We all know about Michael Jackson and Kevin Spacey, but what about Gauguin and Arthur Koestler?

When an artist is shown to have transgressed, his art too is forever spurned. Or is it? It seems to David Lister that there are bewildering inconsistencies over whom we choose to damn and whom we choose to indulge

How did you spend your evening? Few people would dare respond that they were at home listening to a Michael Jackson album, or watching a Kevin Spacey movie. The disgrace of an artist is swiftly followed these days not just by their removal from the public sphere, but also from private discourse. And crucially, any affection for work once held in the highest esteem, is outlawed.

The documentary Leaving Neverland, in which two men recounted in graphic detail their alleged abuse as children by Jackson, was followed immediately by streaming services and, reportedly, Radio 2 banning his music. Even his glove has been removed from a children’s museum in the United States.

Commentators were united as one in saying that such was their disgust with the once revered King of Pop that they could no longer listen to his music (though in the muddled confusion that surrounds these issues, the hit show Thriller, built around his music, continues to draw the crowds in London’s West End)

Spacey, an Oscar-winner and for more than a decade the artistic director of London’s Old Vic theatre, has not yet been tried in a court of law, but accusations of improper conduct against young men seemed damning enough for him to be removed by director Ridley Scott from a movie and replaced by another actor, left out of the last series of TV’s House of Cards, and all but written out of history at the Old Vic.

When the artist is shown to have transgressed, his art too is forever spurned. Or is it? It seems to me there are bewildering inconsistencies in whom we choose to damn and whom we choose to indulge.

The Master of Suspense, the all but immortal film director Alfred Hitchcock, has in recent years been shown to be far from a perfect human being. Indeed, one of his biggest stars, Tippi Hedren, the leading lady in The Birds, who is still alive, has gone on record accusing Hitchcock of serial sexual harassment, mixed with threats to the victim’s career if she did not comply. Yet the Master remains The Master, and there is no sign that the British Film Institute will cease to show Hitchcock seasons.

Michael Jackson had an infatuation with prepubescent adolescent boys and, disturbingly, had them stay at his home. The late Benjamin Britten, the greatest British composer of opera, had an unhealthy infatuation with pre-pubescent adolescent boys and, disturbingly, had them stay at his home. Were he alive now, I suspect that Britten would come under an unforgiving media spotlight. But, as things stand, there is no sign of the Royal Opera House excluding him from their repertoire.

Michael Jackson may well have been a paedophile. Paul Gauguin certainly was. The artist, famous for his paintings of young girls in Tahiti, had relationships in Tahiti with those girls when he was not only middle-aged but had syphilis. Tamar Garb, professor of history of art at University College, London, has commented in The Sunday Times: “Scholars have fought about Gauguin for the past 25 years. He’s a paedophile racist, running around with these 13-year-old girls, who become his so-called wives. Many scholars think it completely compromises you when you look at those doe-eyed, brown bodies and how they were representative of a culture of racism and colonialism.”

At the time of writing, the National Gallery has not considered removing his works from display.

And take the curious case of The Rolling Stones. Bill Wyman, their bass guitarist for over two decades, had in the early eighties, when he was 47 and still a member of the band, a relationship with 13-year-old Mandy Smith, whom he later married. One might have thought that this ‘’relationship’’ between a 47-year-old rock star and a 13-year-old-girl might be enough to see a demand for some sort of sanction against his band. But neither then, nor now, has there been any call by Radio 2 or anyone else to ban their music.

It is not just inconsistency which is disturbing; it is the Stalinist nature of literally writing people out of the script

Such are the inconsistencies and anomalies when one rushes to ban an artist’s work. It is a very vexed area, as I found myself when I became involved in a particularly notorious and deeply distressing case.

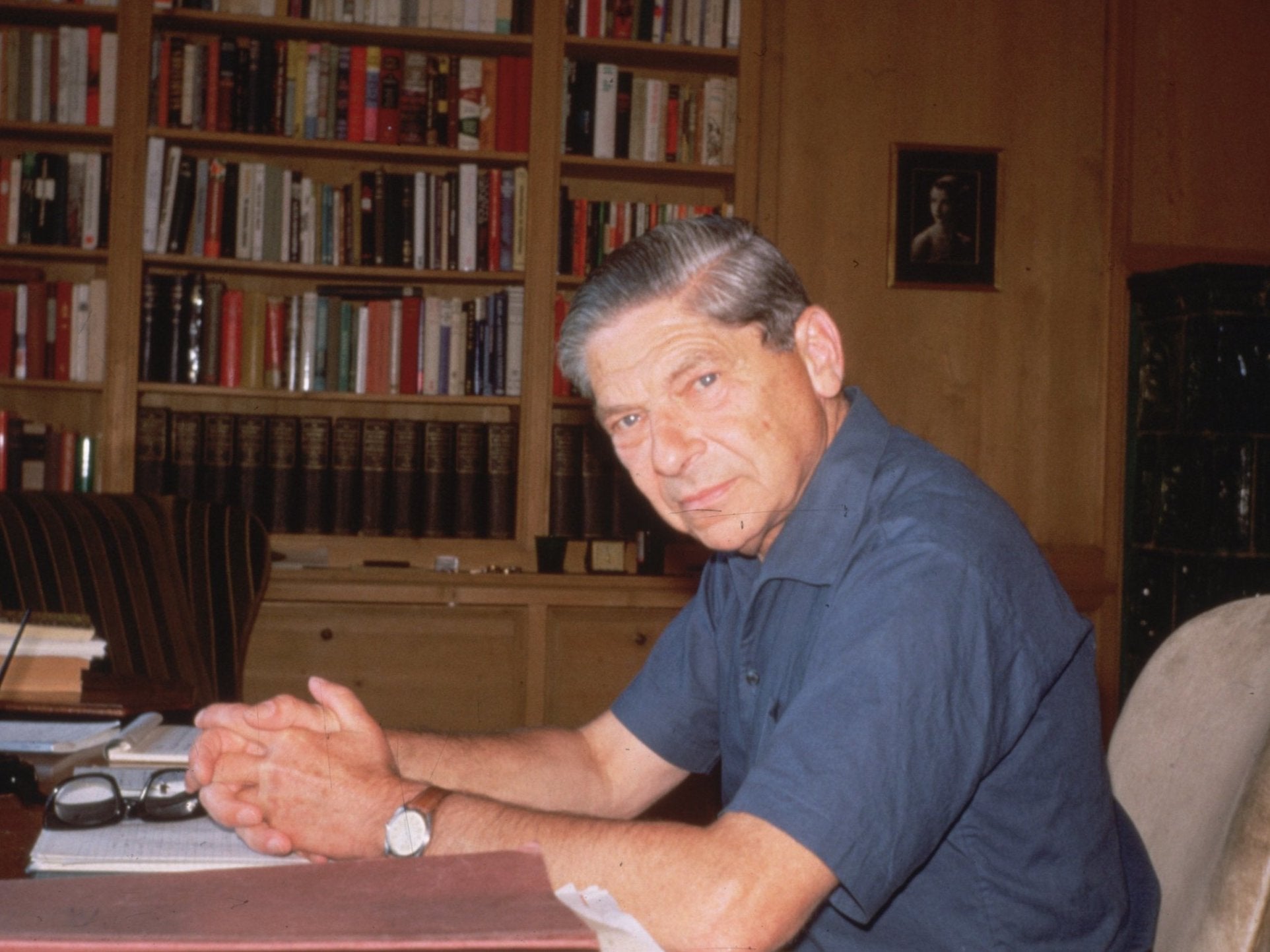

Indeed, the most upsetting interview I have carried out in my career was for The Independent with Jill Craigie, a notable film maker as well as being the wife of the former Labour leader, Michael Foot. It had emerged that many years earlier she had been raped by the acclaimed novelist Arthur Koestler.

A biography of Koestler by Professor David Cesarani in 1999 had revealed him as a serial rapist and disclosed how one of his victims had been Jill Craigie in 1951. I was the first journalist to speak to Craigie after the publication of the biography, and she described to me in horribly graphic detail, and still in evident distress at the memory, how he had attacked her, while a guest in her home.

It was difficult to listen to, and it was difficult to process, not just because of the disgraceful nature of the episode, but because Koestler’s reputation was bound up with his writing, epitomised by the novel Darkness at Noon, which had had a profound effect on me in my in my teens, exposing as it does the horrors of totalitarianism. How could a man capable of work of such integrity and liberalism also be capable of assaulting and demeaning women? And how should one henceforth regard his novels? .

Students at Edinburgh university made up their minds very quickly, demanding the removal of a bust of Koestler from the university grounds.

Now, once again, 20 years or so after my interview with Craigie and the unmasking of Koestler, the question of how much we should separate the art from the artist is as topical as it has ever been. As are the inconsistencies. Indeed, those inconsistencies abound. Let us not forget Roman Polanski, still in possession of an Oscar, still acclaimed by many of his peers, yet guilty of a particularly vile act of rape and sodomy against a 13-year-old girl.

As Spacey comes to terms with the fact that he will probably never work again, he can ponder with the rest of us this lack of consistency. Here’s one more example to mull over, concerning an extremely eminent victim of a social media storm, the Harry Potter author JK Rowling.

It was not, of course, for any inappropriate behaviour by her, but for her backing of the casting of the Hollywood star Johnny Depp in the Fantastic Beasts movies, a series of sequels to the Harry Potter films. Depp’s divorce from the actress Amber Heard contained allegations by Heard of domestic abuse. After a series of attacks on her for supporting his casting, Rowling said: “Harry Potter fans had legitimate questions and concerns about our choice to continue with Johnny Depp in the role. The agreements that have been put in place to protect the privacy of two people, both of whom have expressed a desire to get on with their lives, must be respected.”

Had Kevin Spacey expressed a “desire to get on with his life”, would that have satisfied Rowling?

It is not just inconsistency which is disturbing; it is the Stalinist nature of literally writing people out of the script. Can Spacey’s acting really not be divorced from his character? Perhaps time will heal. It certainly seems to have done in the case of Koestler, let alone Gauguin. It is ironic because it could be argued that Koestler is more deserving of a total ban than any of those in the current spotlight of infamy. The reason for that is that Koestler’s work is so linked to personal integrity that it becomes that much harder to swallow when you know that its creator lacked any integrity in some of his personal relationships.

It is hard to ignore revulsion at a personality defect so marked that it can harm, degrade and traumatise fellow human beings. But ignore it one must, I would argue, when it comes to a work of art

But, why is it that we do not make equivalent judgements when it comes to the visual arts? Gauguin is revered as a key figure in the history of modern art. Also revered, of course, is Caravaggio, an undisputed Old Master, and a murderer of an innocent acquaintance, which turned the artist into an exile and outlaw. He too can be viewed with impunity at the National Gallery.

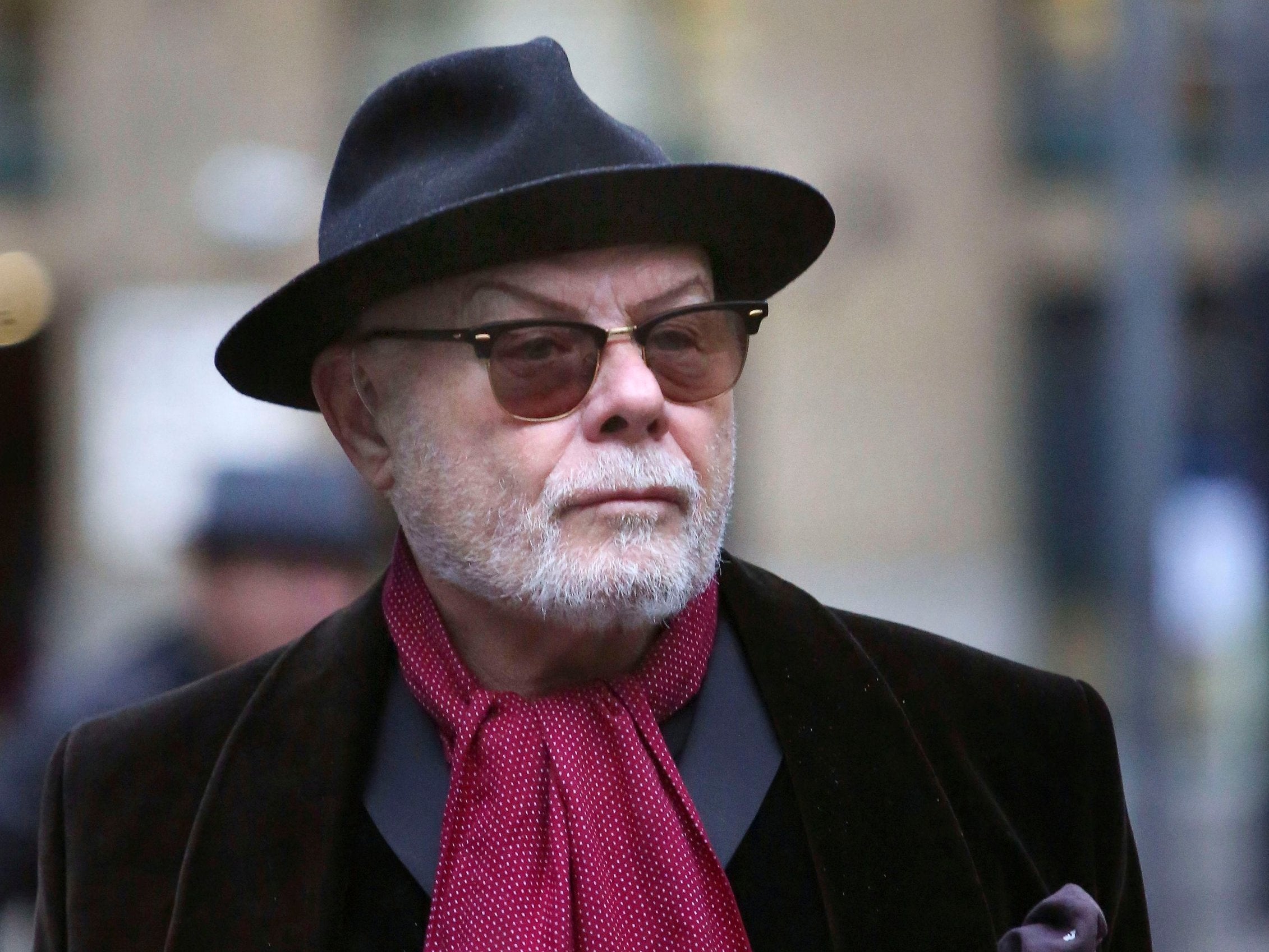

Could it be then that the passing of time is a factor in how we make these judgements? The sins of 100 years ago and more quite simply weigh less heavily on our moral compasses than those of contemporary figures? Rolf Harris and Gary Glitter are manifestly lesser artists than those hitherto mentioned (though that in itself is a curious reason for making a moral judgement) but we can be sure that those two convicted paedophiles won’t be appearing on radio playlists in the near future, probably not in our lifetimes

But if one can listen to Britten’s Peter Grimes with a clear conscience and congratulate oneself on appreciating a Gauguin exhibition, why should one feel a shudder in listening to Bad and Dangerous or watching an old House of Cards?

It is hard to ignore revulsion at a personality defect so marked that it can harm, degrade and traumatise fellow human beings. But ignore it one must, I would argue, when it comes to a work of art. It is quite understandable that one does not want to see the work’s creator, as the Edinburgh students did not want to look on the image of Koestler. But appreciating the finished work is not an endorsement of the person who created it.

We can, as seems to happen now, write known abusers, and even alleged abusers, and their work out of history. Or, we can judge a work of art as an entity in itself and put the flawed, even criminal creator out of mind, but at the same time deprive known abusers of the opportunity to make any more art. Or, we take the view that once a work is created, its creator is irrelevant. Judge the art, not the artist.

Having said that, to put actors, comedians, directors, musicians with chequered pasts before the public and pay them well for it does seem to condone their crimes or alleged crimes

But their previous work, work that was acclaimed before they became subjects of infamy, should still be accorded the same critical judgement as it was at the time. Spacey’s Oscar-winning performance in American Beauty remains an excellent performance in Sam Mendes’s excellent film. Michael Jackson was once accorded the title King of Pop, so his work must have had merit. We surely have to be consistent in respect of our own critical judgements already made.

Kevin Spacey is unlikely ever to work again. Except by the most devoted fans, Michael Jackson will never again be regarded with affection. Johnny Depp will work, but his reputation is tarnished. Artists are often flawed, some are distasteful, some are clearly criminal. But none of that excuses hypocrisy in the viewer and listener. Great art by flawed artists remains great art, and, crucially, critical judgements we have made in the past are still subject to those same critical criteria, even if we now feel revulsion at their creators.

It’s hard and it’s uncomfortable to have to separate the art from the artist. But if we don’t, we are hypocritical about our own critical judgements, write people’s achievements out of cultural history, and behave with remarkable inconsistency about which art is deemed ‘acceptable’.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks