Le Mans 1969: The greatest race ever run – anywhere

With the event set to kick off this afternoon, Mick O’Hare revisits the rich history of France’s annual 24-hour motorsport extravaganza

When New Zealander Bruce McLaren’s Ford GT40 crossed the finish line a fraction of a second ahead of Briton Ken Miles’s sister car at the end of the 1966 Le Mans 24 Hour race, it was the closest finish in the event’s history. For two cars to be yards apart after 24 hours and 3,000 miles of racing was an extraordinary denouement. But the finish had been stage-managed.

To celebrate Ford’s first win at the famous race, its racing director Leo Beebe instructed his drivers to stage a dead-heat – he was imagining the headlines and photographs the following day after his team had finally defeated the previously all-conquering Ferraris. He was also hoping to impress his boss, Henry Ford II, who was watching on.

But the race organisers got wind of the plan and expressed disapproval, pointing out that McLaren’s car had started further down the grid than Miles’s and so had travelled further (the rules at Le Mans differ from Formula 1 races – the winner is the car that travels furthest in 24 hours). But before this became an issue, Miles, not wishing to be part of a rigged result, dropped back a few feet at the last second allowing McLaren to take outright victory.

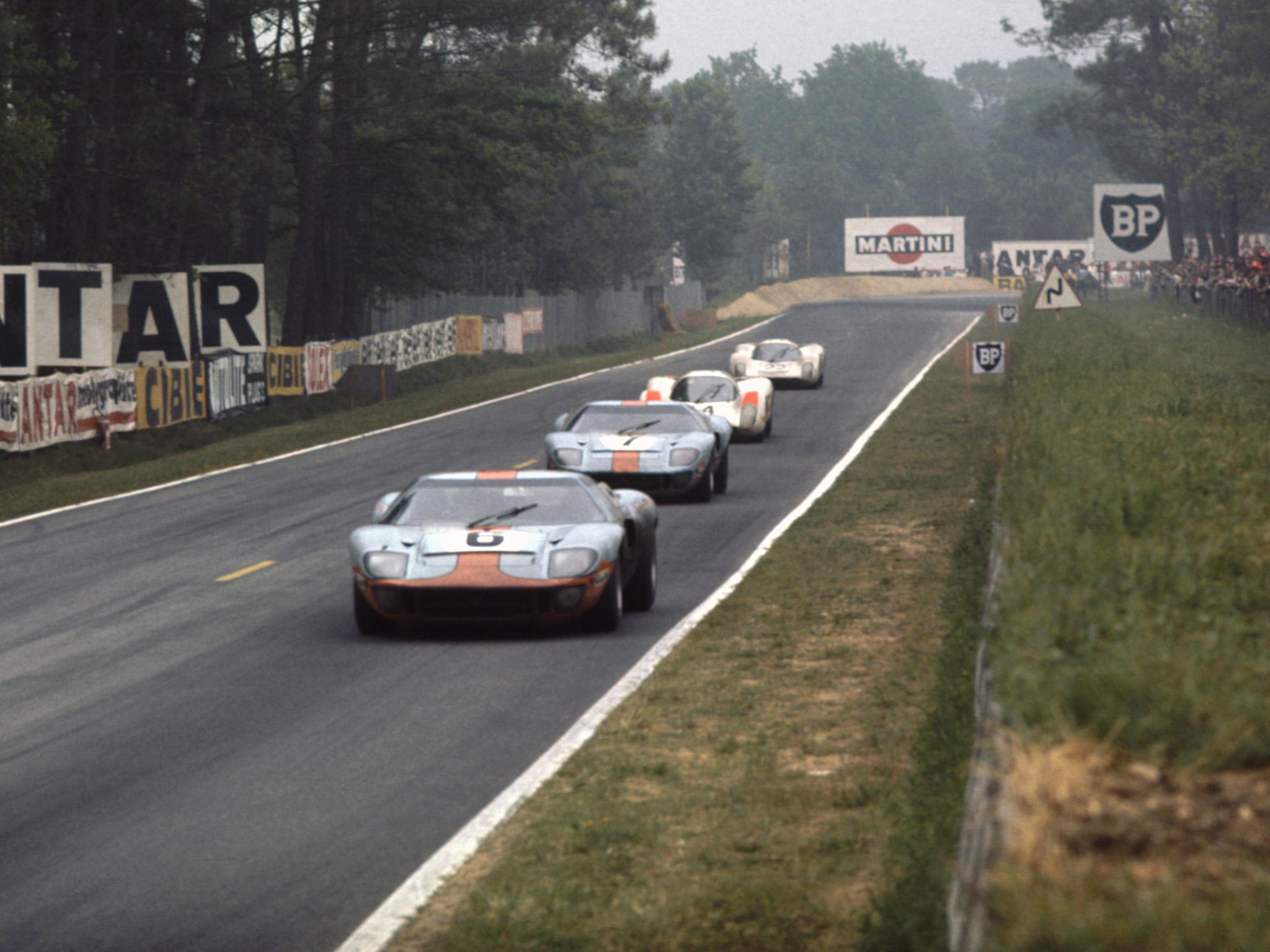

So despite it being – in the record books at least – the narrowest winning margin in the event’s 96-year history, the race that aficionados regard as the closest and, possibly, greatest took place three years later in 1969, exactly 50 years ago this week. This time the protagonists were Belgian Jacky Ickx and Hans Herrmann of Germany. Their duel over the final laps is still lauded today.

This year’s Le Mans begins at 3pm (local time) today. Cars will race non-stop through the night, finishing 24 hours later on Sunday afternoon. The race is steeped in motorsport history, a cliche of triumph and tragedy, colliding head-on each June in the Sarthe region of north-west France.

And it has its own idiosyncratic rules. While the cars are quick, reliability is more important. The car that is leading after 24 hours is declared the winner, but it must complete the lap it is on when the 24 hours are up, and at racing speed. In 2016 Toyota’s leading car broke down three minutes before 3pm, and couldn’t get to the line.

Le Mans is always run on a weekend near to the summer solstice to minimise night-time driving, and with slower cars from different categories also on the circuit alongside the potential victors in their high-speed prototypes, this leads to a distinctive and occasionally dangerous feature of the race – cars of different speeds occupying the same track at the same time. In 1969 the difference in speed on the fastest part of the circuit was as much as 100mph.

This means overtaking is an art, especially at night, and an error or a moment’s hesitation can be calamitous. Motorsport’s most catastrophic accident happened at Le Mans in 1955 when Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes struck the back of a slower rival and was launched into the crowd. The driver and 83 spectators died. Nowadays, fences and run-off areas thankfully ensure this cannot be repeated. And although only one driver sits in the car to race, each entry now has three drivers sharing stints to avoid drowsiness.

Ironically, in 1969, safety was at the forefront of Jacky Ickx’s mind. Traditionally at Le Mans, drivers started the race by running across the track to their cars and hitting the starting switch. Ickx considered this unsafe because drivers would head off on track without fastening their seatbelts to gain an advantage, so in 1969 he walked slowly to his car (almost being struck by a fast-starting competitor) and deliberately fastened his belts. Sadly, within minutes his point was made – John Woolfe fatally crashed his Porsche on the opening lap. His seatbelt was undone. The following year the running start was banned.

Ickx, aged 24, was Ford’s rising star – coincidentally his debut at Le Mans had been in the rigged 1966 race – while Porsche’s Hans Herrmann, 41, was a veteran of 17 seasons. Although they were to provide the spectacle over the final hours that would pass into motorsport folklore, in the early stages they were among the also-rans. As night fell, Herrmann was delayed for 29 minutes in the pits with suspension problems and Ickx was running far behind Herrmann’s Porsche team-mates – at one point a massive eight laps in arrears. Dawn broke and both were looking set for minor placings.

Years later Ickx would reflect on what happened that morning. “I wasn’t so sure that our rivals’ Porsches would stay the distance. Their 917 model was new and unreliable. I couldn’t account for my feeling, I just knew it was likely.” The 917 would become one of the most famous cars to race at Le Mans in future years but in 1969 it was still in early development – powerful, super-quick but still unstable at high speed as, tragically, John Woolfe had found to his cost. And Ickx was prescient.

In my racing days I often regarded a satisfying victory as one that required a duel between me and a worthy adversary. And you both have to be driving absolutely at your limit

With three hours left to run both leading Porsches suffered unexpected failures. All of a sudden Ickx (and co-driver Jackie Oliver) found himself ahead and Herrmann, driving an older 908 model Porsche alongside co-driver Gérard Larrousse, were into second and making up time rapidly on the Belgian, albeit still an entire lap down.

“The Porsche was quicker than my Ford,” explained Ickx. “And at one stage they had been four laps behind. I knew I would have to hold out for three hours, and we still needed to refuel three more times before the race ended while the Porsche only had to refuel twice.” Both teams knew that Ickx and Herrmann were the two best drivers and let them keep the wheel for the remaining time while their co-drivers were left to watch from the pits.

“In my racing days I often regarded a satisfying victory as one that required a duel between me and a worthy adversary,” says Ickx. “And you both have to be driving absolutely at your limit. That’s how it was with Hans and me.” Inexorably Herrmann closed in on Ickx until, entering the final hour and with all pitstops completed, he was a mere 10 seconds behind. Herrmann’s Porsche was faster, it was surely going to win.

But these were the days when the Le Mans circuit, a mix of public roads and specialist racetrack, had a long back straight known as the Mulsanne, and Ickx had a plan. The Mulsanne is now punctuated by chicanes to slow the cars to safe speeds, but in 1969 it was a full three-and-a-half-mile blast with cars reaching 230mph, faster than today’s Formula 1 cars.

As Herrmann finally overtook Ickx at the start of the Mulsanne, Ickx latched on to the slipstream of the Porsche in an attempt to make up for the deficiency in his Ford’s speed. “Television viewers saw this 30 times,” said Ickx. “I could hang on to Herrmann on the straight where normally my car should have lost about 150 yards each lap.” Then, on the tricky, winding section towards the finish line Ickx’s more nimble Ford could overtake the Porsche. It was cat and mouse.

“I had to keep close,” said Ickx. “If I lost concentration and missed the slipstream, he would be gone. It was like chess.” The two repeatedly overtook each other in a dramatic final hour, racing nose to tail. “Driving door-handle to door-handle for so long would have been impossible,” said Ickx, “if Hans had not been such a good driver and also my friend. If there had been animosity neither of us could have done it. I had full trust in him.”

It was like chess. If Hans had not been such a good driver and also my friend... If there had been animosity neither of us could have done it. I had full trust in him

But there was to be more drama. The Ford pit crew had miscalculated how many laps were remaining after Ickx’s last pitstop for fuel. With only a few seconds left on the clock, both cars crossed the finish line meaning another lap was required. Le Mans is a long circuit, more than eight miles. Even in that era of huge 5-litre-engined sports prototype cars it meant at least another three minutes of racing. But Ickx’s Ford had only ever managed 23 laps on a tank of fuel, it was now on its 24th.

However, he had a final card up his sleeve. He let Hermann pass him earlier than before on the Mulsanne, picking up the slipstream sooner than on previous laps to save on fuel. Diving out from behind Herrmann at the end of the straight he grabbed the lead, and on the winding run in to the finish kept the German behind. TV footage shows the cars sweeping towards the finish, Herrmann trying everything he knew. At the chequered flag Ickx took victory by 120 yards. It was truly breathtaking stuff for the crowd and the TV audience although Ickx himself has a slightly different take.

“Once or twice I purposely stayed behind him,” he says, “to lure Hans into believing victory was possible, but although the race was close and people ask me about it all the time, I knew that as long as I concentrated and as long as I had no mechanical damage I was going to win.”

He adds anticlimactically that: “My finest victory? Well it depends what a fine victory means. The final laps were hardly more than a formality. So I have often insisted that people are mistaken when they say it was my finest victory.”

Most people will disagree, including Hans Herrmann. Victory margins at the Le Mans 24 Hours are usually measured in multiples of laps, not tenths of seconds. Herrmann was disappointed at the time but now is happy to have been part of the greatest race in Le Mans history. “Despite the close racing, I too had figured out by the end that he was probably going to beat me,” he recalls. “But I tried all I could to defend the position on the last lap.”

Unfortunately for Herrmann, he had come up against probably the best of them all. Ickx would go on to become a Le Mans legend, winning the race six times. And, for the German, there was a happy ending. The next time out in 1970 he finally won the race at his 18th and final attempt giving Porsche their first ever victory, alongside his co-driver, Briton Richard Attwood.

He had promised his wife he would retire if he won, and was true to his word. Of 1969 he now recalls: “It was a fabulous, fabulous race in which I am proud to have played a part. And although I won the next year, that’s the race I recall more than any other.”

Ickx’s victory marked the end of an era for Ford who had won all the races from 1966 to 1969, Porsche and Matra would go onto dominate the early 1970s. Considering it took place over 24 hours and 3000 miles, with the final three hours enthralling spectators, some regard the 1969 Le Mans as the greatest motor race ever run anywhere. The introspective Ickx might disagree but there is little doubt it was sport of the highest quality.

There was one other Le Mans finish that was closer than 1969, probably more famous even than that race. In the eponymous motorsport movie Le Mans Michael Delaney played by Steve McQueen blocks rival Erich Stahler played by Siegfried Rauch on the final lap to allow his team-mate Larry Wilson played by Christopher Waite to take victory.

The margin – on the movie footage – appears to be about 0.98 of a second, or 15 yards. Ironically, the movie was filmed using real footage of the 1970 race won by Hans Herrmann. It wasn’t real, of course, although watch it today to get a sense of the sheer speed and breathtaking power of the cars of that era, skittering and sliding under braking. But make-believe cannot substitute for what really happened in 1969. Jacky Ickx and Hans Herrmann usurped fiction.

And in the intervening years Ickx has reassessed his win. “So if it wasn’t my finest victory, what was?” he asks himself. “Well I like a duel, and I had a duel that day. And in the absence of choosing any other race from my career, I think you can probably guess for yourself…”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks