How millennials are breathing fresh life into the ancient Irish language

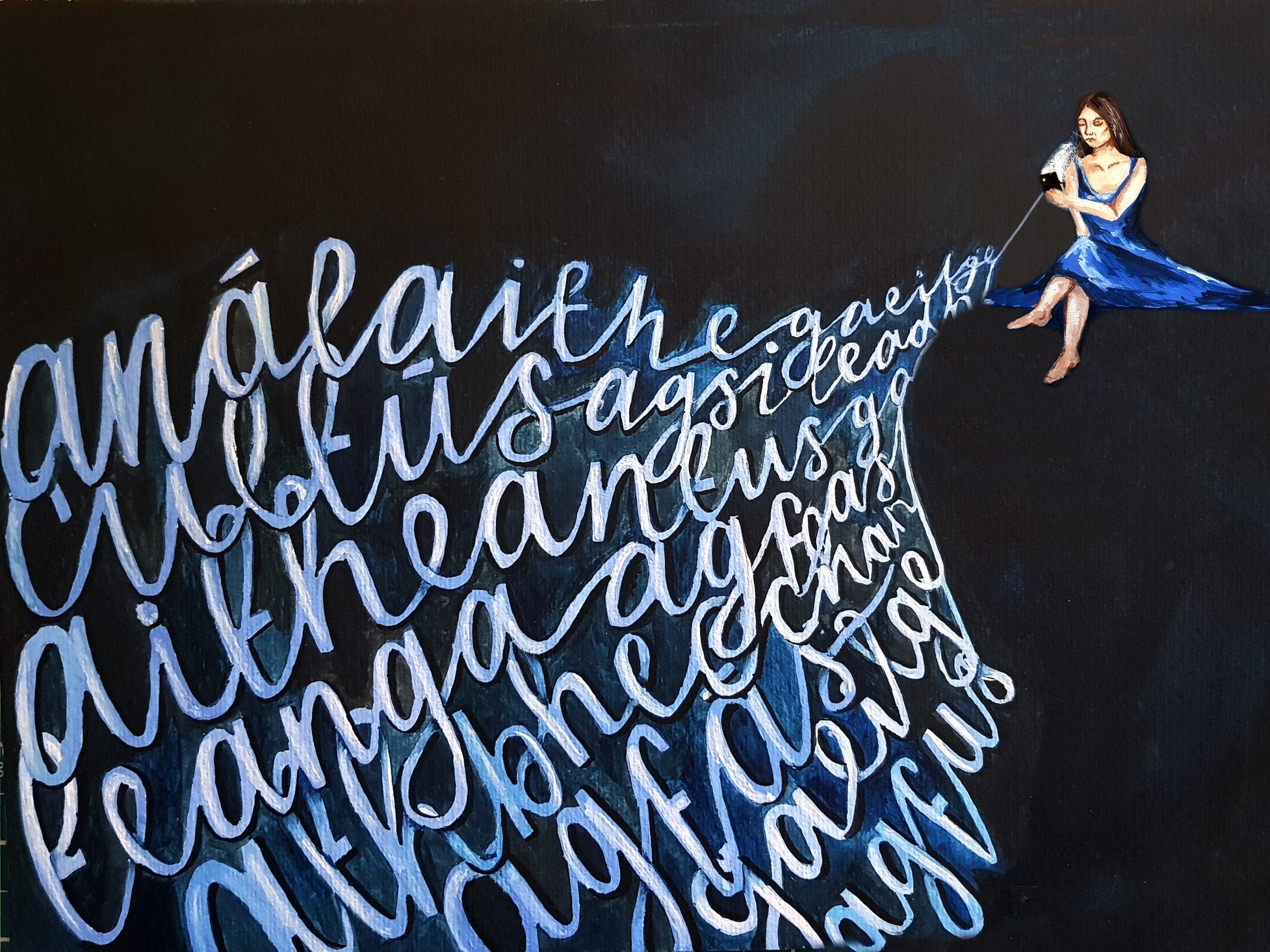

New generations of Irish people are engaged in a very 21st century revival of their native tongue – Ben Kelly discovers how Gaelic is being dragged out of the classroom and into the outside world

Irish is making a comeback. “This might sound dumb,” wrote Twitter user @dalteparin in August 2018, “but...what if we all just start saying simple phrases like ‘go raibh maith agat’ [thank you] to each other every day to normalise speaking irish and slowly reintegrate her into our day-to-day lives.”

The tweet struck a chord, and quickly went viral. Within days, it appeared across Facebook and Instagram too. It tapped into something fairly unique about the native language of Ireland; while millions around the globe feel a patriotic responsibility towards its survival, most of us are guilty of its neglect.

Irish (Gaelic) enjoys a rich history, with texts dating back to the fifth century. It is believed that as late as 1800, it was still the main language for a majority of people on the island. It suffered a slow demise across centuries of British colonial rule, where it was stamped out through the changing of place names, discrimination and prejudice against speakers, and the promotion of English in public life. When the Great Famine of the 1850s saw millions starved and forced to emigrate, the number of speakers plummeted further.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Gaelic revival saw nationalists attempt to assert their political independence by reviving the language through classes and cultural endeavours, but usage continued to decline.

After partition in the 1920s, Irish became the official language of the Republic of Ireland, but attempts to revive the mother tongue to its former glory have always struggled. Today, around 40 per cent of people can speak the language in the Republic of Ireland, but less than 2 per cent say they use it daily outside the education system. In Northern Ireland, around 6 per cent of people can speak the language, but just 0.2 per cent use it as their main language at home.

Traditionally, speakers were to be found in the Gaeltacht regions on Ireland’s west coast, where generations of teenagers are sent to boost their learning in the summer weeks. But now, you might also find them in a distinctly more modern forum. Take a nosey around Irish Twitter, and amid Brexit memes, adoration for President Higgins’ dogs and laments about the cost of Dublin rent, you’ll find it: the Irish language, and the effects of a very 21st-century revival.

Someone who has been at the helm of this is Dubliner Darach Ó Séaghdha. In 2015, after the death of his father – a lifelong Irish enthusiast – he got back into learning the language himself. “I started realising how wonderful it was when there was no school curriculum attached,” he says. “Then I just started documenting it on Twitter. I thought someone else might get something out of it.”

And they did. The ensuing Twitter account @theirishfor quickly picked up a big following online, with its entertaining approach to language learning having now garnered almost 40,000 followers.

A classic from January 2016 reads, “The Irish word for the sea is ‘farraige’ – not to be confused with ‘farage’, which means something that should get back in the sea.”

It has become something of a digital water cooler for those with even a passing interest in all things Irish – most of them from the much discussed millennial generation. “Most of my followers would be younger than me, people in their 20s and 30s. I think part of it is more than just the Irish language, it’s because Irish people use social media in a particular way – they have their own sense of humour.”

The success of the account sparked a book and a podcast, both called Motherfoclóir, and a follow-up, Craic Baby. The podcast is like a gathering of friends, who take an Irish word or a concept and use it as a entry point into a lively, irreverent group discussion.

“Some people might think it’s odd to have an English language podcast about the Irish language, but I think it’s important to have a bilingual hinterland where people can gradually dip into that.”

While the majority of people downloading the podcast are from Ireland, a growing number are tuning in from the UK and the US.

“I do think that social media has been a big way for the diaspora to stay connected, and that’s really been the case in the two recent referendums, with the Home To Vote movement. Before when people left, they left for good. But now when Irish people go abroad, they very much stay in touch with Irish events and keep their oar in, in a way they didn’t before.”

Another online forum helping people engage with the language from abroad is Duolingo. The app was founded in 2011, and currently allows users to study 33 different languages, including Irish.

In a statement, the company said that it was inspired to start working on that particular course after an Irish teenager wrote a letter to it stressing the importance of preserving the language, and making a strong case for it being offered on the service.

Today, there are about one million active learners of Irish on the app, with four million people having given it a go. Over four in 10 (42 per cent) of users are in the US, 22 per cent in Ireland and 10 per cent in the UK. These are considerable numbers when placed in the context of native speakers, and Ireland’s population.

Talk the talk

Five Irish phrases for beginners

Dia duit (jee-a-ditch) – Hello

Go raibh maith agat (gu-row-my-ugat) – Thank you

Cad é mar tá tú? (cad-yay-mar-ta-tu) – How are you?

Fáilte (fal-cha) – Welcome

Slán (slan) – Goodbye

Undoubtedly, many of those signing up to learn from distant countries are Irish emigrants and their descendants, who feel a strong pull to the homeland. The company was even honoured by President Higgins – a fluent speaker himself – for its efforts to help preserve and spread the language around the world.

Now, as people in their teens, twenties and thirties reclaim Irish for themselves, many are also raising their children with the language – building a new generation of native speakers.

Éimear Uí Choinn is a 28-year-old primary school teacher in Derry who was raised only with English, but studied the Irish language at school and university. She and her husband Séanna – who was raised bilingual – are now doing the same with their two children, 7-year-old Eilís and 2-year-old Rossa.

“Eilís is very aware of her bilingualism and loves it,” she says. “She’s always saying how it’s great she has two ways to say things. Rossa obviously isn’t aware that he is bilingual, but swaps effortlessly from English with his childminder, to Irish with us.”

Eilís and Rossa attend a Gaelscoil, a school which teaches exclusively in the Irish language. Some children who attend will go on to a mainstream English school at secondary level, or continue in Irish all the way through their education.

“Some have asked if it will negatively affect their English but if anything, the opposite is true. I really think her bilingualism has given her a huge advantage, she’s almost finished the fourth Harry Potter book in Irish.”

“We know so many young couples raising their children through Irish. I think people are reviving the language as they’re seeing the social and emotional benefits of it and I think there is an element of reconnection with our culture, tradition and heritage.”

While this reestablishment of Irish tradition is important, fluency with the native tongue also provides practical benefits in life and employment. Familiarity with the language is valued across many public roles in Ireland, and while English and French may continue to dominate internationally, Irish can still earn its speakers a seat at some of the world’s top tables.

Seanán Ó Coistín works as a translator for the European Union in Luxembourg City. He learned the language at school in Kildare at the age of four. Now, at 37, he spends his days translating documents from English and French into Irish.

“Legally, it is very important that EU documents are translated into Irish because constitutionally it is the first official language of Ireland, and English is the second official language. If there is a dispute between versions of laws, the version in the Irish language prevails.”

Despite being an official EU language since 2007, Irish will not become a full working language of the institutions until 2022. This was highlighted by Sinn Féin MEP Liadh Ní Riada in 2015 when she went on a language strike, refusing to speak anything but her native Irish while doing her job.

Ó Coistín says the recognition of Irish as an official EU language helps strengthen Ireland’s position as a small nation in a large organisation.

“It means that teams of Irish speakers work inside the corridors of power in the EU. It is far more important that a country’s national language is used inside the EU buildings than having the national flag flying outside.

“Irish, as a small language, can win allies from speakers of other small languages, like Maltese and Estonian, which have fewer speakers than Irish. They know we face similar challenges.”

But while Irish is enjoying an elevation in Brussels, it’s a different story back home in Belfast, where it has become a crucial issue in the current political impasse. Northern Ireland’s power-sharing government at Stormont collapsed in January 2017 over a breakdown in the relationship between old political foes Sinn Féin and the DUP. While a mismanaged heating scheme was the straw that broke the camel’s back, the Irish language has become the main obstacle preventing the parties from returning to their elected roles. Unless an Irish language act is included in any new deal, Sinn Féin won’t return to share power – but the DUP refuse to concede any ground.

Sinn Féin point out that language rights were promised as part of the commitment to equality in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and use the language act in Wales as evidence that this is permissible in other parts of the UK.

But the DUP see the language as a weapon in the culture war which replaced the Troubles in Northern Ireland; a Trojan horse which will lead to Irishness overtaking Britishness in this part of the country – even though equality is all that Irish speakers seek.

And the DUP don’t simply discriminate against the language in legislation – they openly revile it. In 2014, MP Gregory Campbell sparked outrage by saying he would “treat as toilet paper” any proposal for an Irish language act, and mocked the phrase for “thank you” by saying “curry my yoghurt” in the Stormont assembly.

In February 2017, after Stormont collapsed, leader Arlene Foster set out her objection to the language act, saying, “If you feed a crocodile it will keep coming back and looking for more.” While Foster was undoubtedly playing to her base, it only enthused young language speakers – many of whom then protested against her while dressed as crocodiles.

While all of this may give the impression that the language is an orange and green issue, many unionists do not support the hard stance of Foster and the DUP.

Based in Belfast, Linda Ervine is a member of the largely Protestant unionist community. Having grown up knowing nothing of the language, she happened to take a taster class at the age of 49.

“I couldn’t have told you what the word ‘failte’ was,” she admits, referring to the Irish word for “welcome”. “I had no engagement before that. It looked strange, it sounded strange, but I just fell in love with it.”

As well as starting to learn the language, Ervine began researching, and reading books about it. She discovered – to her surprise – that it had a rich history among the Protestant community. “It was a real wakeup call to me.”

Now, across seven years of learning, she has become an unlikely language enthusiast and even teaches classes herself. She says people from all walks of life in Belfast are developing a curiosity for it.

“Last year we signed up 225 people for classes, and 70 per cent were from the unionist community. When we first started, people tended to be mostly middle-aged, but that’s changing, the demographic is starting to get younger. I’m teaching a class of parents and children, and they’re quite young parents with small children.”

Every word spoken in Gaelic is another brick in the bridge that unites us as people within these islands – whether that’s between Scotland and Ireland or Catholic and Protestant, because it is a shared language and a shared heritage

She feels that while bridges are being built at ground level through the language, politicians are exploiting the issue unfairly.

“I feel the language has been scapegoated. There’s been a lack of respect, a lack of trust and a lack of cooperation between Sinn Féin and the DUP. They seem unable to compromise. A language act should not be a big deal. It wasn’t a big deal in Scotland or Wales. We’re asking for the same rights as other British citizens.”

While the Irish language has often been more associated with Irish nationalism and republicanism, Ervine feels unionists have as much of a claim to it.

“The language is a link to other parts of these islands. It works for unionism. It actually works for unionism better than it does for republicanism. But it’s how you educate people. That’s not about saying it’s got to be compulsory and everyone has to learn it, but it’s about saying this language is not a threat.

“Every word spoken in Gaelic is another brick in the bridge that unites us as people within these islands – whether that’s between Scotland and Ireland or Catholic and Protestant, because it is a shared language and a shared heritage.”

For generations, the revival of the language has felt like a responsibility; a task incumbent upon all Irish people, to counteract its suppression over centuries of British rule. But too often, it felt like a chore.

Now, with more young people picking it up voluntarily, and in inspired new ways, it’s clearly being viewed in a fresh light.

There is an appreciation that a rich tradition is there for the taking; words, phrases and descriptions which are unique not just to our language, but to our landscape. It taps into national history, literature, mythology, and the very essence of who we are as people.

It is surely no coincidence that this current explosion of language pride is coming at a time when Ireland’s voice in Europe – and on the world stage – is getting louder.

And in spite of the stalemate in Northern Ireland, the language is proving its worth as a unifier – not just of people and traditions on the island, but in the diaspora around the world. Emigration scattered the Irish far and wide, but as our ancient language meets new technology, our bonds can only grow stronger.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks