How to tackle the knife crime epidemic: 'It's really quite simple – we need to change the whole system'

More people than ever are carrying knives, and it’s not just a gang thing. So how do we go about solving such a destructive habit? Joe Lyness and Sebastian Powell hear the views of, among others, a mother who lost her teenage son to a stabbing and an armed robber whose life has been turned around

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

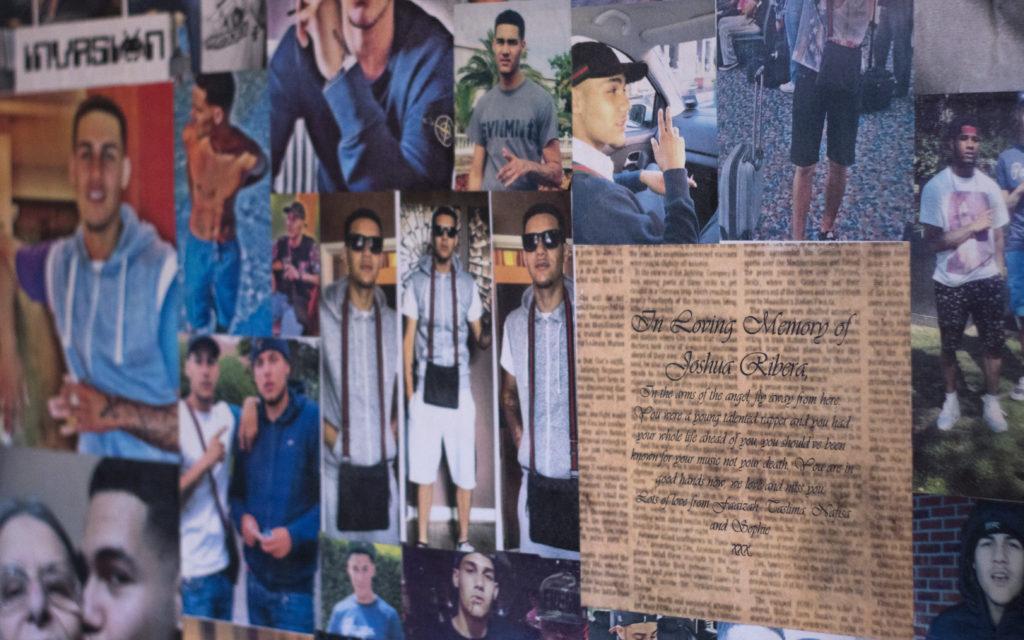

Your support makes all the difference.In his song “One Love” Joshua Ribera, known as Depzman, sings: “Gotta make my mum proud and my dad too. Gotta stay on the straight and narrow because one day I’m gonna be a dad too.”

But just 57 days after “One Love” was released his dream was over. Stabbed through the heart by a teenager in a row over a girl, Ribera’s life was abruptly cut short. The brutal attack also spelled the end of normal life for his attacker, Armani Mitchell.

Ribera was one of over 200 people in 2013 lost to knife crime. In the five years that have passed since his death more than 1,000 other victims in the UK have been killed by a knife, an epidemic that continues to rise.

“I never thought it would happen to me. I knew knife crime was an issue, but you never expect it to happen to someone you know. You can’t even begin to explain how it feels until it hits you,” his mother Alison Cope remembers.

Like most mothers Cope could never have imagined her son’s death, “If you speak to any parent they will bore you telling you how advanced their children are, how amazing their son or daughter is. I’m still doing that about Josh. I’m still telling people my son was wonderful and about how much I loved him. That’s what enables me to still be his mum, even when he’s not here.”

On the night of 20 September 2013 Joshua was attending a fundraising event in Birmingham for his friend, and fellow MC, Kyle Sheehan, who had been stabbed and killed a year previously at the age of 16. After performing at the event Ribera was confronted by Mitchell, the man who later that evening killed him, with a single stab wound that directly punctured Ribera’s heart. He cut short a young life on the brink of success and happiness.

Known to many by his stage name Depzman, Ribera was a prominent name in the UK Grime scene, tipped by many to become a star. Aged just 18 he had gained notoriety as an MC with viral releases on YouTube channels SBTV and P110 Media and had just release his debut EP, 2 Real.

With a smile, Cope recalls her son’s obsession with music being clear from a young age, regularly practicing his lyrics in his room from the age of eight. Having this focus and outlet is what Cope believes kept Ribera out of trouble, and lead to his rapid rise in popularity as one of the UK’s most admired MCs.

Ribera’s popularity continued to flourish, even after his death. Cope has been inundated with fan mail, and Ribera’s room now stands as a memorial to everything he once was. Young people from around the country have sent in their own drawings and collages of Ribera, not only to share their condolences, but to express their gratitude and admiration for both Ribera and Cope. Comment sections beneath Ribera’s YouTube videos are littered with tributes, and speculation to what he could have gone on to achieve, had his life not been cut short.

“As a parent he achieved everything I wanted. He stayed out of trouble, achieved his dream. He was going to be Depzman. He was going to conquer the world.”

Despite such a harrowing experience Cope’s strength when recalling the event is phenomenal, “Josh lost his life, but he wasn’t the only victim. The moment Josh died, we have another 18-year-old boy who is a murderer. The police will arrive at his mother’s door to say that your son is a murderer. Your nephew, son, grandson is a murderer. The police, the trial, every anniversary I face, they face, every press interview I face, they face. It will pass on through the generations. When a child dies through murder, you can never get over it, you can never move on.”

Cope is not alone. The number of people in the UK losing loved ones to a knife is continuing to grow. The number of police-recorded offences involving a knife or sharp instrument is at its highest in seven years, after a downward trend since 2011, now 38 out of 44 police forces are reporting a rise. This problem is overwhelmingly a young male issue: 95 per cent of those caught with a knife are male, over half of whom are 25 or younger. So what is the influence behind an epidemic that has seen a 30 per cent increase in knife-related offences since Joshua’s death, and what is driving so many young people to turn to deadly weapons?

For John Costi knife crime has always been a reality. Arrested in 2004 for a series of armed robberies, he grew up surrounded by violent crime. “Back then carrying a knife was normality for me. Whenever you went out you made sure you had your house keys, your phone, your borer – which was what we used to call a shank – because when I was growing up it was just everywhere. Almost everyone I know has been stabbed or been to jail.”

Born in north London, Costi became involved in crime at a young age and for him carrying a weapon was part of this. “I started selling drugs at 12 and carrying a knife and things just came with that. It was what I know now to be toxic masculinity but it was just this idea of being tough.”

“If you got caught slippin’ you had to be able to back beef or whatever you’d call it. This gangsterism is a mental illness, you actually believe that you are a bad boy.”

Costi believes that his reasons for carrying a knife are linked to isolation while growing up.

“That alienation consumes you, it means you want to be a bad boy, you want to be the very worst you can be. It’s often to do with traumas you have been through and shit you had to go through while growing up which leads you to believe the world owes you something. When you believe the world owes you something it means you want to take from it. It’s the same with turf wars, if you ain’t got shit you’re going to protect that shit little bit you do have, even if that ultimately means extreme violence. If you have nothing you have to fight over crumbs.”

Craig Pinkney, a criminologist and lecturer who specialises in working with at-risk young people, has analysed young people’s relationships with weapons as both a practitioner and an academic.

“There are some young people who carry knives because they like to hurt people, there are some young people who carry knives because their friends do and it’s seen to be a cool thing to do,” he says.

Stereotypically, knife crime is seen as a symptom of gang culture and gang-related violence. Yet recent statistics show that gangs are no longer the primary source of knife carriers. It is now estimated by the Metropolitan Police that 75 per cent of those caught with a knife in London have no connection to gangs.

So why are a greater number of people carrying knives?

One answer could lie in changes in funding to youth services. Without the vital support offered by youth clubs, many young people now find themselves exposed to dangerous environments. A study by the trade union Unison found that an estimated £387m has been cut from youth service by local authorities from 2010 to 2016, with the average council in London having its youth service budget cut by nearly £1m per year – an average of 36 per cent.

Pinkney argues that it is inevitable that young people will equip themselves with weapons as long as they continue to bear witness to traumatic incidents involving knives. He goes on: “There is a category of people who carry knives because they’re scared. They’re scared to go to school or to catch the bus, so they want to protect themselves. If I was in a position where I felt scared then of course I’d arm myself. And that’s me being realistic.

“Youth workers just aren’t fit for purpose and the youth centres aren’t there anymore. I totally understand why a young person would carry a knife, I completely understand it.”

Costi also recognises this problem. “There are so many factors as to why young people are hurting each other and why violence is so prevalent,” he says. “There’s not one answer for it because otherwise we would have dealt with it by now... how do we break the chain?”

Statistics from the ONS show that the total number of selected offences involving a knife or sharp instrument have increased across all forms of violent conduct since Ribera’s death in 2013.

While working with young people Pinkney has seen the issues presented by a rapidly shrinking budget for youth services. “Since 2009-10 knife crime has been bound to increase after funding cuts began to happen across the country. Youth centres are being shut left right and centre, this means young people are spending more time hanging around shops and on estates and being noisy at night time. There is a direct link between boredom and antisocial behaviour.”

It is apparent that knife crime isn’t simply a case of young people wanting to hurt each other. It is much deeper than that. Christian Foley teaches across a number of London schools and pupil referral units and through his close work with young people in deprived areas recognises how becoming involved in knife crime can be as a result of socio-economic pressures. “People that carry knives are a product of their environments. You only carry a knife if you feel like your life is in danger. You only feel that your life is in danger if you are in an area where knives are present. You’re only in those dangerous areas if you are generally in poverty or somewhere with a high crime rate and low income, perhaps a broken home.”

Clearly knife crime prevention needs to be explored, and the reasons as to why young people are deciding to carry deadly weapons also needs addressing. However, what happens to the families of victims? The possession of a knife can tear a family apart. The ramifications of a violent outburst can be cataclysmic. In a split second, a family’s life can be changed forever, and events such as Ribera’s murder raise an important question. What action needs to be taken against those who decide to carry a knife?

While it appears that there is no clear and simple solution to the issue of knife crime, the judicial system has a key role in deterring people from becoming involved, and subsequently punishing those who do. Policing, surveillance and sentencing remain pivotal in combating the knife epidemic, but with falling police numbers and what many see as soft court punishments, is enough being done by the authorities to help quell such a problem?

Ministry of Justice figures released earlier this year show that currently the amount of knife crime offenders being sentenced to immediate custody is increasing, and so is the length of their sentence. Last year 36 per cent of those arrested for knife and offensive weapon offences were given an immediate custodial sentence, compared to 20 per cent in 2008. The average sentence is also on the increase and is now 7½ months – a 2.2-month increase over the past 10 years. Despite these increases many still believe that sentencing needs more clarity, and should be firmer to deter people from picking up offensive weapons.

Peter Kirkham, a former detective chief inspector in the Metropolitan Police, who now acts as an anti-knife crime campaigner, believes that this change doesn’t act as a deterrent to those thinking about picking up a knife. “No kid carrying a knife is going to be worried about a few percentage points over 10 years,” he says. “No kid that’s thinking about carrying a knife is gonna be more deterred by an average sentence of 7½ months over 4 months, it’s going to have no effect.”

Kirkham believes that for sentencing to work effectively in the fight against knife crime, people must be aware of the punishment.

“For a start the average person on the street who is carrying a knife isn’t going to have a rolled-up copy of The Guardian in their back pocket. It’s got to be dramatic enough for people to start talking about it on social media, YouTube and the ways in which young people get their news.

“They’re not going to see a Guardian article talking about a fairly marginal increase in knife crime sentencing.”

This kind of deterrent sentencing has been seen most recently in relation to the increase in acid attacks in 2017. “The guy who threw acid in the club, it was a high-profile case because he was a celeb, he got 22 years. I think that that is a deterrent sentence. The guy that’s been convicted for the moped attacks was a juvenile when he committed the offences, juveniles are used to no custodial sentences. But he was given 10 years. Young people look at that sentence and go, f**k – that’s not really what we want.”

Cope has experienced the horrors of knife crime through the loss of a loved one, but has also seen first hand the process of arrest and sentencing that follows the act of extreme violence.

She echoes Kirkham’s view that those responsible for knife crime should be held accountable for their actions.

“We can’t have people walking around with a knife and say, oh don’t worry about it. If they’re aware of the consequences but still go on to choose to carry a knife, then they have to live with the consequences. We need clarity, if you carry a knife, this is what happens. You can’t allow people to be walking around with dangerous weapons and getting away with it.”

Through his work as a criminology lecturer Pinkney speculates that even though sentencing is a necessity, it perhaps isn’t the best long-term answer. “Sentencing should be seen as one part of the solution. But our prison population is almost 90,000, so it obviously isn’t having an impact on individuals carrying weapons.”

Currently, almost 30 per cent of those convicted of a crime go on to reoffend, and this number increases when looking at youth offenders, with 42 per cent of 15-17-year-olds going on to commit another offence. These shocking statistics become even worse when focusing on the initial sentence. In 2016, out of all juvenile offenders sentenced to a custodial sentence, 68.1 per cent went on to reoffend, and on average reoffend five times or more.

Reflecting on his experience with the criminal justice system Costi agrees with Pinkney that although sentencing is one part of the issue, it does nothing to deal with the cause. “This is a problem across the whole system though. They think punishment helps but it just f**ks you up more, it just alienates you more,” he says, shaking his head.

“If you go prison you are made to feel like nothing, like nobody wants you, and that’s valid in some sense. Don’t get me wrong, if you do bad things you need to be punished, and dangerous people need to be segregated from society, but where do we need to go from there? It’s the whole idea of locking them up and throwing away the key. When they come out are they just meant to be cold hard killers? How do you address the archaeology of their offending, how do you go beneath it?”

Despite Costi’s troubled background he is a prime example of how this chain of violence and reoffending can be broken. In his case he was saved by his love for art.

“I’ve always liked art, well, I’ve always loved it really,” he says. “It was the only language I could understand, whether it was graffiti or even rap.”

While in prison, Costi attended art therapy sessions and, after being asked by the warden at Feltham young offenders prison to paint a mural, was moved down to a D-category prison where he began running art sessions for adults with Down Syndrome.

Costi explains how this sense of responsibility was a key part in preventing him from reoffending. “This was such an important part of what I wouldn’t even call my rehabilitation, because there was no ‘re’ about it. To see my art have such an instant and profound effect on the people I was doing it with and how it could change their mood so quickly... it gave me so much fulfilment to use my art as a social tool.”

At the age of 21 Costi was given day release, allowing him to attend Kensington and Chelsea College one day a week to study art. “I was going from this prison in south London to do a course in the most bougie part of London, surrounded by the bougiest people, which was a bit of a head f**k,” he laughs.

While still in prison he completed his application to study fine art at Central Saint Martins, and began studying there a few months after he was released.

Costi stresses how important the time is directly after being released in stopping reoffending.

“Luckily when I came out I still had some time on my course which gave me some purpose. That’s the problem with trying to change yourself, the people you were around you will always expect you to adhere to old habits. Friends try and give you drugs to sell because they think they are doing you a favour, which is understandable when you’ve come from those circumstances, but that’s why people reoffend... I’ve seen people do it in hours.”

He went on to graduate from university with a first-class degree and has received critical acclaim for his piece “My Darling Johnny”. He now focuses his time on working with at-risk young people through the charity Art Against Knives.

“I work with some of the most at-risk young people in London, there’s a lack of role models for these kids when everyone’s fighting over crumbs. They see that their elders have got money and got cars, they’ve got girls, they’ve got everything a teenager wants... they need to be shown there’s a different path. Unless you did this shit yourself they’re not going to listen to you. The best youth workers you’ll meet were probably going to be the best gangsters you’ll meet as well. You get a lot of people in this sector and they’ve just read it in a book, and the young people just don’t listen to them.”

Having a sense of validity to young people is something that Cope has also found helps her work preventing knife crime. “It is clear that Josh’s profile has an influence, when I go into schools they know who I am. That’s why I get such a response from the young people,” she says proudly.

Almost five years after Ribera’s death Cope is now a central campaigner in the UK’s fight against knife crime, dedicating her time to working with social services and the police in Birmingham to help prevent young people from becoming involved in violent crime.

Cope is adamant she never intentionally became involved in campaigning, but instead just fell into her now crucial role. “I never woke up and thought I want to make a difference because knives are killing our young people. I never thought like that. It just happened, Josh died in the morning and in about four or five hours I had a house full of emotional grieving youngsters”, she says.

Even though becoming a campaigner was never Cope’s intention, she now recognises the influence she has on young people, and admits that her career is now set in stone. “My life is this now. I get such a response from the young people that I can’t give it up. It drives me, and the reaction of the young people gives me such a sense of achievement. Until the authorities realise the way to help these young people is to pick them up, and not shout them down, I’ll carry on.”

Both Cope and Costi have used their own experiences to create a relationship with young people that allows them to offer guidance and help them to avoid becoming involved in violent crime.

However, the issue of knife crime still remains at an epidemic status. It is clear that the support provided by individuals with involvement of knife crime is not available across the country, and that more needs to be done on behalf of the government to tackle the problem.

Sarah Jones, MP for Croydon Central and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on knife crime, states how, even though public authorities are beginning to turn their heads to a new approach, the tactic employed by the current governing body isn’t working.

“We need to convince [the government] that spending money has to be part of the solution because in the long term you can arrest a load more people and lock them up but that’s not going to make the problem go away.”

For Pinkney this direct link can be seen as a driving factor in the increase in knife crime and he believes that in order to solve this knife crime epidemic, we must completely rethink our current system, and push to one in which education is at the core.

When asked about how the epidemic of knife crime faced by the UK could be solved, Pinkney answers confidently. “It’s really quite simple – we need to change the whole system.

“The system we have been following has always been the same, it’s a criminal justice approach. We wait for young people to commit crime or to do something wrong, then we put intervention in place. It’s too late. We need to take a public health approach.”

Jones is also an advocate for a reformed approach. “The approach of the government to date has been very much on the policing side and the judicial side. That approach clearly hasn’t worked.”

Like Pinkney, Jones believes that we must move towards looking at knife crime as a public health issue in order to stop the epidemic.

“There’s various elements to the public health approach, and basically it all comes down to trying to stop people carrying knives in the first place. For this to happen you need to treat the problem itself, and that means things like intensive youth work and proper interventions with young people. It also means immunising the community against it happening again in the future, which is about education and mental health. We need to try and change social norms.”

Pinkney’s confidence in this method of dealing with knife crime seems unwavering, and he points to places such as Glasgow and Chicago for precedent. A report published by the United Nations in 2005 revealed that Glasgow was the UK’s most dangerous city; since then the Scottish city has utilised a reformed public health approach, and violent crime has decreased dramatically.

Prior to the reform, Scotland had the second highest murder rate in western Europe, with Scots three times more likely to be murdered than people in England and Wales. Police in Scotland have since started working with those involved in health, education and social work sectors to address the problem, and since then, the recorded number of incidents that involve an offensive weapon has fallen 69 per cent in a decade.

Pinkney speaks passionately about the approach, but admits that it will be an expensive method to enforce. “We need to try a different approach, and unfortunately, that’s going to cost a lot of money. The criminal justice system is being overflowed, the prison population is almost 90,000 now, which has more than doubled in 30 years. Surely this means that we need to try something else.”

When asked about why, with all the evidence pointing in its favour, the government isn’t pursuing a public health approach Jones explained: “One of the issues is that the government doesn’t have the will to invest, and these things cost money.

“What we are seeing in London is children being excluded from school because they often have undiagnosed special needs or behavioural issues that go unchallenged until they’re at crisis point. There aren’t enough resources and special needs provisions any more, class sizes are bigger and there’s just one teacher dealing with everyone. This means more people are being excluded and going down a path of going to pupil referral units and ending up in trouble.

“The solution to that is investment in education, and the government isn’t willing to do that at the moment. Since I started talking about it in parliament the response from government has changed over the months. It was that they were looking at increased sentences and stopping the sale of knives and the judicial system, focusing on the punishment and policing end. They are now saying that we welcome the work the all-party group is doing, and recognise this is about more than policing and that it has got to be about prevention.”

The benefits of this approach are also being analysed on ground level, by people like Foley, who work with at risk young people every day. “Taking knives off the streets doesn’t work because they’re so easy to access, you can get them in the kitchen, so you have to change the psychology of it so people don’t want to carry knives. The only way they won’t want to do that is if they have a better option and they’re only going to get better options through education. Even if you are just helping a kid get a GCSE you are lessening their chances of getting involved in knife crime.

“The solution is not using one solution; if something isn’t used in conjunction with others then it will fail as everyone has before. It needs to be a multifaceted strategy that involves harnessing, prisons, schools, youth centres, outreach workers, the whole system.”

Jones is optimistic that there will be a change in the system, “We are now beginning to see pots of money – and it’s nowhere near enough, but we are beginning to get that shift. I think we need to carry on making that case so that those in government feel the pressure and see that there are a lot of people who want this change, otherwise they won’t act. We need to convince them that spending money has to be part of the solution.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments