An Israeli-Palestinian settlement is possible – but not unless the international community wills it

Many bear responsibility for the longstanding failure to conclude a peace deal, including Britain. And, as Donald Macintyre explains, the Palestinians cannot be expected to go on waiting forever

The World Bank’s most recent report on Gaza says its economy is in “free fall”; the conflicts at the border are heating up again, with seven Palestinians – including two children – killed by Israeli forces in a particularly violent day at the end of September. There is even talk about the possibility of another major military confrontation between Israel and Hamas.

During his distinguished career with The Independent Donald Macintyre was the paper’s Jerusalem correspondent for eight years. In the following extract from his book on Gaza, out in paperback next week, Donald traces the factors – including international neglect – that have driven the impoverished and besieged Gaza Strip to this point.

***

On a chilly, grey Sunday afternoon in January 2003, we were standing outside what had been, until the night before, Mahmoud al-Bahtiti’s vehicle engine repair shop in the southern Gaza City neighbourhood of Zeitoun. The previous night, Israeli tanks, supported by Apache attack helicopters, had rumbled along the main north-south Saladin road, ramming three buses – which still lay mangled and skewed across the road – setting market stalls on fire and flattening three houses identified by Israeli intelligence as belonging to the families of Palestinians who had launched attacks across the border.

Eleven of the 12 Palestinians killed that night were militants who had rushed onto the streets to fire their AK-47s on heavily armoured Israeli troops. The incursion, which followed the firing of 10 homemade Qassam rockets into Israel, albeit without causing injuries, had ended before dawn. As the 50-year-old al-Bahtiti nodded towards the smoking ruins of his metal workshop, one of more than a dozen destroyed overnight, he shrugged and a brief grin flitted across his face. “So Abu Ammar said Gaza was going to be the new Singapore,” he said.

The sardonic – and characteristically Gazan – joke was a reference to Yasser Arafat’s portentous prediction nine years earlier of a Gazan renaissance, and it summed up how the expectations raised by the PLO leader’s triumphant return to Gaza from Tunis in 1994 had gone the way of al-Bahtiti’s workshop. That day in January 2003 the Israeli military said it had destroyed 100 lathes that had been or could be in the future used to make rockets. Al-Bahtiti insisted he had never made a single rocket; his premises had been used only to fix car engines. Either way, Gaza was not morphing into Singapore any time soon. What al-Bathiti could not begin to imagine was the far worse destruction, economic as well as military, that would be inflicted on Gaza over the next decade and a half.

They do it just for revenge. To destroy the economy of course. They use building rockets as an excuse to destroy the economy

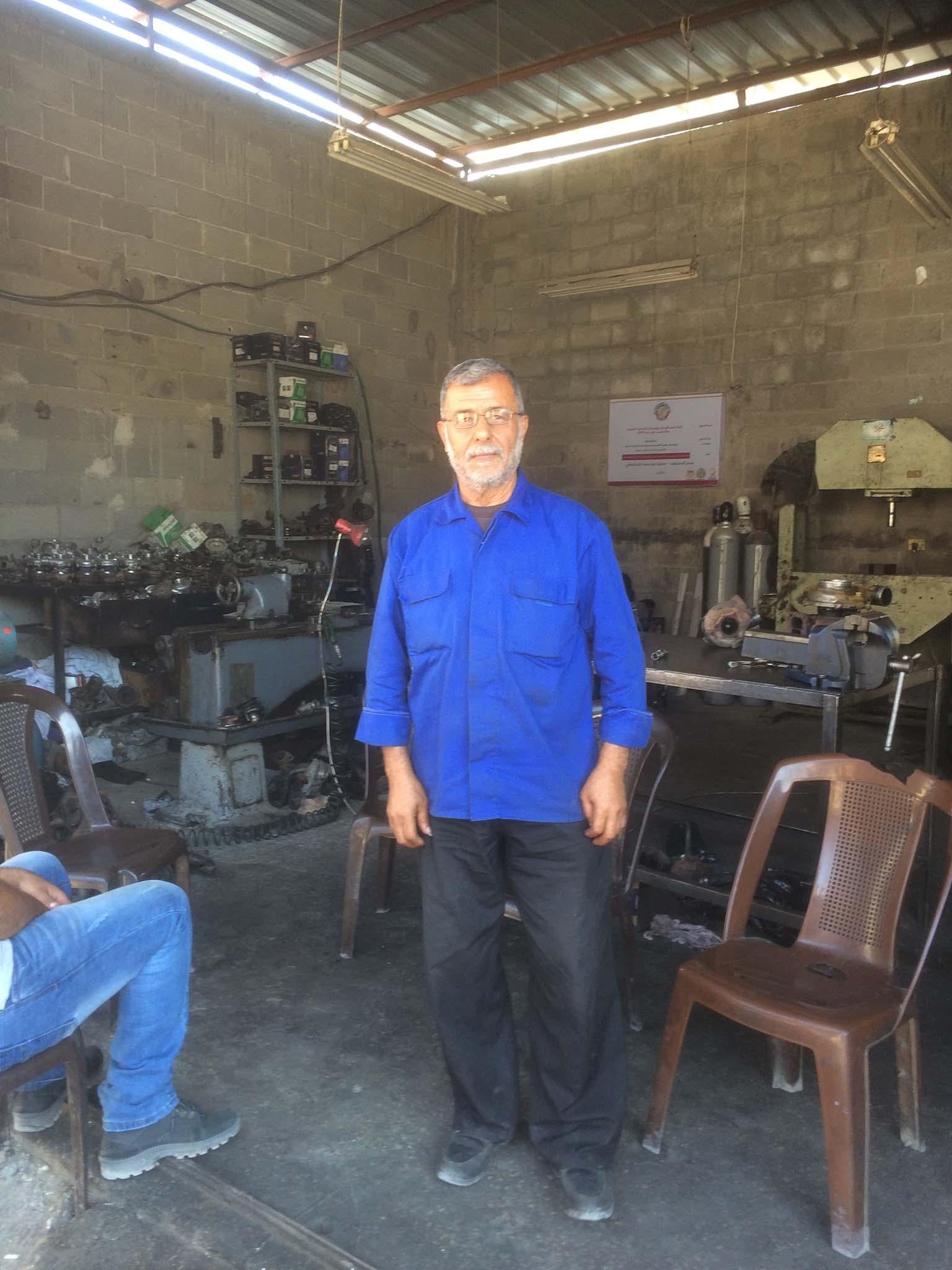

Al-Bahtiti was the first Palestinian I ever met in Gaza. Almost 14 years later I went back to Zeitoun to find him. It came as a surprise to discover that this wiry figure, looking younger than his 66 years with a neatly trimmed beard, blue open-neck shirt and the same dry sense of humour, was still in Al Basateen Street and still fixing car and truck engines, as he had been doing for half a century.

But, he said, business had never been slower. He had stopped complaining about the Hamas government because of the shortage of electricity; thanks to the scarcity of work, the interruptions hardly mattered anymore. “They can cut it as much as they like,” he said. “Gaza is like heaven. There is no work in heaven either.”

Al-Bahtiti had first learned his trade when he left school at 15, two years before the Six Day War, and started out on his own five years later. Those were the years of open borders when it was almost as easy for Palestinians to travel out of the Strip as it was for Israelis to travel in to buy fresh fish – or have their engine cylinders, camshafts and turbo-chargers fixed a good deal more cheaply than in Israel, and just as reliably. In al-Bahtiti’s words: “I am not praising Israel, I am just saying that it was a fair life back then.”

Business had been all right during the Arafat years after Oslo, he said, but it had got gradually worse and worse. As it happened, he had suffered exceptionally bad luck; his workshop had been destroyed or badly damaged not just in 2003 but in each of the three wars since then. In 2012 he had moved to Tel el Hawa where his premises were collaterally damaged in a strike on a nearby office of the Ministry of Interior. “They never forget me,” he said wryly. Did the Israelis think he still made rockets? “No, they do it just for revenge. To destroy the economy of course. They use building rockets as an excuse to destroy the economy.”

Al-Bahtiti still stood by his gibe at Arafat from that cold afternoon in January 2003. But after the three wars and nine years of economic siege that followed Hamas’s takeover of Gaza, he thought maybe he had judged the Palestinian Authority established by Arafat too harshly. After the elections, he said, “Hamas was not only rejected, but also hated, by most of the governments in the world. Subsequently, the Palestinian people in Gaza were treated in the same way Hamas was treated. We’re all prisoners in Gaza, not only because of Israel, but Egypt and Jordan as well.” Al-Bahtiti reached back to the lines of a song from his teenage years by the greatest of all 20th century Egyptian singers, Umm Kulthum: “Give me again my freedom, and let go my hands.”

Then he asked me a question. Given that Britain had issued the Balfour Declaration a century ago and “we are still suffering as a result of that declaration”, wouldn’t an apology from the British government be in order? No, he wasn’t trying to get what was now Israel back for the Arabs. He recognised that “the Jewish people took their rights after Hitler committed massacres against them. But who will give us our rights? Germany still supports Israel till now, but Britain gave our lands to the Israelis and they never cared to give us our rights.”

Agree with him or not, al-Bahtiti touched a raw nerve. He was not wrong to trace the Palestinian experience back to the events of 20th century history, culminating in the genocide of European Jews in the Holocaust. Nor was al-Bahtiti wrong to internationalise the problem by implying that other countries as well as Israel bore a responsibility for solving it, very much including the British who occupied Palestine, and then abandoned it to a conflict that remains unresolved 70 years later. It is not a responsibility those countries have exercised with distinction over the past decade.

During a thoughtful speech in Monterey less than a year before the US-British invasion of Iraq, the then US deputy defence secretary Paul Wolfowitz suggested: “To win the war against terrorism and, in so doing, help shape a more peaceful world, we must speak to the hundreds of millions of moderate and tolerant people in the Muslim world, regardless of where they live, who aspire to enjoy the blessings of freedom and democracy and free enterprise. These are sometimes described as “western values”, but, in fact, they are universal.”

To win the war against terrorism and, in so doing, help shape a more peaceful world, we must speak to the hundreds of millions of moderate and tolerant people in the Muslim world, regardless of where they live, who aspire to enjoy the blessings of freedom and democracy and free enterprise. These are sometimes described as ‘western values’, but, in fact, they are universal

It is striking that “the blessings” identified in that unimpeachable doctrine were precisely those denied to Palestinians in Gaza. The international boycott imposed after the 2006 election result was hardly a ringing endorsement of democracy. The prolonged blockade, ostensibly aimed at Hamas for refusing to comply with the conditions laid down by Israel and the Quartet, afflicted the civilian population far more than Hamas itself. Despite protestations to the contrary, this made it all the harder for Israel to escape the charge that it was collectively punishing Palestinians in Gaza for their electoral choice, however varied their reasons for making it and however lacking in opportunities they were for reversing it.

In Gaza it was a classic case, in Sara Roy’s memorable description, of sanctions being applied against the occupied rather than the occupier. But it was also a reminder that for 50 years Palestinians have had no say in choosing the government that ultimately controls their lives, whether by having a state of their own or by being given the vote in a single, binational state.

The freedom of Gazans to travel, as well as to import and export goods, had been curtailed long before Hamas’s election victory, of course. But it had been much more tightly restricted over the past decade than at any time since the Six Day War. When the British carried out their ferocious bombardment of Ottoman-controlled Gaza City in 1917, those fleeing were at least able to get to other parts of Palestine. That possibility was not open to the vast majority of Palestinian civilians facing the three military onslaughts of 2008-9, 2012 and 2014. All of which helps to explain why, according to the Israeli human rights agency B’Tselem, 2,237 of the Palestinians killed in all three wars were non-combatants.

But it was the crushing of “free enterprise” that was perhaps the most striking consequence of an economic blockade of Gaza, which the Quartet approach helped to legitimise. The creation of a 300-metre (at least) buffer zone and the imposition of a three- or six-mile limit in Gaza waters wrought a devastating effect on both agriculture and the fishing industries. It is difficult to see how the collapse, mothballing, or – in wartime – outright destruction of hundreds of manufacturing companies, many owned by people with no love for Hamas and who had enjoyed close relationships with Israeli customers and suppliers, helped Israeli security. Let alone the consequential drift of the unemployed into jobs with Hamas, including its armed and paramilitary wings, as well as those hired to dig tunnels that were seen as a security threat to Israel. What was eliminated, in an instinctively entrepreneurial society, was an economy which had in living memory provided not only incomes but a measure of human dignity.

The point is underlined when older Palestinians talk, as al-Bahtiti did, about the “golden” time before Oslo for Gazan businesses and workers. On the face of it, there was not much golden for Gaza between 1967 and 1993. It was an era often characterised by roundups, arrests, bulldozing of homes and citrus groves, lethal firefights, the seizure of land and water for Israeli settlements, the army’s house-to-house sweeps of the refugee camps, and all the other pressures which accompanied the constant physical presence on the streets of a military occupation. But al-Bahtiti’s nostalgia for the period when Israel was directly running Gaza powerfully illustrates how far conditions, especially economic, have deteriorated since then.

Israel placed severe limits on the Gazan economy in those first two and half decades of occupation, making it wholly dependent on theirs. But then defence minister Moshe Dayan’s strategy after 1967, partly in order to subdue Palestinian nationalist sentiment, was to allow many tens of thousands of Gazans to work in Israel, and for businesses to trade with it. From the early 1990s this relative openness was gradually replaced by a policy of separation, culminating in a 21st century blockade, which left Gaza with virtually no economy at all. Finally the de-development was completed by three military assaults on the Strip within six years which failed to dislodge Hamas but had a devastating impact on the civilian population. Without a major rethink of Israeli and international policy, the assaults could well be repeated.

It was too easy to blame Israel alone – as al-Bahtiti recognised. If Gaza was an open prison, Israel was not the only gaoler. Gazan Palestinians had also been forsaken by Egypt – especially by President Sisi’s prolonged closures of Rafah and the destruction of the smuggling tunnels – and Jordan, through the strict transit restrictions it imposes on Gazan (but not on West Bank) residents. They had been betrayed by the chronic failure of Fatah and Hamas to resolve their differences, subordinating the interests of Gaza’s public to their own in a conflict made especially disheartening because the power they were struggling for was so heavily circumscribed by Israel. And, perhaps least discussed of all, they had been abandoned by the international community and western governments in particular.

The Middle East “Quartet”, which in practice meant the US and the EU, could say that it had frequently called for the easing of the blockade. So it had; and after the Mavi Marmara episode in 2010, in which Israeli commandos killed nine people aboard the Turkish Gaza-bound aid ship, it persuaded the Netanyahu government to allow in a much wider range of consumer goods. But this did nothing to revive Gazan industry because exports were still banned. Nor was there any lifting of the restrictions that closed off Gazan residents’ access to the outside world. In fact, there was no sign of either the EU or the US applying serious leverage on Israel to end the isolation of the Strip.

In practice, Gaza seemed to share with North Korea – before Donald Trump’s uneasy courtship of the latter – the status of a territory where the civilian population was suffering but nothing, beyond providing the humanitarian minimum, could be achieved as long as a pariah government was in charge.

Yet that pariah status was itself conferred by Israel’s and her western allies’ boycott of Hamas after it won free elections in 2006. The international denial of contacts and funding then persisted for more than a decade despite an increasing realisation, at least among some of the Europeans who had originally decided on it, that it had been a mistake.

The question for the international community that resounded after 10 years in which most of civilian Gaza lived in fear, poverty and despair while its rulers’ political and military control remained intact, was not so much “why talk to Hamas” as “why not”? Maybe Hamas’s previous oscillation between violent insurgency and the exercise of political power makes it hard to assess with certainty what the outcome of engagement would have been. But for the Quartet to have set more realistic conditions – for example, a long-term truce with Israel – would not have precluded the imposition of sanctions if Hamas had violated them; indeed, it would have afforded western governments the leverage over Hamas’s conduct that it now conspicuously lacked. Exactly what had been the gains to Israeli, Palestinian, regional and global security from this policy? And why was it not re-thought in the light of Hamas’s first official and public espousal of a Palestinian state on 1967 borders in May 2017?

But, of course, the plight of Gaza cannot be separated from that of the wider Israeli-Palestinian conflict. First, there can be no lasting end to that conflict, let alone the creation of a Palestinian state, without Gaza. Gaza, with its 2 million Palestinians and its economically all-important coastline has to be a part of it.

It’s also worth reflecting that Hamas, now running Gaza, did not come from nowhere. Back in 1995, fearing the unravelling of the Oslo accords, Haidar Abdel Shafi, the most revered of all Gazans, remarked that Hamas would not dare to disrupt a “credible peace process”. Abdel Shafi was underlining that Hamas’s strength – beyond the bedrock of its minority support – had risen in direct relation to the failures of serial peace negotiations with the PLO. It would be rash to presume that Israel and the west can now indefinitely postpone a “credible” peace process without in turn strengthening the more extreme forces – whether looking towards Isis or not – which Hamas has so far contained in Gaza.

The Americans were seen as biased in support of Israel... [and the] moderate Arabs who want to be with us… can’t come out publicly in support of people who don’t show respect for the Arab Palestinians

One of the most pervasive – and baseless – myths about the conflict is that a peace process can only work if the two parties want it, and that no external force can bring them together if they don’t. The opposite is the truth. An end to conflict will simply not happen unless the outside world not only demands it but puts irresistible pressure on the parties, and in practice that means the strongest party and the one that believes it has the greatest interest in maintaining the status quo, namely Israel, to reach an agreement. There are few grounds for optimism that, eager as he is for the “deal of the century”, President Trump is ready to pursue that course. His move of the US embassy to Jerusalem and his remarkable boast that he has taken the city – a core issue in previous negotiations – “off the table”; his cuts in funding to the UN Palestinian refugee agency UNRWA, which suggests he may be hoping also to take the refugee issue “off the table”; and his dependence on a fiercely pro-Israel right-wing Christian evangelical constituency, are hardly grounds for confidence that he is planning a deal which would meet even minimal Palestinian demands.

After the liberation of Kuwait from Iraq by the US-led coalition in 1991, George Bush dragged a deeply resistant Yitzhak Shamir to the Madrid summit by suspending the US’s multibillion-dollar loan guarantees to Israel. The ensuing process did not, finally, succeed; but it was a now all too rare indication of the traction open to a determined US administration. “The United States could stop [the settlements] so easily,” the liberal Israeli novelist AB Yehoshua told me in Haifa in 2005. “Since the Six Day War they were saying they were against the settlements, and they have done nothing.”

The US interest in subsidising Israel by more than $3bn a year without exacting conditions is questionable, to put it mildly. No one sane thinks that the current global terrorist threats facing the west – like that posed by Isis – were generated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But in 2013 a former US general remarked that he “paid a military price every day” when he was in charge of US Central Command “because the Americans were seen as biased in support of Israel” and that the “moderate Arabs who want to be with us… can’t come out publicly in support of people who don’t show respect for the Arab Palestinians.” This was James Mattis, appointed by Trump as defence secretary in 2017.

This is not the place to spell out the historic reasons for that “bias”, including the influence, exercised through its funding of US political campaigns, of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. But AIPAC has always been more representative of successive Israeli governments than it has of American Jewry. Indeed, one prospect of change in the longer term lies with indications both of a gradual fraying of bipartisan support for “Israel right or wrong” among US Democrats, whom most American Jews support, and of a markedly more critical attitude towards present-day Israeli government policy among some younger American Jews.

But Mahmoud al-Bahtiti was also right to focus on the Europeans. For the EU has stolidly continued to channel aid – at least €6bn since 1994 – to the Palestinian authority to ameliorate the impact, in the West Bank at least, of a policy with which it says it disagrees but over which it has made no attempt to exercise any real influence. The EU’s effective subsidy of the occupation by ensuring the PA’s obligations under Oslo, for example, to provide healthcare and education are met, however imperfectly, gave it a duty as well as a right to exercise some leverage in the conflict beyond pious restatements of its belief in a two-state solution.

$30bn

The total trade done between Israel and the EU each year

One of the major, possibly the major obstacle to an international plan for rehabilitation of Gaza’s infrastructure, has been the insistence of Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas that this should not happen before Hamas first agrees to his terms for reconciling the two factions (Hamas and Fatah), including putting its armed security services under his control. Politically Abbas, who has also now borne down on Gaza’s economy with draconian sanctions of his own, may have a case; but, as usual, the main victims are not Hamas but Gaza’s 2 million inhabitants. The EU has the capacity to bring pressure on Abbas to devise another approach but not the will; in relation to Hamas it does not even have the capacity, thanks to its 11-year boycott of the Islamic faction.

But the EU also has leverage on Israel; it is Israel’s biggest trading partner, accounting for a third of the latter’s foreign trade, worth around $30bn, covered by free trade agreements which exempted Israeli exports to Europe from tariffs. Yet without even re-erecting such barriers, let alone boycotting Israel, the EU could make a sharp impact by differentiating – robustly – between Israel proper and Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, regarded by the EU as illegal in international law, including by a ban on imports of goods from the settlements and secondarily on banks and others doing business with Israeli companies operating in the occupied territories.

Britain, whether it still sees itself as European or not, has an especial historic responsibility, both because of the 101-year-old Balfour Declaration and its abandonment of Palestine to the warring parties in 1948. More than a century after Balfour, Britain has amply fulfilled its first commitment to “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”, but wholly failed to live up to the second – ensuring that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”.

To keep – finally – the Balfour Declaration’s broken promise would be vastly more difficult were a just end to conflict not in Israel’s interests as well as that of the Palestinians. The more extreme champions of the Israeli and Palestinian causes like to claim this is a zero sum game, in which every gain for the Palestinians is a loss for Israel, and vice versa. But it isn’t. Since 2002 the Arab League has offered Israel full recognition, with all the accompanying benefits, including economic, that would entail, in return for a peace agreement with the Palestinians based on an end to the occupation it began 50 years ago. Israel, for the first time since 1967, would have internationally recognised borders. The major Sunni Arab states were eager for such an agreement because they believed that, with nuclear-armed Israel as an ally, they could together form what they see as a necessary counterweight to Iranian power in the region.

It’s true that Netanyahu now believes, with some reason, that he has already secured an informal strategic regional alliance without reaching a fair agreement with the Palestinians. For the Saudi government and its allies thwarting Iran is a higher priority than a just peace for the Palestinians. Nevertheless they are unlikely to try and force the Palestinians to accept a “deal of the century” they don’t want. And even if they did, it would not douse the flame of Palestinian nationalism and the quest for independence and freedom.

And a positive outcome to that quest itself remains – contrary to what the Netanyahu government believes – an Israeli as well as a Palestinian interest. A resolution would bring an end to the morally corrosive effects of the occupation on Israeli society, including on the young soldiers obliged to enforce it, and by resolving the patent injustice of denying Palestinians civil and political rights. It would address the increasing hostility to Israel that the occupation breeds abroad. And the dilemma highlighted by successive leaders from Ehud Barak to Ehud Olmert is inescapable: either it grants Palestinian independence on terms that a Palestinian leader can – literally as well as politically – live with; or it casts itself as an apartheid state, facing increasing demands by Palestinians for equal human and political rights in a single state which would mean the end of Israel as it is now.

As long as it prefers to “manage” the status quo – ie subjugation of the Palestinians – it’s hard to resist the conclusion that in the long term the greatest existential threat to Israel is not Iran or Isis, let alone Hamas, but Israel itself.

If a peace agreement is not concluded, then after 50 years the Palestinians cannot simply be told to go on waiting for relief until some mythical future when it will be. And that means applying genuine pressure on Israel to grant them some of the rights – economic rights to begin with, though that will never be enough without political rights – that they have so long been denied. This applies to all Palestinians, but Gaza, facing the direst conditions of all, is the right place to start; whether or not Israel or the PA agree. No doubt aid needs to be more equitably shared between Gaza and the West Bank, and it is difficult to see how it can be truly effective in the absence of international engagement with Hamas. But in the longer term what Gaza has always wanted and needed is not aid but an economy; the recovery of its capacity to make, cultivate and trade.

A new seaport for Gaza, which could attract substantial private sector investment, is only one instance. It would not only at least begin restoring the territory as a trading hub again, and provide hundreds if not thousands of jobs while it was being built, but in the words of one of Israel’s more hard-headed securocrats, ensure that “during that process Hamas would have a good incentive not to open fire on Israel, which would risk this international project”. The seaport is a good example because part of the reason it has so far been rejected – despite some support even within the Israeli Cabinet – is that it was one of Hamas’s demands at the end of the 2014 war. A rethought international policy towards Gaza needs to abandon, in the interests of its people, the childish notion that nothing must be done for which Hamas could conceivably claim some credit.

2,500

The number of Palestinians estimated to have been injured in protests at the Gaza border this spring. 120 were killed

The alternative to such a rethink could well be another war or wars. All too often the talk in Gaza and Israel has turned towards the prospect of armed conflict and not only for the sake of military advantage. The two most calamitous wars had both been linked to the siege; the rocket fire that Israel cited as the reason for its assault in 2008 could have been prevented if the siege had been lifted. And in 2014 Hamas, backed into a corner by the failure of its agreement with Fatah, its political isolation after Morsi’s fall in Egypt, the arrests of its activists in the West Bank after the murder of three Israeli teenagers, the killing of seven of its Gaza militants and above all the dire conditions in the Strip, opted for a war, that as expert Nathan Thrall put it, “had a chance, however slim, of loosening the squeeze”. On most counts the economic and humanitarian conditions in Gaza are now much worse than those which formed the background to the 2014 war.

So the siege was the key factor when Gaza did erupt on 30 March 2018, albeit in a wholly unexpected way: the first unarmed mass protests in the Strip since the First Intifada. Tens of thousands of Gazans – often entire families – gathered near the border while hundreds more, mainly young men, some throwing stones, Molotov cocktails and launching flaming kites, advanced on the border fence, coming under live Israeli sniper fire from the other side. At least 120 Palestinians were killed, 62 of them on the climactic day of the weekly protests, 14 May, just as Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump were inaugurating the new US embassy in Jerusalem, transferred from Tel Aviv in defiance of long-standing international consensus and the Palestinians’ dream of a shared capital in that binational city.

On the Gaza side of the border you could see the white plumes of teargas against the thick black smoke of burning tyres, and hear above the screaming sirens of ambulances, their red lights flashing, the cracks of sporadic gunfire. But 50 miles away at the Jerusalem ceremony, an exultant Netanyahu, seemingly oblivious to the mounting toll of deaths, the highest on a single day since the 2014 war, or of injuries to over 2,500 Palestinians (and one Israeli soldier), celebrated the embassy move on “a great day for peace”.

Although it did not originate the protests – they were the idea of some local Palestinian graduate students – Hamas subsequently organised them; from policing and the provision of field hospitals, to the demagogues urging the young men towards the fence from the tents strung along the border. Some of those killed and injured were its own activists. But many others were not, and it is inconceivable that the protest – also backed by Fatah in a rare display of unity – would have attracted such numbers were it not for Gaza’s dire conditions. It was called “the Great March of Return”, an assertion of the “right to return” of over 700,000 refugees displaced by the 1948 war which established the Jewish state, to their ancestral homes in what was now Israel. This theme was as alarming to Israelis as it was unifying in Gaza, where well over half the population were refugees.

But that neatly mirrored Israel’s unbending Israeli insistence on Jerusalem as an “undivided and eternal” capital. It reflected the failure over three decades to reach the two-state deal for which most Palestinians had long hoped and which would have included an honourable compromise on Jerusalem and refugees. If Jerusalem was “off the table”, the Palestinians might argue, so too would be a compromise on refugees. In repeated interviews the jobless young men – “hopeless people with nothing to lose” as the Fatah-supporting Gaza writer Atef Abu Saif put it – routinely echoed the “return” mantra. But it became swiftly clear that what they wanted most was “to make our dreams come true, find a job and have the crossings open”, in the words of Mahmoud Mansour, 23, his elbow bandaged from an injury during a previous protest.

What was much more doubtful was whether the international outcry over the shootings, echoing that during the 2014 war would help to ensure that dream would indeed come true. It was hard to think of a better way of preventing, at least in the medium term, a further escalation. For another war cannot be ruled out. The deaths in the spring of this year triggered criticism from a minority of Israelis appalled that live fire, rather than less lethal crowd control methods, had been used against the protesters. But the relative ease with which many, perhaps most, Israelis accepted the deaths as inevitable matched the majority – 90 per cent in one poll – support for 2014’s Operation Protective Edge.

True, mainstream Israeli media coverage, with the notable exception of Haaretz, one of the world’s best newspapers, was highly supportive in the 2014 war. The revelation of the Hamas tunnels constructed under the border no doubt helped to sustain the war fever. But was the closure of Gaza itself a factor? Apart from soldiers in combat, most Israelis knew little of Gaza from the inside. Even those kind Israelis (and there were quite a few) who volunteered to drive to Erez to ferry sick Palestinians to hospitals in Jerusalem or Tel Aviv inevitably had little idea what lay on the inside.

In her fine book about living in the Strip in the 1990s, the Israeli journalist Amira Hass wrote “the Israeli point of view is best summed up by the local variant of ‘go to hell’ which is quite simply ‘go to Gaza’”. Yet even since then there had been an 11-year ban, ostensibly on security grounds, by the Israeli government on Israeli journalists reporting from inside the Strip, as many – Hass and her Haaretz colleague Gideon Levy among them – used to do with distinction. It made Gaza seem even more unfathomable and dangerous to its neighbour than it once had. It was tempting to wonder if the story of Samson, his deception and capture in Gaza at the hands of the Philistines and his final destructive act, had re-emerged from the depths of Israel’s collective subconscious; a biblical allegory to be played out again and again.

Certainly the right-wing Israeli commentators who blithely describe wars in Gaza as “mowing the grass” depict them as a routine event, necessarily repeated every few years. When in Milton’s Samson Agonistes the messenger arrives with the news that Samson – in perhaps the world’s first recorded suicide attack – has killed the elite of Philistine society by pulling down the temple of Dagon, the chorus glorifies him for dying “conjoined… with thy slaughter’d foes in number more/Than all thy life had slain before”. Such an epitaph may be bleakly accurate for IDF soldiers sent into Gaza and unlucky enough not to come out alive. But is it really one that Israel intended to keep writing for its young conscripts by regularly sending them to “mow the grass”?

War in Gaza is avoidable. There have been several public warnings from within the Israeli military that deteriorating humanitarian conditions in Gaza could “blow up” at any time, and those arguments were made even more forcefully to Israel’s political leadership in private. And the obverse was that radical improvement in those conditions was the best means of preventing such an explosion.

Gaza may not yet become Singapore, or want to. But it still has the talent, education, resources and geography to recover over time. If the international community, with or without the US, were to use the capacity it undoubtedly has to influence events, it could start by reaching for the one outcome for Gaza that hasn’t been attempted: lifting the siege and restoring a measure of enterprise, liberty and respect for democracy to its beleaguered and imprisoned people. As Umm Kultham sang, “Give me again my freedom and let go my hands”.

This essay was adapted from ‘Gaza: Preparing for Dawn’ (paperback published by Oneworld on 7 October 2018).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks