Has the forward march of Corbynism been halted?

Jeremy Corbyn succeeded because he defined himself as against the system: but now, with the party split and his message on the wane, the strategy may have come unstuck, says John Rentoul

It is odd that the two main parties should be splintering now. It looks as if the imminent crunch of leaving the EU has finally forced party loyalties to break. But the paradox is that, as Anna Soubry admitted, none of this week’s defections changes the parliamentary arithmetic on Brexit. What is more, “the last thing this country needs is a general election” to change that arithmetic, Soubry added.

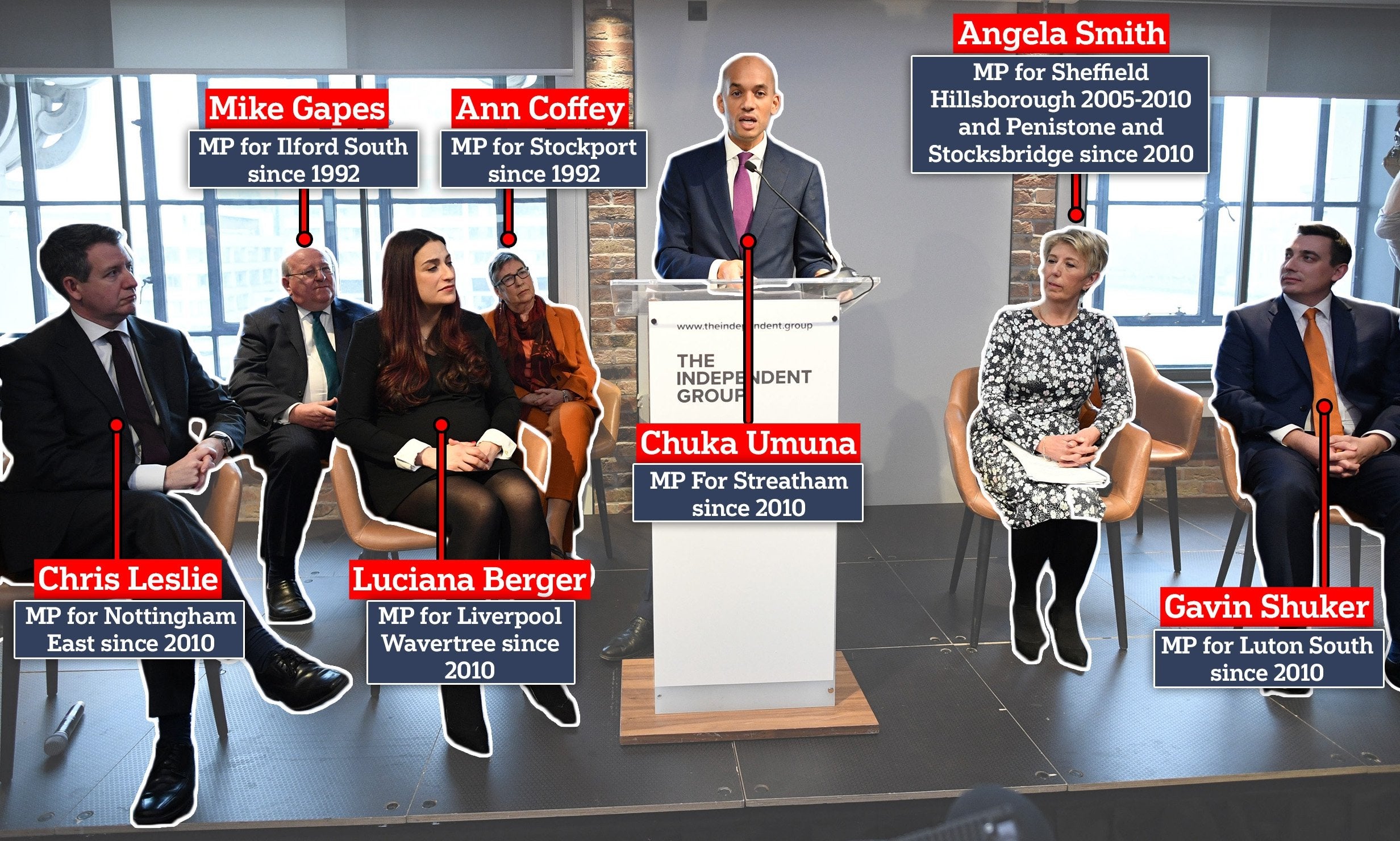

But the causes of the defections from both main parties go beyond Brexit, and the implications of the launch of the Independent Group of MPs are more for Jeremy Corbyn than for the prime minister.

After all, the Conservative Party doesn’t intend to fight the next election under Theresa May’s leadership, whereas Labour Party members are eager and hopeful to see Corbyn try to repeat the trick of exceeding expectations that he pulled off last time.

The true significance of the Independent Group could be that it marks the point at which the forward march of Corbynism was halted. For three and a half years Corbyn has defied all challenges and overcome them. Three times he seemed to be becalmed, facing defeat and yet he surprised everyone – including himself.

When he agreed, with the mock reluctance that is still required in old-fashioned socialist circles, to allow his name to be put forward for the party leadership, he did not expect to attract enough nominations to be a candidate, let alone to win. But he was the authentic outsider against the system. That was a message whose time had come.

The membership surge he attracted produced more revenue for the party than it had known for many years – never mind the myth of £3 registered supporters, most of the new recruits paid full fare – which meant he took over a party that was suddenly solvent.

In the election campaign Corbyn and Seumas Milne promised change versus more of the same, the oldest dividing line in democratic history, and their anti-establishment pitch succeeded beyond their wildest dreams

However, the rise in membership numbers stalled, and Corbyn faced a revolt of Labour MPs after he appeared to welcome the result of the 2016 EU referendum. He brushed off a vote of no confidence by his parliamentary party and the mass resignations of shadow ministers. But then, faced with a challenge from Owen Smith, he fought a second leadership election, attracting a second surge of new members, taking the party over the half-million mark.

The respite was short. His standing, and that of his party, in opinion polls drifted as Theresa May continued to enjoy a halo effect as a new prime minister. Twenty points ahead, she went to the country to ask for a mandate of her own to negotiate our departure from the EU.

Corbyn held his nerve and Seumas Milne, the executive director of strategy and communications for the Labour Party, stuck to his strategy. The strategy that Milne directs, as his grandiose job title has it, and which he helps the leader to communicate, is simple: to keep Corbyn Labour on brand, the brand being “against the system”.

In the election campaign Corbyn and Milne simply ignored Brexit and focused on the accumulated discontents of seven years of fiscal stringency: policing, housing, schools and the NHS. They promised change versus more of the same, the oldest dividing line in democratic history, and their anti-establishment pitch succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

Everything that was thrown at the Labour leader was turned into a strength. His anti-Americanism was turned into an argument that a US-led foreign policy had made Britain a target for terrorism. His hostility to private enterprise was turned into a plan to nationalise resented utility companies. And his interest in Latin American Marxism and the history of Irish republicanism were just badges of his authenticity.

On election night, before the exit poll was announced, Corbyn asked his inner team to predict the result. Milne was among those who predicted a large Conservative majority, with only Karie Murphy, Corbyn’s chief of staff, expecting to accompany the leader to Buckingham Palace the next day.

As it was, Corbyn and Murphy didn’t go to the palace, but Labour gained seats rather than losing them, and, although it fell just short of preventing a Tory-DUP majority, defeat seemed like a victory. Milne’s presentation of Corbyn as the authentic outsider enjoyed its finest hour.

It was surprising that Corbyn and his inner circle did so little to avert the split

For all his time as leader, the strategy of being “against the system” has worked a treat. Sticking to the brand helped him hold together the Remain-heavy Labour coalition of Remainers and Leavers. The most vociferous Remainers were identified with the Blairite elite, so Corbyn kept his distance while favouring a softer Brexit than the government’s. That allowed Remainers to vote for him in 2017 while allowing the main campaign to focus on other things.

It was only this year that the Milne strategy came unstuck. Corbyn’s aides could see May’s offer of cross-party talks on Brexit coming a mile off. They knew she would have to put her deal to parliament and that it would be defeated by a large margin. As the moment approached, was put off and then approached again, they expected the prime minister – the moment the result of the vote was announced – to invite opposition MPs, including the leaders, to talk to her about the way forward.

As they discussed how Corbyn should respond, they stuck to the strategy that had served them so well. Corbyn should refuse to talk to the prime minister, the personification of the establishment, unless she agreed to his demand for a permanent customs union. They knew she would refuse, not least because her party would become unmanageable if she agreed, so they believed Corbyn would appear reasonable and yet keep his hands clean by not fraternising with the enemy.

It was a mistake. Public opinion was strongly in favour of cross-party talks and even Corbyn-supporting Labour members were confused and uncertain.

We cannot say what part this decision played in the the fall in Corbyn’s personal ratings, but it preceded it by two weeks. At the start of this month 72 per cent of voters said they were dissatisfied with the way Corbyn was doing his job as leader of the opposition, and only 17 per cent were satisfied. The net score of minus 55 points was the worst of any opposition leader since Michael Foot in August 1982, on minus 56.

So now Corbyn is up against it again. Membership numbers are still high, but they are drifting downwards. And now the party has finally split. Make no mistake; this is a significant moment.

Corbyn and Milne had been worried about Labour MPs defecting for some time. They realised how serious a threat a breakaway would be. Despite the defection of three Conservative MPs, the proto-party is likely to take more votes away from Labour than the Tories.

It was surprising, therefore, that Corbyn and his inner circle did so little to avert the split. They dropped disciplinary action against Margaret Hodge, who called Corbyn a racist to his face, and I suspect the leader’s office intervened in Liverpool Wavertree to persuade Luciana Berger’s local party to drop its motions of no confidence in her (yes, the London elite overruling authentic expression of local anti-establishment sentiment).

Corbyn said he regretted the defectors were now going ‘somewhere else’. That paints them as rebels and him as the authority figure – quite apart from prompting hollow laughter about his attitude to Labour manifestos in the past

But that was after John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, had already done the damage of saying, in effect, that all Berger had to do to get him to call off the thought police was to declare that she loved Big Brother. In an interview on the Today programme, he said: “My advice is for Luciana to just put this issue to bed; say, very clearly: ‘No, I’m not supporting another party; I’m not jumping ship.’”

After the split happened, however, it was no surprise that Milne’s response was to return to his one-note strategy. A “spokesman for Corbyn” said the Labour defectors are now part of an “establishment coalition” that backs privatisations and corporate tax cuts. But the Labour leader now looks like part of the existing system and it is the defectors who look like the insurgents.

Corbyn pointed out that the defectors stood on his manifesto in 2017 and said he regretted that they were now going “somewhere else”. That paints them as rebels and him as the authority figure – quite apart from prompting hollow laughter about his attitude to Labour manifestos in the past.

But it also underlines how exceptional the 2017 election was. The only reason Labour didn’t split then was that the election came as a surprise and MPs, certain that Corbyn wouldn’t win, wanted to preserve their jobs by holding their seats.

But none of the conditions that applied then will apply to the next election. Theresa May will not be the Tory leader. So the disastrous campaign the Tories fought last time is unlikely to be repeated – although there are more ways to mess up than to succeed. More importantly, a new leader, in a post-Brexit Britain, would find it easier to shake off the loss of a handful of pro-EU Tory MPs than Corbyn will to move on from his own defections.

It will be harder for Corbyn to exceed expectations a second time. Who knows how much damage the Independent Group will inflict on the Labour Party by then? Everyone is fond of pointing out that the electoral system is likely to punish the new party, which is a good point, and the history of the Social Democratic Party bears it out, but it is too late now.

The breakaway has happened. They may not succeed but they can still do a great deal of damage in the attempt. The hopelessness of the enterprise only adds to the emotional power of the story. This will be a subplot in politics for some time to come, and it is mostly going to be bad news for Corbyn.

Yes, Corbyn has turned things round before. He has been underestimated before, including by me. But he is going to be an establishment figure by the time of the next election. It seems that the power of his “against the system” message is waning.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks