India at 70: Horror of Partition sealed Nehru’s drive for a secular democracy after Independence

Anil Dharker's parents loved the multicultural and multi-religious city of Lahore – but that was before Partition. As the world’s biggest democracy celebrates 70 years, he looks back over a troubled and bloody past and is hopeful of a much brighter future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mine is a family of hoarders. Nothing worth any money, sadly, but perhaps full of precious memories. Yet what memories can old bank statements in their original envelopes, electricity bills and thank-you notes possibly hold? Age lends even scraps of paper an aura that means you can’t summarily discard them. So we carry the trunks with their mysterious contents from place to place and hope, one day, to find something of value in them.

The other day I did: a small, battered spectacle case. In it was a pair of “Gandhi” glasses with the familiar small, circular rims. What caught my attention, apart from my mother’s name handwritten inside the case, was the imprint on the box in gold lettering: Kirpa Ram & Sons, Manufacturing Opticians, Lahore”. You can’t get a more Hindu name than that and here it was, Mr Ram and sons, manufacturing eyeglasses for the gentry of Lahore, now in Pakistan, in what was then undivided India.

My parents were young. This was Dad’s first job. He had just returned from England after doing an MA at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies. (His thesis “Lord Macaulay’s Legislative Minutes” was published by Oxford University Press.)

So many ironies there – Lahore was beautiful then, my parents often told me. They were happy and comfortable and at home in a place so far away from their real home in Bombay. Lahore, at that time, was a multicultural, multi-religious city (Kirpa Ram & Sons!). Aurangzeb, the last great Mughal emperor, may have built the city’s grand Badshahi mosque but Lahore had also been the capital of a Sikh empire. It was, astonishingly, also the centre of the Hindu reformist sect, the Arya Samaj.

Another irony: my father’s book, lauded even by The Times Literary Supplement, is about Thomas Babington Macaulay. The politician was, in my father’s time, something of a hero. He is now reviled, particularly because of his efforts to reform Indian education. Most now remember him for this one sentence: “A single shelf of a good European library is worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia”.

Luckily, my parents left Lahore well before 15 August 1947, the day India became an independent nation. I say luckily because, to quote the opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. Independence didn’t come alone, it came with Partition in tow. British India had been one nation; independent India lost a chunk of itself, the part that became Pakistan.

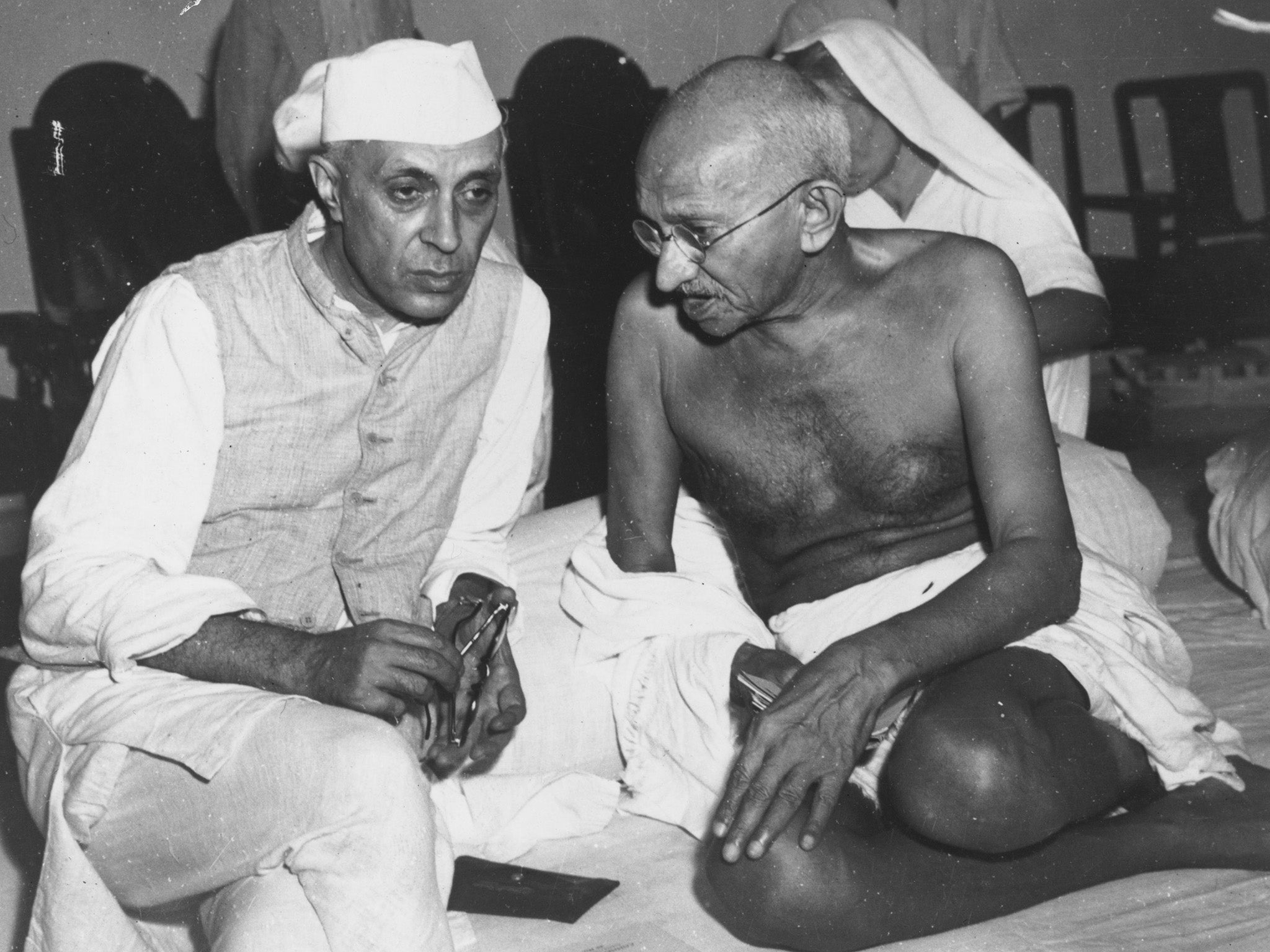

Why Partition happened is a long story. We would have to go back at least three decades before 1947 to see why Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the English-trained lawyer who drank Scotch, loved his bacon and married a Parsi (all taboos in Islam), felt that independent India would be a Hindu India, and Muslims would become second-class citizens there. The two-nation theory was never accepted by the Indian Congress party, and especially its great leaders, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru (incidentally, both English-trained lawyers), but the forces of history were too strong even for them. So Partition happened, bloody, brutal and long.

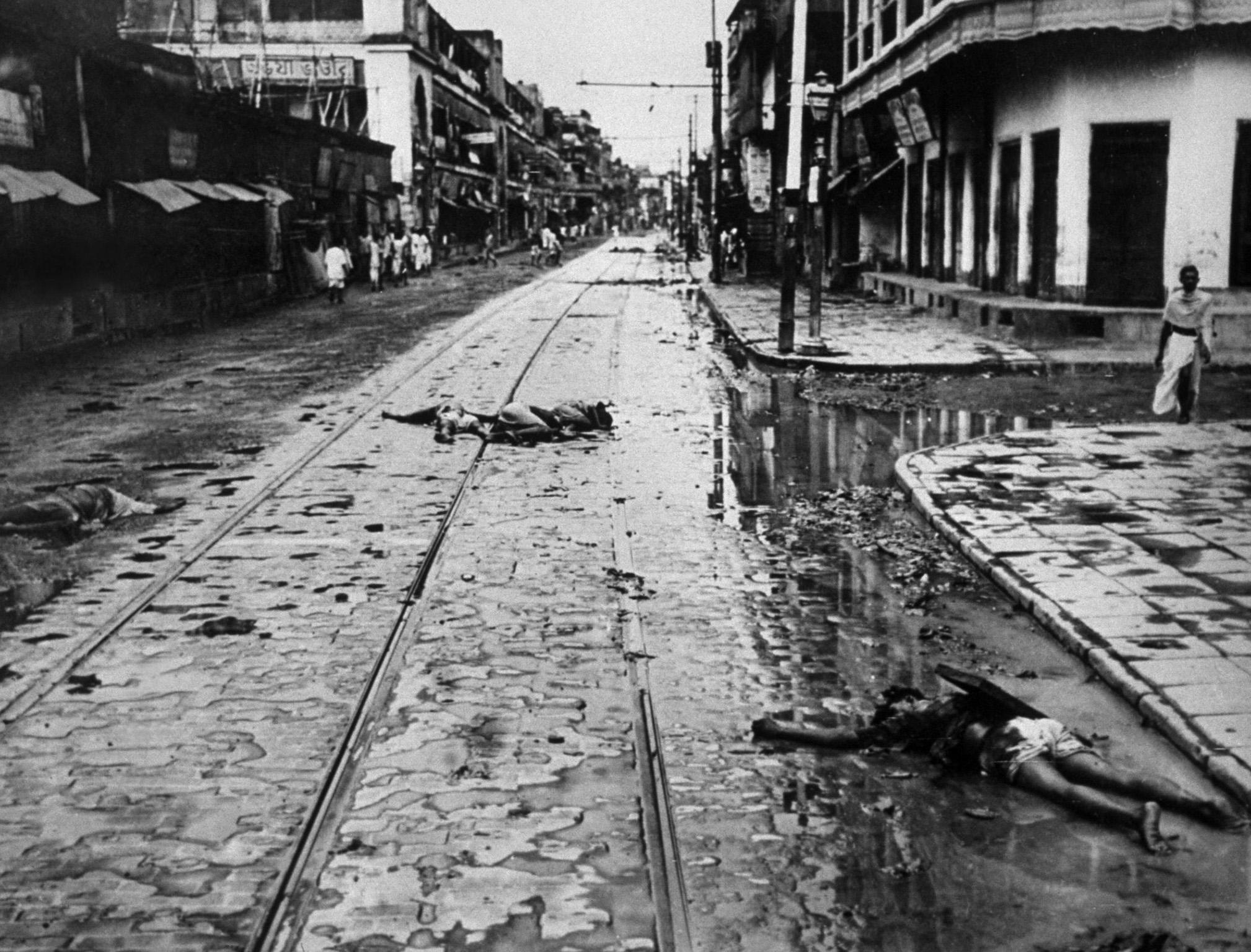

Actually sectarian violence began a full year before Independence. Bengal, with its mix of large Hindu and Muslim populations had seen many such clashes over the years. But the violence which began in 1946 was a deliberate design of Jinnah’s Muslim League to bolster the two-nation theory: the riots, it was felt, would send a message to the British that the two communities couldn’t live together in any kind of harmony. The Muslim League declared 16 August, 1946, “Direct Action Day” – also known as the day of the Great Calcutta Killings. The League, Jinnah said, wanted “either a divided India or a destroyed India”. Most of the victims of that day were Hindu. This in turn led to retaliation in Bihar, where most of the victims were Muslim, and the violence continued to Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. Gandhi walked more than a 100 miles in a seven-week period, through village after village in UP and near Delhi, in an effort to stop the violence.

The violent frenzy ensured that Jinnah had his way, and the British decided that India had to be divided into two countries, one of them (Pakistan) solely on the basis of religion. The frenzy was not just on the streets: the man summoned to do the job of partitioning the country was an English lawyer, Sir Cyril Radcliffe. Was he an India expert? No. He had never even been there! But this was considered a virtue, presumably on the premise that his would be an objective assessment, based purely on legal merit. He was given just five weeks to do the job.

WH Auden wrote Partition, a brilliant poem about it, which summed up the situation succinctly:

Unbiased at least he was when he arrived on his mission,

Having never set eyes on this land he was called to partition

Between two peoples fanatically at odds,

With their different diets and incompatible gods…

He got down to work, to the task of settling the fate

Of millions. The maps at his disposal were out of date

And the Census Returns almost certainly incorrect,

But there was no time to check them, no time to inspect…

But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided,

A continent for better or worse divided...

It certainly wasn’t for the better. In five weeks the Radcliffe Line was drawn through Bengal and Punjab, and as Radcliffe himself will have known before he began his task, it was to make no one happy. In fact, it made most Muslims, most Hindus and most Sikhs unhappy to the point of anger which erupted in fierce attacks and counterattacks. It wasn’t quite his fault, though. A Sir John Smith or a Lord Charlie Brown may have drawn slightly different lines, but the reactions would have been the same. How do you dismember a nation without pain? And without the anaesthetic of time, of laying the groundwork through long negotiations with the involved communities, how could there not be strife? Britain, once it decided to get out of India, was in an unseemly haste to do so. And haste, in this case, made terrible waste.

How many were killed in the violence in Bengal and Punjab? In the former, it was “only” a few thousand, because of Mahatma Gandhi. On 15 August 1947 the Indian flag was hoisted in Delhi and Nehru gave his memorable speech, “Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge... At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

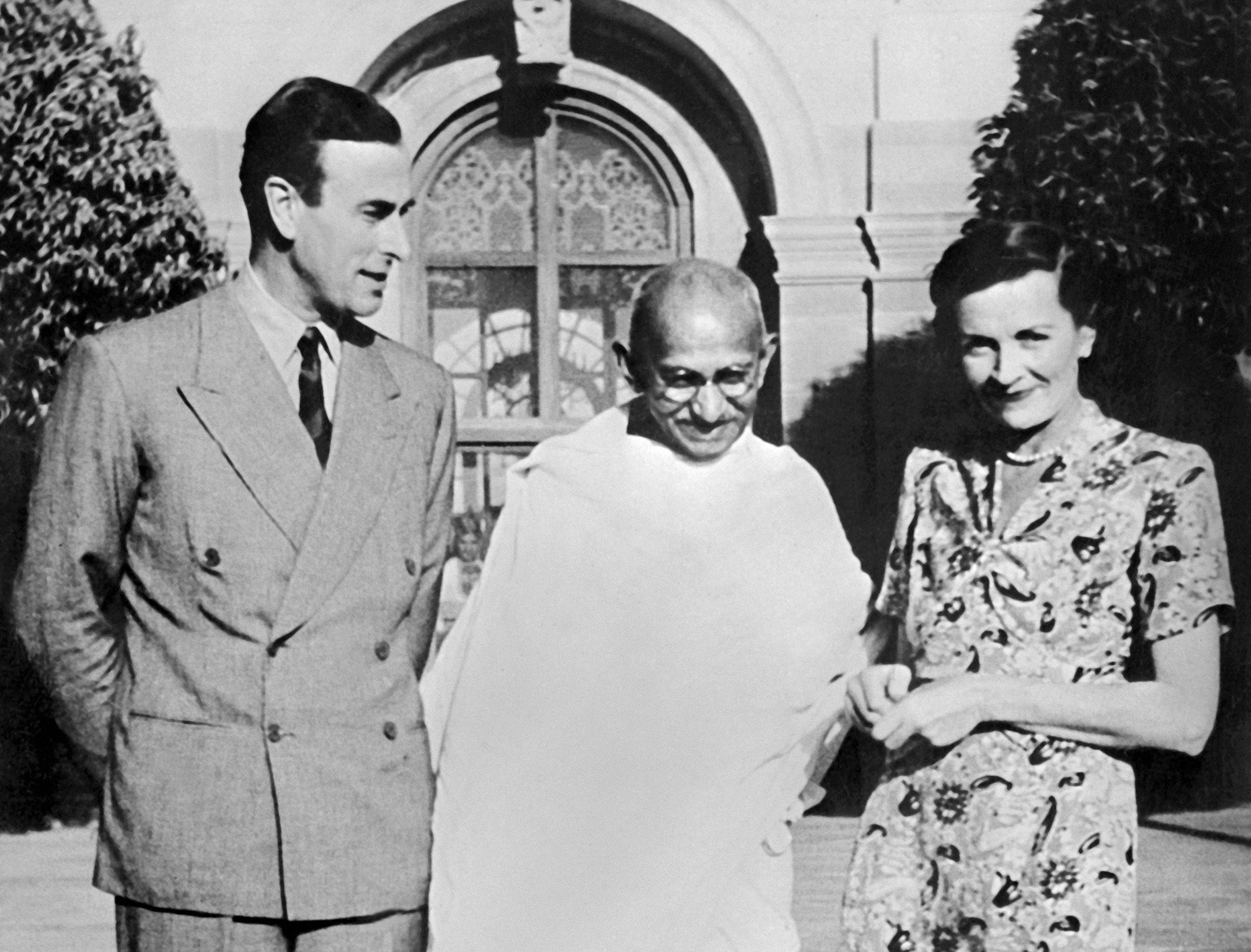

But Gandhi, the Father of the Nation as everyone called him, was nowhere near Delhi. He was in Calcutta, in a ramshackle house open on all sides in a Muslim area, on an indefinite fast which he had vowed to end only when the violence stopped. And, miraculously, it did on 15 August, and Hindus and Muslims came out together on the streets to celebrate freedom. Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, who had become the first Governor General of free India wrote: “In the Punjab we have 55,000 soldiers and large-scale rioting. In Bengal our forces consist of one man and there is no rioting.”

The rioting in Punjab, however, had gone out of control. As people fled their homes, from Pakistan to India and India to Pakistan, carrying what they could on their backs, bicycles or bullock-carts. One killing here led to a retaliation there, and so on and on. The virus of hate spread unchecked: estimates of people killed ranged from 500,000 to two million. With such massive displacement, there was just no way to arrive at accurate numbers. You could only say that there were far, far too many deaths. There was also unspeakable cruelty, with people who had been friendly neighbours turning into terrifying murderers. Gandhi and Nehru risked their lives in trying to stop the madness; Jinnah, it is said, hid in his home, too terrified to confront the rampaging mobs. But the violence had taken on a life of its own.

It resulted in the greatest mass migration in history: 10 to 12 million people were displaced; there were reports of convoys of 100,000 people walking in lines which stretched for as many as 10 miles. At the end of it, the two new and bloodied nations had on their hands 10 to 12 million refugees, penniless, homeless, jobless. It was no way to start a nation.

The wonder of it is that India has survived for these 70 years not just as a nation, but as a democratic, secular country. There are imperfections, of course (and a billion voices will be ready to tell you about them), but the foundations led by Gandhi and Nehru have remained firm. Nehru`s Independence eve speech, quoted earlier, ends, “All of us, to whatever religion we may belong, are equally the children of India with equal rights, privileges and obligations…”

It is a significant line and laid the principle which the new country would follow in dealing with minorities. Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel, the Congressman from Gujarat who became the deputy prime minister and home minister, were of the same view. In fact, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic on 30 January 1948 for his perceived favouritism towards Muslims. Patel, sadly, also didn’t live long after Independence and died of a heart attack in December 1950. Thus the entire burden of leading India fell on Nehru’s shoulders.

Nehru was Prime Minister from 15 August 1947 till his death on 27 May 1964 – almost 17 years. It wasn’t just the length of his premiership; it was the fact that these were the very first years of a new nation, and therefore vital in determining in which direction it would go that’s important. That India has remained a stable democracy, that it has maintained its secular nature, that free and fair elections are held at regular intervals, are all due to his towering personality.

Even as a young boy, I felt his magnetism. There was no television then (he would have been a star on TV), just the occasional radio broadcast. But Indian newspapers were always full of him. His sharp Kashmiri features made him extremely photogenic, and in most ways, he personified the word charismatic. I remember the whole extended family lining up the street when Nehru came to town – we hadn’t done this for anyone. As he passed us in an open car, he threw his trademark red rose in our direction. An aunt caught it, and I won’t be surprised if it’s still with her in a little box locked away carefully somewhere. The adulation for Nehru was universal.

Whatever Nehru’s failures – and they came to haunt him in his declining years – it is important to remember that today’s India could have been very different if it hadn’t been for him. The horrors of Partition were fresh in everyone’s mind in 1947; yet minorities, especially the Muslim minority, were all treated as equal citizens. Pakistan became a nation founded on religion; and look at Pakistan now. Around the time, or soon after India got its independence, many countries in Asia and Africa got theirs too: most of them have gone through years of military rule or dictatorships; and democracy, if it’s there at all, is fragile.

Nehru’s dominant personality could have made him a dictator but his belief in a democratic system was so strong that he wanted the first general election to happen as early as possible. He did not want any half-measures – no electoral college, no voting rights restricted to people of property, with the poor (and women, as was the case in Switzerland) excluded from exercising their franchise. Two years after Independence, the Election Commission was set up, and the first general election took place in 1952.

Ramchandra Guha, in his monumental history India After Gandhi, gives us an idea of the colossal nature of the exercise. The size of the electorate was 176 million, about 85 per cent of whom were illiterate (hence the need for party logos to identify candidates). “At stake,” Guha writes, “were 4,500 seats – about 500 for Parliament, the rest for the provincial assemblies. There were 224,000 polling booths constructed, and equipped with two million steel boxes… 56,000 presiding officers aided by 280,000 helpers; 224,000 policemen were put on duty.”

To further complicate matters, the polling booths were spread over an area of more than a million square miles. Guha wrote: “In the case of remote hill villages, bridges had to be specially constructed across rivers; in the case of small islands in the Indian Ocean, naval vessels were used to take the [electoral] rolls to the booths.” Apparently, many village women had their names struck off the rolls because they were too shy to give their own names but gave them as “wife of. . .”!

Elections since then have, of course, become bigger with the country’s burgeoning population: at the last general elections in 2014, the size of the electorate was 814 million, four and a half times that of the first election. But it was the 1952 election that set the tone – and except for the two years of the Emergency, declared by Indira Gandhi from 1975 to 1977 – India has remained a country where a citizen, however poor, has a vote which carries the same weight as that of India’s richest industrialist.

Seventy years on, that’s something to be proud of. Even more is the fact that the idea of India as one country has survived, in spite of the country’s huge diversity and population, which makes it akin to a continent. Numbers confirm this amazing story: India’s population is now over 1.2 billion, spread over 29 states and seven union territories. There are 22 official languages and very many more dialects. Each state has its own language, culture and cuisine. At the time of Independence, when Vallabhbhai Patel, Nehru’s deputy, began the massive exercise of making the country into one unit, India was made up of more than 500 princely states. Now none exist.

Not even the most flag-waving Indian however, will claim that everything is perfect. The caste system refuses to die out; Dalits (the term used for untouchables) still face upper-caste persecution; they and minorities (especially Muslims) remain equal citizens only on paper; conservative and orthodox men still resist women’s fight for equality; the criminal justice system and the police still favour the affluent; reactionary religious elements still create tensions and face the future backwards.

Yet, even though things move forward slowly, they do move. India has just elected a Dalit president in by Ram Nath Kovind. Women are forcing their way into positions of influence. The media is free and fierce in righting injustice. Most importantly, young men and women, with the impatience of youth, are moving the country into modernity. For them, to paraphrase Nehru, technology is the temple of today and of tomorrow.

Anil Dharker is a columnist and writer. He is also the founder and director of the Mumbai International Literary Festival

For more on our Partition series click here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments