Nostalgia is a force we can't escape, and our hankering for the past is only getting stronger

What evokes a sense of nostalgia and deja vu? Andy Martin dives deep to find out the truth

You open the door and you walk in. And the feeling comes over that you have been here before – even though, to the best of your knowledge, you never have. At least, not in this life. And yet, everything has a slightly familiar look. This great castle, or humble fisherman’s cottage on the shore, you belong here, surely! All this is (or was) yours! In a previous life, you must have lived and loved here. Perhaps, indeed, you have already lived many lives and the proof lies in that uncanny sense of deja vu, which gives you a brief glimpse into that time you thought lost.

Or, alternatively, but much less dramatically, you really have been there before – a few bare micro-seconds before, to be exact. The way the brain works, there are at least a couple of tracks with information whizzing around, like the M25, but there’s a fast lane and another one not so fast. The fast one gives you a preliminary dip into the sense data, gathers everything together in a rush, so you get an overall impression (shall I keep going or back off?). The slow track, on the other hand, takes a bit longer to register, sort, sieve, analyse and compare one set of perceptions with others. But what happens if traffic skips across from one lane to another? What if there is a collision? Then you have the potential for deja vu, the sense of having seen this face, this place, once before, because you actually have. It’s twin-track (or split) cognition at work.

So you’ve walked in and your neuro-cognitive system is actually working, thus preventing you bumping into walls or falling down the stairs and suchlike. But at the same time you have this lingering suspicion – wasn’t it better before, back in the good old days, in that previous life of yours (even if it was, in fact, the life you were leading less than a second ago). Our minds have a habit of casting a rosy glow over the relatively raw, virgin form of perception, like snow before anyone has been stomping about on it and messing it up. The idea of the golden age, that once upon a time everything used to be fine, and then it all went to pot, begins right here, after you blink your eyes and take a second look, and disappointment starts to creep in.

Our minds have a habit of casting a rosy glow over the relatively raw, virgin form of perception, like snow before anyone has been stomping about on it and messing it up

If the Big Bang theory is right, then everything really is falling apart, in fact flying apart at high speed. Entropy rules and nothing will ever be quite the way it once was. Similarly, we really are ageing, and drumming up business for doctors, physios, and cosmetic surgeons. And the fact is that England really did win the World Cup in 1966, but not this year. OK, it was close. My sons were singing “Football’s coming home” a lot more loudly than I was. And if I was sceptical it was only partly to do with the likes of France and Belgium. The elusive experience that we tend to refer to as “now” has a habit of losing out both to what was and what will be.

Consider, for example, two recurrent phrases that have captured the collective consciousness in recent years. “Take back control” is one. The other is “Make America great again”. Each has a specific political context, but what they share in common is an implicit tripartite chronology. What both say – and this is the source of their mysterious power, their bewitchment – is that everything used to be just fine, back in the day, and now it’s all gone pear-shaped but we can get it all back on track, and the future will, therefore, resemble the past (thus ignoring the laws of thermodynamics). It’s like we are currently occupying some dark Middle Ages and a new Renaissance (or Restoration) will come along to bring back all those elements of civilisation that we had but were somehow lost along the way. The Danish People’s Party has even taken to saying that they’re going to make hygge great again.

And if there is a religious feeling to all this, that’s not too surprising, because the idea that we started well and then deteriorated is built into religion. How else do you get from God to us? Only if you assume a mighty falling away. We might be “made in the image” of the great creator, but godlike? Really, only on a very good day and with the light just so. One of those Hollywood moments perhaps. And it’s likely that period films and TV have a lot to do with it. Everyone was so much better dressed in Downton Abbey. And wasn’t the Empire wonderful?

Nostalgia has probably always been with us, in some shape or form. But, like everything else, it’s probably getting worse. As a modern phenomenon, it goes back to the 17th century when Swiss mercenaries fighting in the lowlands deserted en masse, dreaming of mountains and the clanging of cowbells and yodelling. So nostalgia was originally the sense of loss of a place (nostos-algos, pain linked to homecoming), but then time and space are effectively interchangeable.

In war, we hark back to peace. But in peace, we hark back to war. Possibly Spitfires and the spirit of Dunkirk. There’s always something, or somewhen, to hanker after. It turns out that those ancient cave paintings, if you study the chronology, are not so much: “Look, the mammoth went that way”; they were – even then – much more likely to be saying: “Look at the lovely antelopes – weren’t they great? Before we hunted them to extinction, that is.” Cave paintings are all like an elegy to what used to be. (And, I can’t help thinking, wasn’t painting so much better back then? It’s all gone to pot since around 40,000 BC.)

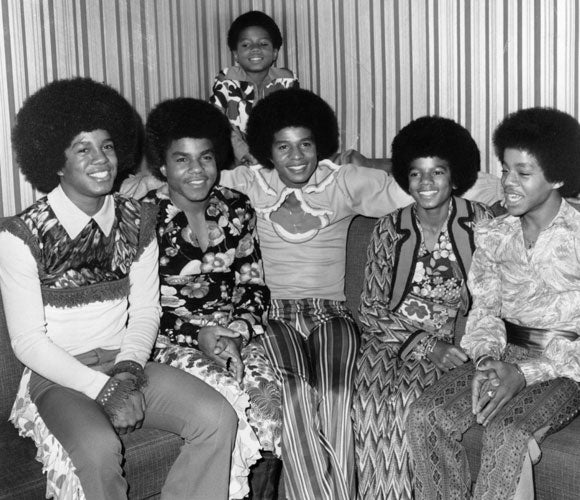

Most love songs are like this. Consider, for instance, Passenger’s “You Let Her Go” and the Jackson Five’s (or Michael Jackson’s) “I Want You Back”. Passenger offers almost a definition of nostalgia: “You see her when you close your eyes”. “I want you back” is the lovesick equivalent of taking power back. The Jackson song featured at the end of Guardians of the Galaxy – like so much science fiction, a blatant exercise in instant nostalgia, hankering after cassettes, which were nothing but trouble. Most of Plato’s philosophy is a variation on this style of poignant love song: it’s all about “recollection” (or anamnesis, literally “unforgetting”). You don’t discover knowledge, you only remember it. You already knew everything there is to know way back, then you forgot it, all you have to do is… get it back again. Which – and this may be relevant to our current circumstances – involves dying first.

“Everything you touch surely dies,” according to Passenger. But then everything you say (or paint etc) does too. Language is brilliant at bringing back stuff that has been lost, giving us at least a virtual image of days gone by, or dead people. It is full of ghosts, designed to talk about things that are not actually there. But, conversely, there is a little bit of the obituary about everything we say. Every novel has a touch of the In Search of Lost Time. But then you abolish the thing you are talking about even as you are summoning it up. Every sentence is a requiem. “Today my mother died,” (the opening line of Camus’ The Outsider), is repeated again and again, with variations, except of course the mother is also thereby resurrected, as is the father, in Oedipus Rex, even while you’re killing him. The whole of religion is right there, in the double act of sacrifice and resurrection.

What if the Garden of Eden really was better? It’s a myth we can’t entirely get away from. Innocence followed by impurity, paradise then the fall. It seems to be hard-wired into us. But what if our brains bear the trace of some real fall from grace?

So it’s hard, perhaps impossible to avoid nostalgia altogether. But I just want to ask one question: what if the Garden of Eden really was better? It’s a myth we can’t entirely get away from. Innocence followed by impurity, paradise then the fall. It seems to be hard-wired into us. But what if our brains bear the trace of some real fall from grace?

A radical shift in human history is memorialised in the Book of Genesis. It’s that point where Yahweh, in indignation at the transgression of Adam and Even, condemns them – which is to say, us – to “tilling the field”: “By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground.” In other words, we are recalling here the invention of agriculture, the shift from nomadic hunter-gatherer to farmer. Cain and Abel – and specifically the killing of poor old Abel – are only possible because they are working “in the field”.

We only have the Bible thanks to the rise of agriculture, cereals and livestock keeping. The Rosetta Stone is all about gods and grain. “We plough the fields and scatter the good seed on the land,” as we used to sing. Only when you have settlement and organised harvesting do you bother to write anything down. Which is why the earliest forms of writing (hieroglyphs and cuneiform) – and the monotheisms associated with them – come out of the fertile sweet spot of Mesopotamia. And the odd thing is they all have a habit of saying something like: wasn’t it great back then, “In the beginning”?

I’ve never taken Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s theory of the “noble savage” too seriously. For starters, it’s just “the good savage” in the original French (le bon sauvage) and we gave it an upgrade. And it is plausible that even Rousseau himself wasn’t entirely convinced and could have been satirising a theory that was already widespread by the 18th century. There’s no reason why any particular period of human history should have been morally superior to any other. But it strikes me as at least possible that they were having more fun back then – hunting rather than farming.

I speak as a vegetarian who has actually tried hunting and stalking, but without killing (I had an elk in my sights in Montana but didn’t pull the trigger). And I think I get it. You’re hunting but you’re also being hunted – by, for example, a bear. That seems fair. There has to be a risk factor, some kind of balance in the equation. A bow and arrow is better than a gun. And at least you’re not sticking pigs and chickens in cages or milking cows. Life as a hunter-gatherer must have been hazardous and precarious, but there was also a freedom of movement, perhaps an intensity, that the settled farmers lost. “Brutish and short”, yes, but “nasty” (as Hobbes suggested)? I can imagine a lot nastier.

Against the Grain, a recent book by James C Scott, reminds us that, in many ways, the rise of agriculture was a disaster. Admittedly we had death before, but at least we didn’t have taxes too. And all those humans living cheek by jowl – this is where a lot of previously unknown infectious diseases kick off. If you want to ease up on the nanny state, try the palaeolithic. Agriculture didn’t just domesticate plants and animals, it domesticated humans too.

Maybe we didn’t have a lot of choice though, because we were so successful at hunting we killed off a lot of animals. We wiped out whole species. We’re good at it. Better at killing than anyone else. And the rise of homo sapiens is synonymous with the decline and extinction of Neanderthals.

Of course, we would try to project the image of Neanderthals as “sub-human” and therefore inferior. Having wiped them out, we would try to justify killing them. We probably just had superior language skills and were therefore, better at organising a Neanderthal obituary. Perhaps we even sang sad songs about them for a while. If we think of them as more like hobbits, it puts them in a whole new light.

For thousands of years, Neanderthals created a successful and satisfying way of life. Perhaps they even achieved a high level of contentment. Possibly they lacked nostalgia. Maybe that’s why they had to go. But not before there was a degree of frenzied interspecies mingling.

Which explains why, if you do a really exhaustive DNA test on yourself, you will find a small percentage of your inner being made up of Neanderthal. Somewhere in our weird multi-track brains we are carrying the memory of an entire humanoid species. And at the same time we know that we are responsible for killing these hobbits, for the primal genocide in human history. Some say it’s a result of infecting them with diseases they couldn’t cope with. But Neanderthal bones discovered in a cave in Spain say otherwise: a group of twelve were killed and butchered by none other than passing homo sapiens, roughly 50,000 years ago. How’s that for a cold case?

Our punishment is to be condemned for all time to remember and suspect that these barbarians were better off back then than we are now. So when you feel that shiver in the soul and you float effortlessly back in time, it’s likely that you are not just remembering past lives, but grieving for past deaths.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments