nearby frost.

In the end, we buckled on my final service game and lost 7-5. Hiding the disappointment of defeat well, Castle, who is one of Game4Padel’s investor ambassadors, told us why he liked the sport so much. “The joy is in the pattern of play,” he says, noting the length and diversity of the points.

After the match, I sat down for a coffee with Gradon to learn more about the rise of padel, which he picked up on the continent. “I fell in love with this game 20 years ago. Along with lots of people who played in Spain and the Algarve, I used to say, ‘surely padel will take off here?’ People always said it was about to. And I almost got cynical because it never did and no one could explain why it hadn’t. And then suddenly it’s gone crazy here.”

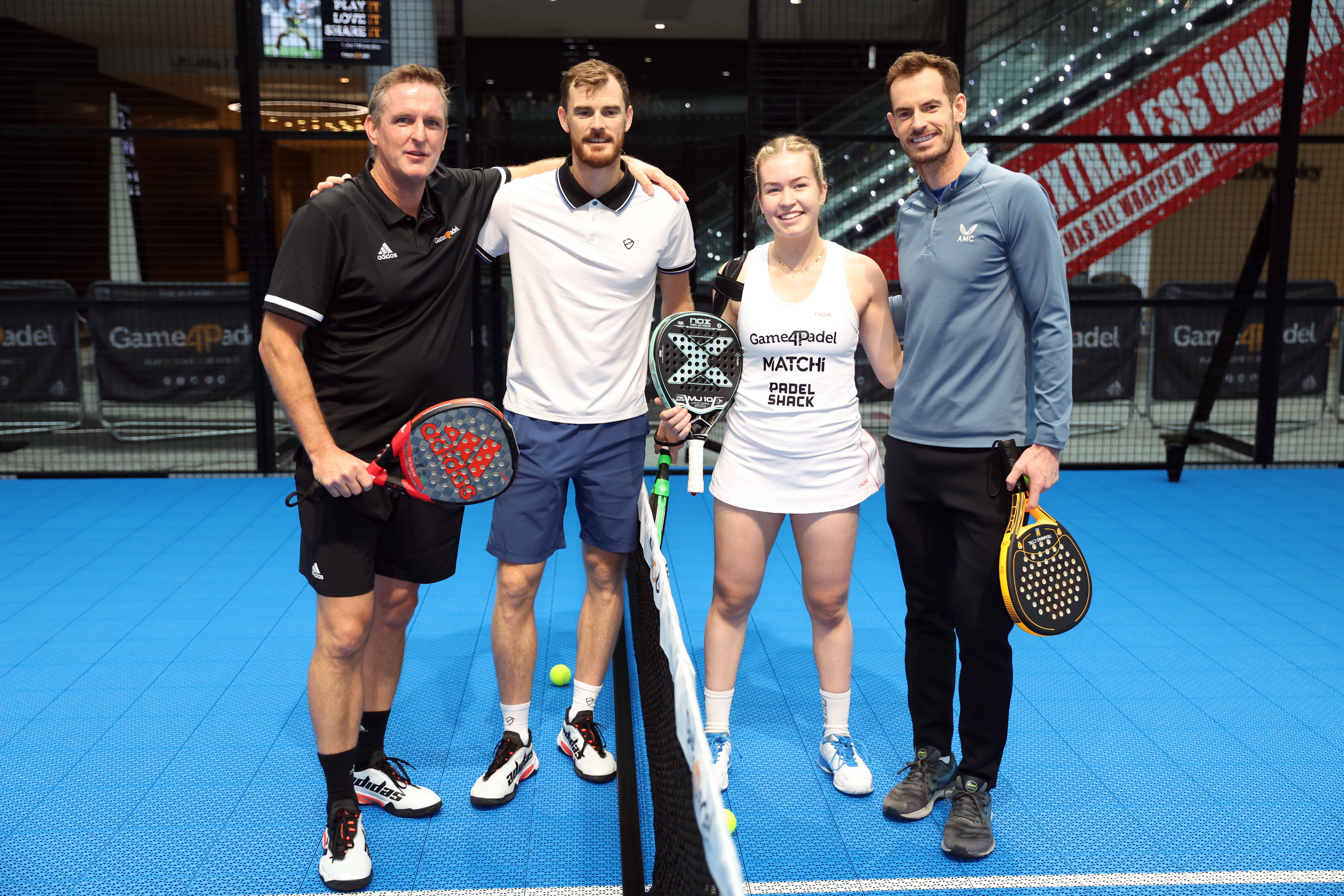

Game4Padel, a company that aims to be the UK market leader and which hopes to expand into Australia, is playing a significant part in publicising the sport. “A few weeks ago we put on by far the biggest padel exhibition the country has ever seen,” Gradon says, referring to a temporary court it opened for three days at the Westfield shopping centre in west London. “We filled it with a mixture of school kids, shoppers who just rocked up, lots of world-class coaches and a bunch of celebrities including Andy and Jamie Murray.”

Even if padel courts do go up quickly in the UK and the pool of players mushrooms, a glance at the world rankings shows the scale of the challenge ahead for the British national team: the top 100 in both the men’s and women’s game are nearly all from Spain and Argentina.

Gradon highlights this disparity by mentioning the Senior World Championships in Las Vegas earlier this year. “In the first round, we played Spain. Every single person we competed against had been on the World Padel Tour. And they’d all been playing their whole life. It’s a bit like me taking up tennis three years ago and now finding myself playing against Federer and Djokovic. The gulf in class is huge.”

Tom Murray, the padel lead at the LTA, believes the game could be an Olympic sport by 2032 but admits this goal is currently being hindered by the overwhelming dominance of Spain and Argentina. “You’d essentially be giving away gold and silver medals to them,” he says. But things are moving in the right direction, according to Murray, who singled out the rapid progress made by Italy and France, who now both have quite a few top 100 players. “They’ve come a long way in a short space of time. Hopefully, we can achieve similar things.”

The UK’s highest-seeded player is 19-year-old Tia Norton, the world number 118. Her tennis coach first got her involved in padel seven years ago. A few months later she flew to Mexico to compete in the Junior World Championships, where she reached the quarter-finals. She remembers the event fondly and credits it with fostering her interest in the game: “I have this photo of me smiling so much. I look incredibly happy. The whole experience in itself was amazing and was a great insight into the world of padel.”

More recently, she decided not to take up a place to study interior architecture at Nottingham Trent University, as she was enjoying the professional padel tour so much. “I’ve basically lived my dream this year,” she tells me. This has involved training in Spain and travelling around the world for competitions in countries such as Denmark, the Netherlands and Mexico.

As well as her ambition to climb the rankings, Norton wants to be an ambassador for the sport in this country. The sooner young players take up the game, the faster Britain will compete at the highest level internationally, she says. The GB women’s team, for example, only narrowly missed out on qualifying for this year’s World Padel Championship, losing to Sweden in the deciding match.

“Countries like Spain and Argentina have had a lot of years in padel. And it’s so new to so many other countries. If you get juniors starting elsewhere now, eventually the nationalities in the rankings will change,” Norton says.

Some people think padel’s dramatic leap in popularity – more Spaniards are said to play padel than tennis – is bad news for other sports. But Norton sees it differently: “Padel is another game added to the racket-sport collection. I don’t think it will take away from the others. If anything, I think it will benefit them. If people enjoy padel, maybe they’ll take up squash or vice versa.”

John Leach, the GB men’s national padel coach who runs the events company Home of Padel, shares this opinion. “It’s providing more participation in racket sports in general,” he says. “I don’t think tennis coaches will look at it warily. I’d imagine they’ll see it as an opportunity. It can be another aspect for them to learn and to teach.”

Squash could be under threat though. Max Lutostanski, who played the sport for the UK, turned to padel seven years ago and now coaches Norton and the rest of the GB women’s national padel team. “I think squash is a dying sport. Everyone’s fighting for padel, which is more social,” he tells me. “Tennis is too big to be threatened.”

Spanish-born Carolina Navarro Björk, who was the world’s best female padel player for nine consecutive years, is optimistic that padel can grow exponentially. “I think that padel is following in the footsteps of tennis, it has had an incredible evolution in the last two years. Hopefully, we can be similar to tennis in every way,” she says, pointing out that the game is now flourishing in “previously unthinkable countries” and that professional competitions are already attracting thousands of spectators.

Like the other experts who spoke to The Independent, Navarro Björk says the legal battle between the FIP and the WTP shows just how much interest there is in padel. “I think that the competition between circuits is good because they improve each other. But I don’t think wars are good.”

Although the future of professional padel remains unclear because of the ongoing lawsuit, the sport’s addictive qualities are not in doubt. A week after our first match, Jonny and I headed out for another game – this time with Leach and Lutostanski at one of the Harbour Club Chelsea’s indoor courts.

I was only partially successful in getting my revenge: when we had to give up the court to the next group, the game was well poised at 6-7, 5-4. Not that the score particularly mattered – more than anything, it was immense fun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments