Northern exposure: From cliche to myth, what does it mean to be from the north?

If the boundaries are blurred, then northernness as a concept is perhaps even harder to pin down… at least from the outside. If you’re northern, you know it, says David Barnett. If you’re not sure, then you probably aren’t

The north is a mercurial territory, and northernness itself a will-o’-the-wispish thing that’s hard to pin down.

We know where the north (of England) ends – that’s Hadrian’s Wall, of course; well, give or take. But arguments as to where it begins rage quietly in the background all the time. Anywhere upwards of the Watford Gap, goes the hoary old joke, if you’re from London.

Research last year conducted by Liverpool University suggested that the north now begins somewhere in Leicestershire, having moved south slightly from Derbyshire. To a northerner from Lancashire or Yorkshire, both those places seem to be more the Midlands… but aren’t Midlanders really just northerners anyway?

We in the north wear northernness like a badge of pride. In 2005, The Wedding Present released a single called “I’m From Further North Than You”. The band is from Leeds, which is squarely in the north. Yet it’s considerably further south than Carlisle, the most northerly city in England.

It would take you the best part of three hours to drive from Carlisle to Sheffield. Sheffield is indisputably in the north, yet skirts those Peak District lands, the Nottinghams and Chesterfields which form the gateway to the Midlands.

Last summer, website The Tab drew up a map showing the north-south divide according to the number of shops of baked goods purveyor Greggs in any particular area, and according to this metric, Sheffield was put in the south.

Ridiculous, of course, as anyone who watched the opening episode of Doctor Who earlier this month will know. The new – and first female – Doctor is played by Jodie Whittaker, who hails from Huddersfield. The entire episode was set in Sheffield, and was as northern as you like – too northern, according to some commentators on Twitter. And heaven knows what the large contingent of American Whovians made of such joyous sight gags as a drunk throwing the salad out of his kebab at a menacing alien.

If the boundaries are blurred, then northernness as a concept is perhaps even harder to pin down… at least from the outside. If you’re northern, you know it. If you’re not sure, then you probably aren’t.

I have lived in the north all my life, first in Lancashire (and the bits re-designated Greater Manchester after local government reform in 1974), and then in Yorkshire. There is a rumour that northerners are warm and friendly, and we are. Or some of us, at least. We’re not exactly all dancing around like Munchkins; there is still a fairly large contingent of people who will rip you off or rough you up or be generally as horrid as criminals are in London.

But, by and large, the general populace does have what feels like a greater empathy for others than we, as northerners, often see on our sojourns down south. Up here in the north we genuinely smile at strangers on the street; often even talk to them. I remember one of my first trips to the capital, to see Wigan play in the Rugby League Challenge Cup final at Wembley. A contingent of Wiganers were standing in Euston station, asking passersby how best to get to Wembley. They were roundly ignored, much to their puzzlement. A little while later I saw a different group handing out song sheets to stony-faced passengers on the Tube, offering to teach them some Wigan chants.

We have space to breathe, in the north. The air’s a lot clearer than it used to be, thanks to various environmental acts and, oh, the fact that most of the heavy industry the country used to rely on us for has long since been closed down. We can get a decent-sized place to live. One of a northerner’s favourite TV shows is the famed comedy programme Location, Location, Location, which features Londoners with more money than sense cooing over properties the size of our toilets (which are all indoors these days, by the way) and which cost four or five times more than our actual houses.

I am being facetious, of course. But it does feel that there is a thing we can call northernness, which might comprise warmth, and friendliness, and humour and grit, but which is much more than the sum of those cliched parts, and much harder to properly define.

Oli Bentley is the creative director of a design studio based in Leeds, called Split. He has taken it upon himself to gather, like wool, various notions of northernness from writers and creatives for a project that was initially part of Leeds’ bid to become the European Capital of Culture in 2023.

A bid which, of course, was thoroughly torpedoed by Brexit, and the news earlier this year that British cities will not be welcome to apply for the accolade after we leave the EU next year.

Undaunted, those driving the Leeds bid decided to build on the legacy of the hard work carried out in the city by holding a year-long celebration of culture in 2023. One of the first projects out of the trap is the book Bentley has curated, called These Northern Types.

Bentley is entrenched in the north. He studied design at Cumbria Institute of the Arts, up there in Carlisle, and while studying at Leeds College of Music after that he set up his Split business from his bedsit. So what is northernness?

“Northernness is a myth,” asserts Bentley. “As a designer, I spend much of my time working with identities – specifically, visual identities for companies, institutions, individuals, bands and arts organisations: brands. I think it is this daily involvement with the perceptions of identities that made me fascinated by this multifaceted, community-owned, slippery thing we call ‘northern identity’. That, and the realisation that, as a lifelong proud northerner, I was beginning to feel unsure about what that actually meant.”

So Bentley went on a journey to rediscover, or perhaps discover for the first time, what northernness really is, if it actually exists, and he went to writers and artists and musicians for their take on it.

That great northern actor Warren Clarke once played the role of a corrupt copper in Red Riding, the TV adaptation of writer David Peace’s The Red Riding Quartet. The books are an astonishing slice of Yorkshire noir, interconnected narratives which weave in and out of the Yorkshire Ripper murders and the subsequent hunt for their perpetrator, Peter Sutcliffe.

Clarke played chief superintendent Bill Molloy, a gruff, no-nonsense copper who you wouldn’t exactly say exuded warmth and friendliness, but instead another aspect of northernness: determination, and the recognition that London is a long way away. Presiding over a group of colleagues in a clandestine meeting, Molloy proposes a toast: “To the north, where we do what we want.”

Molloy and his compatriots meant it for nefarious purposes, but it’s a mantra that endures for less sinister reasons. Here in the north we can’t rely on anyone else; when we do, they rip the rug from under us. We commit with all our hearts and souls and lives to digging coal or tempering steel, and then someone in London closes the pits and the foundries and there’s nothing else for us to do. It is an irony that the north voted, on the whole, for Brexit; a lot of European money was pumped, over the years, into communities ravaged by the death of industrialisation. But the majority Leave vote was born from that suspicion of outside forces exerting too much influence on a region that has been bitten and burned many times.

The Capital of Culture being torpedoed and rising as a legacy project is an example of that determination, as is Bentley’s curating of the book These Northern Types. It is, as you’d expect from someone who trained in design, an artefact as much as a text; it comprises 17 individually-bound books, collected together, and created by some of the most interesting thinkers in the north today.

In his introduction to the book, Bentley writes: “The focus of this project is, at times, less about location, and more about class – an issue that touches nearly every chapter. Or they are about what it is to be ‘other’ to ‘the position of civility... always taken by the seat of power’.

“About living in the other half of the country from the centres of power, finance, media, intellectualism and culture – a situation shared not only with communities from Wales to Dorset to Scotland, but with communities all over the globe.”

These Northern Types offers a taste of the north that is unparalleled since someone in Wigan decided to put a meat and potato pie between a barm cake. It is beautiful to look at yet uncompromising and direct. In the essay “Does It Still Matter Where We Come From?”, Dr Katy Wright addresses whether there is, in fact, any need to align yourself to northernness or anything else.

She writes: “For many – though by no means all – northernness has involved a sense of marginalisation, abandonment and peripherality, which has often been accompanied by experiences of misrecognition, and stereotypes projected from outside. These have involved portraying northerners as, variously, uneducated, opinionated, mean with money, unsophisticated or conservative. Struggling northern towns and cities like Hull, Scunthorpe, Barnsley and Morecambe provide the punchlines to unfunny jokes about ‘crap towns’ and shitholes.”

It is, after all, grim up north. At first it was grim because of the industry that roosted here like dark ravens, the sooty chimneys of Dickens’ Coketown (a thinly disguised Preston), the blackened faces of the miners, the clang-and-heat of the Hephaestan steel forges, the hypnotic rattle of the cotton looms. And then it was grim because the industry was torn down. Grim because of the grit; and we have grit because of the grimness.

Boff Whalley was the guitarist in agit-popsters Chumbawamba; now he is a playwright and the founder of the Commoners Choir. His piece is about northern grit, and how the elements haven’t just formed our dramatic landscape, but do the same to us.

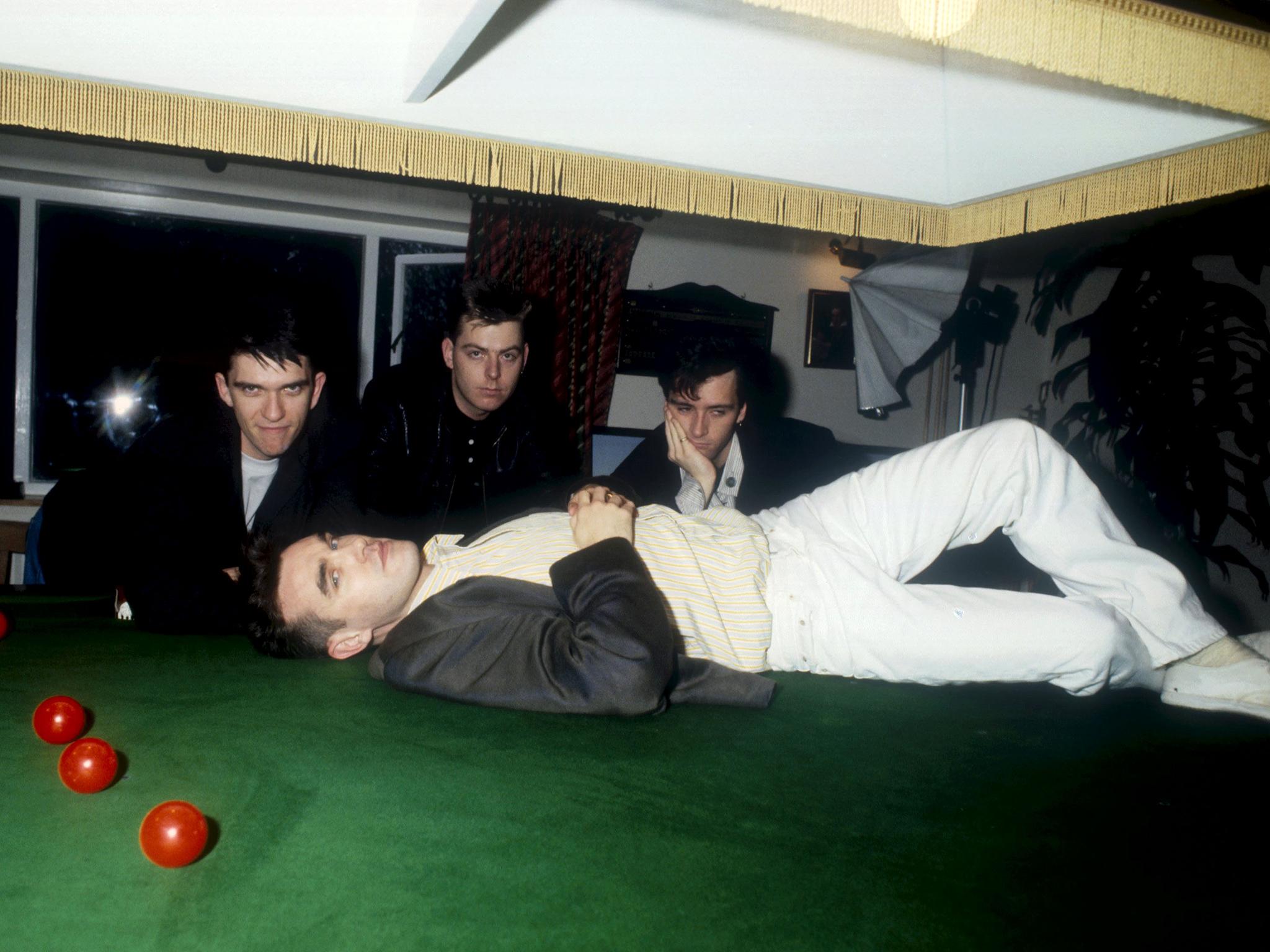

“So much of northern culture – historical, social and political – has sprung from our weather,” he writes. “The Smiths were The Smiths and not the Beach Boys because they were born into a land of dripping raincoats and stone doorways that you huddle into. Ted Hughes thrived on the bleak grey swirl of Yorkshire uplands. Our favourite fiction, from the Brontes to Alan Sillitoe to Ken Loach, is peppered with the drama of rain. Many of Turner’s paintings are suffused with storms, mists and fogs (he climbed the hill above what’s now my home town at the foot of the Yorkshire Dales to make endless studies for his great painterly skies); English films – from Billy Elliot to The Full Monty – are drenched in the melancholy of rain. And what comes of all this dour, dull weather? Resilience. Resolve. Gritting your teeth. Grit.”

Grim… grit… here’s another one for you. Graft. That means hard work. It’s also the name of the typeface Oli Bentley put together for the book and for anyone else who wants to use it. A typeface for the north. Bentley himself questioned the point of the exercise, other than being a nice little artistic project. Then he had another idea: “Let’s use the typeface to work with local community groups across the north. We bring the letters, they bring the words. Then we put these words up in the places they’re from. This led to the idea of printing giant outdoor posters – the sort you can easily and cheaply flypost. To work with local writers to amplify voices – not just listen, but help them be heard.”

Because being heard is something the north struggles with. When we complain that we’re being left behind, we get thrown bones such as the Northern Powerhouse project, an admittedly ambitious plan to boost the economy of the north, put into place by the Conservative-Liberal coalition, much lauded and trumpeted, and then quietly… well, if not abandoned, then at least put on the shelf with the other exciting new initiatives that were going to transform the north, until such time as anyone south of wherever the north’s border is these days cares enough to put money into it. And meanwhile transport – one of the major tenets of the Northern Powerhouse – continues to struggle, with train services especially a bone of particular contention. They don’t call Northern Rail “Northern Fail” for nothing these days.

Boff Whalley mentioned The Smiths and, indeed, music is part of the fabric of the north. Benjamin Myers is an author who this year won the Walter Scott Prize for his novel The Gallows Pole. It brought him £25,000, but his win was largely ignored by the London-centric publishing press. For the book, Myers writes about music, as well, and in doing so explodes a myth about living in the north that is prevalent. His piece is a paean to watching bands, and then forming one, a familiar rite of passage: “You gig round the north, the four of you, with your bad hair and bumfluff ’taches. You play dives and established venues; you play political benefits and school halls and nightclubs and student unions.

“Being in a band forces you to be an adult at 15 as you deal with clueless promoters and jealous death metal bands, American rock stars and patronising regional DJs. You ward off stage-invading Nazi skinheads and cynical producers. You duck flying bottles and you get thrown out of your own shows for being underage.

“You come from that part of the north that rarely gets written about – neither the gritty towns and cities of economic decline nor the dales and vales and uplands, but somewhere in between: the lower-middle-class suburbs. Here is a seemingly endless maze of culs-de-sac and alleyways, tarmac and green spaces, where aspiration exists, and creative seeds are sown, yet which broader culture barely seems to acknowledge, as if the north is either terraced houses or Dales farmlands, Corrie or Emmerdale. It’s not that black and white though; most live in a grey-area Britain.”

Through the works in These Northern Types, only a fraction of which are referenced here, several things seem to emerge. There is something called northernness, but it’s difficult to pin down. We’re just like everybody else, but completely different. We don’t even know where the north begins, nor can we agree on what it really means to be northern.

It’s almost as if the ideas of northernness are laid down by other people, and none of them are what we really feel. But we can’t voice how we truly are inside, because to examine it too closely would make it seem less distinct, less real.

The north is a place made up of individuals, bound by an ethereal quality that is at once a myth and, conversely, as real as grit and graft. Northernness is perhaps something everyone here has, and is, but in subtly and uniquely different ways. The north makes us, and northernness is what we make it. So raise your glasses please, to the north: where we do – and can be – what we want.

‘These Northern Types’ is out now, priced £32, from split.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments