Google Translate will never outsmart the human mind – and this is why

As someone who is paid to teach students to translate literary texts, I tell them, if you want to be a good translator, don’t translate – you have to live it

I guess I should never have signed up to be a simultaneous translator (or interpreter) – in both directions – at an EU-sponsored conference. The silver lining of Brexit is that I will probably never be called on again to translate not just a rapid-fire French speaker with a penchant for hazy abstraction into passable English, but also shortly afterwards (and this is where I came a cropper) to render the gist of an account of musical culture in Northern Ireland for the benefit of the French-only speakers in the audience. I thought I had done rather well to turn “fife and drum band” into “orchestre populaire”, except that the Belfast man then proceeded to explore the nuts and bolts of the drum side of the equation, which was awkward given that I had temporarily forgotten the French for “drum”. I stumbled around for a while, stuck on “tampon”, until some dusty circuit in my brain finally lit up and I was able to refer to the art of the “tambour”. This was a few years back and I can’t help thinking – if only I had had my phone to hand with Google Translate online I could have saved myself a nasty moment. On the other hand, I probably wouldn’t have received the ironic round of applause. It was simultaneous translating, but with built-in jet-lag.

In terms of human fallibility, the only thing that tops that is the time I was asked, one lunchtime, to produce a prose translation of an ancient French carol for a well-known college choir. I turned the job around as requested – fait accompli – only to hear a schoolboy howler being broadcast to a billion or so listeners a short while later. I was reminded of these (and other fiascos) while reading the many fascinating takes, alternately poignant and hilarious, on the pleasures and perils of “the superhuman task of translation” – as Primo Levi calls it – in Crossing Borders, a new collection of stories and essays published by Seven Stories Press in New York.

Every now and then I am reminded in the latest online hype (probably sponsored by Google, now I come think of it) about how wonderful – so “deep” in the jargon – Google Translate has become, that I think that I might as well give up teaching translation to anyone and move over and just let the machines do it. They won’t forget “tambour”. And they can’t do much worse with that carol either. In these moments, it seems to me that merely human translators, like waiters in a Yo! Sushi bar, are probably doomed. Pay them off (you don’t have to pay them that much anyway) and tell them to go and do something useful with their lives.

Then I stop to check what Google Translate actually comes up with, as soon as you go beyond the fife and drum band or asking the way to the airport, and try it out on some reasonably high-level discourse. And I realise that translators shouldn’t be throwing in the towel just yet. Because translating like a machine is exactly what you shouldn’t do.

Oddly enough, I get paid to teach students how to translate mainly literary texts. Which I think of as basically impossible. It’s like paying someone to teach tight-rope walking who assumes you are just naturally going to get blown off in a high wind or slip and fall into a void of pure nonsense, garlanded with obscenity. I can’t even translate jokes. For example, I have spent years puzzling over Groucho Marx’s classic one-liner, “You’re only as old as the woman you feel.” I once offered this as an example of how translation is mission impossible in an article written in English. A few months later a friend sent me a translation that had appeared in a Paris magazine. Here is the Marxian gag, French-style, translated back into English: “A man is only as old as the woman he can feel inside of himself trying to get out.” Good try, mon pote! It’s not funny, but at least it’s an attempt to interpret the original, even if in the light of the wrong zeitgeist (1950s American sexist humour rendered into bien-pensant millennial positive thinking). Plus, now I think of it, that magazine still owes me.

Google is often adequate, and in so many languages too, but only in the way of a particularly uninspired apprentice translator. I once picked a book off a shelf in a bookshop because I was attracted by its zany title: Whatever. It was only when I saw the name of the author and leafed through it that I realised that it was a book I already knew well in French: Michel Houellebecq’s Extension du domaine de la lutte. After initially saying to myself, ‘What kind of crazy translation is that?!’, I saw that, in fact, it’s a stroke of genius. The original title is deliberately turgid to the point of being interesting (and may, in fact, be a homage to the sociologist Auguste Comte) and the translator had achieved what is surely the only real point of a title, which is to make you pick up the book in the first place. Google’s “Extension of the field of struggle”, while technically permissible, has the opposite effect.

Perhaps it’s obvious that a machine is going to struggle with the resonance and complexity of, say, Victor Hugo or Jean-Paul Sartre. So I thought I’d start with an easy one. One of the first sentences I (like many others, I suspect) can remember learning, probably around the age of 3 or 4, before even going to school, is this: “The cat sat on the mat.” Google Translate suggests: “Le chat s’est assis sur le tapis.” Again, good try Google. But try remembering that 50-odd years from now. You could argue about the tense and even the choice of noun (is “mat” really “tapis”?) But the main point is that Google can’t see that it’s a mnemonic, made up of rhyming monosyllables, and that the best solution is to change the species, which is what French does, in the children’s rhyme, “Il était une souris qui mangeait du riz sur un tapis gris…” (There once was a mouse who was eating rice on a grey carpet…) Now that I can remember. (And it goes on, “Et sa maman lui dit, ce n’est pas gentil de manger du riz sur un tapis gris.”)

A machine translator does nothing but translate. This is how it sees its job. As a form of tautology or equivalence. One set of words is exchanged for another set of words. One code is replaced by another code. But, you will say, isn’t that what translation is? This is what I tell my class: if you want to be a good translator, don’t translate. Only bad translators translate. You have to live it. If you want to translate George Sand or Flaubert or Tolstoy, for the duration of that translation, you have to be George Sand, you have to be Flaubert, but reborn, as if they really spoke English, now.

There is, at the core of the translation process, a mystery, an almost mystic transcendence. There is no direct equivalence of one language to another. It’s not just that certain words (eg hygge in Danish) cannot be satisfactorily translated: none of them can. This is what happens in a serious translation. You read a sentence. But – and this is the point that Google tends to miss – those squiggles on the page actually represent something other than words, they are not reducible to mere information, ones and zeroes. So you convert them into something other than words. Something like ideas, imprecise though that term is. Or feelings. You infuse the words with your own memories, your experiences, your fears and desires, things you have done or seen or fantasised about or heard once in a song on the radio that you will never hear again. The experience of having been born and being doomed to die also get in there. You – for a brief impossible moment – become Tolstoy, and then and only then can you re-express what was said somewhere else in some other time in your own words in your own time. And, inevitably, of course, you still get it wrong.

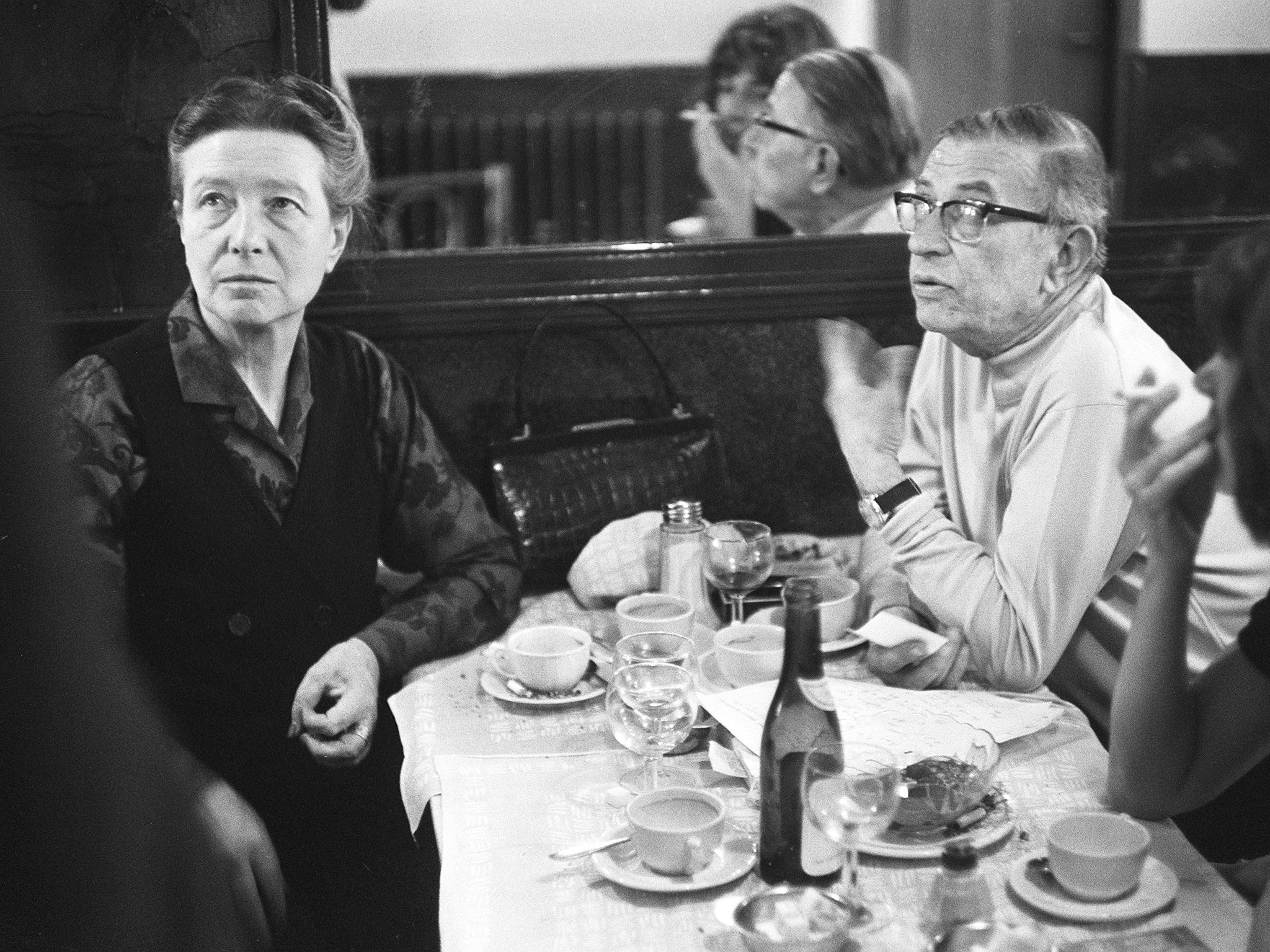

Translation is like the archetype of all human relations. We never get it quite right when it comes to understanding other people. At the same time, we ought to try. Being human is an advantage when it comes to translating other humans. Consider this, for example. Simone de Beauvoir, the philosopher, writes in one of her memoirs, “La religion ne pouvait pas plus pour ma mère que pour moi l’espoir d’un succès posthume.” Google suggests: “Religion could no more for my mother than for me the hope of a posthumous success.” Google here makes no (or little) sense. Mainly because Beauvoir, in her elegant way, is being elliptical and economical. To spell it out (a little laboriously, I admit), she is saying, “The afterlife promised by religion was of no more comfort to my mother than the hope of a posthumous literary success was to me.” It helps if you know Beauvoir was an atheist of course. And also if you have a rough idea of the kind of salvation on offer from religion. If all you can see is a bunch of words, then you’re stuffed.

Or what about this? A touch more obscure and archaic, but not unintelligible. From an essay written several centuries ago by Catherine des Roches (or Kate of the Rocks), who really wanted to be an intellectual rather than have to hang out at balls and parties in pursuit of “courtly love”: “quant à moy, qui n’ay jamais fait aveu d’aucun serviteur, et qui ne pense point meriter que les hommes se doivent asservir pour mon service…” Google proposes the following: “as to me, who has never made a confession of any servant, and who does not think it merits that men ought to enslave me for my service…” This is semantically and grammatically challenged, ie complete garbage. I hate that “me who has”. So clunky. How can “enslave me for my service” ever be right? Here is my version (entering, for a moment, into the mind of a 16th-century #Metoo poet): “And what of me? Not currently in a relationship, nor ever really had one, and don’t really want one either if we have to go through this silly business of a star-struck lover pledging to be my servant.” It’s far from perfect, but at least it sounds like a human being (who may have acquired a FaceBook account).

I admit that every now and then I suspect a mischievous student of putting a Google translation in front of me just to keep me on my toes. Machine translators are a relatively recent invention. But machines have been with us for millennia. Technology is a necessary supplement to humanity. But tools and machines are cold dead things, they are essentially inert. We have to switch them on. All of literature and philosophy and expressive language is a protest not against the machine per se, but against people behaving as if they were machines – incapable of making a judgment call in particular circumstances (which circumstances nearly always are). The human mind, we are implicitly saying, is something other than a constellation of metal or silicon. Similarly, good translation is not translation – exchanging a random collection of information for another – it’s more like a form of resurrection. Translation gives you not just the meaning of a text, it gives you the heart and soul of its author. Its secret message is always, “I am not a robot.”

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’, and teaches at the University of Cambridge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks