An empire at home: the pitfalls of being brown in the NHS

Our health service is the biggest employer of people of colour in Europe, but, as Neil Singh recounts in his tale of three generations working alongside, and for, the British, that doesn’t mean the age of empire is over

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Where are you from, doctor?” she said, eyeing my name badge. The autumn sun was streaming in through a floor-to-ceiling window nearby, and the ward – not far from the Norfolk coast – was unusually empty, so I was in a good mood to take the question. I’ve been asked this dozens of times, and each time I wonder: are patients really curious about my heritage, or are they Othering me? “Hartlepool,” I replied, archly. I knew what she meant, but I watched her crease her brow before she pushed further. “No! I mean where are you really from... originally?”

A quarter of a million people of colour currently work in the British National Health Service, and all must get asked a version of this question at some point. The real answers, if anybody bothered to listen, would unspool stories of migration from all corners of the earth: stories of struggle, separation, heartache and compromise; of miscegenation and discrimination; of assimilation and humiliation. But that wasn’t the kind of answer she wanted. I had told the truth, but clearly my idea of “fromness” was not satisfactory to her. “India,” I said, with a strange sense of defeat. “Ah,” she seemed content at last. “Well, your English is very good!”

The NHS is portrayed as a national achievement, but it is has always relied on a diverse workforce form across the world. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (or BAME) people make up a quarter of NHS workers, making the NHS the biggest employer of people of colour in Europe. Most of these workers “originate” from former colonies. Does this diversity prove that the age of empire is over? That we live in an era so tolerant that even formerly colonised people can now take up work in the old imperial motherland? Or is there a darker explanation, one which suggests that, in some senses, the age of empire never ended at all, but persists to this day?

I want to share my family’s small part in this larger story, to demonstrate how, even in just one household, empire has inscribed itself onto our lives; defining our personal choices (and the lack of), and casting a long shadow into the post-colonial era. To tell this story, we have to rewind the clock to well before the birth of the NHS, which – by no coincidence – occurred exactly at the moment of the death of the British Empire.

Most Britons are still proud of the British empire, in part because of the hospitals and infrastructure that was built in the 19th century in colonies like India. But few are aware that, in truth, empire was very bad for the health of Indians – in two main ways. First, tens of millions of Indians died of famine caused directly by the British redirecting food away from starving locals and towards British populations. And second, Britain shut down all existing indigenous medical training for Indians in India. In its place, they set up their own medical schools, staffed by and serving white British colonialists, and modelled closely on the British medical system.

At first, Indians were banned from entering medicine, then later allowed to work as assistants. But as the colonial project waned, staffing shortages meant that Indians were gradually able to train and work as doctors, though always having lower status than their white counterparts. Still, medicine became a golden ticket to Indians: one of the only ways to escape crushing poverty and gain some status. This was the world my grandfather, the late Naveen Prasad Singh, grew up in.

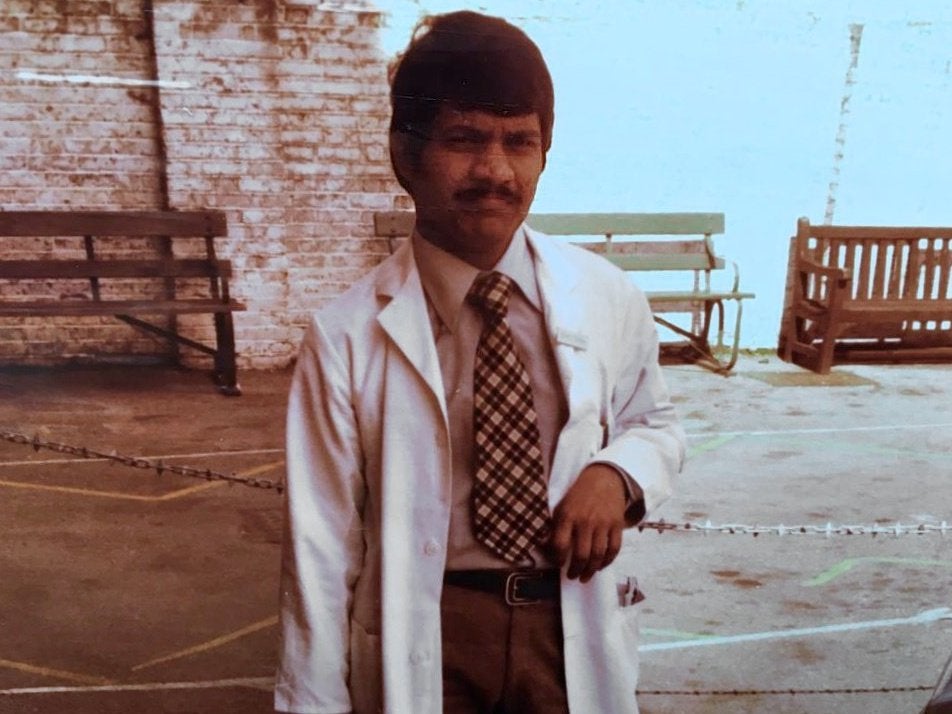

Born in 1922, at the height of the British Empire, into a family of land-owning farmers in the fertile northeastern state of Bihar, my grandfather was the first member of our family to be educated – first, in a Christian missionary school, and then a medical school run by the British. He became the first doctor in my family, and was trained by British medics, whom he admired.

In my grandfather’s lifetime, Indians overcame British resistance to take control of health and science administration in India, and locals like him began to graduate as doctors in large numbers. Indian doctors began forming their own administrative bodies, such as the Bombay and Calcutta Medical Clubs, and the Medical Council of India – which my grandfather was a member of – was founded in 1933. He was working and teaching in the Prince of Wales Medical College Hospital in Patna when independence was declared, and when what had been British colonies became known as the “New Commonwealth”.

The 1948 British Nationality Act granted Commonwealth immigrants the right to settle, vote and access public services in Britain. This triggered the post-war immigration boom

After independence, my grandfather’s generation of Indian doctors filled the top posts, in step with the broader nationalist movement. His trajectory, from the son of farmers to a Professor of Surgery, owed a lot to his Anglophile early education, and would have been unimaginable for an Indian just one generation earlier.

However, the British influence created a cadre of Indian medical graduates who inherited lifestyles and ambitions, not from their parents, but from their medical tutors; whose ideals and working styles fitted life in the west better than it did life in India. Where better to go than the home of the novels you were made to read in school, and the doctors whose textbooks you learnt by rote? Is it any wonder, then, that this pioneering generation’s sons and daughters grew up aspiring to leave India and train in Britain?

Meanwhile, ravaged by two world wars, Britain was left with a huge hole to fill in its workforce and the former colonies became the obvious source of plentiful, cheap labour to rebuild the old imperial metropole. Accordingly, formerly colonised people were actively sourced to work in Britain. The 1948 British Nationality Act granted Commonwealth immigrants the right to settle, vote and access public services in Britain. This triggered the post-war immigration boom, which began symbolically with the arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush into Tilbury docks on 22 June 1948, bringing West Indians to the UK – among them many who would work in the NHS, which was founded two weeks later.

The Commonwealth was portrayed by officials as a utopian achievement. In 1954, Henry Hopkinson, minister of state for colonial affairs, summed up the hope many had of what the Commonwealth could and should be: “We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be, and we can take pride in the fact that he wants and can come to the Mother Country.” Similarly, Clement Atlee, the Labour prime minister who oversaw the formation of the NHS, was a staunch defender of the Commonwealth, as he expounded in his 1960 Chichele Lectures at Oxford University, entitled “Empire into Commonwealth”. The “Commonwealth Sentiment” meant, in principle, an open-door policy to international brotherhood across the former British empire, where all members could travel freely and hold equal rights and access to public goods.

But this utopia was never realised, limited by policies and people that could not truly treat these darker nations as full equals. In reality, while many welcomed the idea of the Commonwealth, many became horrified with the realities of having to live alongside these once-subjugated peoples on their home soil. Both Labour and Conservative governments held secret committee meetings in the 1950s to restrict Commonwealth immigration. This process, of reneging on the promise of full inclusion for Commonwealth migrants, continued and became more open in the coming decades, with ever tighter immigration rules from the 1970s – which is when my parents first landed in the UK.

My parents were invited to this country by Enoch Powell. Not personally, of course, but en masse. Powell spent his formative years in the colonies, and, prior to Indian independence, saw the huge value Britain could extract from putting brown bodies to use for Queen and country: “In discussion of the wealth of India it is usual to forget the principal item, which is four hundred millions of human beings, for the most part belonging to races neither unintelligent nor slothful.”

With this in mind, as Conservative health minister between 1960 and 1963, he actively attracted young doctors from the former colonies to come and help staff the new UK NHS. He spoke of them in warm-hearted terms: “The large numbers of doctors from overseas who come to add to their experience in our hospitals … provide a useful and substantial reinforcement of the staffing of our hospitals and … are an advertisement to the world of British medicine and British hospitals.” Powell’s call was answered by a wave of thousands of doctors from the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the Caribbean, lured by the promise of a better life. By 1976, the General Medical Council had more doctors registered from overseas than from the United Kingdom.

Even in his ethno-nationalist “Rivers of Blood” speech, he earmarked overseas doctors for special dispensation: “The Commonwealth doctors … have enabled our hospital service to be expanded faster than would otherwise have been possible. They are not, and never have been, immigrants.” Current governments share this view that some migrants are worth cherry-picking. Recently, Theresa May relaxed visa rules only for NHS migrants, and there are specific schemes to recruit GPs from overseas to fill vacancies. Accordingly, a third of tier 2 visas for skilled migrants go to NHS employees, at a time when anti-immigration rhetoric is at its peak.

Although the tone has changed over the years, it is fair to say that the British media continues to this day to report on migrant health workers in prejudiced ways, and this has knock-on effects on all people of colour

There is no contradiction here. Welcoming some migrants while rejecting others is not loose hypocrisy, but rather two sides of the same coin. Powell was saying openly what many other Brits felt, but were too afraid to admit: that they were happy to fly the flag of Commonwealth so long as it was on their terms and entirely in their national interest, but that they would rather get rid of immigrants than deal with them as true equals.

So it should be no surprise that migrants arriving to work in the NHS were met with hostility, and portrayed as marauders, such as in Lord Elton’s 1965 book The Unarmed Invasion. The popular press was full of siege narratives, depicting a generous host nation threatened by a wave of Commonwealth immigration that became known as “The Colour Problem”. In February 1969, the London Evening Standard published a cartoon of an African surgeon calmly pushing an enormous “Black and Decker” circular saw towards an operating table, about to slice the patient in two. The patient asks the white support staff, “You’re sure he speaks English? I only came in for my tonsils!” The very next day, the Daily Mail featured a cartoon of an Indian snake-charming healer with the following caption: “Doctor Babu from Bombay, / Very good doctor in every way, / Came to London, National Health, / Plenty patients, / Plenty wealth, / Oh my goodness! Gives wrong unction, / Very soon back in Bombay Junction.”

Occasionally, newspapers tried to assuage their readers’ concerns over migration by portraying it as a necessary evil. After all, as Gary Younge notes: “Whatever sense of racial or national superiority one may harbour, it is likely to be tempered when the black foreigner in the white coat is the one charged with keeping you alive.” Take, for instance, a 1965 article entitled “Life would be harder for all of us without coloured labour”, published at a time when 30 per cent of student nurses and midwives were Commonwealth migrants.

Although the tone has changed over the years, it is fair to say that the British media continues to this day to report on migrant health workers in prejudiced ways, and this has knock-on effects on all people of colour. For instance, after the tragic death of six-year-old Jack Adcock in 2011, the differential media treatment received by the doctors involved – one headscarved, Nigerian trainee Hadiza Bawa-Garba, whose face was pasted above every story like a “Wanted” poster and who was suspended; and Stephen O’Riordan, her white male consultant who was supposed to be responsible that day, but who somehow got very little blame or coverage in the press, and who now enjoys private practice in Ireland – left me and other colleagues of colour feeling unprotected and untrusted as doctors.

[Overseas doctors] are here to provide pairs of hands in the rottenest, worst hospitals in the country because there is nobody else to do it

Until 1976, just two years before my father applied for his first job in the NHS, adverts for medical vacancies could openly state that “only British graduates need apply”. To find out what it was like for my parents to face such a racial hierarchy, we must hear the voices of other doctors of their generation who made similar journeys at the same time.

One such doctor is Aneez Esmail, who grew up in an Indian family in East Africa and moved to the UK in the 1970s. With his gentle face and trim beard, he does not look like a trouble maker, certainly not the kind to be arrested by a fraud squad. But this is exactly what happened in 1993, when Esmail and a colleague performed an undercover experiment to test whether the hiring process in the NHS was racially biased. They had spent seven months sending 46 hoax applications for hospital jobs around the country, sending paired applications and CVs to each post from applicants who were identical, but who differed in one crucial respect: their names. They found that applicants with foreign-sounding names were half as likely to be shortlisted for interview. The results of this study were published in the British Medical Journal, and since then Esmail has continued his courageous research exposing racial discrimination in the NHS, becoming a professor at Manchester University, and declining an OBE for his work in 2002.

Like my parents, Esmail is living testimony to the kind of welcome migrant health workers received. In 2005, he was chosen by the Royal College of General Practitioners to deliver the annual William Pickles lecture, and he chose to give a searing critique of the inimical atmosphere he and thousands of other South Asian doctors faced when arriving in the UK. He said systematic racial biases meant that “Asian doctors ended up working in the Cinderella services of the NHS”, faithfully capturing the fact that migrant doctors were shunted towards less desirable specialties and towns, away from the prestigious teaching hospitals and towards the under-resourced peripheries of the country.

Esmail argued that “[Overseas] doctors became the indentured labourers of the NHS,” since “they occupy the lower-grade positions in the most unpopular specialties with a high propensity for long hours and shift work, from which promotion is restricted and pay and conditions are similarly affected”. Indeed, this was part of the plan. Lord Taylor of Harlow said as much, in a House of Lords debate in 1961: “[Overseas doctors] are here to provide pairs of hands in the rottenest, worst hospitals in the country because there is nobody else to do it.”

My father, having trained at the premier medical school in his state in India, was never offered a job at a teaching hospital, and spent his career moving from one under-resourced hospital to another, from the outskirts of London, to the post-industrial hinterlands of Wales and Scotland, and then finally settling in the northeast of England. It was there that my father’s car was keyed repeatedly while he was at work, and where my mother was called the P-word by a boy on a bike, and where I was raised and educated, before also becoming a doctor in the NHS.

Despite being brown, having been born and raised in Britain, I have had a much easier time working in the NHS than my parents. But I do still feel the ripples of empire in my daily practice. Two autumns ago, I was asked to make a home visit in a care home near our surgery on the south coast of England, to see a 97-year-old patient who was troubled by swollen ankles for a few days. The care home was in a beautiful converted mansion, set in landscaped grounds. After crunching down the gravel drive, I climbed the thick carpet up the wooden staircase to the top floor, and found him in a comfy armchair, facing a bay window which viewed onto green gardens.

Medically speaking, I found nothing concerning that needed treatment. It was a case of providing reassurance and advice, and while doing this I moved on to small talk. Noticing a black-and-white landscape photograph on the bedside shelf, I asked, “What mountain is that?” His eyes lit up immediately. He told me it was Mount Kilimanjaro, and that the picture was taken from his old back yard. “You used to live there?”, I asked with surprise. “Twenty-five of the best years,” he told me, reminiscing about the fine weather and lifestyle he enjoyed there, while posted as a colonial prison officer. I was curious, so went on. “What kind of people did you keep in your prison?” “Blacks,” he said, without blinking. “Black Africans who were seen as... trouble makers.” He paused, weighing his words. “I had to shoot them dead. Dozens of them.” He saw my face change. “I didn’t enjoy it, but those were the times. That was the system we were working under.”

As I left the nursing home, I was filled with a mixture of anger and shame. Anger that I was obliged to serve someone who had committed such horrible crimes, and shame upon reflecting that my obligation to treat him was no less forceful than his obligation to kill Africans. This feeling was tempered by my own professional desire to treat all patients alike, regardless of their background.

But the feeling that I had been wronged by circumstances that meant that I was unable to care for my own sick grandparents in their final years, but required to to attend to the minor ailments of a man who was enjoying his twilight years despite having committed colonial murders, haunts me still. What strange fate, I thought, had brought my family here, from a colony to the motherland, crossing national and cultural borders, to end up working in a place where we were asked to serve people who had conducted colonial violence, like that meted out upon our ancestors!

So, why had my parents come here? Contrary to popular myth, their generation of NHS migrants did not come for the money, nor the passport. We know this from research such as the 1987 report “Overseas Doctors: experience and expectations”, which captures the mindset of the medical diaspora at the time. Medicine is a well-paid profession in all the countries migrants come from, and their relative living standard is often better in their countries of origin. The truth is that migrants often “choose” to leave former colonies – countries sapped for centuries of material and human resources, hamstrung by world trade agreements, and lacking the infrastructure to provide a safe, decent living for public-sector workers – because, in truth, there is no other sensible choice. It takes a very heavy rock and a very hard place to make such workers willing to sacrifice their families, languages, histories and cultures to transplant their lives to an unfamiliar setting where they know they may be treated disrespectfully.

It was not language problems, but rather specific biased processes within the profession, that posed the main barrier to the career development of overseas doctors

In addition, this report shows that most overseas doctors did not come with the intention of staying. Of those surveyed, 82 per cent migrated, not to remain, but to gain further qualifications or experience from the home of the prestigious Royal Colleges and the well-respected NHS, then return with these accolades to their home countries. But despite this aim, two-thirds, including my parents, remained. Why? Because their generation were given jobs which involved a higher proportion of service provision, and consequently they had less access to the teachers, study time and educational resources required to pass the post-graduate training exams which have always acted as a gateway to promotion and security. In effect, they were trapped, semi-voluntarily, in a system that promised much, but was, in practice, nearly impossible for migrants to succeed in.

The result was that two-thirds of these migrating doctors ended up working in specialties that were not their first choice, and half were not satisfied with their experience of the NHS. To return to their homelands without succeeding would have been shameful. So they remained, spending years chasing a mirage and in the meanwhile enduring indignities, insults and injustices that their white counterparts were barely conscious of. I myself have seen their generation of doctors languishing in middle-grade positions that belie their experience and knowledge, forced to obey ward consultants who enjoy far better working conditions, while training up the junior doctors who then go on to overtake them on the career ladder.

But while it was always the system limiting the potential of migrant doctors, the victims were constantly blamed for their failure to progress. Time and again, “communication difficulties” were cited as their downfall. But a study of overseas doctors in the UK in 1980 showed that only 17 per cent had difficulty with English on arrival, and this number shrank after just a short while in this country. The author concluded that it was not language problems, but rather specific biased processes within the profession, that posed the main barrier to the career development of overseas doctors.

I grew up hearing conversations over kitchen tables describing institutional racism, but the data corroborates this too. In 10 years of cases brought to the General Medical Council, BAME doctors were six times more likely to be brought before the Professional Conduct Committee, and 12 times more likely to be charged with indecent behaviour. Furthermore, white doctors are three times more likely to receive excellence awards than doctors of colour. Is it any wonder that I was told I had to work twice as hard to get half as much?

Of course, my parents’ generation also enjoyed many benefits from living in the UK. But moving to a country where – despite being highly trained and highly skilled – you are regarded as a second-class citizen, involves subtle daily humiliations, or microaggressions, that are hard to convey (and rarely spoken of) but palpable to anyone who has grown up in a similar household. Some of these are described, in touching detail, in Sandhya Suri’s remarkable first film, I for India.

Suri condensed over 30 years of home-video footage taken by her father, Yash Pal, into a film that provides a poignant view-from-the-inside of life as an Indian doctor in the NHS. Several scenes chime with my own family. In one, Yash Pal relates, with exasperation, the shame he is made to feel when patients correct his pronunciation of their names, and in the same breath insist on calling him by a bastardised, Anglicised version of his! My own father has spent his entire career as “Bob” because nobody seems able to pronounce his two-syllable, phonetically spelt name: Bimal.

It was also obvious to Yash Pal, as it was for my father, that he was being paid less than his British counterparts at the same grade. Most of the film takes place in the 1980s – the decade of My Beautiful Laundrette, This is England and the Brixton riots: the bad old days. But are things any better for overseas doctors now? This year, the Nuffield Trust confirmed that white consultants earn 4.9 per cent more than their BAME counterparts, including those raised in the UK. Moreover, while a vast number of BAME health workers prop up the system in hands-on positions (they make up 24 per cent of nurses and midwives, and 60 per cent of doctors in posts without progression), they comprise only 4 per cent of management positions. Despite an outcry over these “snowy white peaks” of the NHS, the statistics are actually getting worse in recent years.

The disproportionate placement of overseas doctors in understaffed hospitals puts them, with their steady incomes and good education, cheek-by-jowl alongside neglected working-class British populations in ex-mining regions and seaside estates. This juxtaposition of two groups that have both been long mistreated by Westminster, and yet fail to see their common enemy, means that hospitals have become sites of tension along race and class boundaries.

In 2015, I was working as a senior house officer in an accident and emergency department in a hospital in a south coast town, just a few months before it voted “for” Brexit by a large majority. During one evening shift, I remember looking around at the other doctors and noting their countries of origin. In the entire team, only the most junior doctor was white British. The rest had trained in other countries: Iraq, Sri Lanka, India, Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda and Romania. What, I wondered, is their experience of tolerance in the NHS?

When the patient came to, he told my colleague to leave the cubicle, screaming at a nurse, ‘Get that f****** gorilla away from me!’

I later spoke to the white British wife of one of these doctors, who told me that her black husband came home with stories of racism from patients every week. While stitching up the scalp of one man who had sustained a large gash after falling drunk in the street, the patient said to him, “Get your hands off me, you dirty n*****!” My colleague went on calmly, and did a tidy job of the suturing before sending the patient out without a word. He’s used to it. She then told me of another occasion, when he was in the middle of checking on a patient he was treating for a heart attack. When the patient came to, he told my colleague to leave the cubicle, screaming at a nurse, “Get that f****** gorilla away from me!” These are just two pieces of testimony from just one overseas doctor. Could we bear to hear them all?

It was during my time in this department that the government’s “hostile environment” came into force. Since April 2015, non-EU patients without a visa have been charged in hospitals at 150 per cent of the cost of the care they receive, even if they are NHS staff, contrary to Aneurin Bevan’s vision of a system providing for anyone in the country regardless of migration status. So, a few months after this change, my colleagues and I were receiving emails reminding us of our responsibility to check the visa and residency status of anyone suspected of being chargeable.

We health workers of colour were essentially asked to racially profile migrants, knowing full well that we were on the fortunate side of some concocted line drawn between the highly skilled and those deemed just dead weight. Many of us decided to boycott such plans. But even so, how bizarre it was to think of our team, actively recruited from the Global South to fill employment gaps, being asked to stare into the eyes of brown patients and force them to prove that they deserve the care we were providing, even if they were from the same country of origin!

***

There is no one thing that is to be brown in the NHS. This has been just the story of my household, of three generations of doctors working alongside, and for, the British. But every health worker of colour has their own family story to tell, and to hear them all would challenge our assumptions about what, if anything, makes Britain great. To fully understand our place here, we need to examine our own history and the forces that keep our world unequal. Maybe one day Britain will make amends for the mistreatment of health workers of colour who have kept the NHS afloat – but in the meanwhile, we will continue to quietly serve the patients we care for with all our strength.

Recently, I was called out to assess a couple in their bungalow on a hillside. After wiping my shoes vigorously on my way in, I joined them in the lounge, with a splendid view of the quintessentially English white cliffs through the patio. I quickly scanned the room. Some old poppies were left out on a wicker bookcase in front of a collection of Frederick Forsyth paperbacks. In a cabinet, royal wedding crockery sat near a stack of video cassettes on “The Great War”. I thought of David Widgery, the East End GP and author, who wrote: “Racism is as British as Biggles and Baked Beans ... Racism is about Jubilee mugs and Rule Britannia and how we won the War … it would be pathetic if it hadn’t killed and injured and brutalised so many lives, and if it wasn’t starting all over again.”

The husband looked grateful when he saw me. Taking his slippered feet off a footstool, he folded his copy of the Daily Mail, with a typically xenophobic front page. He said, “Isn’t it awful, all these foreigners coming over here. This country’s going to shit.” I paused, but could not contain myself: “Well, you do know that my family are foreigners here too”. He looked shocked. “Oh no, not you doctor,” he said, looking confused, before letting me examine his hip. “You’re one of us.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments