Why do we assume that someone being paid to do nothing should consider themselves fortunate?

Economists say that maximum pay for minimum work makes people happy. Anyone who’s ever had a dead end job knows that’s not true. Anthropologist David Graeber explains why

Why do we assume that someone being paid to do nothing should consider himself fortunate? What is the basis of that theory of human nature from which this follows? The obvious place to look is at economic theory, which has turned this kind of thought into a science. According to classical economic theory, homo economicus, or “economic man” – that is, the model human being that lies behind every prediction made by the discipline – is assumed to be motivated above all by a calculus of costs and benefits. All the mathematical equations by which economists bedazzle their clients, or the public, are founded on one simple assumption: that everyone, left to his own devices, will choose the course of action that provides the most of what he wants for the least expenditure of resources and effort. It is the simplicity of the formula that makes the equations possible: if one were to admit that humans have complicated motivations, there would be too many factors to take into account, it would be impossible to properly weight them, and predictions could not be made. Therefore an economist will say that while of course everyone is aware that human beings are not really selfish, calculating machines, assuming that they are makes it possible to explain a very large proportion of what humans do, and this proportion – and only this – is the subject matter of economic science.

This is a reasonable statement as far as it goes. The problem is there are many domains of human life where the assumption clearly doesn’t hold – and some of them are precisely in the domain of what we like to call the economy. If “minimax” (minimise cost, maximise benefit) assumptions were correct, people in bullshit jobs would be delighted with their situation. Consider Eric, for example. He was receiving a lot of money for virtually zero expenditure of resources and energy – basically bus fare, plus the amount of calories it took to walk around the office and answer a couple of calls. Yet all the other factors (class, expectations, personality, and so on) don’t determine whether someone in that situation would be unhappy – since it would appear that just about anyone in that situation would be unhappy. They only really affect how unhappy they will be.

Much of our public discourse about work starts from the assumption that the economists’ model is correct. People have to be compelled to work; if the poor are to be given relief so they don’t actually starve, it has to be delivered in the most humiliating and onerous ways possible, because otherwise they would become dependent and have no incentive to find proper jobs. The underlying assumption is that if humans are offered the option to be parasites, of course they’ll take it.

In fact, almost every bit of available evidence indicates that this is not true. Human beings certainly tend to rankle over what they consider excessive or degrading work; few may be inclined to work at the pace or intensity that “scientific managers” have, since the 1920s, decided they should; people also have a particular aversion to being humiliated. But leave them to their own devices, and they almost invariably rankle even more at the prospect of having nothing useful to do.

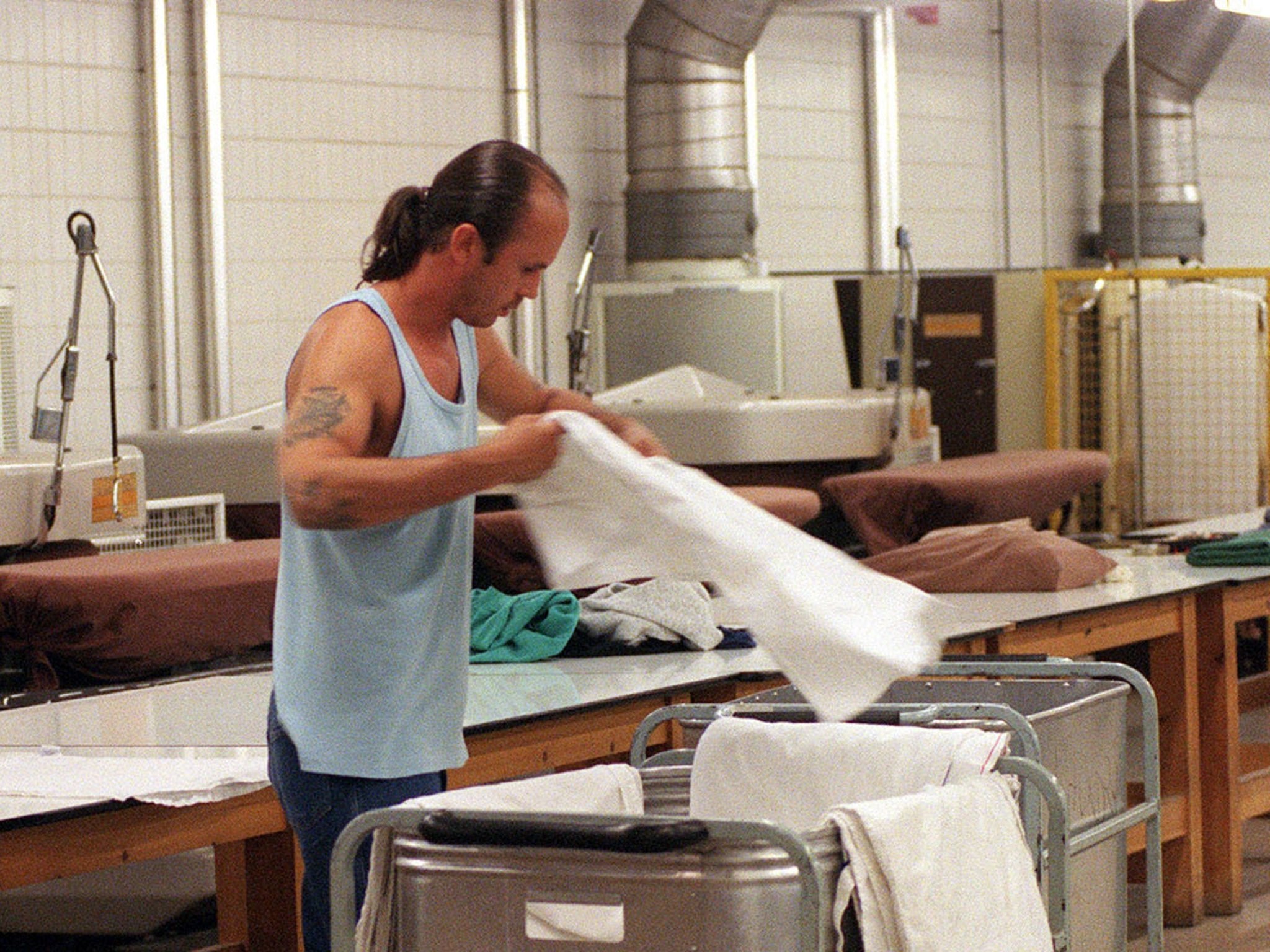

There is endless empirical evidence to back this up. To choose a couple of particularly colourful examples: working-class people who win the lottery and find themselves multimillionaires rarely quit their jobs (and if they do, usually they soon say they regret it). Even in those prisons where inmates are provided free food and shelter and are not actually required to work, denying them the right to press shirts in the prison laundry, clean latrines in the prison gym, or package computers for Microsoft in the prison workshop is used as a form of punishment – and this is true even where the work doesn’t pay or where prisoners have access to other income. Here we are dealing with people who can be assumed to be among the least altruistic society has produced, yet they find sitting around all day watching television a far worse fate than even the harshest and least rewarding forms of labour.

The redeeming aspect of prison work is, as Dostoyevsky noted, that at least it was seen to be useful – even if it is not useful to the prisoner himself. Actually, one of the few positive side effects of a prison system is that, simply by providing us with information of what happens, and how humans behave, under extreme situations of deprivation, we can learn basic truths about what it means to be human. To take another example: we now know that placing prisoners in solitary confinement for more than six months at a stretch inevitably results in physically observable forms of brain damage. Human beings are not just social animals; they are so intrinsically social that if they are cut off from relations with other humans, they begin to decay physically.

I suspect the work experiment can be seen in similar terms. Humans may or may not be cut out for regular nine-to-five labour discipline – it seems to me that there is considerable evidence that they aren’t – but even hardened criminals generally find the prospect of just sitting around doing nothing even worse.

Why should this be the case? And just how deeply rooted are such dispositions in human psychology? There is reason to believe the answer is: very deep indeed.

As early as 1901, the German psychologist Karl Groos discovered that infants express extraordinary happiness when they first figure out they can cause predictable effects in the world, pretty much regardless of what that effect is or whether it could be construed as having any benefit to them. Let’s say they discover that they can move a pencil by randomly moving their arms. Then they realise they can achieve the same effect by moving in the same pattern again. Expressions of utter joy ensue. Groos coined the phrase “the pleasure at being the cause”, suggesting that it is the basis for play, which he saw as the exercise of powers simply for the sake of exercising them.

This discovery has powerful implications for understanding human motivation more generally. Before Groos, most Western political philosophers – and after them, economists and social scientists – had been inclined either to assume that humans seek power simply because of an inherent desire for conquest and domination, or else, for a purely practical desire to guarantee access to the sources of physical gratification, safety, or reproductive success. Groos’s findings – which have since been confirmed by a century of experimental evidence – suggested maybe there was something much simpler behind what Nietzsche called the “will to power.” Children come to understand that they exist, that they are discrete entities separate from the world around them, largely by com- ing to understand that “they” are the thing which just caused something to happen – the proof of which is the fact that they can make it happen again. Crucially, too, this realisation is, from the very beginning, marked with a species of delight that remains the fundamental background of all subsequent human experience. It is hard perhaps to think of our sense of self as grounded in action because when we are truly engrossed in doing something – especially something we know how to do very well, from running a race to solving a complicated logical problem – we tend to forget that we exist. But even as we dissolve into what we do, the foundational “pleasure at being the cause” remains, as it were, the unstated ground of our being.

Groos himself was primarily interested in asking why humans play games, and why they become so passionate and excited over the outcome even when they know it makes no difference who wins or loses outside the confines of the game itself. He saw the creation of imaginary worlds as simply an extension of his core principle. This might be so. But what we’re concerned with here, unfortunately, is less with the implications for healthy development and more with what happens when something goes terribly wrong. In fact, experiments have also shown that if one first allows a child to discover and experience the delight in being able to cause a certain effect, and then suddenly denies it to them, the results are dramatic: first rage, refusal to engage, and then a kind of catatonic folding in on oneself and withdrawing from the world entirely. Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Francis Broucek called this the “trauma of failed influence” and suspected that such traumatic experiences might lie behind many mental health issues later in life.

If this is so, then it begins to give us a sense of why being trapped in a job where one is treated as if one were usefully employed, and has to play along with the pretence that one is usefully employed, but at the same time, is keenly aware one is not usefully employed, would have devastating effects. It’s not just an assault on the person’s sense of self-importance but also a direct attack on the very foundations of the sense that one even is a self. A human being unable to have a meaningful impact on the world ceases to exist.

Boss: How come you’re not working?

Worker: There’s nothing to do.

Boss: Well, you’re supposed to pretend like you’re working.

Worker: Hey, I got a better idea. Why don’t you pretend like I’m working? You get paid more than me.

– Bill Hicks comedy routine

Groos’s theory of “the pleasure at being the cause” led him to devise a theory of play as make-believe: humans invent games and diversions, he proposed, for the exact same reason the infant takes delight in his ability to move a pencil. We wish to exercise our powers as an end in themselves. The fact that the situation is made up doesn’t detract from this; in fact, it adds another level of contrivance. This, Groos suggested – and here he was falling back on the ideas of Romantic German philosopher Friedrich Schiller – is really all that freedom is. (Schiller argued that the desire to create art is simply a manifestation of the urge to play as the exercise of freedom for its own sake as well.) Freedom is our ability to make things up just for the sake of being able to do so.

Yet at the same time, it is precisely the make-believe aspect of their work that student workers find the most infuriating – indeed, that just about anyone who’s ever had a wage-labour job that was closely supervised invariably finds the most maddening aspect of her job. Working serves a purpose, or is meant to do so. Being forced to pretend to work just for the sake of working is an indignity, since the demand is perceived – rightly – as the pure exercise of power for its own sake.

If make-believe play is the purest expression of human freedom, make-believe work imposed by others is the purest expression of lack of freedom. It’s not entirely surprising, then, that the first historical evidence we have for the notion that certain categories of people really ought to be working at all times, even if there’s nothing to do, and that work needs to be made up to fill their time, even if there’s nothing that really needs doing, refers to people who are not free: prisoners and slaves, two categories that historically have largely overlapped.

David Graeber is a professor of anthropology at LSE. 'Bullshit Jobs: A Theory' is published by Simon and Schuster

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks