How Jamie Reid’s iconoclastic album covers for the Sex Pistols became a symbol of British punk

The band’s album covers became just as symbolic of the British punk movement as their raucous anthems. But, ‘there’s a lot more to my work than punk PR’, the artist behind them, Jamie Reid, tells William Cook

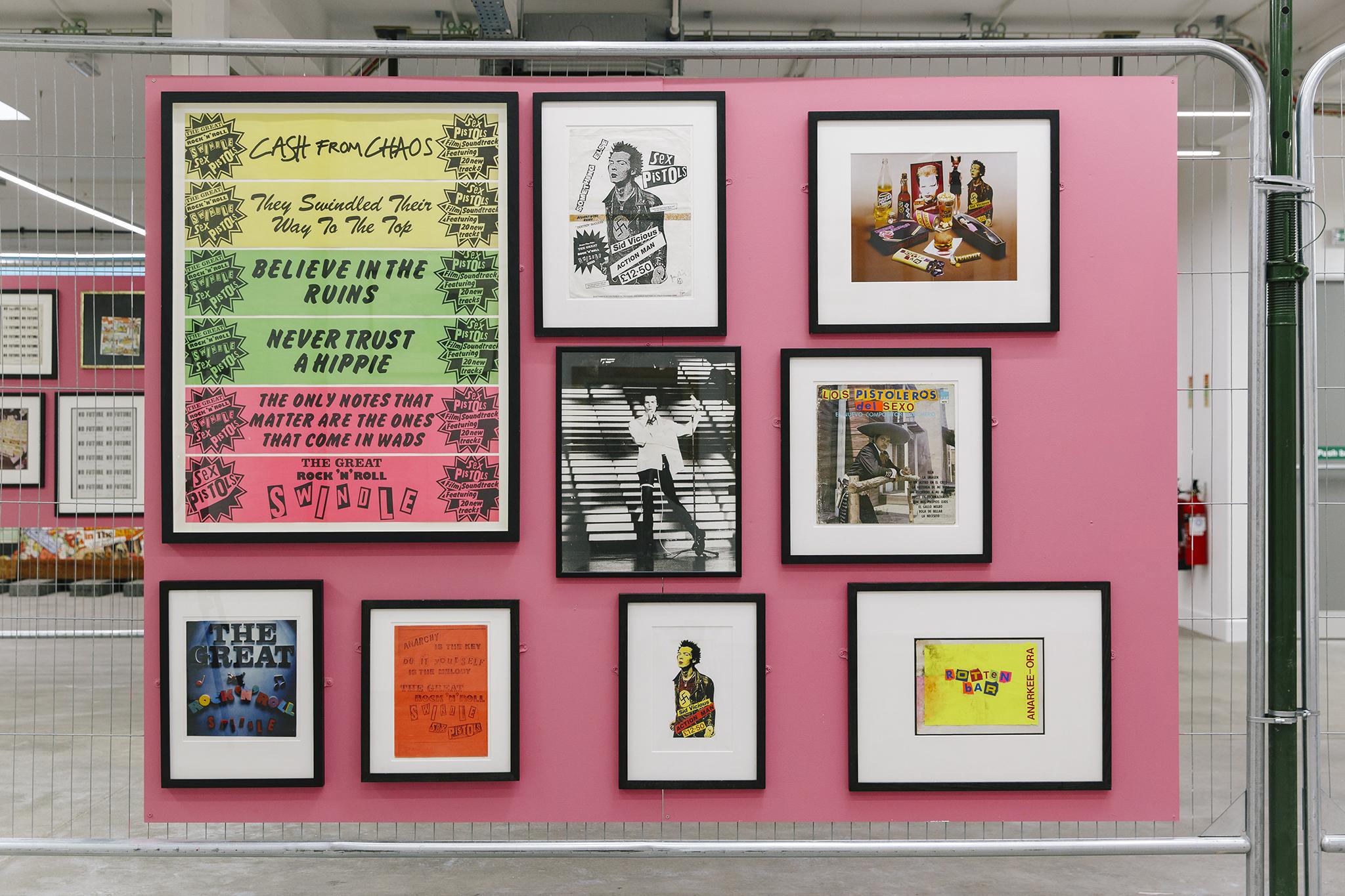

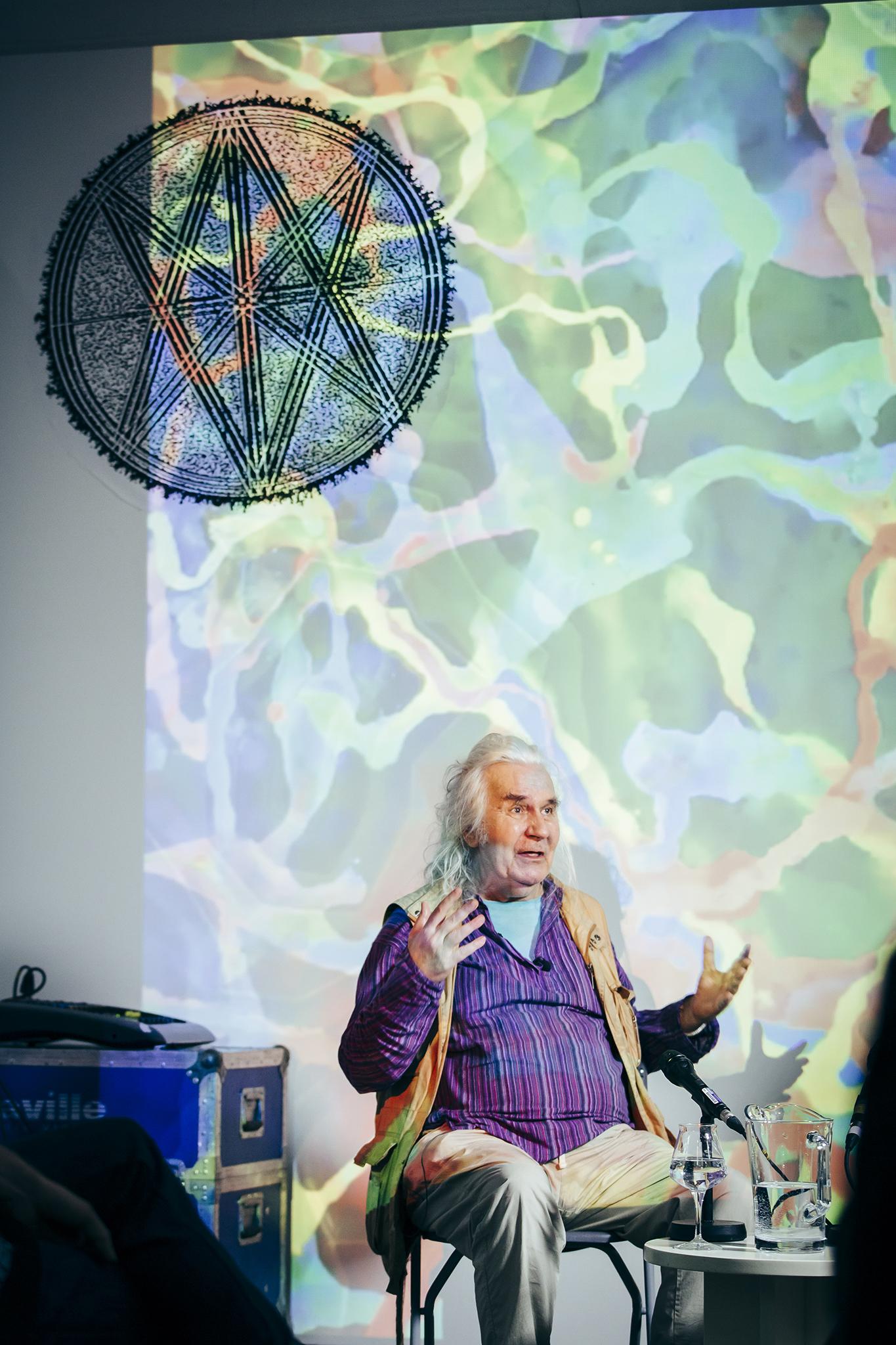

Here at Humber Street Gallery on Hull’s historic waterfront, Jamie Reid is busy assembling his biggest ever one-man show. It’s a diverse display, spread across three floors of this old warehouse, encompassing everything from situationist propaganda to new age spirituality. It’s the old punk slogans that leap off the walls though: “Cash from Chaos”; “Demand the Impossible”; “Never Trust a Hippy”. Jamie Reid has been making art for 50 years, and this is his most comprehensive retrospective. However, somewhat to his own chagrin, he’s destined to be remembered for a few record sleeves and posters he made in the 1970s for a short-lived punk band called the Sex Pistols. As Johnny Rotten once said: “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”

The Sex Pistols’ raucous anthems became the soundtrack of 1970s counterculture – a furious backlash against cosy conformity – and the artwork Reid created to promote them was almost as important as the music. His iconoclastic designs channelled that anger into art. The union jack has never looked quite the same since he ripped it up to promote the Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK”. Her Majesty has never looked quite the same since Reid put a safety pin through her top lip to promote the Pistols’ “God Save the Queen”.

Of course there’s a lot more to his work than punk PR, and this retrospective bears that out. Some of his agit-prop preceded punk; some of it came much later, like his Free Pussy Riot poster featuring Putin in a balaclava. His new age stuff is entirely different – you’d never guess it was by the same artist: dreamy abstract designs which wouldn’t look out of place on a prog rock gatefold sleeve. Yet it’s the slogans that stand out, and there are lots I’ve never seen before: “Keep Warm this Winter – Make Trouble”; “Save Petrol – Burn Cars”; “City of Culture, My Arse” (a nice irony, here in last year’s UK cultural capital) and a new take on an old favourite, “Never Trust A Punk”.

Wandering around this exhibition, you can see why Reid gets fed up when people just want to ask him about the Sex Pistols. His work is far broader, and it stretches much further back: to dada and the bauhaus, and the political collage of John Heartfield. So where did his anarchic house style come from? I went to Liverpool, his adopted hometown, to try to find out.

We meet at the Florrie, a community centre in the Dingle, one of Liverpool’s poorest districts (Ringo Starr and Gerry Marsden both grew up around here). Reid is an ardent advocate of this beautiful building, an oasis of culture and companionship in a community that’s taken quite a battering. Formerly a burnt-out ruin, the Florrie provides everything from free art classes for local adults to free meals for local kids. His artworks adorn the walls.

For Reid, the Florrie is an antidote to what he sees as the gentrification of the arts – in particular, high-profile schemes such as Liverpool’s tenure as European Capital of Culture, “which, to me, was outside people designating lots of money to outside artists”. The way he sees it, local artists never got a look-in. “I think they were frightened to rock the boat.” He wasn’t born in Liverpool, but he’s lived here for over half his life, and although his accent is still Sarf London, you can tell he’s now a Liverpudlian at heart. He moved to Liverpool with the Scouse actor Margi Clarke, with whom he had a daughter, Rowan. Jamie and Margi are no longer together, but Jamie and Rowan are close.

“I don’t want to rant and rave too much,” he says, when we sit down together at a corner table in the Florrie’s cosy cafe. I tell him to go right ahead. His manner is wary, but his opinions are forthright. With his long white hair and his intense stare, he looks more like a druid than a punk.

“I’m inevitably going to be associated with the Pistols and punk,” he tells me. “People can’t see how I can do the spiritual stuff and the agit-prop stuff, but I’ve always seen that as part and parcel of the same thing.”

He was born in Croydon in 1947. His father was City editor of the Daily Sketch, back in the good old days when journalism was still an unfashionable, unpretentious trade. Despite his dad’s capitalist career, both his parents were committed socialists. “From an early age, I was dragged along to the Aldermaston marches – which I loved.” Anti-war protest ran in the family: his mother was a passionate supporter of CND; his big brother was in the Committee of 100. “He was actually put on trial for treason,” says Jamie, proudly.

Jamie went to the local grammar school, where he shone at sport, but he left at 16 with no qualifications. Yet he’d always enjoyed drawing, and he managed to get into Croydon College of Art, where he met a young art student called Malcolm McLaren. Politically and personally, they hit it off straight away. It was 1968, the summer of revolt, and the student riots in Paris were a big inspiration. They staged their own sit-in, like the one at LSE.

After art school, Reid began writing and making artwork for a radical journal he ran called Suburban Press. “We couldn’t really afford things like Letraset, so it seemed natural to cut things out and do collage, to save money.” What started as something purely practical soon became a kind of brand. Five years before punk, this was how his ransom note style evolved.

Suburban Press was strongly influenced by situationism, a heady blend of Marxism, anarchism and surrealism – “questioning everything you’re told to take as being fact, in terms of the way you’re educated, and the way politics is presented to you”. However, Reid could see that, to the uninitiated, these wordy theories seemed opaque. Suburban Press translated these complex ideas into simple language and dramatic imagery. Illustrated by tabloid cut-ups that subverted the mainstream media, it was like a populist newspaper that had been hijacked by Left Bank intellectuals.

Reid didn’t stop at publishing. His artwork spilled over into direct action. He fly-posted Oxford Street with posters that read “This Store Welcomes Shoplifters”. This was before CCTV, so he got away with it, but the powers-that-be took an interest. “We knew our phone was tapped,” he says.

After five years publishing Suburban Press, he felt ready for a change of scene. “At that time there was quite a lot of people who just wanted to move out of cities and be self-sufficient,” he explains. Some of his friends became crofters on the Isle of Lewis, and Reid travelled up to join them. However, this was no new age nirvana. Reid uses one word to describe it: “Bleak.”

Thankfully, he was rescued from this rural purgatory by a telegram from his old art school pal Malcolm McLaren, reading: “Would you be interested in working with this band I’ve got called the Sex Pistols?”

Reid needed no persuading. He travelled to Soho and started straight away. “I had a completely free rein to do what I wanted. A lot of it was perpetuating the things that I was doing at Suburban Press.” The first single, “Anarchy in the UK” (with Reid’s union jack record sleeve) caused a sensation. The second single, “God Save the Queen” (with Reid’s punk monarch) took this succès de scandale to another level. For half the country, it was an outrage. For the other half, it was a rebellious riposte to the shallow pomp of the Silver Jubilee. “The fact that that record actually got to number one in the hit parade in the week of the jubilee was amazing. It showed there was a groundswell of popular belief in what we were trying to put across.”

Everything happened so fast, it all became a blur. “We were in another world. There you are, doing an artwork, and it’s instantly on the front page of the Daily Mirror.” One of McLaren’s most successful stunts was staging a Sex Pistols gig on a riverboat on the Thames outside parliament. Reid was there when the police came aboard to break up the party. “They knew exactly what they were doing. They immediately arrested me and Malcolm.” Reid spent a night in the cells, alongside various Liverpool fans who’d been arrested at the FA cup final. “They were all singing ‘God Save the Queen’!”

That record, and Reid’s artwork, divided the country like no record before or since. “I had my leg broken,” he reveals. He was walking down Borough High Street, wearing a “God Save the Queen” T-shirt, when a gang of lads attacked him. “They put my leg over the kerb and jumped on it.”

And there were more subtle headaches to contend with. The Pistols’ records were censored, and so was Reid’s artwork. Was the establishment running scared? “I think they were really worried,” concurs Reid. Forty years since the Pistols split, his admiration for McLaren remains undiminished. “Malcolm was a genius, a complete genius – it was amazing what he did,” says Reid. “Take that idea of demanding the impossible – he was making the impossible a reality.” One thing that’s become lost in the mists of time is how much fun – and how funny – the whole thing was. “There was a lot of humour with the Pistols.” And a lot of humour in his Pistols artwork, too.

Punk was an important time in Reid’s life, but it was only a short time. “I’m not interested in fashion or music, as such,” he says. His interests are far more eclectic, ranging from Native American and indigenous art to the romantic poets and Thomas Paine. He’s an activist, not just an artist, as his track record since the Pistols confirms. He’s campaigned against countless injustices, from the poll tax to Section 28. And although he helped win both those battles, he believes that generally, across the country, things are now far worse than before. “You wouldn’t believe the poverty that’s going on in this country now. Desperate, desperate, desperate times. The whole concept of food banks, it’s just f**king unbelievable – a place like this having to give away free lunches because kids aren’t eating during the summer holidays!”

As you’d imagine, he’s no fan of Trump (“the man’s a monster, and proud of it”) and he’s a fierce opponent of imperialism (“What we did in the name of the British empire is just outrageous”) but he’s not a knee-jerk leftie. Above all, he’s interested in new ideas. He’s worked with KLF, the band who became (in)famous for burning a million quid. “They understood what we were doing, and moved it into a different age.” He hooked up with Pussy Riot, inviting them over to the Florrie. “They loved it here,” he says. “They found it so refreshing being here.” It was refreshing for Reid as well. For the man who created the punk aesthetic, it felt like coming full circle.

“I’ve been writing a lot about racism and nationality,” he tells me. “You know who the Scots are, you know who the Irish are, you know who the Welsh are, but who the fuck are the English? Who are they? Not Scousers, not Geordies… what most people conceive of as being English is just what they’re told – through their education, the bloody royal family, the history of the powerful. We’ve got a fantastic radical tradition in this country which is utterly ignored.” Reid is part of that tradition, and not only for his work with punk. If only there were a few more people like him, maybe places like the Florrie wouldn’t need to dole out free meals to local kids.

Back at Humber Street Gallery, his show is almost ready. A handwritten letter by Jamie, blown up huge, has pride of place on one wall. “Painting for me is everything,” reads his spiderlike scrawl. Across the room is a Sex Pistols montage, featuring artwork for “Pretty Vacant” and “Holidays in the Sun” and a bounced cheque (for £2,800) from Malcolm McLaren. “Media sickness – more contagious than Aids,” reads another slogan. There’s the dustjacket he designed for In the Fascist Bathroom by Greil Marcus. There’s the poster he made for Letter to Brezhnev, starring Margi Clarke.

Julien Temple has just arrived. He’s making a film about Jamie. If it’s half as good as The Filth and the Fury, his seminal documentary about the Sex Pistols, it should be well worth watching. I decide to leave them to it. In the street outside, someone has painted a slogan on a wheelbarrow, of all places: “A true artist is not one who is inspired, but one who inspires.” This isn’t one of Jamie’s slogans – it’s actually a quote from Salvador Dali – but more than any of his own slogans, it seems to sum him up.

Jamie Reid XXXXX: 50 Years of Subversion and the Spirit is at Humber Street Gallery, Hull, until 6 January 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks