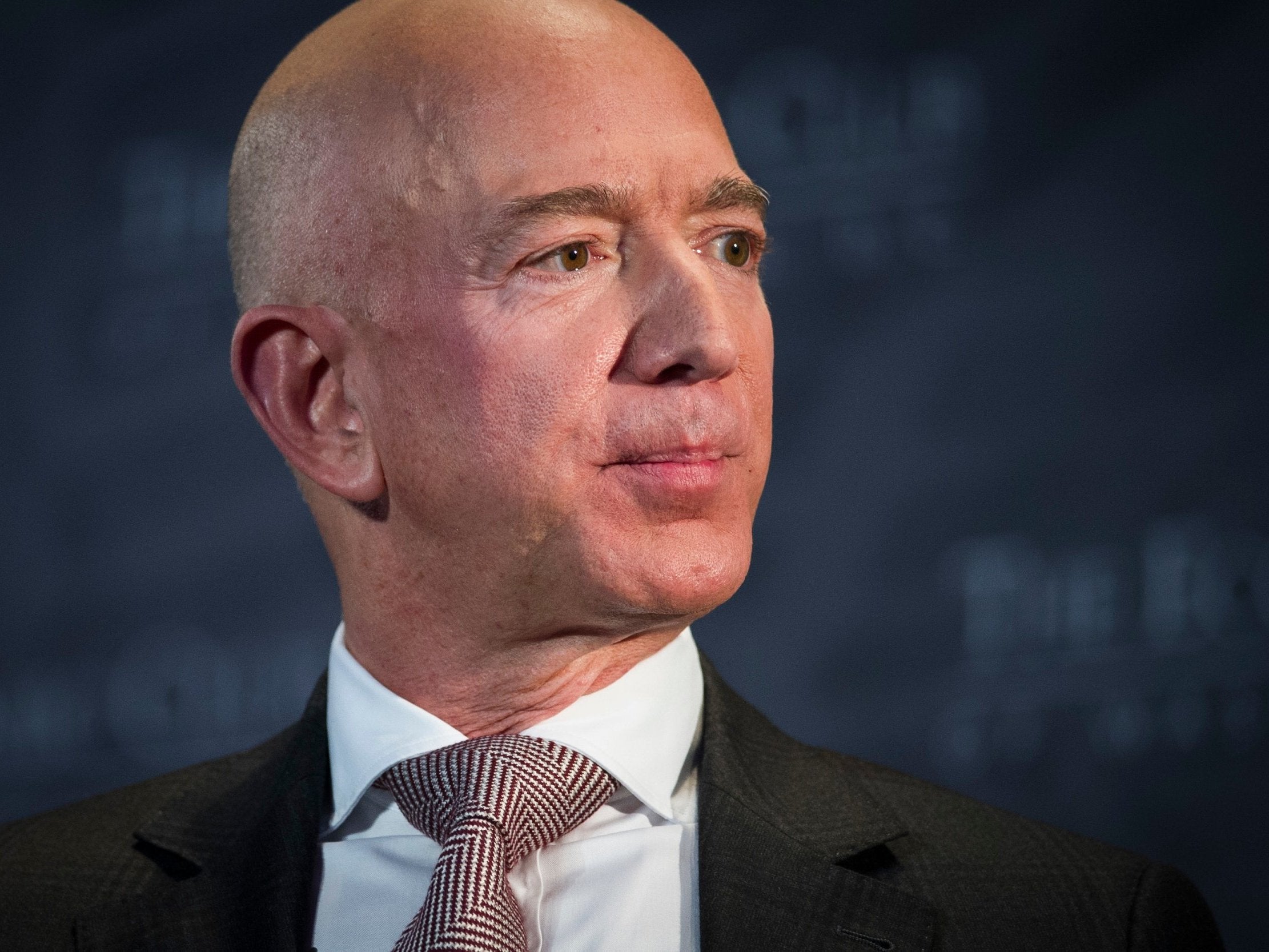

From humble beginnings to master of the universe: How did Jeff Bezos make his billions?

A big part of the answer is his frugality – but he also has a knack for knowing when to put his neck on the line and when to keep his head down. Josie Cox explains

When Jeffrey Preston Jorgensen was three years old, he reportedly dismantled his cot with a screwdriver because he desperately wanted to sleep in a proper bed. While no doubt annoying for his probably startled parents, it may well have been one of the first indications that precocious young Jeff was not your average kid growing up in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Biographies of the now 55-year-old describe his striking mechanical aptitude at a very young age. After the cot incident, he is said to have rigged up an electric alarm to keep his younger siblings out of his bedroom, and later he converted his parents’ garage into a lab for his quirky science projects.

Ambition and creativity morphed into academic excellence. Jeff attended high school in Miami where he graduated top of his class and then went to Princeton University, where he earned a degree in computer science and electrical engineering, a qualification that swiftly secured him a job at a top bank on Wall Street.

And the story could have ended there. Jeff was a skilled financier and quickly rose up the totem pole of capitalism. With a brain for computers, he could have ridden the wave of the tech boom and probably shouldered the crash, earning handsomely and securing a luxurious future for his wife and children. But it wasn’t meant to be. The internet got in the way, so to speak, and now Jeff is one of the richest people ever to have walked the earth. With a market value not far off $1 trillion, his empire, Amazon, is one of the largest companies ever to have existed and even the sky doesn’t seem to be the limit.

It started with an A

For today’s startup-obsessed world, the story of Amazon is a tonic of hope. Jeff Bezos, who took his Cuban immigrant stepfather’s name when his mother remarried in 1968, was driving in his car from New York to Seattle in 1993 when he started sketching out a business plan.

The internet, though enjoying stratospheric growth, was not being used for commercial purposes, and Bezos couldn’t understand why. He analysed the country’s top mail-order businesses and evaluated which of them might be able to function more efficiently with the help of the world wide web. Books, Bezos concluded, were perfect. There were too many of them in the world to create a comprehensive mail order catalogue so the Internet was an obvious platform.

The following year Bezos quit his job at hedge fund DE Shaw, where he had risen to the position of senior vice-president, and started his venture. Several names were in the running and he eventually settled on “Cadabra” – as in Abracadabra. Later, Bezos’s lawyer is said to have vetoed the name for its unfortunate association with the word “cadaver”. Amazon.com – allegedly inspired by the river and because it starts with the first letter of the alphabet – was born, but fuelled by his fondness for the name “Relentless”, another close contender, Bezos bought that domain name too. To this day, landing on www.relentless.com will redirected you to the e-commerce giant’s platform.

Tales of Amazon’s formative years are charmingly humble. According to some accounts, Bezos, his wife MacKenzie (from whom he recently split) and Amazon’s first employee, Shel Kaphan, held their early meetings at a local Barnes and Noble store. There’s tragic irony in the fact that years later, Amazon became a prime threat to the existence of the high street stalwart that first started selling books back in 1873.

$17bn

The revenue from Amazon Web Services in 2017

Amazon went public in May 1997, raising $54m on the stock exchange by selling around three million shares, which in turn gave the company a market value of about $438m. Underscoring investors’ fierce appetite for tech, shares in the company soared by 30 per cent on their first trading day, setting the firm up for aggressive growth. In 1998 Amazon started selling music and videos and expanded internationally by snapping up booksellers in the UK and Germany, which are still the company’s two biggest international markets, ahead of Japan. Not long after that, it moved into video games, toys, consumer electronics, software and other miscellaneous items. One particularly important milestone for the company was its 2002 launch of Amazon Web Services, a provider of cloud computing platforms, which can be used by companies and individuals on a subscription basis. Revenue of AWS alone hit more than $17bn in 2017.

Amazon’s suite of products and services is now sprawling. Amazon Fresh and Amazon Prime cater to today’s generation of on-demand shoppers who want instant service at the click of a button. With the Kindle and Fire tablets, as well as Audible and Goodreads, the company has tapped into a new appetite for consuming media. Alexa and Echo are Bezos’s answer to the emergence of the Internet of Things: smart homes and intelligent living. The company also has a large robotics division and owns the international film database IMDb. Its portfolio includes a slew of other media outlets too, including cloud-based digital comics platform ComiXology, CreateSpace, a self-publishing service, and live streaming platform Twitch.

In September 2018, Amazon followed Apple to become the second company ever to hit a market value of more than $1 trillion, easily making Bezos, who at the time owned over 15 per cent of the company, the world’s richest person. His current net wealth is estimated to be around $132 billion, ahead of Bill Gates at $96 billion, and Warren Buffett, at just over $83 billion.

The internet and beyond

For many corporations competing in an increasingly connected world, the internet presented a new dimension for growth once opportunities in the real world dried up. For Amazon, the reverse has been true.

$132bn

Bezos’s current net wealth

In 2015 the pioneer of e-commerce opened its first physical book shop in Seattle, but its largest bet on the future of bricks-and-mortar retail came in 2017 when it snapped up upmarket grocer Whole Foods for $13.7bn, giving it ownership of more than 450 shops across the US, Canada and the UK. Last year the first Amazon Go opened its doors in Seattle, a convenience store that now has outlets in Chicago and San Francisco too.

Amazon’s recent commitment to physical shops has confounded some analysts, but Natalie Berg, who co-authored a recent book about the company, considers the move rational. Amazon, she says, loves to disrupt. The company has recognised that the experience consumers are currently being offered in many physical shops is outdated and inefficient. Like it did with the internet, Amazon wants to shake things up.

Berg also explains that while shoppers – especially the younger – are flocking online for convenience, very few people make all their purchases online. Her theory is that the future of retail will be a blend of both online and offline. By diversifying, Amazon aims to straddle both worlds, according to Berg. And there are some product classes, like fashion, that are unlikely to ever lend themselves exclusively to an online audience.

“Quality is subjective and cannot be determined over a screen,” Berg recently told Forbes. In fact, she predicts that while Amazon has yet to open any clothes shops of its own, this could well be next on the cards.

The Bezos touch

So how did Bezos, who also owns The Washington Post, manage it? How did precocious Jeff from Albuquerque grow one of the world’s biggest companies that touches on practically every corner of consumerism? How did he manage to steer the ultimate dotcom venture through the disastrous dotcom bust? And how, unlike so many of his entrepreneur peers, did he succeed in morphing from visionary founder with a seemingly unbridled appetite for risk, to captain of a global multinational empire with more employees than many cities? The answer might be his faultless ability to know when to spend and when to save; when to put his neck on the line and when to keep his head down; when to be cowed and when to speak up.

Though Amazon sales soared from $15.7m in 1996 to $147.8m in 1997, the company was almost capsized by its rate of spending. In 1999, it generated revenue of $1.6bn but chalked up a loss of $719m. Financial filings show that the company was almost completely floored when the tech bubble started to burst, and at one point in 2000 only had $350m of cash left in its coffers.

Bezos and his team borrowed $2bn from banks to stay afloat, a bold and likely painful move at a time of global financial stress, but a savvy decision all the same. The chief executive also bit the bullet by recognising the need for savings in the long run: he shuttered several large distribution centres and axed about a seventh of global staff. In 2003, as many e-commerce competitors were still licking their wounds from the crash, Amazon breathed a cautious sigh of relief as it turned its first ever profit.

To this day, one of Amazon’s core values is frugality. In 1995, when Bezos was furnishing his first office to accommodate a handful of early employees, he noticed that at the Home Depot across the street doors were on sale at a significantly cheaper price than desks.

The scrappy do-it-yourself desk is one of Amazon’s most iconic bits of culture, representing ‘ingenuity, creativity, and the willingness to go on your own path’

So, according to employee number five, Nico Lovejoy, Bezos simply bought a door and stuck legs on it. The scrappy, do-it-yourself piece of furniture is now one of Amazon's most iconic bits of culture and according to an internal blog, thousands of employees worldwide still work on a modernised version of the so-called door-desk today. In recent years Amazon has even launched the Door-Desk Award internally to recognise ideas that help deliver low prices to customers. Lovejoy says that for him it represents “ingenuity, creativity and peculiarity, and the willingness to go your own path” – all qualities that Bezos no doubt has in abundance.

The next frontier

As Amazon enters its 25th year, Bezos is once again displaying his ability to balance risk and ambition, creativity and reason. Over the past few years, he’s been selling chunks of his personal stock holding in Amazon to raise cash for new ventures.

At a dinner in New York in March last year, the CEO said in a speech that the “price of admission to space is very high”, then continued: “I’m in the process of converting my Amazon lottery winnings into a much lower price of admission so we can go explore the solar system.” And Bezos wasn’t exaggerating.

When he was in high school he already expressed a desire to create colonies for human beings in orbit, and in 2000 he founded a space flight startup called Blue Origin. Initially the company maintained a low profile, but in 2006 it reportedly bought a large area of land in Texas as a test facility. Publicity was somewhat dented in September 2011 when one of Blue Origin’s unmanned vehicle crashed during a test flight, but the fact that the company was already developing prototypes of this standard was praised internationally.

Several years later, in November 2015, Blue Origin successfully launched a space vehicle called New Shepard into orbit and landed it. Dummy passengers took their first flight in New Shepard in December 2017 and development has continued since. Bezos has spoken freely and on many occasions about his ambitions to colonise the solar system, maintaining that his ultimate goal is to preserve the natural resources of the earth by allowing the human race to exist on many planets.

Beyond this, he’s also demonstrating a very personal ability to navigate politics and business simultaneously, another quality that distinguishes him as a true corporate pacesetter of the modern age.

In early February, in what would be a bizarre move for any top corporate exec, Bezos published a blog post accusing the publisher of the National Enquirer of “extortion and blackmail”. He said the publication had threatened to post revealing photographs of him unless he publicly affirmed the paper’s reporting of him was not politically motivated.

Not long after Bezos announced that he was splitting from his wife MacKenzie, the National Enquirer published “intimate text messages” revealing the billionaire’s relationship with a former TV anchor called Lauren Sánchez.

With his public blog post, Bezos called out the National Enquirer and the owner of its parent company (who happens to be a close ally of Donald Trump) and announced that he was not prepared to stoop so low as to play political games. He communicated that he’s above that, and quickly became the good guy in the whole sorry saga of selfies and scandal.

The message now is clear. Though Bezos is merely human, he’s not to be messed with. He’s taken over the internet. His next mission is space, and if you try to take him on, you’re unlikely to win. His current empire may be called Amazon, but remember the domain name that he bought and still owns, just because he likes it. Nomen – as they say – est omen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments