An Australian mining magnate wants to save the planet with green hydrogen

Andrew Forrest is switching from iron ore to producing hydrogen fuel. What are his motives, asks Evan Halper, profit, or conscience?

The Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest expresses few regrets about his iron ore mining company and its partners, having pumped millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, or the bitter legal conflicts with Aboriginal officials over ecological destruction allegedly committed by his firm, Fortescue Metals Group. He prefers the label “heavy industrialist.” Don’t call him a “greenie.”

Yet as the world reaches an energy inflexion point, Forrest is now a point man for audacious climate action, with his sights set on the United States. He is betting the future of his $34bn company on a plunge into “green hydrogen,” a superfuel theoretically capable of powering jet planes, large machines and even electricity plants without any carbon footprint.

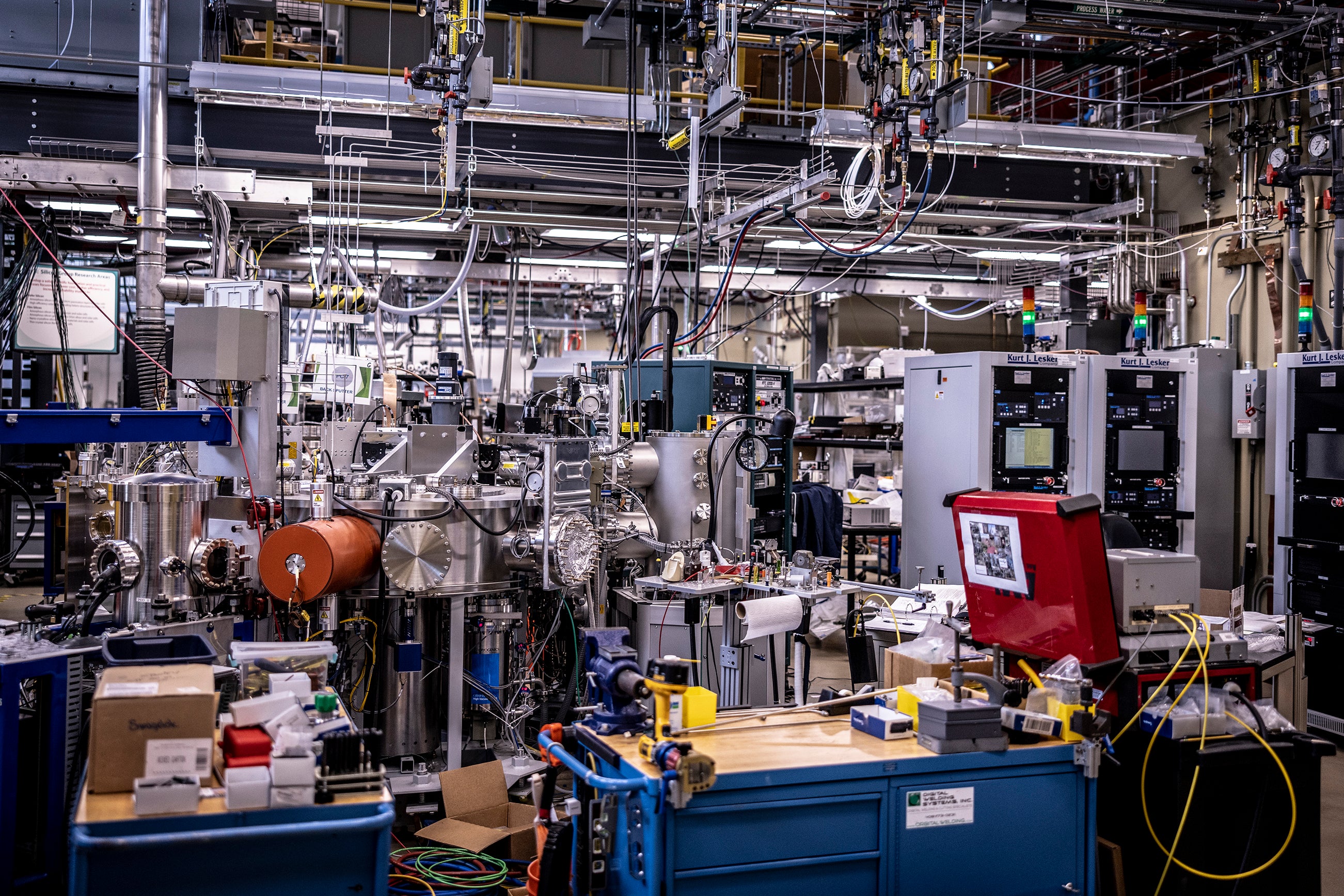

The headwinds are fierce. Hydrogen gas is made by separating water molecules, and producing it typically requires massive amounts of climate-unfriendly natural gas. So far, no one has been able to make affordable hydrogen fuel produced entirely with renewable sources of energy. It requires too much wind or solar power to be practical for mass production. Scientists are racing to change that, with Forrest placing a huge wager on their success in bringing green hydrogen to market quickly.

Forrest says he will make 15 million tonnes by 2030, a scale and pace others doubt. The billionaire boasts he will erase fossil fuels from Fortescue’s operations and supply huge quantities of the new fuel to others.

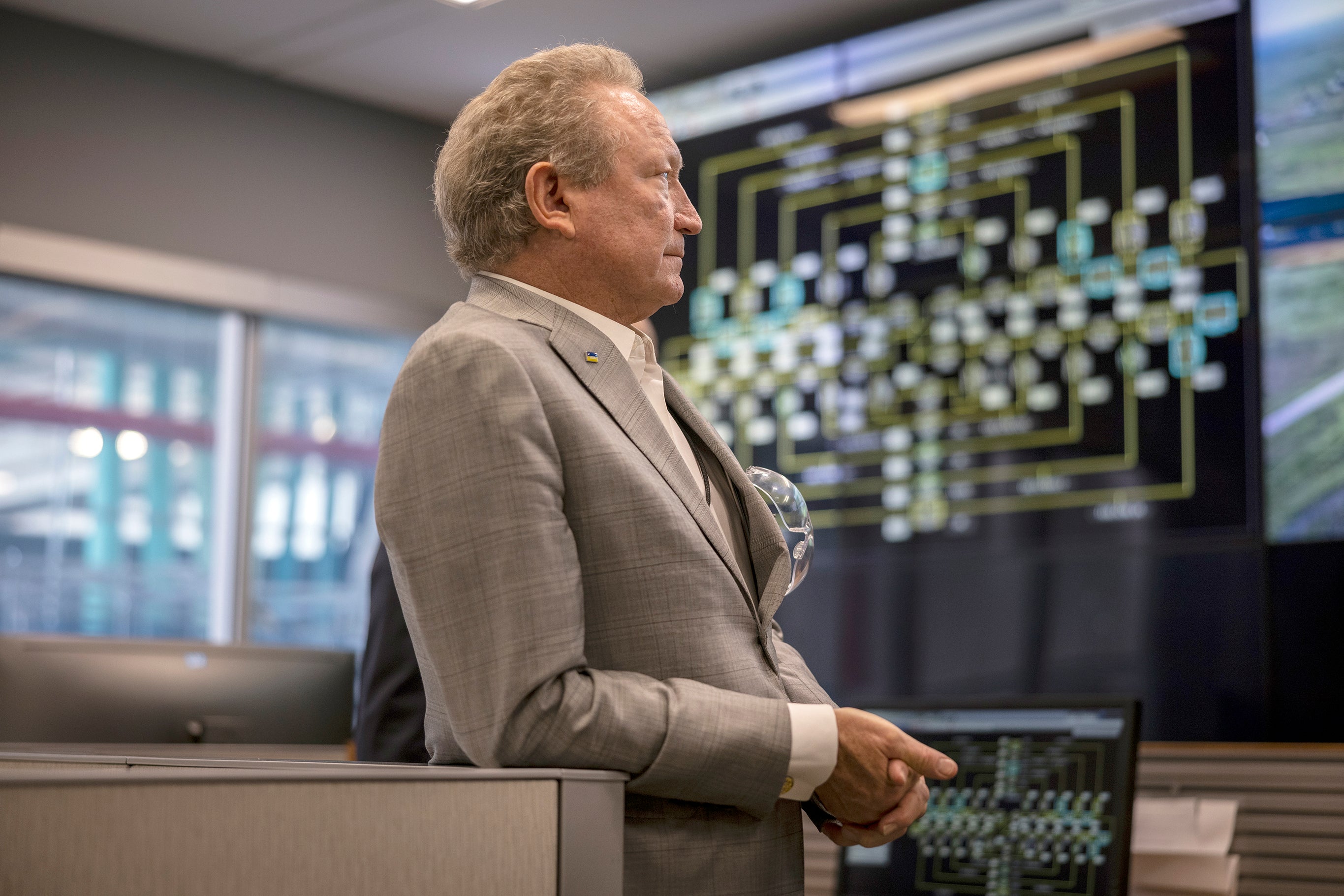

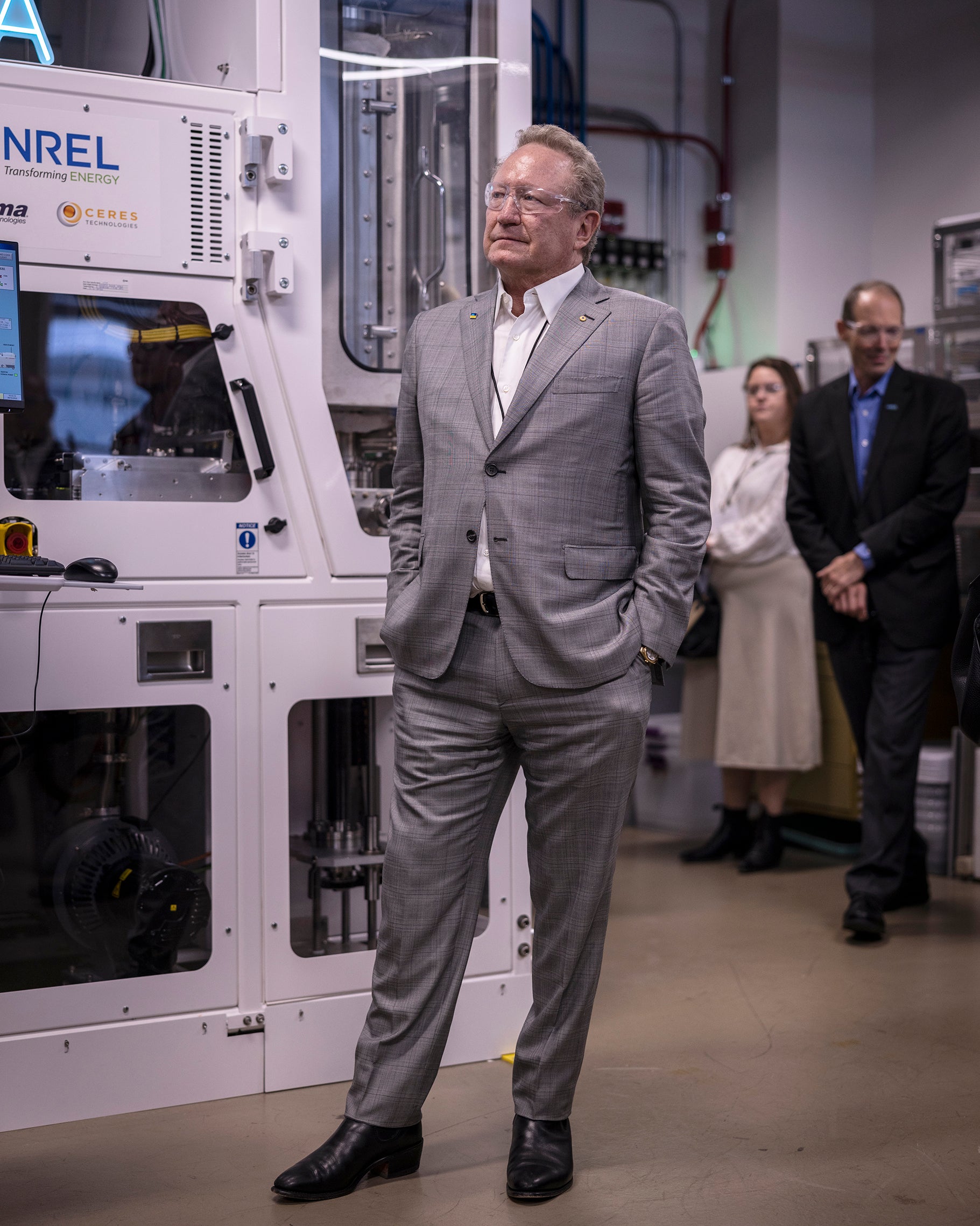

“Some are arguing that the technology we need to beat global warming is not with us yet,” Forrest says as a black SUV zipped him from his penthouse suite at the Denver Ritz-Carlton earlier this Spring to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which is collaborating with him. “I say that is completely false. The most optimal technologies aren’t with us yet, but we’ve got enough now to make huge heavy-industry companies green.”

Forrest’s vision became a lot less fanciful with the Inflation Reduction Act, the historic climate measure enacted by the United States this summer. It is drawing wealthy investors from around the world to pursue all manner of clean energy projects in the United States. The law promises green hydrogen producers a subsidy unmatched anywhere. That $3/kg could move this curious form of energy out of the lab and into mass production.

“It has let the genie out of the bottle,” Forrest says. It has also pushed the executive into the ranks of the climate billionaires, playing the role of an ambassador for green hydrogen on such prominent stages as the UN global climate summit, Cop27, which concluded recently in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

Forrest traces his quest to a near-fatal hiking accident in 2016. He plunged off a cliff into the water, where he had to pry his shattered leg from a rock. “It was brutal,” he says. “I could have lost my life.”

Forrest earned a doctorate in ocean studies during his recovery, learning about the catastrophic changes being wrought by methane released from thawing Siberian permafrost. It convinced him the world’s timeline for climate action is inadequate.

“The fossil fuel industry has been saying we’ll evolve into this and get it right by 2050,” he says. “They can’t say that anymore. The problem is now.”

Forrest readily admits this is as much about chasing corporate profits as clearing his conscience.

Fortescue’s intention to produce enough green hydrogen to power the equivalent of 60 million diesel cars by 2030 has sent Forrest around the world, striking tentative deals to build plants and import terminals. The company has committed $6.2bn, with its plans stretching from the deserts of the Middle East to European industrial zones. The Australian Outback will host facilities, and repurposed coal mines in West Virginia and other states are being scouted.

The technology is hotly debated by fellow corporate change agents: Elon Musk mocks it as foolishly impractical, while Bill Gates sees it as crucial to a carbon-free future. Forrest seeks to make a name alongside these climate-minded billionaires.

“He’s not waiting around for people to do what we’ve been doing, which is procrastinate for years,” says US Climate Envoy John F Kerry. “He could help change thinking.”

Getting machines to run on hydrogen is not complicated. Industries have been using hydrogen for decades, in the oil refining process, to make fertiliser, and as fuel to propel rockets into space. There are several thousand hydrogen cars in California and a smattering of hydrogen-fueled passenger trains and city buses around the world. The Inflation Reduction Act’s hydrogen subsidies, totalling $16bn, have lowered the cost of making hydrogen with renewable power so much in the US that many analysts project it will be priced competitively with dirtier varieties as soon as the science catches up.

“Hydrogen has suddenly been recognised as a needed component in the drive to decarbonise,” says Frank Wolak, president of the Fuel Cell & Hydrogen Energy Association. “The Inflation Reduction Act is a kind of accelerator.”

The speed at which green hydrogen comes to market hinges on how much innovation can happen quickly around machines called electrolyzers, which turn water into hydrogen fuel by separating out the oxygen. The Biden administration is investing heavily in next-generation electrolyzers that can make the fuel with considerably less energy. White House National Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi compares electrolyzers to the battery components the Obama administration invested heavily in to accelerate the transition to electric cars.

This is, after all, a man who has produced zero green hydrogen so far. The signals he is sending are positive, but we are missing some key pieces to make a judgment on how good this ambition is

Oil and gas companies are eager to dominate the hydrogen landscape themselves. They would continue using natural gas to make much of it for now, pairing production with carbon capture technology meant to trap the emissions.

In a bit of marketing spin, the industry calls it “blue hydrogen.” Forrest calls it bunk.

“It is proven unreliable,” Forrest said of carbon capture technologies at a clean energy event in Pittsburgh earlier this year.

“Would any oil and gas executive count on an unreliable technology to save the life of their child when there are reliable options available?” Forrest asked.

He’s also competing with the nuclear industry, which is pushing to power hydrogen production with its technology. The nuke-powered fuel has its own colour label: “pink” hydrogen.

The Biden administration is supporting all in the hydrogen colour wars, giving the biggest subsidies to those who can produce truly green hydrogen and leaving the market to sort it all out.

The frenzy across the US to take advantage of the new federal money for green hydrogen brought Forrest together with Colorado Governor Jared Polis in September to announce a partnership. It had already been an eventful day, with Forrest arriving for his tour of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory with Kiss rocker Gene Simmons, whom the billionaire considers a buddy. Simmons said the two like to wax philosophical.

Polis wasn’t sure how to address Forrest, who goes by the nickname “Twiggy” (he was skinny as a kid). Polis went with Twiggy. It was awkward, like everything in this alliance between liberals and the heavy industrialist.

“This is, after all, a man who has produced zero green hydrogen so far,” says Rachel Fakhry, a hydrogen expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “The signals he is sending are positive, but we are missing some key pieces to make a judgment on how good this ambition is. We need to make sure what he makes is actually green.”

The outlook for how exactly green hydrogen would be used is murky. The amount of wind and solar power it takes to produce, and the tremendous cost involved with storing and shipping the final product, probably make it impractical for fuelling passenger cars, for example.

California heavily subsidised a “hydrogen highway” experiment, but it has largely proved a disappointment. There are fewer than 10,000 of the cars on the road in the state, almost entirely burning hydrogen made with fossil fuels.

“Every generation since the 1970s has had this idea that the next generation will be driving hydrogen cars,” says Martin Tengler, lead hydrogen analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “We tell people: you don’t drive a hydrogen car and neither will your children.” But his organisation is bullish on the use of hydrogen for other machinery, and it and other groups, including the think tank Carbon Tracker, predict the clean variety Forrest is chasing will dominate a hydrogen economy that could grow to $3tn by 2050.

Whether it will scale up on the timeline set by Forrest is a separate question.

Last spring, Forrest went to a coal power station in West Virginia to pitch rank-and-file coal miners on the future they could have in hydrogen. He stressed how decommissioned coal facilities present a prime opportunity for hydrogen production, with much of the needed infrastructure and workforce readily available.

“You know, they are not married to that black stuff, which can eventually kill you,” Forrest says. “They’re in coal only because they love their community, their families, their careers. If they have another medium, which is going to be even better for their community, their families, their careers, they’re going to switch straight up.”

The overtures in West Virginia got the attention of the state’s Democratic senator, Joe Manchin III, the driving force behind the Inflation Reduction Act, with whom he has met. Forrest also presented his plans to President Biden at a White House meeting, he says.

Back in Australia, Forrest is alleged to be both charming and manipulative. He built his iron ore mining empire on the same kind of risky gamble he is making on green hydrogen. He bought up tens of thousands of kilometres passed over by the existing big mining companies as unsuitable for extraction, as the iron ore deposits were less abundant and would take extra effort to pull them from the earth. The extraction process used on some of the Fortescue plots is particularly destructive to the environment because it involves scraping over a large surface rather than digging deep into concentrated areas.

With demand for iron ore exploding in China, Forrest saw dollar signs on the subpar land where competitors saw headaches. His company now has more than 15,000 employees.

Critics in Australia, including indigenous groups such as the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corp, wince at Forrest’s reinvention, branding it greenwashing.

The billionaire frames his $6.2bn plan to eliminate fossil fuels from Fortescue’s mining business by 2030 as less about altruism than corporate acumen, a move the company projects will save $818m a year in diesel and gas costs and drive healthy returns.

“People said: ‘You’re going to be screwing up your dividend,’” Kerry says. “No, he’s not. He’s going to make more money. And he’s going to do it the right way. That’s a really important thought for everybody to have out there. This can be done.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks