Inside the fight for LGBT+ rights across the Commonwealth

Bound together by optimism and Britain's colonial legacy of homophobia and white supremacy, a group of Commonwealth LGBT+ activists gather in Mauritius. Can they find new, intersectional ways to tackle systemic discrimination and violence? Louis Staples went to find out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.American author Thomas L Friedman once wrote: “Pessimists are usually right and optimists are usually wrong, but all the great changes have been accomplished by optimists.” When the news often seems more bleak than positive, this is a mantra I find myself referring to often. But as I arrive in Mauritius – an Indian Ocean island nation known for its beaches, mountains, rainforests and reefs – for a gathering of LGBT+ activists from across the world, Friedman’s mantra has never felt more relevant.

Mauritius is the backdrop for the Commonwealth Equality Network’s (TCEN) global conference, a unique gathering that brings together LGBT+ activists from across the Commonwealth – a family of 53 member states, almost all of which are former territories of the British Empire. Established in 2013, TCEN is a network of 51 LGBT+ organisations working to challenge inequality and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity throughout the Commonwealth.

Such a network is necessary. The Commonwealth includes nations that are among the most challenging places in the world to be LGBT+. In fact, half of the 70 countries that criminalise homosexuality worldwide are Commonwealth members. The death penalty is still enshrined in law in Pakistan and lengthy sentences for gay sex still remain in many African nations such as Uganda and Caribbean islands like Barbados and St Lucia. Brunei – which recently announced plans to punish gay sex with death by stoning, before suggesting that this penalty will not be enforced after international backlash – is also a member of the Commonwealth. Though conversely, in Commonwealth countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malta and, of course, the UK (excluding Northern Ireland), same-sex marriage is legal.

The primary questions facing activists as they arrive in Mauritius for a week of planning, joint advocacy and strategising often seem insurmountable. How do you stop people from hating each other for who they are? How, even when the forces of patriarchy, religion and politics are against you, do you improve the lives of LGBT+ people? How do such different nations, bound together by a history of colonial white supremacy, work together in a way that amplifies its most marginalised members?

In many ways, Mauritius is the ideal place for these discussions to happen. Beyond its paradisiac scenery lies the truth that consensual homosexual sex acts – both anal and oral sex between two men or two women – are illegal. Sodomy is punishable with up to five years in prison.

“Mauritius it’s a very conservative society,” explains Mauritian LGBT+ activist Anjeelee Kaur. Anjelee began working at Collectif Arc En Ciel – the island’s biggest LGBT+ organisation – in 2018, but has been committed to equality from a young age. “When I was in school, I was always saying that we should be giving equal rights to people, especially LGBT+ people. My grandparents raised me to treat everyone with respect and equal value. But I never really got to act what I was saying. This is the perfect opportunity for me to walk the talk.”

The history of Mauritius begins with its discovery by Arabs, followed by Europeans and its successive colonisation by the Dutch, French and British. Mauritius became independent in 1968, but remains heavily influenced by India and South Africa – two Commonwealth nations.

Applying to host TCEN’s global conference was the first thing Anjeelee did when she began working at CAEC. “I think it was very important for us because at that time, we were waiting for the India decision,” she explains. In September 2018, India’s Supreme Court ruled that gay sex should no longer be a criminal offence, consequently liberating one billion Commonwealth citizens from the criminalisation of homosexuality. “Mauritius is a melting pot of cultures of people from Africa, Europe and Asia, but we don’t have strong links with all these nations around the world. Participating in TCEN and hosting activists from across the Commonwealth is the perfect opportunity to meet LGBT+ people working in these places and learn from how they’re doing things.”

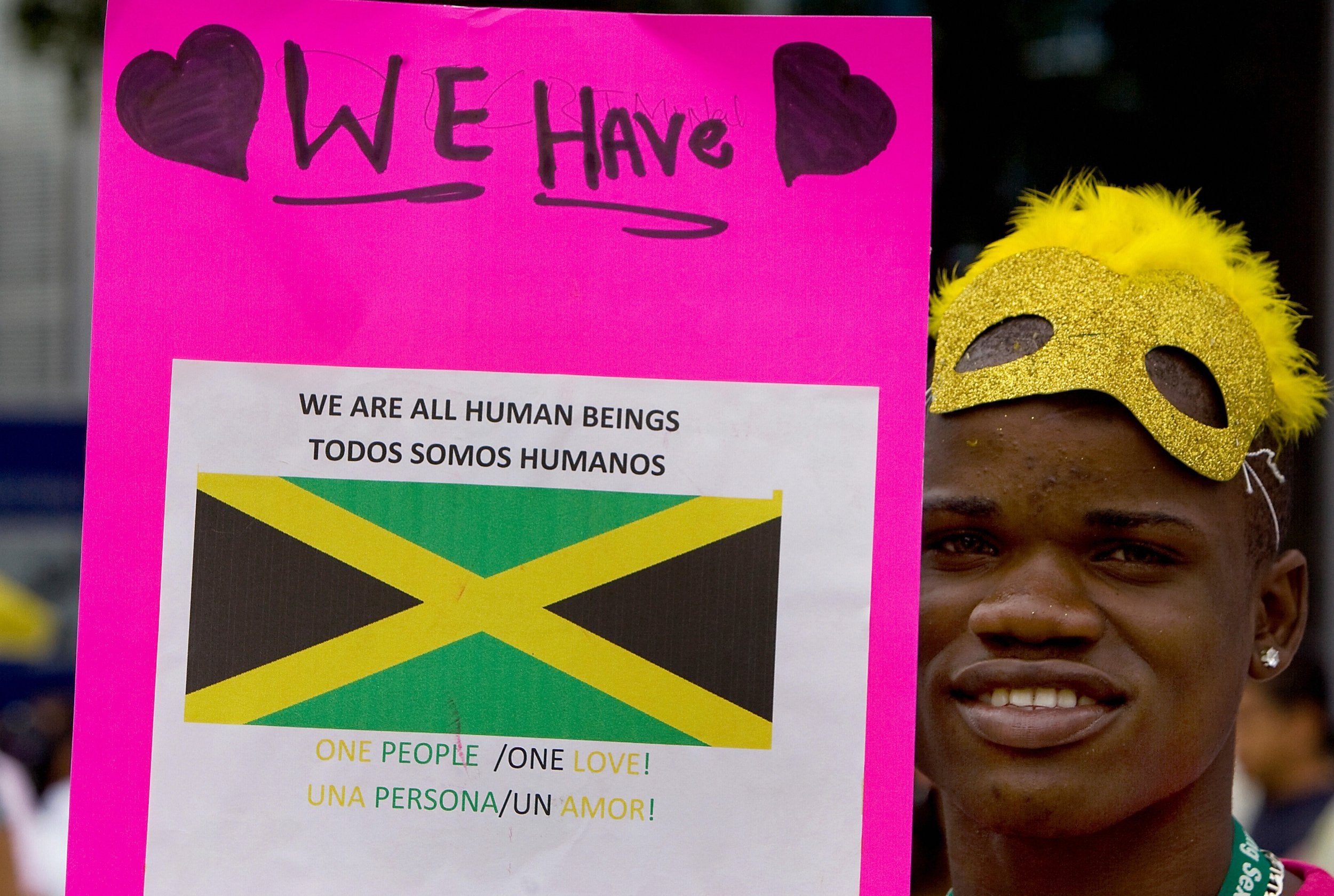

The Commonwealth is an unlikely but fascinating forum for advancing LGBT+ rights. All six regions – Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and the Pacific – are represented on the TCEN’s management committee, proving that LGBT+ people – and LGBT+ activists – are found everywhere. Meeting in Mauritius are representatives from 50 organisations from 40 countries, including Tonga, Rwanda, South Africa, Jamaica, Malaysia and Australia.

Anjeelee believes that this group of activists are bound together by a shared tenacity. “As an activist you have to think two steps forward. Either your lives are in danger or you’ll be having a low that came out of nowhere. Every time you have to anticipate what’s going to happen next, so that you can better strategise to limit the damage.”

Each person I speak to has a different story that has brought them to LGBT+ activism. Many are titans of the global LGBT+ rights movement who have achieved incredible things.

Tongan activist Joleen Mataele’s fight against religious fundamentalism and intolerance in Tonga was recently portrayed in the film Leitis in Waiting. Frank Mugisha is one of the most prominent LGBT+ activists in Uganda and has won the Robert F Kennedy Human Rights Award for his activism.

Sometimes there was no food at home so we had to find ways to navigate survival. I had lots of resistance everywhere: at home, the school and the church

Belizean activist Caleb Orozco co-founded the only LGBT+ advocacy group in his country and was the chief litigant in a case that resulted in the repealing of Belize’s anti-sodomy laws in 2016. Fabianna Bonne also led the campaign for decriminalisation in Seychelles which finalised in the same year. Linda Baumann is one of the most well-known, visible lesbians in Africa. The list goes on.

For this group, activism is personal. South African activist Steve Letsike remembers her first forays into activism as a child, where she challenged her school’s sexist uniform policies. As a masculine presenting girl raised by her grandparents, barriers were everywhere. “Sometimes there was no food at home so we had to find ways to navigate survival,” she explains. “I had lots of resistance everywhere: at home, the school and the church.”

Steve developed her own brand of resistance, becoming active in the ANC, South Africa’s ruling political party. Two decades on, she runs Access Chapter 2, an organisation that promotes human rights and the empowerment for women and LGBT+ people. “I wanted to focus on urban and rural settings, visiting provinces with few LGBT+ organisations,” she says. “South Africa is unique in its own right. Our long history of prejudice teaches us a lot and experiences can vary province by province. Economic issues can create challenges and limit access to services. Culture plays a big role too.”

South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, but most Africans are not afforded such protections. Some activists are risking their lives every day, like Hamlet Nkwain of Cameroonian LGBT+ organisation ADEFHO.

In Cameroon gay sex is illegal. LGBT+ people are not able to speak openly and people suspected of being LGBT+ can be arrested on “suspicion” without evidence. “I have become the victim of violence while protecting people. I’ve been bruised, beaten and hit by glass bottles,” says Hamlet. “I fell while being beaten for protecting people from the police and fractured my jaw. I have a big scar on my back because I couldn’t treat the wound properly because of lack of finance.”

I fell while being beaten for protecting people from the police and fractured my jaw. I have a big scar on my back because I couldn’t treat the wound properly because of lack of finance

Hamlet says that violence is worsening. “You can be in your home and people can come into your house, beat you up, break your bones and steal all your stuff,” he says. “You cannot complain to the police, because instead of helping you, they’ll try to lock you up. When I was hit with a glass bottle, instead of the police coming to arrest those who committed the violence, we were arrested and locked up.” He has also received threats on social media. “I was targeted on social media by someone claiming to be a medical practitioner,” he says. “He kept repeatedly telling me in detail what he’d do to an LGBT+ person if they came to seek treatment.”

There are other Commonwealth states where the law is moving in the right direction, like Trinidad and Tobago, where a ban on homosexual sex acts was deemed unconstitutional in 2018. Trinidadian activist Zeleca Julien knows first-hand about the barriers presented by class, gender and sexuality. “I come from a family of hustlers, of small business and trying to make cash out of nothing. I experience classism in LGBT+ spaces and homophobia and classism in general society.”

Zeleca now runs I Am One, a community-based organisation that seeks to address the needs of gender and sexual minorities in Trinidad and Tobago. I Am One organises the King Show, the first pageant in the Caribbean that showcases stud culture and trans masculinity. Zeleca and her team then launched the regional King conference in Trinidad, which created a space to research and theorise the ideas that came out of the show. “The goal is to collect data on the lived experience of LGBT+ people in the Caribbean,” she says.

Last April, at the age of 28, Zeleca was asked to speak about her experiences as a young, black lesbian woman at the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in London. Every two years at this meeting, leaders, activists, business and civil society representatives from across the Commonwealth come together to reaffirm their common values, address shared global challenges and agree how to work together to create a better future. Opening her speech, she said: “I’m black. I’m a woman, I’m a lesbian and I want to be free.”

Zeleca chose to begin her speech by talking about her story and family. “That was important to me because I’m also black and female, I think that worked with the audience because they could identify with that,” she explains. “Stories humanise people. People think ‘oh we’re actually similar, and we can learn from our difference’.”

Individual narratives such as Zeleca’s are a key tool in the fight against discrimination, but so is confronting the truth of the story behind so many Commonwealth nations still criminalising homosexuality.

It is impossible to untangle the inequalities faced by LGBT+ people throughout the Commonwealth from its history of colonisation and white supremacy. After all, that is the story that binds these nations together. Despite Britain’s newly formed image as a global leader in LGBT+ rights, the British Empire’s role in exporting homophobic laws across the world can’t be understated.

During the colonial period, Britain enforced “decency” and “morality” laws across the Commonwealth that prohibited, among other things, same-sex sex acts. Prior to British colonisation, liberal attitudes towards sex were widely held in areas such as the Caribbean and the Middle East, which are now characterised by Western media as the worst places in the world to be gay. Many of these countries, including Mauritius, Bangladesh and Jamaica, still criminalise homosexuality under the exact laws that were imposed by Britain during the colonial era.

Many Commonwealth nations have decriminalised since then, but countries such as Barbados have updated their laws and continue to criminalise homosexuality.

To expect nations to repeal colonial laws with ease, even in 2019, ignores the complex dynamic created by colonialism. Systemic homophobia in the Commonwealth, particularly in the Caribbean and parts of Africa, creates “cultural resistance” to values that are perceived as foreign and western. “The post-colonial experience of oppression means that people see queerness as something that is foreign or Western, so they immediately want to resist it,” Barbadian activist Donnya Piggott told me. “Caribbean people want to stamp their sovereignty so much that we resist anything that’s Western or forced upon us.”

For many people, LGBT+ is seen as un-Jamaican. There’s definitely a sort of resistance to foreignness in the way in which homophobia plays out in Jamaica

Jaevion Nelson of J-Flag, an LGBT+ organisation based in Jamaica, also identifies this problem. “For many people, LGBT+ is seen as un-Jamaican. There’s definitely a sort of resistance to foreignness in the way in which homophobia plays out in Jamaica,” he explains. “Because Western countries have led the global LGBT+ movement for so long, it has helped to entrench this idea that it’s really a white thing that people are forcing upon us. There’s quite a lot of work to be done so that people can begin to understand that LGBT+ people do exist here.”

British governments have furthered the narrative that homosexuality is white and Western. In 2011, David Cameron suggested that foreign aid to Uganda should be conditional on the country abandoning an attempt to introduce the death penalty for gay sex. Despite being well intentioned, this move was widely condemned in the activist movement for not being in the interests of LGBT+ people on the ground. Such statements are unlikely to be effective in nations that are defensive over their culture after being colonised – despite the fact that, in most cases, these homophobic laws were originally imposed by their colonisers.

So what is the best way for Britain to approach its colonial past with regards to LGBT+ rights?

During her keynote speech to Commonwealth leaders and activists at London’s CHOGM in April 2018, prime minister Theresa May expressed “deep regret” for Britain’s colonial legacy of homophobic laws. The prime minister urged Commonwealth nations to overhaul “outdated” colonial-era legislation that criminalises same-sex acts. May said: “I am all too aware that these laws were often put in place by my country. They were wrong then, and they are wrong now.”

Although May stopped short of an apology, this statement was the furthest any British prime minister has gone to express regret for its homophobia during the colonial era.

Paul Dillane, executive director of UK-based organisation Kaleidoscope Trust, viewed London’s CHOGM summit as a significant moment for LGBT+ visibility. “TCEN can point to many successes from the summit, including Britain grappling with its colonial past,” he explains. ”Theresa May accepted our request to make a statement. She would not have expressed deep regret for those laws had it not been for our advocacy.”

May’s statement was well received by activists. Kenita Placide, executive director of St Lucia-based LGBT+ organisation Eastern Caribbean Alliance for Diversity and Equality, lists May’s statement as one of her highlights from the summit. “We were able to have a number of meetings and also increase participation of activists from around the globe. But one of the highlights for me was the deep regret from Theresa May, because we understand the impact and the struggles of that colonial legacy that has been left behind.”

Not everyone was as positive. In fact, even before the statement, there were voices within the global movement who were sceptical of what an apology would really mean, or what it would change. “It’s two ways for me. I think it’s a very important statement, but it is my view that the deep regret should have actually come off as an apology,” says TCEN’s vice-chair Steve Letsike. “We have a legacy of colonial law that has killed many people, that has compromised many cultures and traditions. They were stolen from people. It’s a serious theft of humanity.”

It doesn’t mean very much for us. I feel that it is easy to express regret for the colonial laws of sodomy. But I would like to hear an expression of apology for all the colonial laws including sedition and slavery

A year on, these reservations are common. “It doesn’t mean very much for us. I feel that it is easy to express regret for the colonial laws of sodomy,” says Malaysian LGBT+ activist Pang Khee Teik. “But I would like to hear an expression of apology for all the colonial laws including sedition and slavery. Because all these legacies are still affecting our countries.”

Given Britain’s colonial past and the real inequalities that still exist because of it, May’s statement was an important step towards reaffirming Britain’s new role in these spaces: one concerned with listening, supporting and amplifying.

This is a role that TCEN member organisations from the UK have been trying to practice. “These activists face things that I’ve never faced. I grew up in a working-class Paisley family where things were very difficult, but I know when I enter this space that I’m privileged,” says Scott Cuthbertson of Scottish LGBT+ organisation Equality Network.

“I was speaking to an activist this morning who was worried that they’ll be arrested by their government because of their activism. I’ll go home to a relatively accepting country and they won’t they’ll be living in fear. But that’s why we’re here. Our role is not to lead on these issues, it is to provide a platform to support a diverse number of LGBT+ voices to advocate on their own behalf.”

Britain’s intention to amplify voices and work with activists is encouraging, particularly considering the challenges facing so many LGBT+ people within the Commonwealth. Pang says that in Malaysia, LGBT+ activists are oppressed by colonial laws that ban homosexual sex, but also sedition laws, which prevent them from speaking out against their government. “In Malaysia, LGBT+ activists have been called extremists so we are now on the same level as militant extremists,” he says. “I was arrested under the sedition charge for organising an art exhibition.”

For the first time in 60 years, Malaysia’s government has changed but this has not brought about the changes many had hoped for. “LGBT+ people feel like political pawns – and we’re being moved around the chessboard with no control,” he explains. “We are experiencing more silence and a serious lack of support from people who used to give us support.” Pang’s words display the truth that where LGBT+ people do not have legal equality, their position in society is increasingly fragile.

Sri Lanka, another nation which criminalises male and female homosexuality under colonial law, is also facing political instability. The country is still reeling from anti-Christian terrorist attacks which, on Easter Sunday, claimed the lives of almost 300 people. Last year Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court also ruled that the president had engaged in a constitutional coup.

While Sri Lanka’s political upheaval caused shock and upset, Rosanna Flamer-Caldera believes it galvanised people to take to the streets and protest. She wonders whether this LGBT+ visibility will last. “The LGBT+ community has gained some courage through coming out to protest,” she says. “But on the other hand, what will the government do once they come in to squash us? If things change, I wonder whether people would go back into the closet?”

Rosanna founded Equal Ground – a nonprofit LGBT+ organisation based in Sri Lanka – 15 years ago. She believes the recent political turmoil has shown that Sri Lankan culture is becoming more tolerant of LGBT+ people. “A couple of days after the coup, the president was heard making disparaging remarks about the sexual orientation of our prime minister,” she explains. “People in civil society, the media and politics came out, saying the LGBT+ community should not be denigrated like this.”

Rosanna is one of the most well-known female LGBT+ activists in the world. She is a co-founder of TCEN and is its current chair. As a woman working in LGBT+ activism, she knows better than most people about the forces of patriarchy working to suppress both LGBT+ people, women and, most strongly, LBT+ women.

In a country as patriarchal as Sri Lanka, this even affects the day-to-day running of her organisation. “I have two young women working at my organisation and their parents do not give them permission to come to any of our rallies,” she says. “Even working with our organisation is a problem for one of my girls, because her parents won’t let her work after 5pm. So she has asked to come to work at 7am because her father doesn’t allow her to be out after five.”

Even working with our organisation is a problem for one of my girls, because her parents won’t let her work after 5pm. She has asked to come to work at 7am because her father doesn’t allow her to be out after five

Rosanna says men have threatened her, pulled her out of her car and tried to beat her up in the past. But patriarchy is also rife within LGBT+ spaces and she has faced a lot of criticism, threats and harassment from gay men too. “I have to watch everything I say, everything I do as a woman. I have to strive harder, I have to shout louder. I have to struggle for every single thing I need. I have to constantly be aware that, because I’m a woman, there are people who are willing to do various things to me. That’s my life on a daily basis.”

Activists are trying to address this inequality. Amplifying women’s voices within the LGBT+ movement is vital because where inequality exists, women – who are less likely to have economic independence, equal legal rights and rights over their bodies – are increasingly marginalised. Queer women frequently experience targeted rape, through which abusers purport to “correct” a victim’s sexual orientation and those who do not conform to traditional notions of femininity may face particular vulnerability. The criminalisation of their sexuality means that they are often afraid to report these crimes or any discrimination in education, employment, health and housing.

Anna Mmolai-Chalmers from Legabibo – an LGBT+ organisation in Botswana – says lesbian, bisexual and trans women are often treated with hostility even within women’s rights spaces. “Anything that’s seen as different to the norm is seen as a threat. The women’s movement tends to be resistant towards the LGBT+ movement. It often sees our advocacy as a threat to theirs so there becomes a clash, even if many of the problems we face overlap.”

A new initiative funded by the British government is hoping to address issues affecting women and girls and LGBT+ people simultaneously. Announced last year, the Equality and Justice Alliance will work with activists around the world. This work is desperately needed. UK activist Natalie Armitage is a queer, mixed race woman working in global advocacy. She has seen first-hand the staggering inequalities that suppress LGBT+ women.

She laments that much of the contemporary women’s movement “100 per cent benefits” white feminism and largely ignores queer, non-white and working-class women. “Unfortunately, many women have not understood what they’re fighting against, or not really understood how patriarchy pans out,” she says. “Abortion rights, for example, are opposed by so many women I’ve met. This is a human rights issue and to deny women the right to make decisions over their bodies is human rights abuse.”

Yet even in places where LGBT+ people have greater legal equality, women are still marginalised. In Malta, for example, which has been deemed the best place to be LGBT+ in Europe for the last three years – easily beating the UK – abortion is not legal. Mark Harwood of Malta LGBTIQ Rights Movement also laments the lack of women in politics. “We perform really badly in terms of women in politics, I believe we’re ranked worse than Afghanistan. There’s still a lot of cultural resistance, particularly from the church, regarding the debate around legalising abortion too.”

Former UK diplomat Philippa Drew, now a trustee of Kaledoscope Trust and Human Dignity Trust, was motivated to engage in LGBT+ spaces after a lifetime of working in male-dominated fields. “In every job I had until I was in my forties, I was the first woman in the job,” she says. “I remember when I was working in the Home Office in the field of counterterrorism, we had to make a visit to the Essex police. My then boss said to his boss: ‘We can’t send Philippa to the police force because she’s a woman and they won’t accept her’. I ended up going and actually they didn’t have a problem with me. Somebody else assuming the police might have a problem with it is a barrier in itself.”

Fellow Kaleidoscope Trust trustee Phyll Opoku-Gyimah – co-founder and executive director of UK Black Pride – also welcomes work that addresses the barriers faced by LGBT+ women. “When you’re talking about women’s rights, we know we’re over represented in areas of crime which are committed against us and we’re over represented in low paid jobs,” she says. “If female genital mutilation is happening, how do we provide people with the tools to teach them that this is wrong and harmful? When we talk about health related matters for LGBT+ people, it may only seem to be solely focused around HIV. While this is absolutely important, some women can’t tend to their basic health needs in terms of menstruation or reproductive rights.”

Trans women are increasingly marginalised throughout the Commonwealth, with their basic health needs often unmet. June White of Haus of Khameleon – a trans-led LGBT+ organisation in Fiji – has been participating in grassroots activism with trans women in Fiji for the last 10 years. Fiji criminalises homosexual sex and the law does not recognise trans women. In May 2018, a young trans woman was brutally murdered in Suva on International Day of Trans Visibility.

June says trans women are disproportionately represented in the sex work community and targeted as criminals by the police. “We have police attacking trans girls on the street,” she says. But the trans community is increasingly aware of its legal rights. “Knowing your rights can scare the police away. If you know your rights, it’s a threat to them,” she explains.

For June the constant pressure of being a figurehead within the movement, with an expectation to create change, can take a toll. “We keep trying to change policies. But we this makes us targets on the front line. Sometimes we do things without thinking of our wellbeing or self-care,” she says.

Even as we talk in Mauritius, she’s worrying if everyone is safe back home. “I’m the primary contact for the girls. Sometimes it really affects the way I live. I’m not coping well, not eating well or sleeping well because of the work we do. It’s day in, day out. It’s become a lifestyle. I sometimes wish I hadn’t gone down this route, that I hadn’t given up this much of myself because now it’s impossible to take it back.”

In Jamaica, formerly labelled “the worst place on Earth to be gay”, J-Flag’s work to sensitise local communities and politicians to LGBT+ people seems to be slowly working. “It is still far from perfect. But there’s been a number of changes. More people are openly embracing LGBT+ people and are willing to say that they have friends or family who are LGBT+,” says Jaevion. “I think, as advocates and activists, we can’t pretend that our successes as a movement hinge on solely on legislative changes.”

Yet there is no denying that huge legal barriers remain, enabling further discrimination. “Just a couple of months ago, someone messaged me saying a friend of theirs had just been picked up by the police and threatened and asked for money because he was in a car with another man,” Jaevion explains. “They were not in a compromising position or anything, but this is how police intimidate gay men. Because of what the law says.”

One of the most fascinating things about the Commonwealth as a space is the vast array of religions which are practised across it. Anna Mmolai-Chalmers from Botswana says religion is one of the biggest roadblocks to her work. “The church is the biggest obstacle to a lot of things in Africa. It’s a threat to public morality, what I see morality as – being able to coexist and help one another,” she explains. “It’s often a gateway to corruption in Africa with the poor being taken advantage of and fake pastors taking money off people.”

In the northern region of Cameroon, which is mostly Muslim, the situation is more critical because we have lots of silent killings. If an Imam thinks that a child is gay, he might personally kill the child that evening

Hamlet, from Cameroon, says Cardinals have reframed past homophobic statements after he brought statements from the pope, which say that gay people should not be discriminated against, to their attention. Though Christianity is not the only religious force Cameroonian LGBT+ people face. “In the northern region of Cameroon, which is mostly Muslim, the situation is more critical because we have lots of silent killings,” Hamlet explains. “If an Imam thinks that a child is gay, he might personally kill the child that evening.”

In terms of Christianity, the most widely practised religion in most Commonwealth nations, there are significant worries about a new wave of fundamentalist evangelicalism, funded from abroad. Sensing the battle against LGBT+ equality is being lost in the west, well-funded evangelical groups from America have been spending vast amounts of money to build new movements and churches against LGBT+ equality in developing countries.

The election of president Donald Trump, who has brought in new rules which prevent US money being used to promote abortion or sex work oversees, has emboldened these forces. “It’s incredibly challenging,” Anna tells me. “You can’t even talk about those things while taking American money.”

“In Singapore, we have a vehemently homophobic and transphobic fundamentalist Christian lobby,” says Yangfa Leow. “They are evangelical, funded from America and very, very well resourced. They have disproportionate power and influence both financially and politically.”

Working for several UK-based international LGBT+ organisations, Philippa Drew has concerns the American funding of evangelical churches in poorer Commonwealth countries. “We only have to look at the change in the political environments in Brazil to see what’s happening. This country, which was one of the foremost countries for LGBT+ legislative rights, has gone backwards so quickly and hostility has risen. This prospect is very frightening for Africa too.”

As activists arrived on the first day in Mauritius, Philippa jokingly introduced herself as “the oldest lesbian in the room” during a round of introductions. People laughed, but this joke displayed that, within this group of activists, there are members who have dedicated their lives to this cause and there are others who, like her, are dedicating their later years to it.

When I ask Philippa where she gets the drive to spend her retirement years travelling round the world using her diplomatic experience to help expand LGBT+ rights, her answer is fascinating.

“Courage is something I think about a lot, because I meet a lot of incredibly courageous people. There’s physical courage, and there’s the courage to speak out when everybody disagrees with you. And so I do reflect on that I ask myself: ‘If I were a Ugandan lesbian, would I be as prominent as some of my colleagues are? I’m not sure,” she explains. “Having been in the closet for quite a long time, I wasn’t the first to come out by any means – I was scared to be out. There’s admittedly a feeling of guilt there.”

Nowadays, Phillipa feels settled in her identity as an out lesbian. She seems particularly comfortable speaking with fellow activists, who she regards as “like a family”. But her own struggles in the UK – such as being initially recommended against security clearance while working in the Home Office for being a lesbian – make her mindful of how quickly things can change. “The price of liberty is eternal vigilance. We should never be complacent, not about any human rights anywhere.”

Rosanna has been leading her fight for decriminalisation in Sri Lanka for decades, but says she has come to terms with the fact that she may never see it. “When I look back on my life today, I may not have reached reached my goal of decriminalisation. But the fact that I have dedicated my life to making sure the LGBT+ voices are heard, that’s enough,” she says. “I can go to my maker knowing that I’ve done the best I could on this issue.”

Anna has been fighting for the human rights of women and LGBT+ people in Botswana for decades. She is encouraged that there are so many young people like Melusi Simelane – a young man who recently organised the first Pride festival in Eswatini, the southern African nation formerly known as Swaziland – joining the movement within the Commonwealth. “That really gives me hope that the movement is going to grow to new heights. Giving young people a chance to lead and take on advocacy is something I’m really passionate about,” she says. “That’s something I see in Botswana as well and it’s a change. In the past older LGBT+ people were in charge, but now young people are taking on roles in the movement.”

The idea is to put forward stories about our lives, so that they provide a counter narrative to what the government is saying about us

Yangfa is also heartened by the younger generation. “Internet usage rates among queer youth in Singapore are really high. Everyone’s connected,” he says. “We’ve seen a lot of mobilisation of this space in the past 10 years by the community.”

As a network, these Commonwealth activists succeed in bringing together young and old identities, just like they represent the spectrum of identities which make up the LGBT+ acronym. Optimism is a thread that brings them together and each person is a storyteller.

Pang has even created a website in Malaysia for LGBT+ people to tell their stories. “The idea is to put forward stories about our lives, so that they provide a counter narrative to what the government is saying about us,” he says “It includes experiences of discrimination that we have faced, as well as our abilities and our attempts to overcome this, which we should celebrate as well.”

The idea of storytelling as activism, and of telling stories with people, not for them, runs to the heart of the UK’s new role within Commonwealth LGBT+ spaces. It is also fitting because the UK has challenges of its own. With transphobia and hate crime on the rise, the UK has fallen to 8th place on the Rainbow List – an annual list of the best places to be LGBT+ in Europe compiled by the International Lesbian and Gay Association. There are also concerns for how the UK will be able to use its influence to push for LGBT+ rights expansions post-Brexit.

Thankfully, each activist from the UK that I meet has a powerful story to tell. Paul Dillane was raised on a council estate in Swansea and got himself a place to study law by studying his A-levels at night school. Natalie Armitage brings her experience as a bisexual mixed race woman to her new role with UK Black Pride. Scott Cuthbertson, who has campaigned for nearly two decades to eliminate Scotland’s time ban on gay men donating blood, is resolved to bring the same drive and tenacity in the fight against rising transphobia.

As I prepare to leave Mauritius, my conversation with Phyll Opoku-Gyimah sticks with me.

As a black British lesbian raised in a time when she had to hide as National Front rallies marched through her neighbourhood in Hertfordshire, Phyll has her own relationship with race, sexuality and colonialism that has informed her experience of Britain and the world. She knows first-hand that Britain’s role within this space must be a supportive one that puts intersectionality – an understanding of interlocking forms of oppression – at the top of the agenda.

“There’s more unity here in this conference, than there is in the UK,” she says. “It’s empowering, but it’s also heartbreaking. When you talk to activists from St Lucia, Jamaica and Sri Lanka, it makes the decision I made to reject an MBE feel right, because of toxic legacy of colonisation that means that these members navigate sodomy laws and buggery laws that are left in their countries.”

“I recognise that I’m a British black woman. Colonialism played a huge part in structuring what racism is, but my experience doesn’t compare to what they have to deal with. I’m very much African, but in this space I recognise my privilege.”

My week with LGBT+ activists from across the Commonwealth was certainly an opportunity for me to address my own privilege as a white British gay man. When I say this to Phyll, she reassures me: “There’s nothing wrong with having privilege, it’s what you do with it that’s important.”

The next time this group meet, it will be ahead of the next Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 2020 in Rwanda. Activists will hope to build on the success in London while navigating an entirely different, more challenging environment.

As the sun sets on my time in Mauritius, Rwandan activist Hassna Uwingabe is optimistic. “Our nation is recovering from trauma, but if we can recover from genocide, then what is stopping us from accepting our LGBT+ people?” she says. “That’s why it’s time for me to be open as a lesbian and contribute to our new Rwandan society.”

By telling their stories these activists are proving that, together, optimists really can change the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments