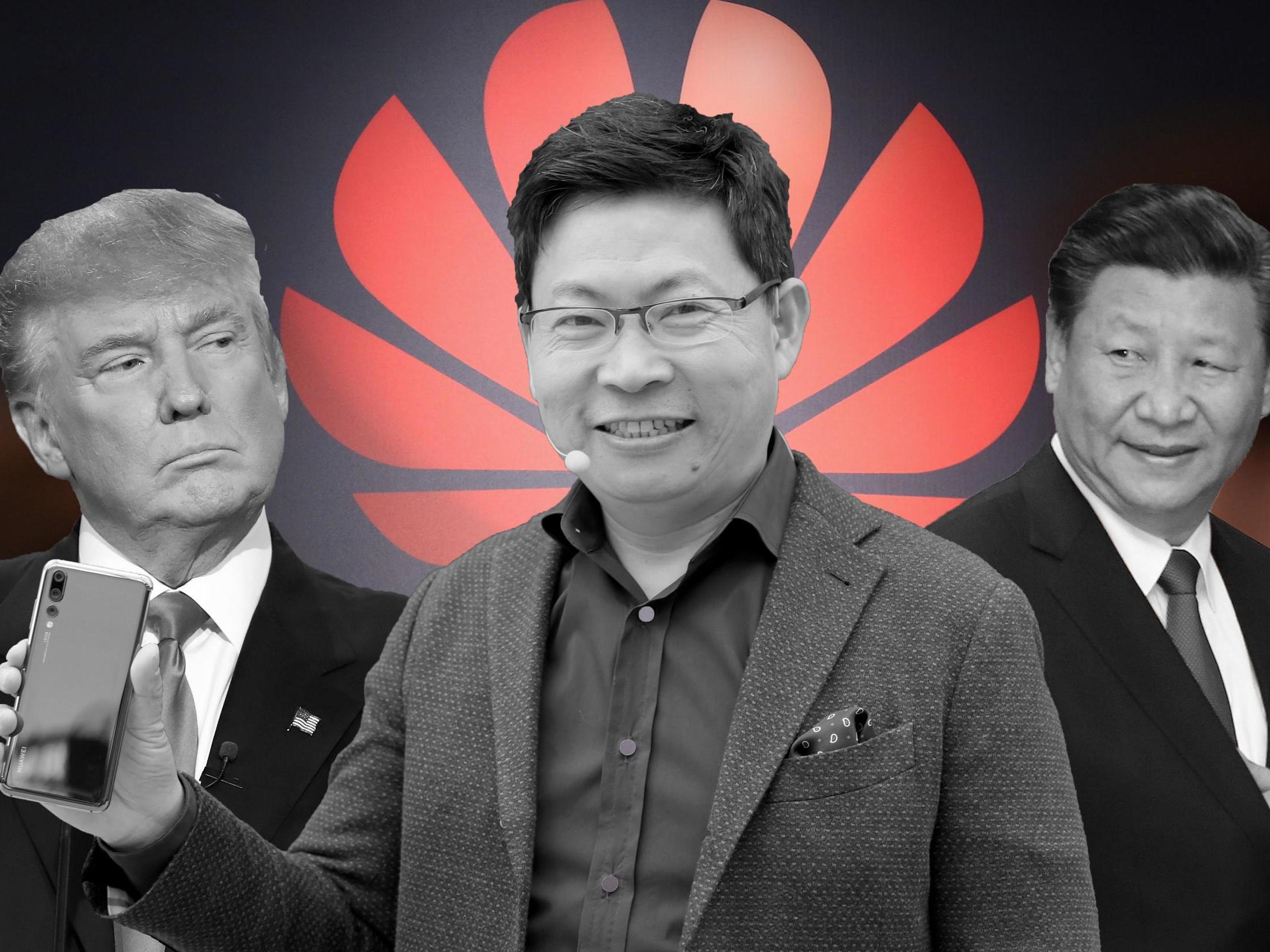

Who is really calling the shots on Huawei?

Does the Chinese company’s 5G technology pose a real security threat to other nations or is it just Google and Donald Trump spinning a world wide web, Mick O’Hare asks

It would be rare, it is fair to say, for most readers of this publication to sympathise with Donald Trump. But the president of the United States elicited some support in liberal circles on both sides of the Atlantic when he suggested that the forthcoming 5G phone networks of what we sometimes describe as the free world should not be developed and operated by Huawei, the Chinese technology company.

In May, Trump signed an executive order banning information technology transactions between US companies and “foreign adversaries”, placing Huawei on the US government’s “entity list”, meaning US companies who wish to trade with it now need a licence. Huawei relies heavily on US firms to build and operate its phone networks, so with companies as diverse as Google, EE, Vodaphone and Panasonic already acting on Trump’s order, Huawei is effectively being squeezed out of the American market.

British and other non-US companies have followed suit. Trump and his administration have accused Huawei of being too close to the Chinese government – insisting it is effectively an arm of the state apparatus – and that its tech will be used to spy on the western democratic alliance. Huawei denies the accusations.

Of course, this fits with the pattern of Trump’s nationalistic Make America Great Again presidency, and his desire to engage in a trade war with China. But put that to one side and consider instead the dreadful human rights record of Beijing, and its almost certain desire to interfere in or at least have greater knowledge of the activities of the west, and you’ll see why some liberals think Trump may have called this one right. Shades of Cold War paranoia? Possibly, but would the British government have outsourced the UK’s forthcoming 5G upgrade to the Soviet Union back in the day, or even contemporary Russia under Putin now?

When former defence secretary Gavin Williamson leaked (allegedly) information that Huawei would be providing the technology to upgrade Britain’s mobile phone network to 5G, the opposition was loud and vocal, from both sides of the Atlantic. Williams expressed “grave concerns” about Huawei and accused the Chinese state of sometimes behaving in “a malign way”. In response, Wu Qian, a Chinese defence ministry spokesperson, said Williamson’s comments “just reinforced the deep-rooted ignorance, prejudice and anxiety among some British people”.

But before we tackle the politics of the situation, both in the west and China, what exactly is 5G and why might it have caused the kind of consternation among governments and tech experts that has led to the US ban?

Fifth-generation networks (or 5G) combine a number of technologies being developed separately that together lead to a huge increase in the speed and responsiveness of mobile phone and wifi networks. At high frequencies, many closely packed users, such as sports fans in a stadium, can access the internet without loss of performance, while at low frequencies it has massive geographical reach. It is all things to all users.

The network is being rolled out throughout the world and can support up to a million devices per square kilometre, more than 10 times the capacity of current 4G networks. Surgeons recently used 5G technology to direct operations over the internet, so quickly can the technology react – 5G is also set to be a key component in the development of smart homes and driverless cars. Huawei is generally considered the world leader in 5G tech, and is lauded by many users both for its proficiency and affordability.

Ana Santos, formerly a software engineer at Portugal’s largest telecoms provider, Altice Portugal, says: “My perception is that the Chinese tech is improving faster than American tech and this does not suit Trump. I use Huawei and it’s superb.”

So, if we are to take Trump (and Williamson) at their word, does it really offer unprecedented opportunity for espionage? Will the Chinese effectively have a spy in every home in the west, let alone government departments, nuclear power stations and, who knows, the changing rooms at Manchester City? Is 5G any more vulnerable to manipulation than previous generations of mobile phones?

“Well, arguably yes,” says one US-based phone hacker who, for obvious reasons, wished to remain anonymous. “Any new technology opens up opportunities. But you would have to question why the Chinese state, or Huawei itself, would choose to do that considering every western security service and every hacker would be looking for it. Keeping it hidden would be very difficult.” But Nicholas Weaver, a staff researcher at the International Computer Science Institute at the University of California, disagrees. “Sabotage can be really subtle,” he says. “A single microscopic difference and you lose all your assurances.”

But technology and spooks aside, is this instead all a matter of Trump fighting his trade war with the Chinese? After all, Huawei is the largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment on the planet, its networks reach a third of the world’s population and it recently overtook Apple to become the second biggest maker of smartphones in the world, behind Samsung.

The US has fought a running battle with Huawei for a decade at least. In December, Huawei vice chair Meng Wanzhou – daughter of Ren Zhengfei, Huawei’s founder – was arrested in Canada on a US warrant, ostensibly for violating sanctions against Iran, to put alongside an accusation that Huawei stole trade secrets from the US arm of T-Mobile.

China believes the charges are, to use an appalling pun, trumped up and politically motivated – merely part of the same concerted attack on its businesses. It might be argued that the spying allegations have simply provided Trump and his hawks with the perfect pretext. Zhengfei predicted as much when he claimed Huawei was as many as three years ahead in terms of technology, expecting that it was inevitable “there will be conflict with the US”.

Which leads us to the source of American distrust (some might consider it outright, or at best faux, hatred). It is no surprise to hear politicians such as Republican senator Marco Rubio singing from the hawkish songsheet by stating: “Huawei is a Chinese state-directed telecom company with a singular goal: undermine foreign competition by stealing trade secrets and intellectual property. We must recognise that the threat posed by the Chinese government’s assault on US intellectual property, US businesses and our government networks and information has the full backing of the Chinese Communist Party.”

Any new technology opens up opportunities. But you would have to question why the Chinese state, or Huawei itself, would choose to do that considering every western security service and every hacker would be looking for it

He is correct in arguing Huawei does not operate like western companies in a free market. It is classified as a “collective”, which is employee-owned with most of its shares held by the company’s trade union. How much the trade union is subsequently controlled by the government is a matter of debate. Certainly the International Trade Union Confederation does not recognise China’s national All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) as independent of the government.

For its part, the ACFTU points out that western companies via their owners and HR departments continually try to hamper the activities of trade unions in their nations. And while Qing Wang of Warwick Business School, quoted in The Verge, points out that “the CEOs of Chinese private enterprises are not government officials”, what is certain is that the Chinese government can exercise control over whatever business interests it chooses to, far more than the government of a western free-market economy could (or normally would).

China has plans to pass new laws requiring Chinese companies which transfer “important data” to also store that information in China. You don’t have to be a government spook to realise this will create quite a large database of information that might be of interest to the Chinese government.

Yet as British science weekly New Scientist has said: “The fears may be unfounded anyway. Sensitive data should never be sent over a public network without being encrypted. Even if the message is intercepted, it’s nearly impossible to read. Additionally, so far no evidence has made it into the public domain showing that Huawei has mishandled data or is tied up with the Chinese state.”

In addition, The Washington Post’s Cybersecurity 202 column has questioned whether blocking American companies from making products for Huawei is counterproductive. It reported that “cybersecurity experts worry the ban will diminish US influence over the security of new technologies”. China will go it alone, runs the argument, to become technologically independent and so become more likely to introduce questionable practices, instead of being deterred. Chris Finan, cybersecurity director under former US president Barack Obama, has described the ban as an “act of self-immolation in the name of security”.

Nonetheless, surely it would be naive not to guard against espionage in whatever form. Russia has been accused of waging cyberwarfare against the west in recent years – interfering in elections and the Brexit referendum. The Kremlin may even have swung things for Trump in 2016. So it’s not being anti-progressive to presume the Chinese – as well as our own and our allies’ – governments are equally implicated in cyberwarfare, whatever their motivations or ideology.

China already restricts its civilians access to the internet, and Russia is flirting with the idea of disconnecting the nation from the world wide web, ostensibly to test how resilient it would be in times of “national emergency”. China would almost certainly be tempted to follow suit. And let’s not forget that dreadful Chinese human rights record (one, according to an anonymous wag in Huawei’s European arm, that Trump himself would be proud of). Torture, imprisonment and disappearance of dissidents and others is one reason some liberals sided with Trump. Why would any government committed to democratic freedom help prop up the Chinese state by purchasing its products?

So is the apparently pugnacious distrust shown by the Trump administration genuine, imagined or played-for political expediency? As ever with this president, his actions are likely to be intertwined between the political and the commercial. China has been a bogeyman for Trump since the beginning of his presidential campaign. He saw it as the reason for a loss of jobs in America’s traditional manufacturing industries, and by picking on it he is playing to his nationalistic base, “putting America first”.

Only last month Trump almost doubled duties on Chinese imports. Unsurprisingly, China responded in kind. But by facing off against the United States’ ideological and international business competitor, he wins support at home while continuing to fight his trade war against what he sees as China’s previously advantageous access to American markets.

As Hamish McRae noted in The Independent in May, because Huawei is the world’s largest telecom equipment manufacturer, it would be naive to think a president who based his election on “Make America Great Again” might not consider this a threat to his often vacuous promises. But Trump is also responding to intelligence from his security agencies regarding what they consider to be genuine threats from Huawei’s tech – intelligence the British government has either chosen to ignore or, at best, believes it has the ability to counter.

Because the hounding of Huawei so easily falls into the simplistic narratives pursued by the Trump administration of trade protectionism and dislike of “the other” – taking note of his immigration policies – it is difficult to ascertain whether the key claim is genuine. Does Huawei’s 5G technology pose a real security threat to other nations? “There is no hard evidence to support this notion,” says Qing Wang. “If anything, it is in the interest of Huawei and the government to see its reputation and technological leadership continue rather than being ruined by scandals such as espionage.”

“While it would be straightforward enough to build spyware into phone software or hardware,” says an anonymous UK-based phone hacker and cyberfacilitator (his terminology) contacted by The Independent, “you’d have to ask: why? Are you merely spying on private citizens in the privacy of their homes? Salacious and unpleasant, but what would you learn? Or are you hoping to spy on government organisations – surely the only reason the Chinese state would be interested? Or is it bigger?

“Are you hoping to be able to crash entire networks, disrupting civil society, security and public confidence? You have to have a motive, otherwise it would be simpler just to bug the Downing Street cat, or pay civil servants or untrustworthy politicians to spy for you. And if you did bug the software you’d have to make sure it wasn’t discovered by your opposite numbers in foreign intelligence services who would doubtless be looking for it. Too many ifs, too many buts.”

And as Santos adds: “Even if the Chinese are spying, what’s the difference between that and what Google knows about me? It seems to know where I am, who my friends are, what I am buying and where I am eating. What else does it know about our governments?” Huawei’s chair, Liang Hua, has said as much himself, finding it hypocritical that the US government accuses it and China of espionage while the US’s National Security Agency spies around the world.

For the record, Ren Zhengfei has stated Huawei has “no back doors”. It would be pointless, serving only to destroy his business overnight if it were discovered, he points out. Jason Perlow, of the Tech Broiler blog, agrees: “If it were discovered that China was, in fact, using consumer electronics exports to spy on American citizens and businesses, the consequences would be utterly disastrous for it. It would throw the global consumer electronics industry into utter chaos. It’s not as though any state-sponsored malware has even been detected in a Chinese component.”

Huawei is fighting back. The company is challenging the US government’s decision in court, saying it violates the US constitution and will adversely affect millions of consumers. Elsewhere, Huawei has even offered to sign a “no spy” agreement with the British government to reassure politicians (and users).

Even if the Chinese are spying, what’s the difference between that and what Google knows about me? It seems to know where I am, who my friends are, what I am buying and where I am eating. What else does it know about our governments?

But all of this seemingly holds no truck with Trump and his cohorts. And the loss of Huawei and its advanced technology would be a tiny price to pay for the president to win his trade war with China. He will take any opportunity to keep the US ahead economically, politically and, in all likelihood, militarily. Writing in The New York Times, Thomas Friedman argues that it “it took a wrecking ball like Trump to get China’s attention”.

Meanwhile, pressure is now mounting on the British government to follow Trump’s lead and review its decision to use Huawei’s technology. Theresa May appeared to backtrack slightly during Trump’s state visit in early June. And maybe a new prime minister more favourable to Trumpian discord might too have a change of heart. Conservative leadership candidates Sajid Javid, Esther McVey and Jeremy Hunt have already said they will reconsider the proposals, while Woody Johnson, US ambassador to Britain and a Trump appointee, has advised the UK to move with “caution” on the issue.

Meanwhile, The Washington Post has reported Trump may be prepared to restrict intelligence cooperation with Britain in order to bring the government round to his point of view. But British security experts say they have tested the software and infrastructure and are confident it contains no threat. They also say Huawei will only have access to the edge of the 5G network, keeping the core secure.

Thus far the government – along with those of Germany and France – has resisted US pressure, although some British companies with roots in America have not, and security officials in all nations have urged caution. However, Japan, Australia and New Zealand have placed restrictions on Huawei technology. Security analyst Robert Emerson was reported in The Independent as saying: “The UK will have to choose between China and the US, and I can’t see the UK taking on the US.”

So what of the future? Well this one looks set to run and run. Even beyond the Huawei kerfuffle, the trade war seems set for tit for tat. American tech giants could be set to lose out as much as Huawei because their products are losing access to Chinese markets as the Asian nation fights back. China is already drawing up a list of “unreliable” foreign companies likely to cause “harm to Chinese interests”.

Elsewhere, access to academic institutions in both countries seems about to be restricted, as does investment both ways. It’s been hinted that China, with its natural resources of rare minerals used in everyday products such as rechargeable batteries and computer screens, and also in low-carbon technologies such as hybrid cars, could restrict exports. Key industries in the US and elsewhere are currently reliant on their supply.

Huawei apparently has a ‘Plan B’ which would make it, in turn, less reliant on American components, and then we are looking at a world of diverging, rather than converging, technology and all the issues of compatibility, and beyond, that creates, eventually leading to “digital Balkanisation” as Diane Coyle, economics of technology expert at Cambridge University, put it.

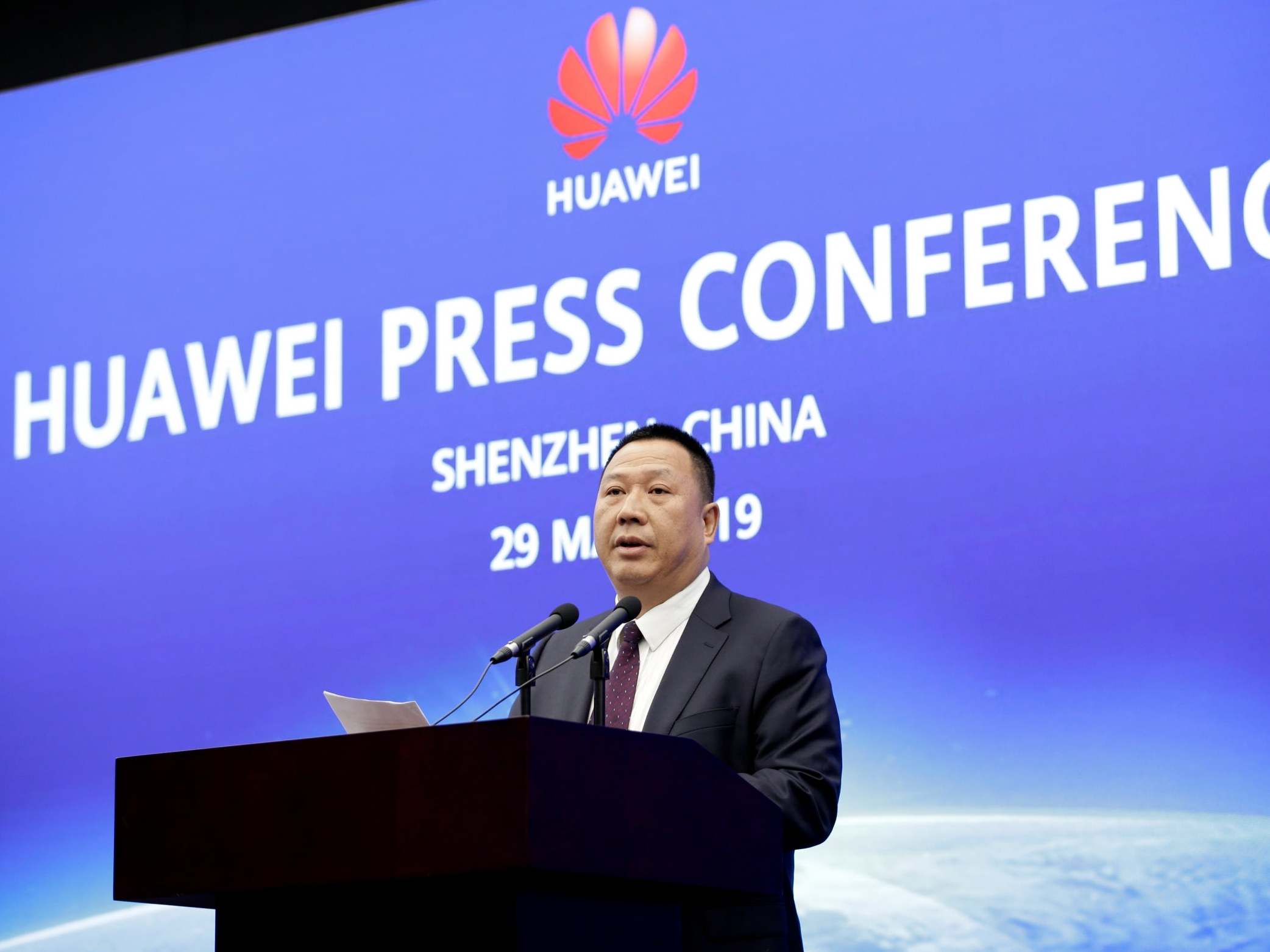

And, more to the point, if Trump is successful with Huawei, who or what will be next in his firing line? As Song Liuping, Huawei’s chief legal officer has argued, the US has not provided any evidence to show Huawei is a security threat: “There is no gun, no smoke, only speculation,” he said. He has also accused the US of setting a “dangerous precedent. Today it’s telecoms and Huawei. Tomorrow it could be your industry, your company, your consumers.”

Other squabbles, it seems, lie ahead. The US is still in dispute with China over its expansionism in the South China Sea, so Trump will clutch at any opening. Huawei, as many have pointed out, is just one strand of Trump’s attempts to ensure that the US, rather than China, emerges as the global superpower in the decades ahead. Let it not be forgotten that it was Trump who described climate change as a Chinese-perpetuated hoax.

African swine fever has cut a swathe through China’s huge pig population this year – pork being one of China’s main protein sources – and any leverage, however small, will be grasped in the trade war the current US administration seems set on waging. Trump might not be so astute as to have noticed that the price of pork is set to rise, but his advisers assuredly will have.

Of course, Trump can change course at the drop of a hat. In an earlier trade spat with Chinese technology company ZTE, the US banned companies from trading with it. One month later Trump announced he had personally intervened with Chinese premier Xi Jinping to lift the sanctions. Perhaps he sees Huawei as an even bigger bargaining chip? That may be, but many analysts see further discord ahead with AI possibly forming the next battleground. Whatever the case, China (like Trump) will fiercely defend its own markets and interests.

And, of course, this week he appeared to back down over trade tariffs on Mexico, with which he threatened to implement 5 per cent duties, rising every month, on imports unless the Central American country acted to curb migration. The US and Mexico struck a deal on immigration and trade but a few days later Trump bluntly suggested the US might again seek to impose punishing tariffs if the neighbouring country doesn’t toe the line.

It is said that trade wars benefit no one. That is not necessarily true, but the beneficiaries tend to be few and almost never those at the bottom of the manufacturing chain such as workers and consumers. Victories are limited and often pyrrhic. And this one has yet to play out to its full extent, whatever is or isn’t hidden inside Huawei’s 5G infrastructure.

In the end, beyond the politics, Trump’s beef with Huawei boils down to a couple of simple, commonsense propositions. And both seemingly confirm that, bombastic trade battles aside, Trump’s actions are either terribly futile or distrustful fantasy.

It is true that Huawei’s 5G designers could build in technology that can spy on Britain, or the US, or whomever. And yes, the west probably could take security steps to try to stop it. But why would Britain, or anybody else, bother to take the risk?

But then you could turn that first proposition right on its head. There would be no risk because it would be insane for Huawei to jeopardise its business, its reputation and the livelihoods of its employees (especially if they are effectively Chinese state workers) on trying to bug the world. Especially when they know the world will be looking for it.

There are, right now, as our anonymous cyberfacilitator pointed out, too many ifs and too many buts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments