In Iraq, the ghosts provide the glue of unity in a story of survival

For a land that has experienced such suffering – under Saddam, then under the Americans, and then under attacks from the Isis cult – Robert Fisk finds that a profound dignity nevertheless remains

On the road north of Amara, the storks have built their nests on top of the electricity pylons. Some of these aerial homes are more than six feet wide, a cluster of sticks and long grass at the top of the iron work by Mr Siemens’ descendants. From these fairy houses, the birds espy each other. You can also see their long beaks pointed down as they survey the tiny people of Iraq below them, driving sheep or – amazingly, in the early summer heat – waving green flags in the central reservation of the highway, inviting Shia Muslim pilgrims to stop for free food and water. This is a generous tradition and it is all true. Villagers really do gather beside the road and wave at the drivers heading north, many of them Iranians on their way to Najaf and Kerbala. I got caught in a traffic jam of pilgrims waiting to eat. Not a dinar is paid for this act of kindness.

Perhaps the storks, sweeping down from their pylons on their kite-like wings, appreciate the weird architecture of piety and money below, the human ability to build shrines of such blue- and white-tiled magnificence beside rows of grey garages and cheap concrete furniture stores, lining the old road towards Basra. Can we not create beauty and absolve ugliness from the countryside where the floodwaters are now seeping back into the land of the Marsh Arabs, “droughted” by Saddam in the terrible 1990s? But then I remember how the hovels of the poor were built right up against the European cathedrals of the Middle Ages. Perhaps one gives meaning to the other.

It is the same in the great shrine cities here. You can stumble your way through dust and exhaust fumes before you reach the burial place of the Imam Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law. In Kerbala, the mosques of Hussain and Abbas nestle amid streets awash with grime and slaughtered animals hanging from hooks in fly-blown butchers’ shops. And yet I grew used to it.

Each evening, I would take tea in a run-down cafe where old men smoked hookah pipes. And one evening, I dared to light a cigar which a friend had given me in Beirut. There was a middle-aged farmer sitting on my right. From where did this come, he asked?

From Cuba, I said. Two other men discussed this faraway location. Yes, they knew who Castro was, and I preferred to forget – the moment I remembered it – that Saddam had a liking for cigars. The three men debated this unlikely foreigner in their midst. One of them had a brother tortured and killed in Saddam’s prisons, another brother killed in the 1991 Shia insurrection. Then the farmer fumbled in the chest pocket of his robe and produced his mobile phone. All three surrounded me. They wanted a selfie with the foreigner and his cigar in the holy city of Kerbala.

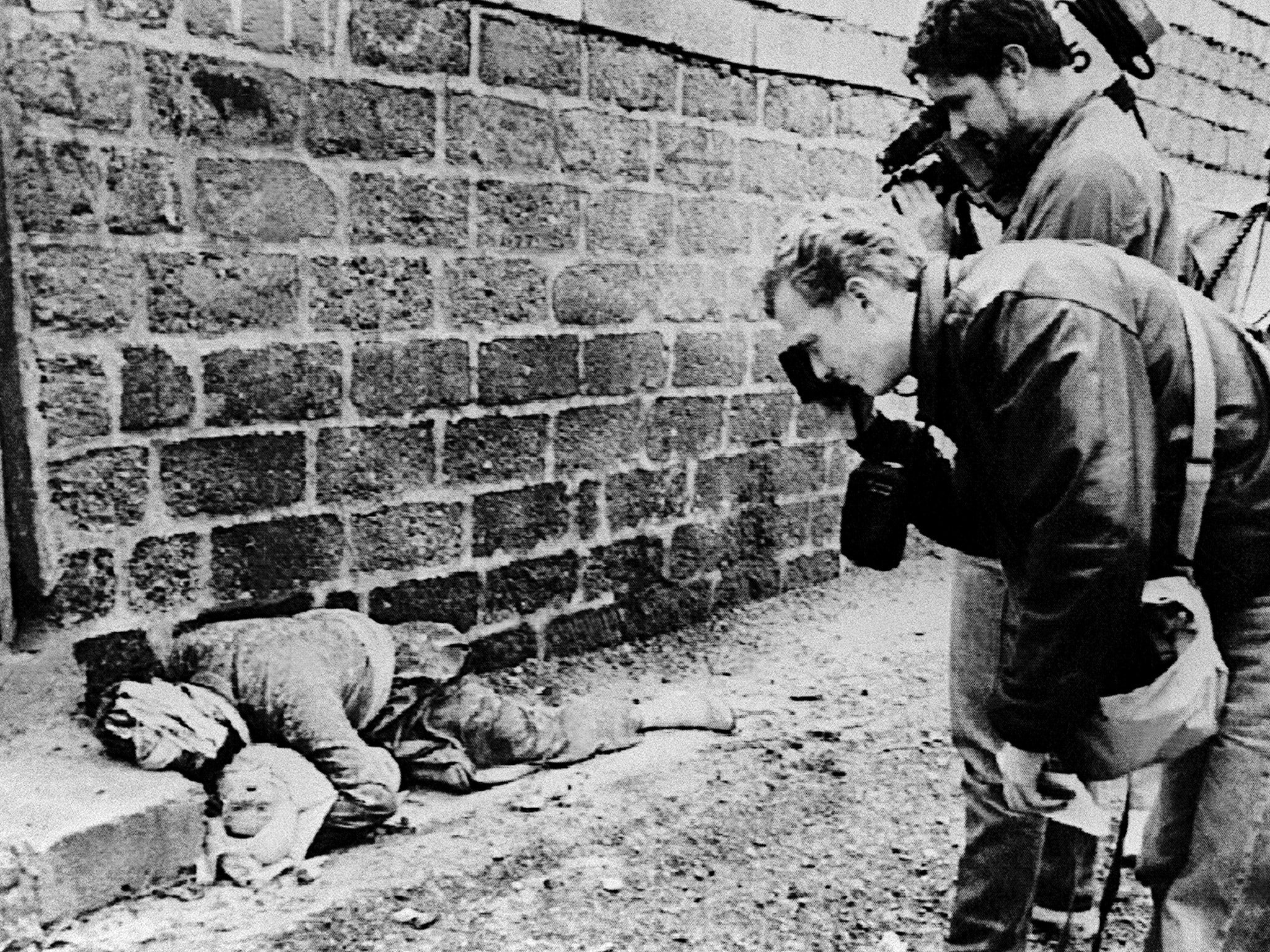

I hesitate to recall how many times the Shias shook their heads in horror and grim wonderment at the memory of Saddam. We correspondents always fear the obvious headline – “Ghost of Saddam Still Looms over War-Torn Iraq” – when it was the Bush-Blair invasion which tore ancient Mesopotamia apart. But Saddam did indeed loom among the Shias.

An acquaintance of mine recalled his 10 years in Saddam’s prisons, watching through the bars as strange lights swished past the gratings in 1991. They were America’s Cruise missiles on their way to Baghdad.

And it is remarkable how often strange sparks of honour shine through these memories, from far-away, distant times when integrity and respect were as rare as they were under American occupation. Here, for example, are the words of an Iraqi friend, speaking of his long-dead father:

“In the early 1950s, the government was throwing the Jews out of Iraq. Tens of thousands of them were forced to sell their lands as cheaply as possible. And of course the Iraqis took advantage of this and bought lovely homes at ridiculously cheap prices. They virtually stole these houses from the Jews. But my father refused to do this. He offered to buy a house from a Jew but insisted that he paid the full price for it, what it would have been worth before the Jews started leaving. He even went to the bank with this man to ensure he received all the money that the house was worth. And, do you know, my father never told me about this? It was my aunt – his sister – who told me what my father had done, long after he was dead.”

American occupation lingers on, not just in Donald Trump’s famous base – from which he thinks he can see deep into Iran – but in the stagnant waters of US policy towards Iran in which Washington has aligned itself with Mohamed bin Salman and Benjamin Netanyahu

And that same evening in Kerbala, I was reading through a bunch of French newspapers I had bought a couple of weeks before in Paris. I have a habit of squirreling away articles to read later. And – by extraordinary chance – I came across a review in Le Figaro of an exhibition about the sale of Jewish art in France under the Nazis between 1940 and 1944. And there was a photograph of the Galerie Charpentier in Paris in July 1944 – after D-Day, I reflected – in which the elite of Parisian society can be seen sitting in the front rows, surveying what appears to be a Renoir portrait.

In the picture, there are chic ladies in feathered hats and bespectacled businessmen with homburgs on their knees. The French, I thought, bought this Nazi loot at rates just as cheap as Iraqis did the Jewish houses of Baghdad in the early 1950s. In the French case, many of the Jews had already been exterminated. One estimate suggests that two million objects – works of art, vintage wine, whole buildings – were sold off under French occupation.

But my friend’s father had kept the faith of his family and, in racist Baghdad of the 1950s, had paid the real price for a Jewish home. It’s only one tale, I know, but it somehow repaid the hope that in a land of such suffering – under Saddam, and then under the Americans and their apparatchiks in the initial occupation governments, and then under attacks from the Isis cult – a profound dignity could still exist, the value of which my friend understood very well.

When we arrived in Baghdad next day, he waved his arms out of the car window across the baking expanse of the city. “It’s much safer, Robert. You can walk in the streets now. Even the Green Zone is open to traffic at night.”

And by heavens, he was right. In central Baghdad, I picked up taxis. And after seven pm, I drove into the Green Zone without even a body check. All across the city, those great, high walls of distress and fear – built between sectarian groups, between occupiers and occupied, between families – have come down. There are cops whistling at drivers who disobey the lights – welcome to the Middle East – but it looked like a city whose heart was beating again, a massive coronary recovery from the years of desolation and death squads.

But American occupation lingers on, not just in Donald Trump’s famous base – from which he thinks he can see deep into Iran – but in the stagnant waters of US policy towards Iran in which Washington has aligned itself with Mohamed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia and Benjamin Netanyahu, a dangerous and unreliable alliance in which Iraq is trapped between the sands of Arabia and ancient Persia.

For Iraqis, the Trump-bin Salman-Netanyahu equation is preposterous. The Iranian foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, put it very well at the Munich security conference three months ago. The US claimed that Iran was interfering in the region, he said: “But has it been asked, whose region? Look at the map. The US military has travelled 10,000 kilometres to dot all our borders with its bases. There is a joke that it is Iran that put itself in the middle of the US bases.”

It was a remark that may look a little grimmer after the apparent attack on two Saudi oil tankers off the Emirates this week. If the US does indeed have a “pathological obsession” with Iran, as Zarif claims, it is Iraq which stands along one of Iran’s front lines. And despite the wish of the Iraqi government and its prime minister, Adil Abdul-Mahdi, to cling to a sort of friendly neutrality, this will become more difficult if the aircraft carrier and naval battle groups and US missiles come too close.

In theory – despite the American desire to destroy the Iranian government – relations between Iran and Iraq have improved. Did not Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani meet Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in March, a clear sign that the Iraqi Shia leadership preferred the more secular and more civilising influence within the Iranian leadership? Is Iraq not trying to broaden its oil capacity to reduce reliance on Iran? A month later, when prime minister Mahdi visited Tehran, the “Supreme Leader”, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, told him to expel the remaining US forces from Iraq “as soon as possible”. Mahdi did not respond.

Looking back, the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war was the first western attempt to destroy revolutionary Iran. The 2006 Israeli war with the Iranian-armed Hizbollah may have been the second. The civil war in Syria – Iran’s only Arab ally – may have been the third

You can hardly blame the Iraqi authorities for looking the other way. Is the city of Basra, with its overflowing sewers and massive electricity cuts and enormous (and violent) public outrage – and huge and profitable oil reserves – not more important in Baghdad than Iran? Are the gestating Isis groups still out there in the deserts of Anbar and around the villages further north not ultimately a greater threat than an American-Iranian war? Iraq has asked America to further exempt it from economic sanctions on Iran until the end of the summer so that it can import more gas and electricity.

But is it really necessary to torture Iraq all over again? There are historical precedents at play in all of this. The Iraqis – not least the Kurds – have largely wriggled out of America’s military grip. No one is quite sure how much of southern Iraq the Shia militias still control. I noticed, south of Kerbala one day, a government army patrol weaving through Shia checkpoints. “They are not supposed to be here,” my driver announced, pointing at the soldiers in their American Kevlar helmets and flak jackets. But what was disturbing is that all the government soldiers were hooded in black masks. And then I remembered that there is still no defence minister in Iraq. Or interior minister.

In one sense, perhaps Saddam does provide the bloody glue of unity. When I heard that militias had discovered another mass grave of Isis victims in Kirkuk, I prepared to set off north of Baghdad. But then it turned out that the latest mass grave had been discovered more than a 100 miles west of Samawa and that the dozens of bodies were not Shia killed by Isis but Kurds murdered during Saddam’s 1988 Anfal campaign.

The president of Iraq, Barhem Saleh – who is a Kurd – was present at the exhumation. These martyrs had died because they wished to live a dignified and free life, he declared. “The new Iraq must never forget the crimes committed at the cost of all Iraqis from all communities,” he said.

And thus is the “new” Iraq urged to remember the old ghost who in 1980, let us remember, went to war with Iran – with US encouragement – in an attempt to destroy the Iranian revolution which Donald Trump, almost 30 years later, now wants to destroy all over again. I still recall how back in 1980, the Saudis supported Saddam’s war and so did Kuwait – and Israel was quite happy to watch two Muslim powers immolate each other – and then US battlefleets set sail for the Gulf and we were told that Iran represented the greatest threat to Middle East peace in generations.

It’s the same old story. And therefore in one sense, Saddam is still alive, his legions still dispensing gas along the Iranian front lines, still destroying the Kurds and threatening the Shias. Nations with long histories tend to survive. Thus will Iran survive. And Iraq. And Syria and Lebanon. Jordan, I’m not quite so sure. And what do we say about Israel? Or Saudi Arabia? And against all this, do the latest trumpetings from Washington really matter? Aren’t we being played a rerun of the same old war?

Looking back, the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war was the first western attempt to destroy revolutionary Iran. The 2006 Israeli war with the Iranian-armed Hizbollah may have been the second. The civil war in Syria – Iran’s only Arab ally – may have been the third. So where will the fourth attempt break out?

Iraq may be sorely tested. But its people, these past 30 years, have been through a most profound purgation – and, so far, they have survived. It might seem flippant – perhaps a little too journalistic – but I wish storks could speak.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments