The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

What a message in a bottle from 1939 tells us about the modern world's treatment of immigrants

The rejection of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany on the SS St Louis was later described as having given Hitler 'the green light for the Final Solution'. Adam Lusher reports

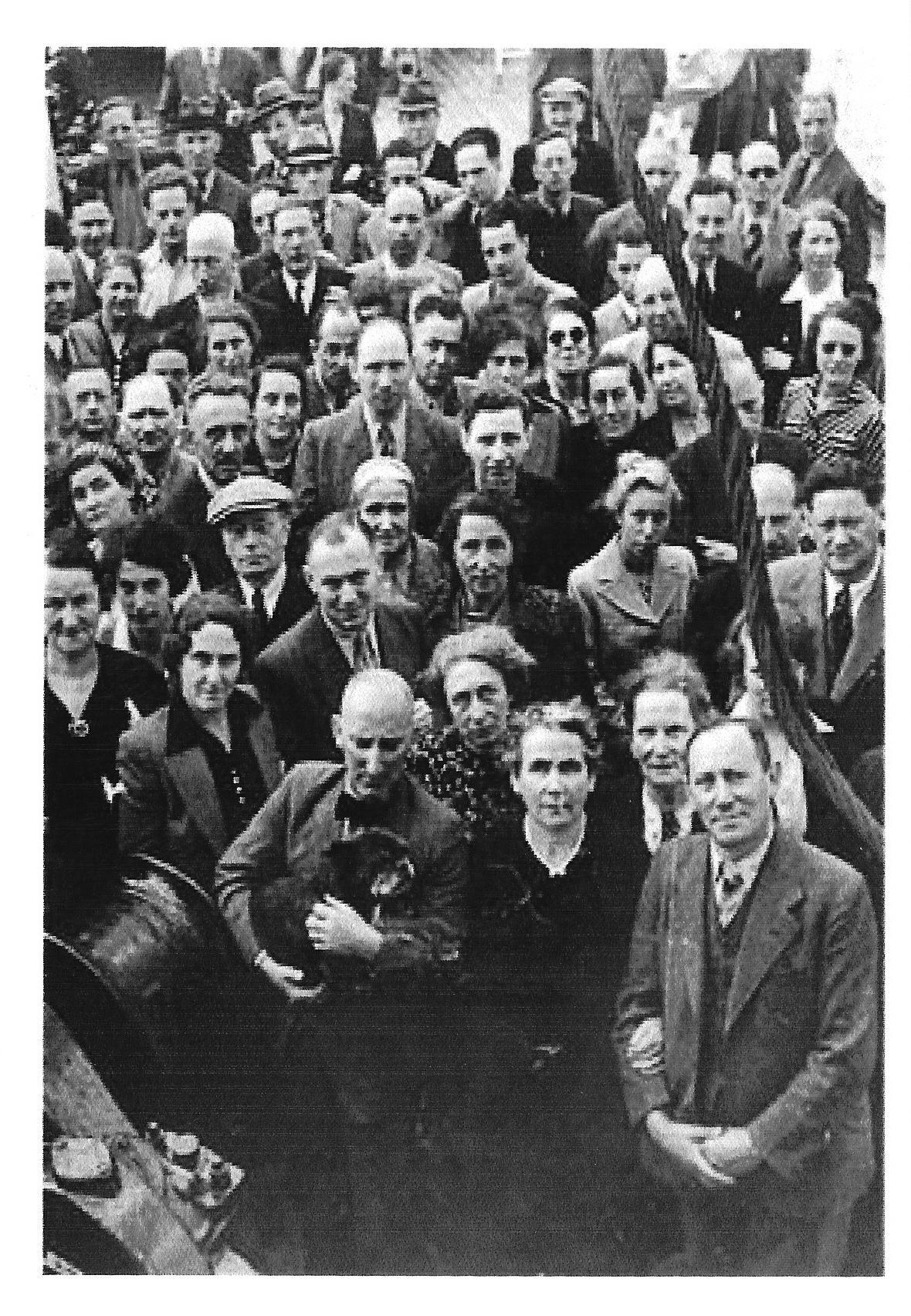

They would come to call it the voyage of the damned: 936 men, women and children, their only ‘crime’ to have been born Jewish, crammed onto a steamship in a desperate attempt to flee Nazi Germany, but denied asylum wherever they turned.

The shunning of the refugees on the SS St Louis would later be remembered as a “green light for the Final Solution”, the spurious ‘justification’ Hitler was seeking so he could claim that extermination rather than emigration was the only way to solve Germany’s “Jewish problem”.

The ordeal of the passengers would in 1976 be turned into an Oscar-nominated film, Voyage of the Damned.

But in June 1939, Richard Dresel, 42, cloth trader, refugee, and father of the youngest passenger on the ship – a six-month-old baby girl called Zilla – had no such means of mass communication at his disposal.

Instead, as the ship steamed away from the safe haven of Havana, having being rejected by the government of President Frederico Bru of Cuba, Mr Dresel resorted to a much older method of communicating his distress.

He threw a bottle into the sea, containing a scrap of paper with his plea to the Cuban leader: “Please help me President Bru or we will be lost."

It is not known if President Bru ever got to read the message. What is known, however, is that rather incredibly it turned up at a car boot sale in Bath, England, in 2003 - minus the bottle and tucked into the pages of Voyage of the Damned, the 1974 book that inspired the 1976 film.

Mr Dresel’s daughter Zilla, by then living in Gosforth, Newcastle, arranged for the message to be donated to the Wiener Library for the Study of Holocaust and Genocide, in London.

And on Wednesday, by the altogether more modern means of Skype, Zilla, who survived to become an 80-year-old grandmother, will ‘attend’ – in a virtual sense – a ceremony where Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau formally apologises for his country’s refusal to accept the refugees of the St Louis.

“It’s a very nice gesture,” says Zilla, who now goes by her married surname of Coorsh.

But it occurs at a time when next door to Canada, President Trump of the US drops dark hints about “unknown Middle Easterners” infiltrating a caravan of immigrants coming from South America, and suggests his soldiers might shoot if any of them throw rocks.

On her side of the Atlantic, Mrs Coorsh worries about the resurgence of antisemitism in her adopted country of England, and sees far-right anti-immigrant parties on the rise throughout Europe.

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses,” says the youngest survivor of the St Louis. “It doesn’t work in times of need, does it?

“It didn’t work for us and it’s not working for those poor people in South America.

“The world has become a very cruel place.”

“It would be wonderful if this Canadian apology made some difference to the rest of the world,” Mrs Coorsh tells The Independent. “But with the way things are at the moment, it’s difficult to remain optimistic.”

Mrs Coorsh compares the modern demonisation of Muslims to the past – and in some cases present – stigmatisation of Jews.

“I feel so sorry for them, being lumped together with a tiny minority of fanatics.”

And she deplores the way Donald Trump has sought to suggest that hidden among the South American migrant caravan are criminals and “Middle Easterners” with implied sympathy for Isis.

“Trump says there are criminals among them,” says the grandmother-of-four. “Perhaps there are. Maybe there were some criminals on the St Louis – but then, as now, the vast majority were normal people, like a mother and father with a six-month-old baby girl.”

“People should put themselves in the position of those trying to reach America and consider how desperate they must be,” she adds. “It is not an easy journey they have undertaken. They would have to be absolutely desperate to want to do it.

“Their situation might not be as acute as ours was, but the lives and livelihoods of their children depend on them reaching a place where they can at least try to earn a living.”

As for her own journey, the full horror of the Holocaust might not have been imaginable to the outside world in 1939, but there was no doubting that the situation of German Jews was already, to use Mrs Coorsh’s word, “acute”.

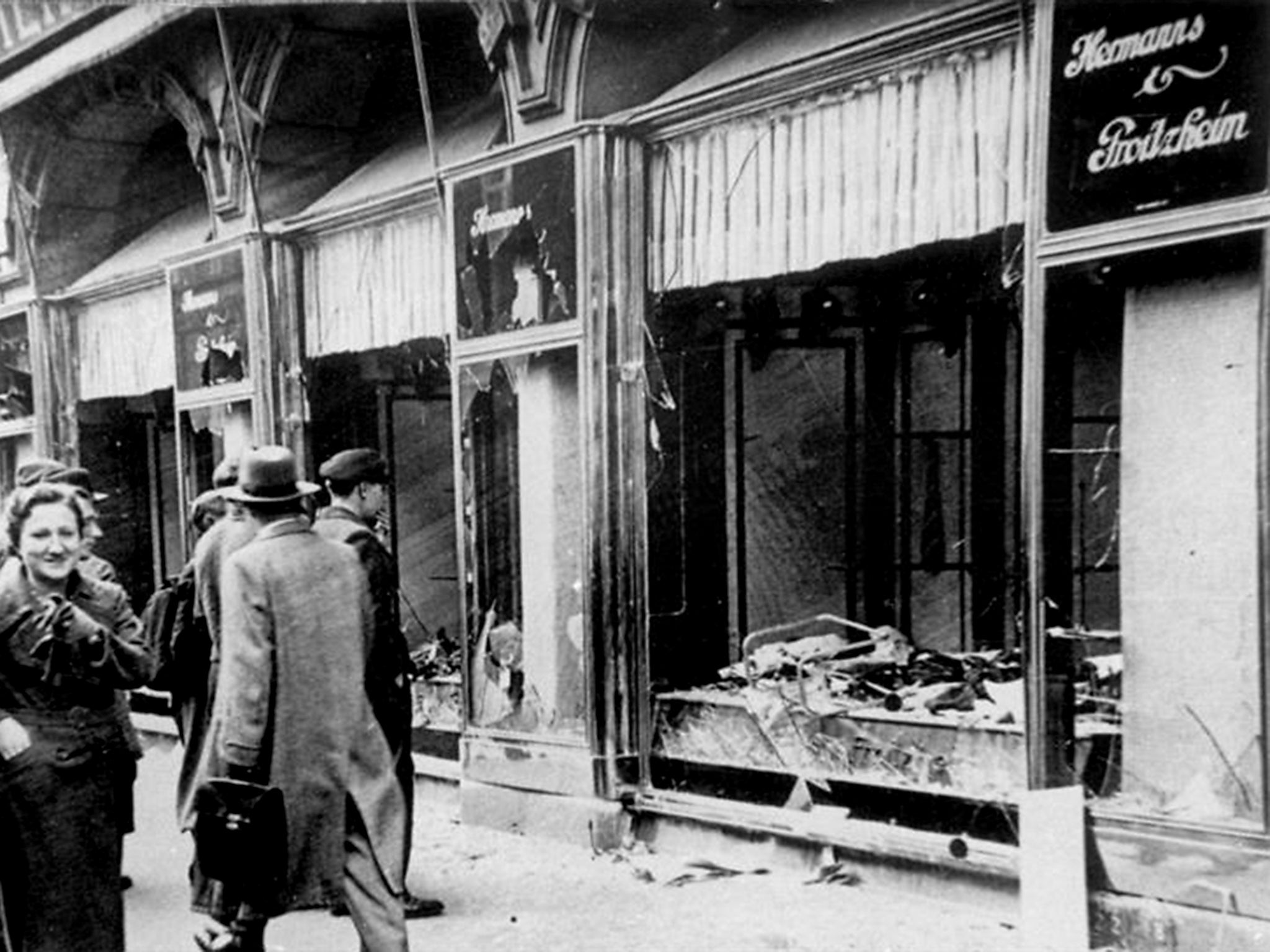

A week before Zilla was born, in November 1938, the Nazis launched Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, an orgy of destruction of Jewish shops, homes and businesses.

Richard Dresel and his older brother Alfred went into hiding to avoid being among the 30,000 Jewish men arrested by the Nazis.

Zilla’s 27-year-old mother Ruth returned home with her newborn baby from the Jewish hospital in Breslau to be told by neighbours that men had come to the house looking for her husband.

When the SS St Louis, a steamship of the Hamburg-American Line, left the German port on May 13 1939, Richard, Ruth, Zilla and Alfred Dresel were on board.

As Voyage of the Damned authors Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts made clear, the trip had been approved by the Nazi high command over a convivial lunch at the Hotel Adlon in Berlin.

For Hitler’s propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels the voyage of the St Louis could be used to show that the gracious Nazi government was treating the Jews well and even allowing them to leave if they wanted.

On Friday May 26, as the ship passed along the Florida coast, some excited St Louis passengers sent telegraph cables to anxious loved ones saying “Arrived safely”.

At about dawn on May 27, the SS St Louis anchored off Havana. The ship’s orchestra struck up Freucht euch des Lebens, ‘Be Happy You’re Alive’.

At first some passengers thought they hadn’t entered the harbour itself because it was too shallow for a ship the size of the St Louis.

Then the truth dawned. They weren’t being let in.

A week before the St Louis sailed, President Bru had issued Decree 937 making entrance to Cuba conditional on the written authority of two government ministers and the receipt of a $500 bond.

With Cuba in a time of need, economic depression made many of its citizens regard Jewish immigrants as competitors for their jobs.

News of the St Louis’ impending departure from Hamburg had led, on May 8 1939, to the largest anti-Semitic demonstration in Cuban history, with former president Grau San Martin’s spokesman urging protesters to “fight the Jews until the last one is driven out”.

Faced with such anti-immigrant hostility, President Bru was in no mood to agree to the plea of a refugee Jewish cloth trader, even if he did read Richard Dresel’s message.

On one occasion, disturbed during his siesta by the sound of St Louis’ siren drifting across to the Havana shore, he sent word that passenger “demonstrations” would not improve matters.

Only 28 of the 936 passengers were allowed by the Cuban government to disembark. A 29th passenger tried to commit suicide and was rushed to hospital in Havana on May 30.

The rest, however, were still on board when on June 2 President Bru officially ordered the St Louis to leave Cuban waters.

By the morning of June 4 the refugees of the St Louis came within sight of Miami.

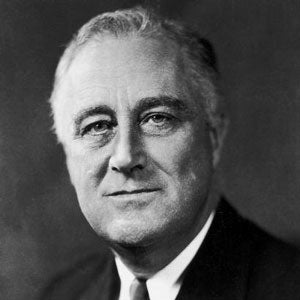

Captain Gustav Schroeder cabled President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asking for help.

Roosevelt never replied.

An April 1939 opinion poll had suggested that 83 per cent of Americans opposed any loosening of immigration controls.

Roosevelt was due to run for re-election in 1940.

Before the St Louis even came within sight of Miami, the US government had decided to stick to the letter of the 1924 Immigration Act which set yearly quotas for immigrants from each country.

Because of the fear caused by Hitler, the annual quota of 25,957 immigrants from Germany had already been filled.

On June 6 1939 Captain Schroeder decided he had no option but to turn the St Louis back in the direction of Europe.

On November 5 1940 Roosevelt was comfortably re-elected US president.

And then it was Canada’s turn to reject the refugees of the St Louis.

On June 7, with the St Louis just two days’ sailing away from the coast of Canada, more than 40 prominent Toronto citizens publicly asked Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to take pity on the Jewish refugees.

But Canada’s justice minister was “emphatically opposed” to admitting them and Frederick Blair, the head of the department which decided Canada’s immigration laws, declared: “No country could open its doors wide enough to take in the hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who want to leave Europe: the line must be drawn somewhere.”

Mackenzie King was inclined to agree with his ministers. The previous year, he had confided to his diary: “We must seek to keep this part of the [North American] continent free from unrest and from too great an intermixture of foreign strains of blood … I fear we would have riots if we agreed to a policy that admitted numbers of Jews.”

And so, as Justin Trudeau will acknowledge, Canada became the third country to deny sanctuary to the refugees on the St Louis.

It was a rejection that worked perhaps to Hitler’s advantage. Goebbels directed his propaganda machine to ask how the rest of the world could criticise Nazi treatment of Jews when all these other countries didn’t want them in their territories either.

On the day that Canada refused sanctuary to the ship’s passengers, German radio stations announced: “Since no one will accept the shabby Jews on the St Louis, we will have to take them back and support them.”

How now, these reports seemed to imply, could Germany rid itself of its “Jewish problem”?

Small wonder, perhaps, that at a 2011 commemoration event, Rudolph Jacobson, who had boarded the ship as a six-year-old, urged those present: “Just remember the significance of the St Louis voyage. It gave the Nazis the green light for the Final Solution.”

“I think there’s a lot of truth in that,” says Mrs Coorsh. “Although in one sense I really don’t think Hitler felt he needed a justification for his extermination plans.

“But yes, I think he wanted to show that he was not alone, that the Jews weren’t welcome anywhere, and we really were [regarded as] ‘subhuman’.”

On June 17 1939, the weary immigrants found themselves back in Europe.

But they were in Antwerp, Belgium, not Germany.

At almost the last minute, a deal had been struck whereby Britain would take 288 refugees, France 224, Belgium 214 and Holland 181.

The generosity of these European countries, however, can be exaggerated.

Voyage of the Damned recounts how as the national representatives discussed which individuals would make up their share of the refugees, there was thinly disguised competition to get those with the lowest numbers on the waiting list for the US who would leave for America the soonest.

“We tried to get people we could, so to speak, get rid of quickly,” the Dutch representative admitted.

Although no-one in the St Louis ballroom knew it, this was also an unwitting exercise in separating those who would face Hitler’s death squads in Nazi-occupied Europe from those who would make it to the relative safety of Britain.

It is estimated that 254 of the St Louis refugees were later murdered in the Holocaust.

Richard Dresel was the only passenger who got to decide where he and his family would go.

Mrs Coorsh explains: “When everyone gathered in the St Louis ballroom to be told their allotted country, my father didn’t hear his name called. So he went to the purser and said, ‘You haven’t called my name’.

“To which the purser replied: ‘Well, where would you like to go?’

“My mother wanted to go to France. She had been told, ‘It will be wonderful. The weather’s better. The food’s better.’

“But my father was adamant. He admired the English, and he thought that with the sea between it and Germany, England would be safer.

“He chose England, even though his brother Alfred was going to France.”

And so on June 21 1939 the Dresels were still on board when the St Louis docked at Southampton.

The ship was greeted by a chorus of whooping ships’ sirens and firefighting boats sending jets of water high into the air. The port was rehearsing for a visit from King George VI, who was due to arrive the following day.

The Dresels survived to open their own clothes shop, Dresto Modes, in Bishop Auckland, County Durham.

It prospered and became a small chain of five shops which Mrs Coorsh and her husband helped run.

Her uncle Alfred was not so lucky. Three years after leaving the St Louis, in 1942, the 47-year-old was picked up by the authorities in Nazi-occupied France.

In one of the last postcards he was allowed to write, from a French internment camp, Alfred reassured Richard, Ruth and Zilla, “My dear ones, peace has to arrive one day, and then we will hopefully all be together again.”

It was not to be. Later that year, Alfred was deported to Auschwitz.

Mrs Coorsh never really spoke to her parents about what happened on the voyage of the St Louis and during the Holocaust that followed. She only learned about the “heartbreaking” message in a bottle when it was found in 2003.

By then her father had been dead 25 years, having passed away in 1978, aged 81, without ever having told his daughter about what desperation forced a rejected, frightened immigrant to do.

Perhaps, says Mrs Coorsh, she might have asked him once about the St Louis. But only once.

“You learn as a child,” says Mrs Coorsh, “Not to ask a question again when you see how upset that question makes your parents feel.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks