Motherless Sunday: A son’s painful journey to discover his mother’s complicated past

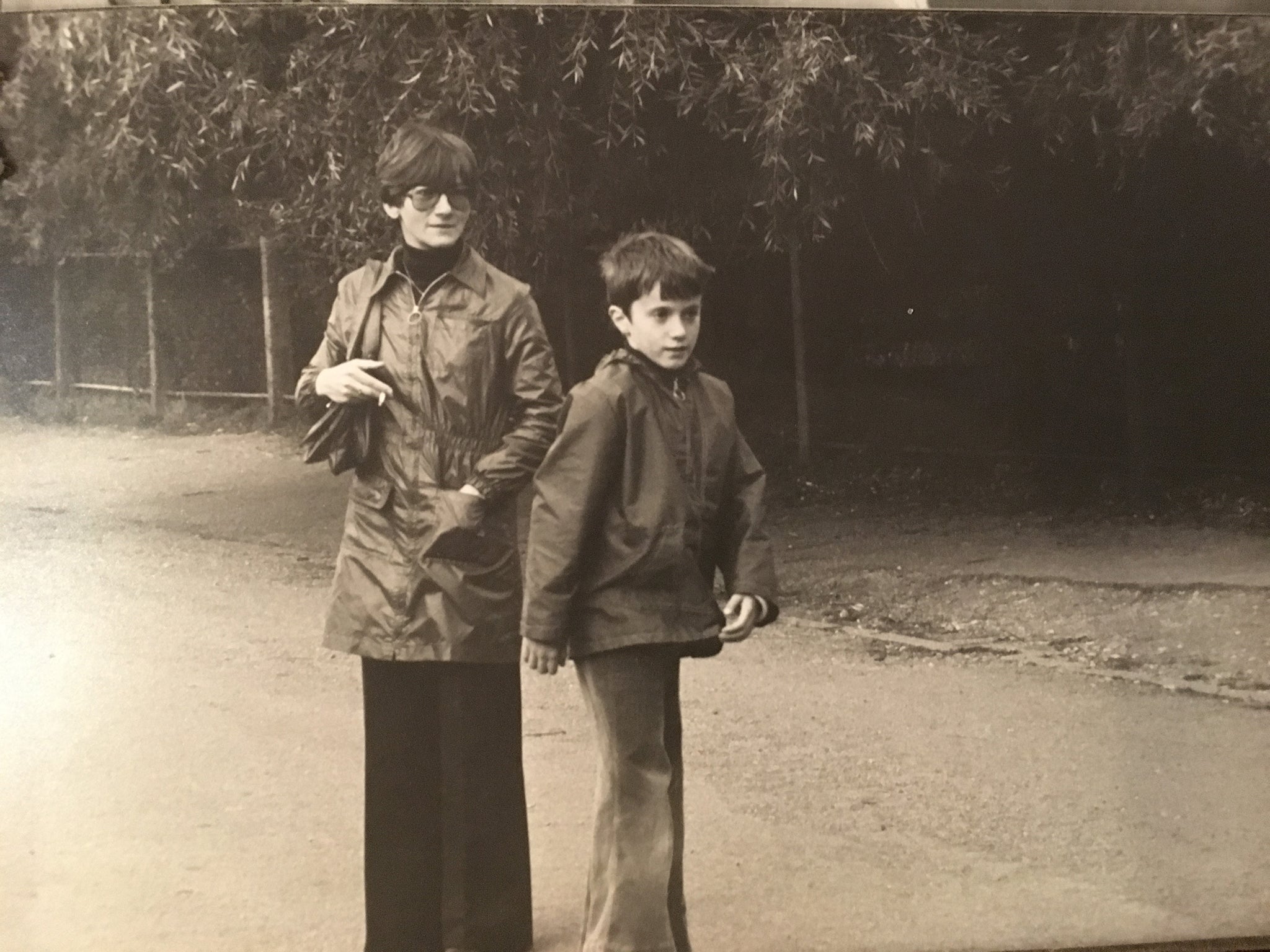

In this moving extract from his newly published book, ‘The Smallest Things’, Nick Duerden explores the difficult and haunting relationship between his mother and beloved grandmother

I always took pains to celebrate my mother on Mother’s Day. She didn’t really buy into it herself, although she did like the flowers. She wouldn’t eat the proffered chocolates – she was on a perpetual diet – but she appreciated the gesture. She was a complicated woman, my mother, and 20 years after her death I tried to find out what was at the root of that complication, and why her relationship with her own mother, my cherished grandmother, had been such a fractious one. Every Mother’s Day since her death, I remember her, and remember, too, just how much I continue to miss her.

A few years ago, I passed the night with friends around a Ouija board. Wine had been drunk beforehand. We spent several bewildering hours suspending disbelief while the planchette swung with gusto around the board’s alphabet, assiduously spelling out messages for us. It seemed that we could request an audience with some of our dearly departed just as efficiently as if we had called them on the phone, and each in turn appeared only too eager to communicate with us, one letter at a time.

We spoke with a dead aunt, a dead grandparent, and their responses were loquacious, melancholic, optimistic and even funny. None of us had any idea what was happening, or how, but it was riveting. After some time, it was my turn. I called up my late mother and, lo, my mother ‘’arrived’’, if that’s the word I’m looking for here. Following my friends’ lead, I asked if there was anything she wanted to tell me, and I braced myself for her answer, tingling with anticipation at what she might wish to convey to me from beyond the grave. ‘N’ was the first letter the planchette alighted on. ‘O’ was the second. “No.”

But I was not put off. There was still so much about my mother, and her relationship with her own mother, that I wanted to learn about, questions for which I now belatedly craved answers. And so I made contact with Loretta, an old friend of my mother’s in Italy, and asked if we could meet. I told her why. She went quiet on the phone before agreeing. “Of course,” she said. “See you soon.”

I have known Loretta for most of my life, and have always liked her. She was cool and chic and slightly aloof, as if designed by Yves Saint Laurent and dressed by Chanel. She was softly spoken and, helpfully for me, spoke perfect English. In the living room of her small central Milan flat a few months later, I took out my dictaphone to record our conversation, but while in one sense it felt just like any other interview for me, the answers she gave me made it unlike any I had ever previously conducted.

It was at some point during the Second World War, she told me, that my grandmother arrived in Italy from her native Yugoslavia. She was with her boyfriend, a nameless Russian. They had been in a relationship for at least a year, and were happy. I wanted more details, but all she could tell me was that, together, they fled to Milan. When she learnt that she was pregnant, my grandmother, an observant Catholic, suggested they get married quickly. He wasn’t interested in marriage, so she abruptly broke off their relationship, and never saw him again.

This single mother then subsequently found sanctuary in a convent, and, at some point later – the details hazy – she met the man who would become my grandfather, an Italian. While he was happy with this ready-made family situation, his own mother (with whom he lived) was less obliging, and would only accept my grandmother if they gave up the child.

“So she did,” Loretta told me. “She sent her to the convent.”

My mother was five. I asked Loretta how long she remained there, but she didn’t know. “Several years, I think. And your mother, she never forgot this, and never forgave her.”

My grandfather’s domineering mother eventually relented, and allowed my mother, now almost 10, under her roof. But, Loretta explained, “she was not happy at home. There was tension.”

My mother and Loretta became friends at school, by which time all my mother wanted to do, in Loretta’s words, was to “go to England, leave her family, and not come back”. And so in 1963, she went to London, where she worked as a nanny and then a secretary, and lived in Finchley, and later on the Earls Court Road. Six months later, Loretta joined her. It was an exciting time to be in the city. London was swinging. The Beatles were happening. These two young friends were now sharing a flat with several other Italian women. They were free, and single, and had disposable incomes.

I asked Loretta what life was like for my mother, at last far from the constraints of her overbearing parents. Did she savour her freedom, enjoy herself? “I don’t know. Your mother was always so… so serious. She was reflective; depressive, I would say. She was always trying to be perfect, and never to do anything wrong. She over-thought a lot, and I don’t think she was an easy person. We were a group of girls, a group of young Italians, but the only one who could really get on with her was me.”

I was inexpressibly sad to hear this, and felt a lump rising in my throat. “She was, I don’t know… too straight, perhaps. She didn’t allow herself to have fun. And she didn’t do the things that maybe one would do when you are free in London at that age. I felt that she always had on her shoulders some kind of responsibility, to do right, to be good.” A shake of the head. “I don’t know.”

By 1968, Loretta back in Italy, my mother met a Yorkshireman who had relocated to the capital to work, initially in the hotel business. Their romance progressed quickly. My mother telephoned home to say that she was getting married. “They were not happy with this,” Loretta told me. “They flew to London to convince her to come back with them. They couldn’t accept that their girl was going to live so far away. But she didn’t care, she just sent them home.”

Following my birth, we moved into a tower block in Peckham, south London, where we would be frequently burgled and where, on occasion, distraught people would take our lift up to the 19th floor, 10 floors above us, and throw themselves off the roof. There were perhaps better places to grow up. My father, by now working in the travel industry, was away a lot, and my grandparents worried for my mother. They didn’t like where we were living, how we were living. They didn’t like him.

“The marriage won’t last,” they taunted. “It will end in tears.” When it eventually did, a decade later, they insisted once again that she return to Milan. And once again, she resisted.

London suited her back in the late 1970s and early 1980s – and her idiosyncrasies. She was likely the only yoga enthusiast in Peckham and probably the only vegetarian, too

“Your mother was very strong but very stubborn, just like your grandmother, in fact,” Loretta said. “Both women always said what they felt. I know that your grandmother felt guilty for putting her in the convent that time, but she had apologised, she wanted to move on, to forget. But your mother, she never could.”

Loretta fell silent now, and I was amazed by the drama of it all, so much of which I’d never known. I had known she’d felt the instinctive pull back to Italy, and also that she resisted it. London suited her, and what were viewed – back in the late 1970s and early 1980s – her idiosyncrasies. She was likely the only yoga enthusiast in Peckham back then, and probably the only vegetarian, too.

She was extolling the virtues of acidophilus and Echinacea to me a good three decades before I came to see their benefits for myself. But she was hampered by depression and unhappiness. There were secretive bouts of anorexia and bulimia. She was lonely and unfulfilled, forever searching for something that would ultimately elude her. She was angry a lot, rarely at me, always at herself and her inability to break her often self-destructive cycles.

When she became ill with pancreatic cancer at the beginning of 1999, the doctors gave her six months. She lasted 11. Her reaction to it was, to me, slightly deranged. Pancreatic cancer is painful. There is no scale of 1 to 10, because it’s more, always more. At first she took painkillers, but increasingly elected not to. Instead, she appeared to accept it, believing that she had developed the illness because of stress brought on by longterm discontent. She felt she had failed at life, and that this was her ultimate punishment. She would endure it because she deserved it – fate, kismet, karma.

I kept telling her that she should go, that if your grandfather didn’t want to go with her, he would be fine at home alone – and even if not, then to hell with him!

I watched as the cancer did its highly efficient work and transformed her from a woman who, late in life, had found some purpose and contentment – she had left her office job to focus entirely on her pursuit in Tai Chi, and the meditative calm it offered – to someone who had been all but worn away by pain, and driven half mad because of it. I pleaded with her relentlessly: take the morphine, toss the St John’s wort away, allow the doctors to help. But every week I watched her deplete. There was cruelty in this.

Throughout her illness, my grandparents chose not to visit. I don’t remember questioning their decision so much as blindly accepting it. They hadn’t come to London for many years anyway, and always hated travelling too far from home. My grandfather had his routines, and my grandmother had for so long played the loyal wife that this role trumped the secondary maternal one.

My grandmother ultimately did visit, bullied into it – and accompanied – by Loretta. “I kept telling her that she should go, that if your grandfather didn’t want to go with her, he would be fine at home alone – and even if not, then to hell with him! Her daughter was ill! She needed to be with her.”

They came for just two days in October, heading straight to the hospice where they found her curled up skeletal on a bed that had, over the previous weeks, become far too big for her. I had been encouraged by the prospect of their arrival, a mother and daughter reunion, but my mother’s response was hers alone, and nothing if not consistent. She didn’t want to talk. There was no mellowing at this late, final stage. I waited outside in the corridor, leaving them to it.

“They fought,” Loretta told me now. “Your grandmother was crying nearly all the night afterwards, but she wouldn’t tell me why, what their fight had been about. She wouldn’t tell me anything.”

It seems that this is not in any way untypical of families with their buried secrets and festering resentments. We’ve all got them, and not all wounds heal. I had always been aware that there had been some lingering poison there, but never the extent of it, never the full reasons why.

My grandmother had behaved the way she had behaved, and for what I can only presume was good reason. It is a shame that my mother couldn’t accept this, and over time learn to sympathise and empathise. She could have chosen to forgive her, to see things from her perspective: a beleaguered single mother in a devoutly Catholic country where codes of conduct were being forcefully reasserted after the years of chaos that come with war. But she didn’t.

My mother died a month after their visit, on 27 November, the occasion of my grandmother’s 81st birthday. They didn’t fly over for the funeral. Every year thereafter, when I called her to wish her a happy birthday, she said my mother’s name to me, voicing it aloud for no other reason than she had to, a maternal compulsion, and then burst once again into copious tears that extinguished any semblance of celebration, and rendered all further conversation irrelevant.

What else was there to say?

The Smallest Things: On the Enduring Power of Family by Nick Duerden is published by Elliott & Thompson.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks