Oxfam at 75: How the Oxford based charity became a household name

Striving for a world where it doesn’t have to exist is the charity’s very life force

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On this day 75 years ago, in the midst of Second World War, a group of citizens gathered in the University Church of St Mary the Virgin in Oxford. Following occupation, the Greek famine was under way and the group spoke of the urgent need to persuade the British government to allow food relief through the Allied blockade.

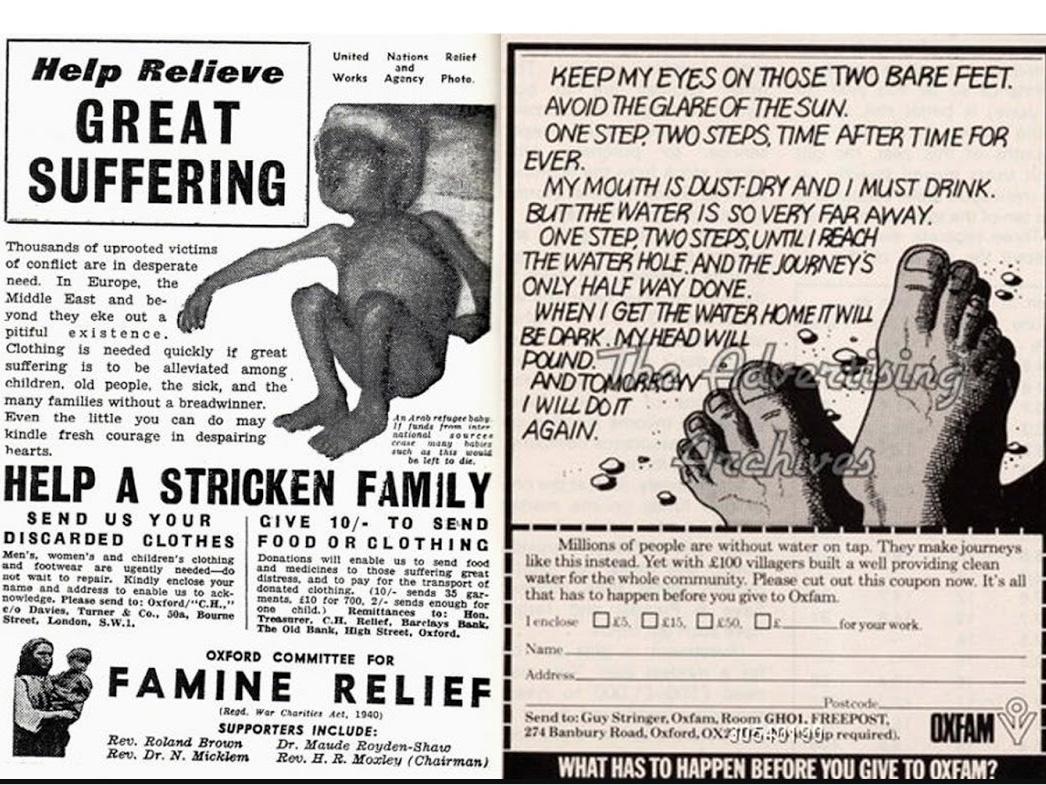

The Oxford Committee for Famine Relief came into being and little did that donnish clique of quakers, canons and intellectuals know that 75 years on, there’d be a music festival called Oxjam, riffing on the acronym coined in the early 1960s (after the Committee’s telex address). Nor could they know that Oxfam would grow so big that it could pressure the President of the United States following his ignoble response to the devastation wrought on Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria; or that the Oxfam Shop would become shorthand for a certain recherché taste.

Oxfam is a household name in the UK: a huge organisation and one of the biggest of the 160,000 UK charities (it currently ranks fourth here in terms of the size of donation). The birthday is bringing on a lot of celebratory fundraising activities, including a sponsored exercise bike race on board a plane from Heathrow to Toronto, as well as a blizzard of fun facts: approximately 10,000 Oxfam staff around the world, a turnover of £415m, 23,000 volunteers in 630-odd shops and 450,000 Brits who give a regular donation to Oxfam each year. “Oxfam’s got a well-established and much-loved place in British society,” says Mark Goldring, the development charity’s chief executive. “This year, we have to celebrate that, and the massive strides we’ve made in the global community in fields like the alleviation of poverty.”

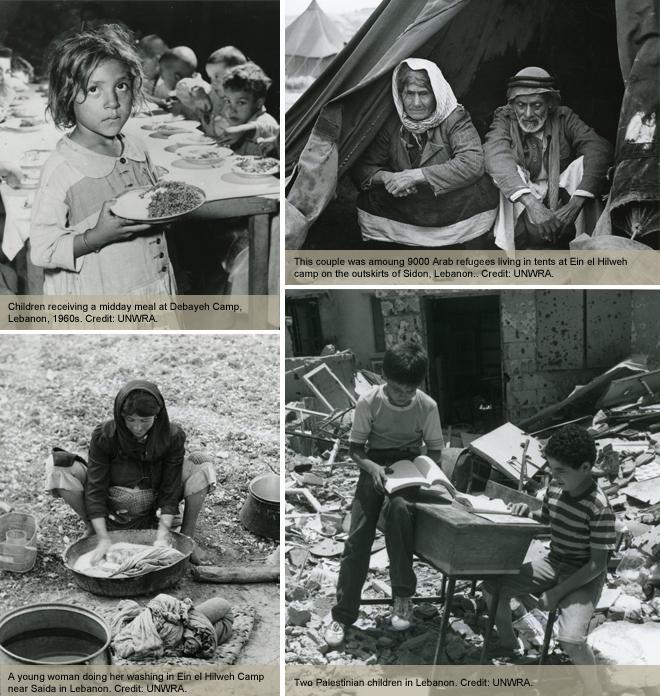

Even by the early 1960s the tweedy members of that first meeting would have been surprised at Oxfam’s growth. The Beatles did a benefit concert in 1963 – an early charity-pop link-up – and Oxfam became increasingly confident and international, shifting its emphasis to the alleviation of poverty in “the [global] South”, as Goldring puts it. “Some things have changed and we don’t refer to the ‘third world’ any longer. But the principles remain.” Indeed, and at present, Oxfam is fundraising for the 500,000 Rohingya refugees leaving Burma – sadly a textbook Oxfam campaign.

By the 1970s Oxfam grew yet further, and began to get increasingly involved in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, leading the efforts against apartheid in South Africa and increasingly seeking to locate the reasons behind poverty, rather than merely seeking to plug gaps as they arose. Oxfam moved towards a role that was more advocacy than aid, raising awareness as well as funds. And at the same time, it built up its network of charity shops which, as Goldring notes, “have become the generic name for shops, in the same way that vacuum cleaners are referred to as Hoovers.”

But within the past five years or so, the charity sector has faced many trials to which Oxfam has not been immune. As well as the crash-and-burn of high-profiles cases such as Kid’s Company and phenomena such as the public ire against “chuggers” (or charity muggers), there is a feeling that the public are increasingly turning on charities.

“Charities were shocked as they thought they had automatic support,” says Joe Saxton, driver of ideas at consultancy nfpSynergy, which last year released a report charting the loss of public trust. The report found public sentiment had swung towards distrust, particularly of large charities which were seen as being overly bureaucratic, looking after their own needs, rather than those of recipients; increasingly aggressive fundraising didn’t help either.

The Oxfam shops

- Oxfam has more than 1,200 shops worldwide with about 630 Oxfam Shops in the UK

- There are about 100 specialist bookshops including books and music

- Oxfam is the largest retailer of second-hand books in Europe, selling around 12 million books a year

- Oxfam’s first paid employee was Joe Mitty, who began working at the Oxfam shop on Broad Street, Oxford in 1949

- A live donkey was among the early donations

- There are about 23,000 Oxfam shop volunteers across the UK

- Last year Oxfam’s shops generated almost £18m

- Since Oxfam unwrapped virtual gifts launched in 2004, it has taken £65m

- Buying a goat to help a family in poverty earn a better living is an Oxfam bestseller

- Oxfam champion Barbara Walmsley has raised more than £400,000 for Oxfam since founding Oxfam’s bridal boutiques in 1986

- Donate your bra – British bras are one of the most-popular items at Oxfam’s social enterprise in Senegal

“The past 10 to 20 years have seen a big drop in trust,” says charity expert Howard Lake, founder of Fundraising UK. “That’s not just in charities but in banks, media, police: you name it, and charities are no longer special in this regard.” The “pass” that the British public once gave charities no longer exists, he says, and no longer were the tried and tested ways of gaining public sentiment so effective. In 2012, a YouGov/Oxfam survey warned that the “Band Aid stereotypes of Africa” were seen as “depressing, manipulative and hopeless’”, leading to a critical dialogue about the diminishing benefits of what had become known as ‘‘poverty porn”.

Then there were the data breaches, the fundraising battles, and the Mail on Sunday, which placed an undercover reporter in a call centre which fundraised for Oxfam, among others. “We got a rude awakening,” says Goldring. “I don’t think we looked ahead enough.” True, Oxfam didn’t sell data itself but it became part of a wider public perception problem in the third sector – charities, voluntary organisations and non-governmental organisations or NGOs.

Oxfam had also picked up a bit of friendly fire in 2005 when the Make Poverty History campaign began, the New Statesman ran a cover story under the headline: “Why Oxfam is failing Africa”. It was criticised by sections of the Left for being too cosy with the UK government and the World Bank while, from the other end of the political spectrum, it has been criticised for being too overtly political (something that goes against rules for charity neutrality); in 2014 the Charity Commission reprimanded Oxfam for a poster attacking the Government’s austerity policies.

As Saxton say: “Charities can’t win. They’re expected to be amateurish and professional at the same time.” They can’t be seen to make money or spend it. But of all the charities, Oxfam has managed to ride out much of the charity backlash by “earning our influence”, as Goldring puts it. “We have had to convince the public and be true to Oxfam. So for example, we are challenging the UK government about arms sales to Saudi Arabia over Yemen.” And it’s countered the notion that it’s an agent of “soft power” by enabling recipients to become self-supporting and encouraging local boards, to which it is accountable.

No one could deny that Oxfam is a highly transparent organisation: even its website shows a pie chart detailing how donations are spent. “It shows that 82p in the pound goes directly to the work, which helps to allay fears,” says Goldring. “I remember 20 years ago, some people had an attitude of ‘I don’t give to big charities’. But we publish it all, so that people can make their minds up, and I believe that biggest charities are often best in this regard.” As for chief executives’ pay – a big bone of contention in the sector – Goldring’s current salary is £125,248..

“It’s an absolute bargain for a company with a £414m a year turnover,” says Joe Saxton.

Yet there’s another factor in the age of marketing: do people still get what does Oxfam stands for? “I think that if you asked ‘What does Oxfam do?’ you might not get a clear answer,” says Saxton. Goldring says that most of us understand that Oxfam is broadly in “food, famine and disasters” but accepts that while the name has a nice ring, it doesn’t have the ‘does what it says on the tin’ factor of say, WaterAid.

Saxton thinks Oxfam sometimes lacks focus. “For example, Save the Children’s ‘No child born to die’ campaign was strong,” he says. “But I’m not sure Oxfam’s ‘Be Humankind’ really worked. I heard people saying ‘What do they mean?’” He’s also struggled with Oxfam’s inequality campaigns. Last year the charity pointed out “62 people own the same as half the world”. “That might be arresting,” Saxton adds, “but the question remains, ‘How do I respond? It’s an un-campaignable campaign.”

Michael Edwards, a writer, academic and ex-Oxfam employee, has written that “without the foreign aid system, Oxfam couldn’t exist”. Oxfam receives government funds for its work, which is about 10-15 per cent of the turnover figure. “But it’s not ‘by rights’,” says Goldring. “It’s a done via grants and contracts, and we’re not beholden to government.”

All of this doesn’t affect the fact that Oxfam believes that peace and arms reduction are vital for development and that poverty and powerlessness are avoidable and can be eliminated by human action and political will – even in what Edwards has called the “multi-polar, post-aid world that’s rapidly emerging” where “Oxfam and the others end up sitting uncomfortably in the middle as the real action takes place around them”.

What would he do if he were still with Oxfam? “I’d work on a 25-year plan to abolish myself,” says Edwards. “One of the founders said that, too.”

That Oxfam is still here is testament to the ongoing need for it to exist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments