In Poland, Nato military drills brace against the unspoken threat of Putin

Russian aggression along Europe’s eastern border has Nato ramping up training efforts in anticipation of all manner of warfare – from cyber to chemical. William Cook experiences Poland's biggest Nato operation first hand

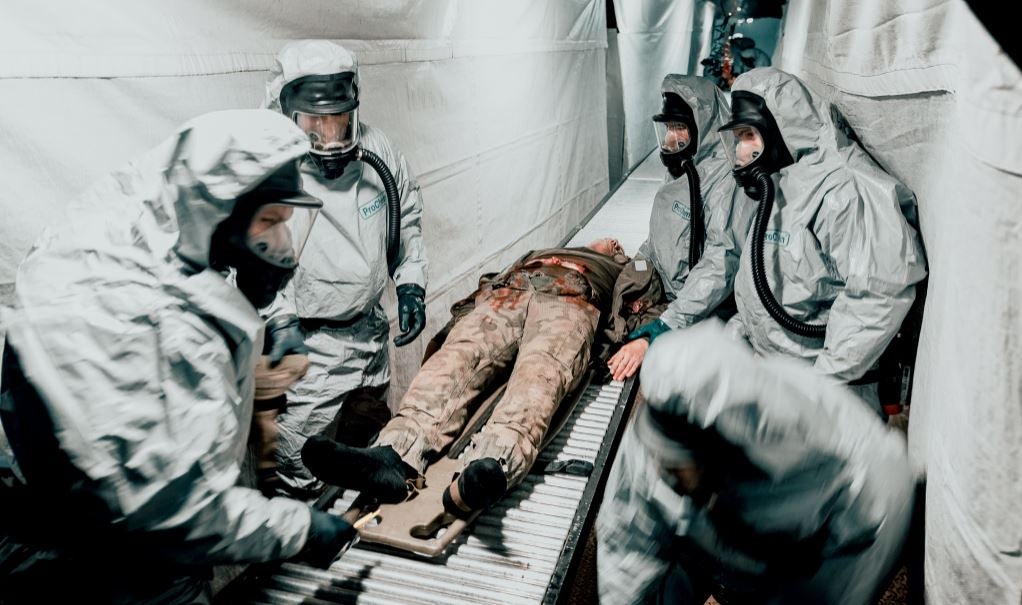

Smoke billows across the battlefield, obscuring the armoured cars ahead of us. A Polish soldier keels over, then another, and then another. Military hardware is no use here – this is a chemical attack. Army ambulances race through the acrid fog to evacuate the casualties. If you’d arrived here unawares, you’d never know this was just a drill – it all feels frighteningly real. Welcome to Drawsko Pomorskie, the biggest military training ground in Europe. And welcome to Anakonda 18, Poland’s biggest Nato exercise.

Anakonda 18 features 17,500 soldiers from 10 Nato members: 12,500 here in Poland, plus 5,000 more in parallel exercises in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. It’s no surprise that these military exercises are happening here. This is the site of Nato’s “Enhanced Forward Presence”: four combat-ready battlegroups, stationed in these four eastern European countries, supporting the defence forces of each of these countries with over 4,000 foreign troops. The multinational makeup of these battlegroups underlines the significance of Article 5 of Nato’s founding treaty, which states that an armed attack against one of its members constitutes an attack against them all.

I’d tagged along on a couple of these Nato exercises before, and though no two are alike, one thing never changes: nobody mentions Vladimir Putin, but his malign influence is everywhere. “Nato exercises are not directed against any country,” reads the disclaimer in my Nato press pack. “They are based on fictitious scenarios with fictitious adversaries.” Yet Putin is omnipresent, the ghost at every feast. A few years ago, he boasted that Russian troops could be in five Nato capitals in two days. He was too coy to name them, but you can be sure they included the capitals of Poland and the Baltic states.

However, the Russian threat isn’t confined to conventional warfare, and Anakonda 18 bears this out. Putin’s invasion of Crimea was overt, but Russian incursions into eastern Ukraine have been more enigmatic – non-uniformed insurgents operating as so-called “freedom fighters”, what commentators in the Baltic states call “little green men”.

Today’s drill is preparation for this sort of threat: an improvised assault by covert operatives using poison gas made from stolen fertilizer. Ukraine isn’t a Nato member, so Russia could occupy Crimea safe in the knowledge that Nato wouldn’t be compelled to retaliate. Here on Nato’s eastern flank, Putin needs to be more canny. For Poland, Article 5 is a powerful insurance policy – but like the cyberwar that Russia has waged so successfully in the Baltic states, there are many ways to destabilise a nation without making an “armed attack”.

Nato refutes Russian accusations

Russian accusation: Nato’s presence in the Baltic States is unpopular and dangerous

Nato response: Nato’s enhanced presence in the region is at the request of the host nations. A Gallup poll conducted in 2016 confirmed that most people in the Baltic states see Nato as a protection, not a threat.

Russian accusation: Nato’s missile defence threatens Russian security

Nato response: Nato’s missile defence system guards against ballistic missiles from outside the Euro-Atlantic area. Bilateral agreements between the United States and host nations prohibit missile sites to be used for any purpose other than defence.

Russian accusation: Nato promised it wouldn’t expand after the Cold War

Nato response: Article 10 of Nato’s founding treaty states that Nato membership is open to any European state “in a position to further the principles of this treaty and the contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area”. Over the past 65 years, 29 countries have chosen to join Nato, freely and in accordance with their domestic democratic processes

Russian accusation: Nato is encircling Russia

Nato response: Russia’s land border is more than 20,000km long. Of that land border, only 1,215km (about 6%) is shared with Nato members. Russia borders 14 countries. Only five of those countries are Nato members

Russian accusation: Nato has tried to isolate Russia

Nato response: In 2014, in response to Russian aggression against Ukraine, Nato suspended practical cooperation with Russia. However, it continues to communicate with Russia. The Nato-Russia Council has met seven times since 2016

As the medics move in, looking like spacemen in their chemical protection suits, Lieutenant Colonel Norbert Holysz explains why the Polish army are training to tackle irregulars in mufti rather than uniformed troops. “The scenario of the overall Anakonda 18 exercise is not during the regular Article 5 operation,” he tells me, as army ambulances rumble past, ferrying casualties to field hospitals. “Now we have to be prepared to fight five minutes before the war.” Five minutes before the war – it’s a potent turn of phrase. Russia currently has soldiers in three countries – Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine – without the consent of their governments. A new cold war has begun, on the battlefield and in cyberspace, and you can be sure the next war, when it comes, will be very different from the one before.

“In my personal opinion,” says Holysz, “the conventional Second World War type of war most probably is gone.” Instead, he foresees a more elusive type of warfare, designed to force political leaders into disadvantageous negotiations. This kind of warfare is already happening in Ukraine. The purpose of these exercises is to make sure Nato troops are able to stop such covert conflicts spreading into nearby countries like Latvia and Estonia, which share land borders with Russia, and Poland, which borders Ukraine.

Russian aggression along Europe’s eastern border has given Nato a much-needed wake-up call. Since Nato’s Warsaw Summit, in 2016, the alliance has raised its game. “We are practicing more often – exercises are bigger,” says Holysz. “The exercises are also better prepared, and they are more real.” Anakonda 18 is one of 106 Nato exercises taking place this year.

Last summer’s Brussels Summit cranked up this process another gear. To repel Russian bots and trolls, Nato has set up a Cyberspace Operations Centre. They’ve beefed up their command structure, recruiting 1,200 new personnel. They’ve also launched a new Readiness Initiative known as the “Four Thirties”: 30 combat vessels, 30 air squadrons and 30 mechanised battalions, all ready to roll within 30 days. America remains the backbone of Nato, but after years of cutbacks European countries (and Canada) are finally stepping up their financial commitments. Never mind what Donald Trump says about Nato members not paying their way. During the last two years these countries have found an extra $41bn (£32bn) for defence.

But the most important innovation has been the growing integration of Nato forces. When nations pool resources there are big savings, allowing countries to streamline and specialise, but above all it’s about pooling expertise. Nato’s Enhanced Forward Presence battlegroup in Lithuania comprises troops from half a dozen Nato countries. The Enhanced Forward Presence battlegroup here in Poland includes troops from Croatia, Romania, the US and the UK. Anakonda 18 includes troops from 10 Nato members, from Germany to Turkey, from the Czech Republic to the Baltic states.

Back at the field hospital, I talk to First Lieutenant Katakrzyna Rzadkowska. She’s enthusiastic about the advantages of Nato’s increasingly multinational approach. “We can share experience, we can learn different languages,” she says. “We are like one team, one army. We work together – it’s not separated anymore.” Lieutenant Rzadkowska is a personification of the modern Nato soldier. She has a bachelor’s degree and a masters. She speaks perfect English. She’s done two tours in Kosovo, and she’s still only 28.

Next morning, bright and early, we see an example of this international cooperation in action. On the outskirts of Chelmno, Czech and Polish troops are transporting armoured cars on rafts across the Vistula river. It’s a precarious manoeuvre: the river is wide and treacherous, and the armoured cars are big and heavy, but together they do a great job.

On the marshy riverbank, I meet up with Lieutenant Rzadkowska again. Born just after the Berlin Wall came down, a toddler when Poland joined the EU and a schoolgirl when Poland joined Nato, her life has mirrored Poland’s transformation, from Soviet satellite to independent sovereign state. “Being part of Nato gives us a lot of possibilities to travel abroad, to work with people from different countries,” she says. “That’s very fruitful and interesting for me, personally, as a soldier.” The life she lives today would have been inconceivable when Poland was behind the Iron Curtain.

We finish up in Gdansk, and at last there’s time for a little R&R. Last time I was here, way back in 1994, Poland still hadn’t joined Nato. It was only a few years since the country had been a member of the Warsaw Pact. Back then, Gdansk was handsome but funereal, and virtually deserted after dark. Now the place is buzzing, with bars and cafes on every corner.

Out in the countryside, Poland is still poor and shabby, but here in the city centre you could be in Bremen or Lübeck. That similarity is no coincidence. Gdansk is Polish now, and always will be, but until 1945 this was a German city – the Danzig of Schopenhauer and Günter Grass. Taken from Germany at the end of the First World War and placed under United Nations jurisdiction, the Free City of Danzig became a source of fierce resentment for Germans between the wars, a resentment ruthlessly exploited by Adolf Hitler. This was where the Second World War started, and when it ended its predominantly German population was expelled. Reduced to rubble by the Red Army, Gdansk was repopulated with Poles, many of whom had been expelled from Polish territory seized by Stalin. Danzig’s tragic history is a reminder of what can happen when diplomacy – and deterrence – fails.

Hidden behind the Iron Curtain, robbed of its original inhabitants, Gdansk looked destined to remain a shadowland, a grim spectre its old self. Yet since 1945 Gdansk has established its own history, drawing on its cosmopolitan heritage as a Hanseatic port. It was here in the Gdansk shipyards that the Soviet tyranny began to crumble, when local lad Lech Walesa dared to start an independent trade union, Solidarity. Former Polish prime minister Donald Tusk (now president of the European Council) was born and raised here, under communism. Like the hero of Grass’s great novel, The Tin Drum, he has Kashubian and German (as well as Polish) roots.

Now the Germans are returning, as business travellers and tourists, and Poles and Germans are united as allies, as well as trading partners. The European Union has done a great deal to bring that reconciliation about, but none of that work would have been possible without Nato. Thirty years ago, with Germany divided and Poland in the Warsaw Pact, who would have thought these old enemies would ever end up on the same side?

Next day was Independence Day and the streets were full of revellers, from veterans in uniform to children in fancy dress. It was a joyous occasion – everyone, young and old, was clad in red and white. I was in Warsaw on Independence Day in 2004, the year Poland joined the European Union, but this year’s celebration was extra special – it was a hundred years since Poland regained its independence. Anyone who says the EU crushes patriotism ought to see this happy spectacle. There were EU flags among these Polish flags. These Poles see the EU as a guarantor of nationhood.

But above all, it’s Nato that’s kept the peace – here in Poland and across eastern Europe, and exercises like Anakonda 18 are a big part of it. Next year it’ll be 20 years since Poland joined Nato, a real cause for celebration, but as I headed for home it was the sober, sombre words of Anakonda 18’s exercise commander, Major General Tomasz Piotrowski, which stayed with me. He explained the purpose of the exercise with the studied neutrality of the career soldier (“hybrid threats emerging along the eastern flank of Nato and, of course, activation of Article 5 to conduct high intensity warfare”) but when I asked him about the background to this exercise, his comments were more stark. He talked about cyber-attacks against Estonia, open warfare in Georgia and instability in eastern Ukraine. He didn’t mention Russia – he didn’t need to. Everyone at this press conference knew the name of the elephant in the room. As Nato’s press office always points out, Nato exercises are based on fictitious scenarios with fictitious adversaries. Here’s hoping these exercises are sufficient preparation if that fiction ever becomes fact.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments