Growing up in the 1980s: Despite the bombs and dole queues it was a great decade to be young

It was the era when big business, aided and abetted by computers, muscled in on childhood, turning us into adults before our time. William Cook visits a new Eighties exhibition and leaves with mixed feelings

In the Willis Museum in Basingstoke, pop culture curator Matt Fox is telling me about his new exhibition, I Grew Up 80s. He’s funny and engaging but I’m finding it hard to pay attention. I keep getting distracted by all the fascinating stuff around the room. This gallery is crammed with 1980s ephemera, things I haven’t seen for half a lifetime, not since Snickers was called Marathon and Starburst were called Opal Fruits – long forgotten toys and gizmos, and obsolete confectionary (junior shandy and sweet cigarettes – I wonder why they disappeared?) It conjures up that lost age before we retreated into cyberspace – when we lived our lives in the real world, rather than online.

Mention the 1980s to most people under 40 and they tend to run for cover, thinking you’re about to bore them rigid with grim tales of woe about the Miners Strike or the Falklands war. OK, for a lot of adults the Eighties were no fun at all, but if you were lucky enough to be a child it was an invigorating and optimistic era, as Matt Fox’s life-enhancing display confirms.

“If you look back at the newsreel footage, it seems like it was a fairly dreary decade – but it was an incredibly exciting time if you were a kid in the Eighties, and I wanted to celebrate that,’’ he tells me. And he has. His feelgood show evokes an era when girls (and boys) just wanted to have fun. “It was a brilliant time to grow up,’’ says Matt. I couldn’t agree more.

You’d think the Eighties would have been a time of doom and gloom, what with Aids, mass unemployment, and the Troubles in Northern Ireland, not to mention the Cold War and the long shadow of Nuclear Armageddon. Yet perversely, these apocalyptic portents had the opposite effect on youth culture. After the gloomy nihilism of Punk and the (self) righteous anger of New Wave, the New Romantics created a flamboyant, frivolous aesthetic. The real world was far too grim – the only solution was escapism. Even music journalism became more tongue in cheek, as po-faced rock tomes such as the NME were eclipsed by breezy pop mags like Smash Hits. Despite the bombs and the dole queues, it felt like a fabulous time to be young.

Naturally, I’m biased. For me, the 1980s coincided with my teens and early twenties – a time you’re bound to remember with a warm glow, whatever decade it was in. But as Matt walks me round his Eighties collection – stuff from his own childhood, bolstered by more recent additions (hunted down online, and also out in the real world, in good old-fashioned jumble sales) – I realise there’s more to this show than mere nostalgia. As he explains, the 1980s was a transitional time, when computers began to take over. At the start of the 1980s, home computers were virtually unheard of. By the end of the 1980s, they were commonplace, a sign of things to come.

Matt was born in 1972, seven years after me, so his Eighties collection focuses on prepubescent toys as much as adolescent youth culture, but by far the most significant part of his show is these prototype computers. He shows me a ZX Spectrum, launched by electronics entrepreneur Clive Sinclair in 1982. People love to take the piss out of the C5, Sir Clive’s daft electric trike, but they forget what an innovator he was in bringing computers into our homes. Retailing at £125 for the basic model (about £450 in today’s money), the ZX Spectrum sold more than five million units, and introduced a generation of kids to coding. You had to type in every programme, line by line. It took hours and hours, but that didn’t put us off. We had a lot of time to kill back then.

Matt’s dad worked in computers and installed an early modem in their home. Matt must have been one of the first British kids to use the internet, playing a pioneering online game called MUD (Multi User Dungeon), a dungeons-and-dragons kind of game broadcast from Essex University.

For Luddites like me, the closest we ever got to a computer game was in our local amusement arcade. To represent this side of things Matt has found an old Donkey Kong Arcade Cabinet, featuring Eighties arcade games such as Pac Man. Matt has also found an old Atari VCS, the foundation of today’s gargantuan video games industry. The American company sold 30 million of these consoles, even though the individual games cost around £30 a time – more like a £100 nowadays.

These early computer games stand out as harbingers of a brave new world to come, but what’s remarkable about most of the toys in this show is how lo-tech they seem. Care Bears were merely teddy bears with better marketing; Cabbage Patch Dolls were merely dolls with superior PR. Girls still played with Sindy rather than Barbie, shunning the transatlantic supermodel for the wholesome British doll next door (Matt has dug up a Sindy in a Silver Skater outfit, a canny attempt to cash in on the success of Eighties skaters Torvill & Dean).

TV was much the same. In my naivety, I always thought TV’s Max Headroom was some sort of avant-garde robot, but it turns out I was conned. “Tragically, it was a bloke in prosthetics,’’ confirms Matt. “We thought, ‘Wow! They’ve made a computer person!’ But no, it was just a guy in make-up.”

These early computer games stand out as harbingers of a brave new world to come, but what’s remarkable about most of the toys in this show is how low-tech they seem

No one had a mobile phone – only yuppies in films like Wall Street. A few adults had pagers, but kids made do with phone cards. With fewer cars per household, you couldn’t rely on your parents to give you lifts. A bicycle was essential if you wanted to meet up with your mates. You’d be out on your bike all day and your mum wouldn’t know where you were but she knew not to worry, so long as you were home in time for tea.

Two bicycles in the show illustrate the limitations of the Eighties computer revolution. There’s a BMX Raleigh Burner, the most popular BMX bike ever made, apparently: half a million sales in the first two years alone. It’s stylish and sporty but essentially no different from the pushbikes that came before it. Alongside is the Raleigh Vektar. The Raleigh What? Exactly. The Vektar was an expensive flop, the cycling equivalent of the Sinclair C5.

The failure of the Raleigh Vektar is a salutary example of what happens when a clever concept overtakes and outruns the market. The first smart bike, combining hi tech and pedal power, the idea was a sound one, but like a lot of good ideas it flopped because it came along too soon. Launched in 1985 (the same year as Sinclair’s C5), the Raleigh Vektar was a pushbike with an onboard console which told you the velocity, duration and distance of your ride, among other things. To the boffins who built it, it must have seemed its time had come. David Hasselhof had become a big star in Knight Rider, a TV show about a car with a mind of its own. The Raleigh Vektar was Knight Rider for kids – a bike with a brain.

The problem was, this hardware was awfully unwieldy. With all that kit, the bike weighed in at nearly 20kg and cost £300 (around £900 today). Today loads of cyclists use onboard computers to tracks their stats, but these gizmos are light and portable. The demise of the Raleigh Vektar showed there were limits to what Eighties computer technology could achieve.

Indeed, a lot of the bestselling Eighties toys were purely mechanical. An estimated 200 million Rubik’s Cubes were sold within a few years the early Eighties. Transformers merely put a new spin on an old pastime, familiar to dads and grandads who’d been weaned on Dinky toys.

In the Eighties, cinema was integral to youth culture, in a way it can never hope to be today. Nowadays, going to the movies is merely one of many ways to pass the time. Back then, before the internet, movies shaped the zeitgeist – and the Eighties was the decade when the content of the movies altered. After the huge success of Star Wars, Hollywood realised punters wanted pure entertainment, rather than the gritty, realistic movies of the Seventies, so the studios changed course. This shift was reflected in upbeat films like Footloose, Dirty Dancing, Police Academy and Ghostbusters.

Perhaps the biggest difference between then and now was that back then, film and music was something physical – a videotape or a cassette tape you could hold in your hand, rather than something out there in cyberspace. Video rental stores turned every home into a cinema, once you’d bought a video player. “This Betamax video player came out in 1980,’’ says Matt, showing me a machine the size of a large suitcase. “That would have retailed for £750 in 1980.’’ That’d be nearly £3,000 today. Matt bought this one for £15. “It weighs an absolute ton, covered in buttons, but at the time it was an amazing piece of technology, and it would have cost you a month’s wages.’’

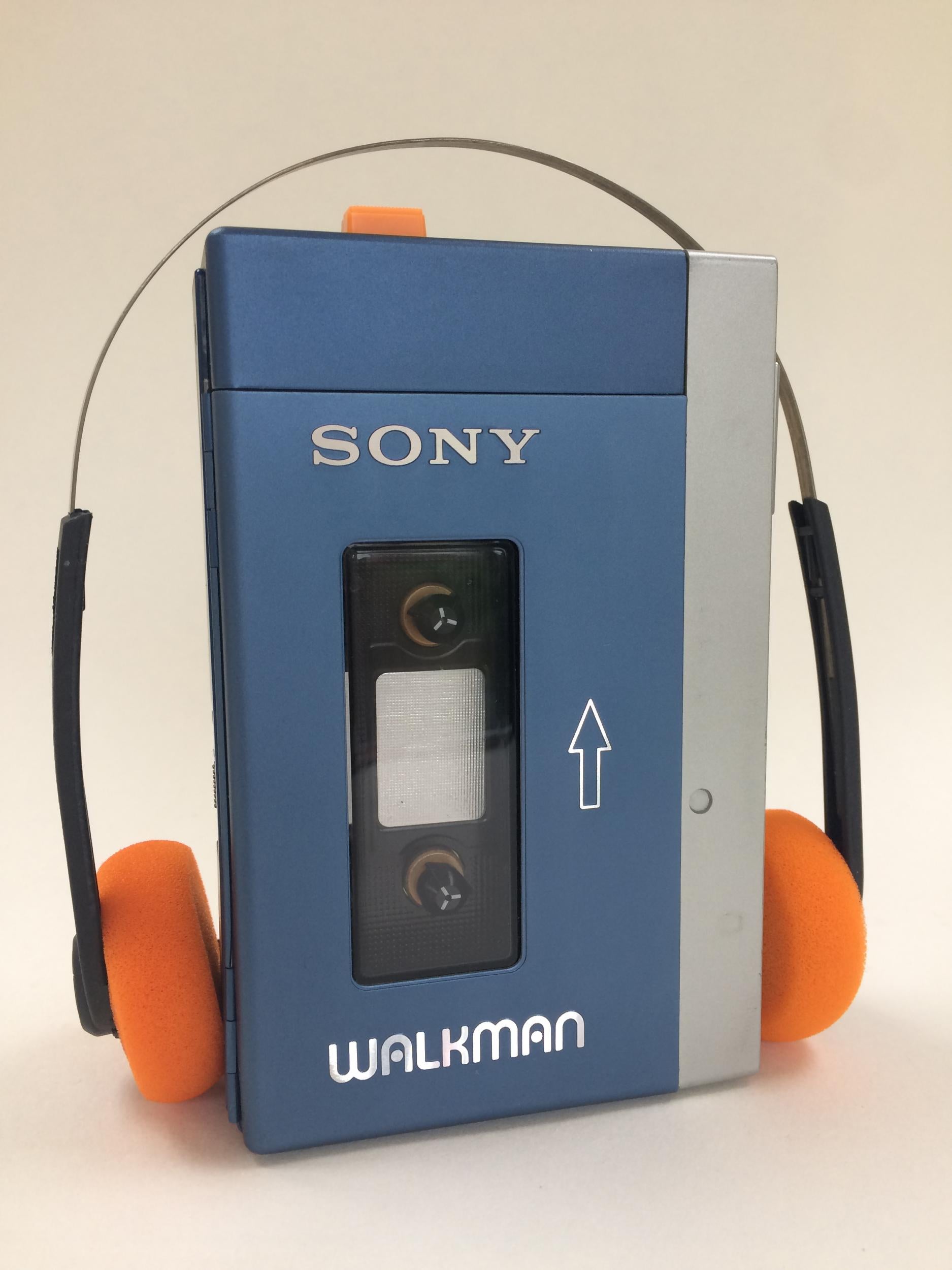

While video players took cinema into the home, the Walkman took music out of the house and on to the street, paving the way for today’s smartphones. “It prepared the way for the personal tech we have today,’’ says Matt. “Nowadays you go on any tube or train, and most people have got headphones on.’’

Compared with modern tech the Walkman was pretty clunky, but its minimalist design still looks cutting edge today. Conversely, Eighties ghetto blasters revelled in unnecessary complications. For this show, Matt has tracked down a Casio KX-101, aka the King of Boomboxes. It boasts 131 dials and buttons (mostly superfluous) and weighs a shoulder-busting 8kgs. The more knobs and whistles, the better – never mind what they were for.

One of the most significant changes in the Eighties was the rise and rise of designer brands. It’s hard to imagine nowadays, when every teenager and twentysomething is clad head to toe in branded leisurewear, but back in the Seventies designer logos were virtually non-existent.

At the start of the Eighties, a trip to your local sports shop to buy a pair of trainers (or plimsolls, as our parents called them) meant a choice between two or three rudimentary styles. Back then, Dunlop Green Flash was the flashiest training shoe on the market. Now there are hundreds to choose from, and it all started with Adidas Hi Tops, as worn by Michael Jordan and Run DMC.

"As soon as these things came out they made the trainers of the Seventies, represented by Green Flash, seem hopelessly uncool and outdated.'’ This, to my mind, is probably the worst thing about the Eighties – the way consumerism took hold, and made children so self-conscious.

So what does I Grew Up 80s tell us about the decade that taste forgot? As a sad old sod pining for my lost youth, I really enjoyed Matt’s show. For anyone old enough to remember leg warmers and Ra-Ra skirts, it’s a great trip down memory lane. But I must admit I left the gallery feeling more downbeat than when I went in.

I’d never really thought about it before, but it struck me that this was the decade when big business, aided and abetted by computers, muscled in on childhood, turning us into young adults before our time. Jackie made way for Just Seventeen – a massive seller, half a million circulation in its heyday. The content was harmless, but the clue was in the title: girls in their early teens were now in a frantic hurry to grow up.

The Eighties was also the advent of today’s celebrity culture, as Matt reminds me as we stop in front of the sleeve for that infuriatingly catchy single, ‘When Will I Be Famous?’ by Bros (I wonder what became of them?) ”It was a long time before Big Brother but it really speaks to today,’’ he says. “That was back in 1987 and that question is much more relevant now.’’

A poster for Michael Jackson’s Thriller has pride of place – Matt could hardly leave it out, since Thriller was (and still is) the bestselling album of all time. For Matt, the cultural importance of this poster is all about the music video. “It represents the power of MTV better than any other because it was like a mini movie.’’

Indeed it was directed by John Landis, who directed Eighties blockbusters such as The Blues Brothers, Trading Places and An American Werewolf in London. Yet today this poster has become a kind of Picture of Dorian Gray – a perfect portrait in the attic of a man destroyed by fame.

But there’s a brighter side to the Eighties too, a time of euphoric films and music and daft, endearing dress sense. “Girls’ fashion in the Eighties was very bold, very empowering – dressing like little superheroes, lots of bright colours, big shoulders, big hair,’’ says Matt. “There was a lot of feminine strength and feminine empowerment.’’ For women, the submissive sexuality of the Seventies made way for something far more powerful. The new woman of the Eighties was both gutsy and sexy, often distinctly androgynous, personified by pop stars like Annie Lennox and Grace Jones.

We never thought Seventies fashion could ever become hip again, but it happened – so is the Eighties ripe for a revival? Matt certainly thinks so. “I’m amazed how much the Eighties look has come back on the high street this summer,’’ he says. “Paul Smith’s collection is all leopard prints with little pink offsets!’’

In a way, the Eighties never went away. Film franchises such as Mad Max and Die Hard have proved incredibly durable. There’s even a new Raiders of the Lost Ark movie in the pipeline. My kids are both teenagers. They ought to hate the Eighties, but they both love Eighties films and music. They adore movies like Uncle Buck and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, made long before they were born. The other day I heard my 19-year-old son singing along to Sister Sledge.

Other aspects of the Eighties are already back in vogue. Vinyl is cool again (although I’m still waiting for the renaissance of Eighties coloured vinyl and picture discs). Even cassette tapes are becoming retro chic. “People appreciate that chunky analogue technology,’’ says Matt. Even people too young to have ever made them are becoming nostalgic about mix tapes.

The Eighties was a time when we all shared the same culture. It wasn’t any better than today’s pop culture, but it was a culture we all had in common. We all saw the same movies, we all watched the same TV shows, because we didn’t have any choice, and so it was something we could all talk about – unlike today, when we’re all doing our own thing, all together, all alone.

“I could sit down now, even today, and I could speak to someone else who grew up in that period, and I could say, ‘I have a pretty good idea of what you watched on TV, and I know what games you had at home, and I know what you listened to – because I did those things too’,’’ says Matt.

I know exactly what he means. Back in the Eighties, to have all the entertainment we have today would have seemed like a dream come true. But guess what? Now we’ve got it all, it doesn’t feel like so much fun anymore.

I Grew Up 80s is at the Willis Museum and Sainsbury Gallery in Basingstoke until 14 September, and then at the Gosport Gallery from 27 September to 31 December; www.hampshireculture.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks