Seventy-one years later, Gandhi’s influence in India diminishes

Seventy-one years after his death, Mahatma Gandhi remains influential in the western world. But in India, he’s seen as weak and politically out of favour, writes Jeffrey Gettleman

The man’s last footsteps, cast in concrete, lead out from an all-white mansion to the spot where he took his final breath.

On a mild winter day, Mohandas K Gandhi, more commonly known by the honorific “Mahatma” (“great soul”) walked slowly across a stately lawn in New Delhi, India’s capital, leaning on the shoulders of two young women, when an assassin greeted him, touched his feet and then shot the frail 78-year-old three times in the chest.

The grounds where Gandhi crumpled to the ground, and the elegant mansion where he spent his final days, have been turned into a memorial to his life, and violent death. To enter, there is no security check or ticket booth. You walk in off the street, unfettered and free, just the way Gandhi would have probably liked it.

The memorial, the Gandhi Smriti, is perhaps the best place in India to contemplate the legacy of one of history’s momentous figures.

Seventy-one years after his assassination, Gandhi’s global influence is still enormous and his reputation as a force for good remains firmly intact.

Like few others in history, he harnessed the moral firepower of nonviolent resistance, helping wrest India from the British Empire. His example of what could be achieved with peaceful protest has inspired countless others, across different cultures and different times, from Martin Luther King Jr to the so-called tank man in Tiananmen Square.

Well into the 21st century, Gandhi’s halo is still bright in most of the world. Barack Obama picked Gandhi as his dream dinner guest.

But in contemporary India, Gandhi is no longer quite so awe-inspiring, or even relevant. As time goes on, he seems to be falling out of sync with the prevailing trends in Indian politics, although politicians still regularly exploit nostalgia for him.

“I am afraid Gandhi has become marginal,” says Pratap B Mehta, a political scientist who is the vice chancellor of Ashoka University and former president of the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi. “In modern India, the two dominant forces hate him.”

Among Hindu nationalists, part of the demographic base that powers India’s governing Bharatiya Janata Party, Gandhi is seen as weak, Mehta says. Hindu supremacists are still angry at him for expressing so much sympathy for the country’s Muslim minority and for letting Pakistan split off from India.

Some Hindu nationalists have even built statues of Gandhi’s killer, Nathuram Godse, who was once a member of a Hindu nationalist group that prime minister Narendra Modi and many of his political allies also have belonged to. Godse is India’s real hero, some nationalists say.

Gandhi is also out of favour with the Dalits, a class of Indians bound at the bottom of India’s Hindu society for centuries, but who now, with an estimated population of more than 200 million, wield significant political clout.

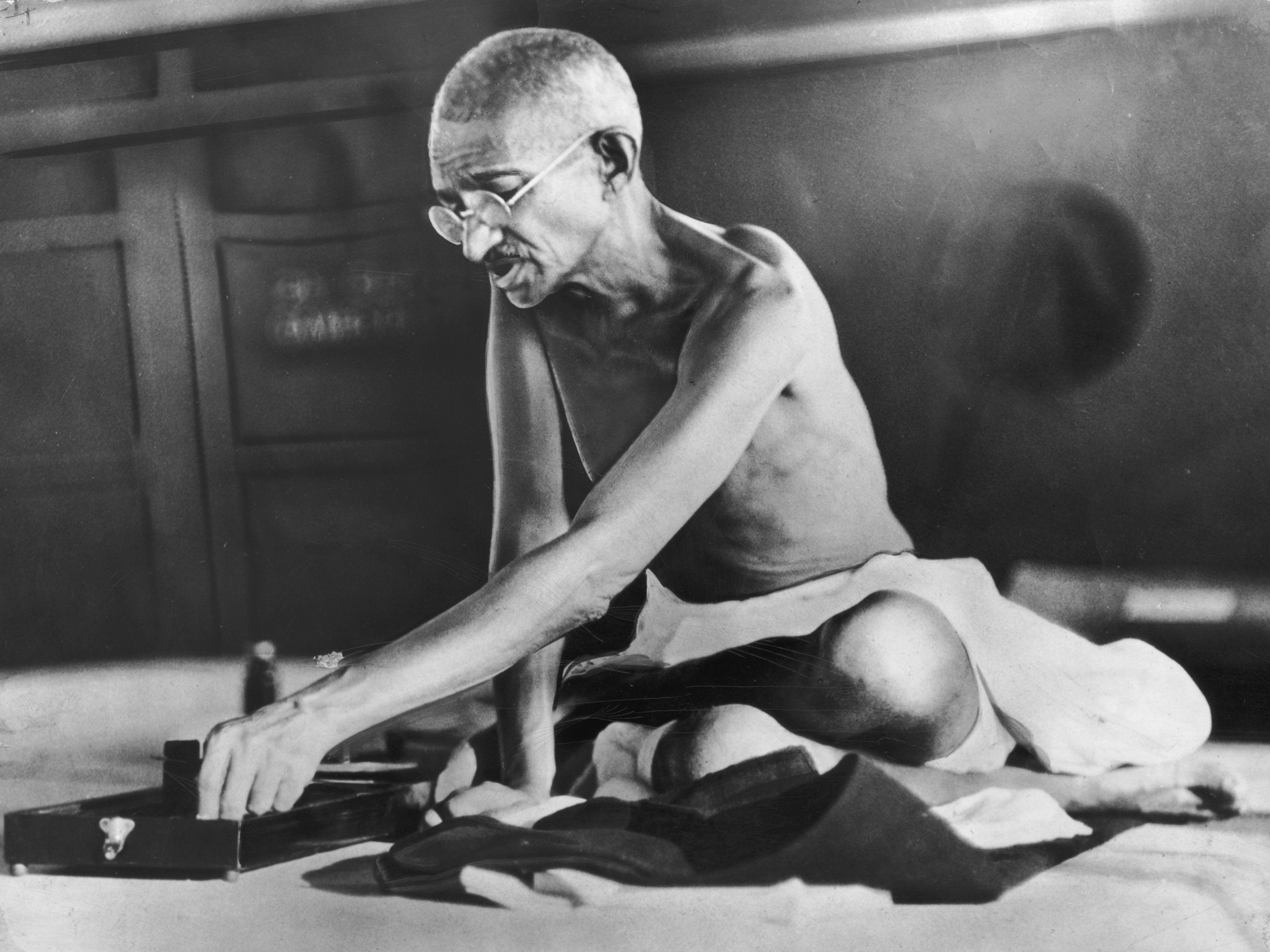

Gandhi was passionate about the poor, including the Dalits, railing against exploitation and living almost like a monk, wearing a simple white loin cloth and famously eating little. After Obama picked Gandhi as his ideal dinner companion, he joked: “It would probably be a really small meal.”

And in an exhibit at the Gandhi Smriti memorial (“smriti” is a Hindi word that means something like “in memory of”), you can peer into his ground floor room and see what are labeled his “worldly remains”: his glasses, a spoon, a pocket watch and a pumice stone to scrub his body.

With such a commitment to the poor, it might seem curious that Gandhi was so comfortable here at a lavish private home built in 1928 for GD Birla, one of India’s early industrialists, who made a fortune from jute – and from others’ sweat. But Gandhi was close to some of the richest capitalists in India – and this mansion, with lush grounds trimmed by tall, bushy mango trees full of chirping birds, is where he often stayed when he visited New Delhi.

His attachment to India’s elite is one reason Dalits and those on the political left can be harsh in their assessment of Gandhi, whom they fault for not doing enough to dismantle India’s often brutal caste system. While he did stand up for the lowest castes, critics argue that Gandhi didn’t question the system itself hard enough.

“They think he was not radical enough and patronising in his call for Dalit emancipation,” Mehta says.

Nearly three quarters of a century after Gandhi helped India win independence, lower caste people are still openly, and shockingly, discriminated against. Just recently, a lower caste man was scalped simply for asking for his rightful wages.

Despite the criticisms, Indian politicians of all kinds do often try to out-Gandhi each other when it suits their purposes, especially the party with which Gandhi remains most associated today.

Gandhi was an early member of the country’s leading opposition party, the Indian National Congress, and helped transform the party from an elite debating club to a national force. Congress politicians often put Gandhi’s picture on their banners, especially when they hold Gandhi-like hunger strikes.

Modi’s government also sometimes tries to channel Gandhi, despite his disfavour with Hindu nationalists. You can’t pass through an Indian village these days without seeing the image of a pair of black wire spectacles stencilled on a wall – Gandhi’s iconic glasses – as a symbol for one of Modi’s biggest social programmes, the Swachh Bharat (”clean India”) campaign. By the government’s count, the programme has delivered nearly 100 million new toilets.

Gandhi’s birthday on 2 October (this year is the 150th anniversary of his birth) remains one of India’s national holidays; and he is a common sight in the capital’s annual Republic Day parade on 26 January, as many floats carried giant models of him.

This political dance with Gandhi – sometimes embracing his legacy, sometimes pushing him away – doesn’t surprise one of his most acclaimed biographers, Ramachandra Guha.

“Gandhi is like Churchill, Napoleon, Mao, Lincoln – any great figure,” Guha says. “His brand goes up and down. His legacy will be debated endlessly.”

Some of the scrutiny in recent years has questioned Gandhi’s sex life; scholars say he lay in bed naked with young women to test his chastity.

The newest debate is whether Gandhi was racist. In December, a Gandhi statue was removed from a university in Ghana after students and professors complained that when he worked in South Africa in the late 19th and early 20th century, Gandhi showed a disdain for black people. Gandhi scholars don’t disagree, though they argue Gandhi later reformed his views.

Asked which of India’s array of political parties have the best claim to being Gandhi’s ideological heirs, Guha leaves no doubt about what he thinks.

“None of the political parties have any credible claim to Gandhi’s moral legacy,” he says, checking off the reasons – spectacular corruption, dynastic politics and religious division.

The only true guardians of Gandhi’s legacy fall outside government, Guha says, like environmental groups, committees that try to protect traditional village life and groups promoting religious harmony.

The guides at the memorial wear rough homespun vests, a distinctive Gandhian touch – he promoted homespun cloth, known as khadi, as an alternative to British imports.

When entering the grounds of the memorial from the hectic streets that surround it, the immediate sensation is one of calm, an island of quiet in an urban area of over 20 million people.

The memorial site is at once stimulating and soothing, haunting yet peaceful. It is as if the aura of the man himself hovers above it.

Part of the reason for the quiet, of course, is that the memorial simply doesn’t attract that many visitors as Gandhi’s importance and pertinence to ordinary Indians fades. But still, some come.

“It’s not like he comes up in daily conversation,” says Manoj Chudasama, a vendor of industrial scales who was visiting the memorial during a visit to Delhi. “But we think of him.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks