‘Despacito’ is the most streamed track on earth. How have music formats changed since the first recording in 1860?

From the metal cylinder used to create the first recorded track, through vinyl, iPods and now the ephemeral streaming experience, music fans often don’t know what they’ve got ’til it’s gone

How long has it been between the very first recorded song and the day that a song became the most streamed track on earth? A little over 150 years.

The most streamed track is, of course, Despacito, the Spanish-language track by Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee, featuring Justin Bieber. It has been listened to via streaming a whopping 4.3 billion times, 93 million of those in the UK… half as many times again as the population.

That first song recording took place on 9 April 1860, carried out by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville on a cylinder; a woman singing the old French folk song Au Clair de la Lune.

Aside from both being music – and, perhaps, non English language – it might be that they have little else in common. But just maybe they are bookends of our relatively slight, in terms of the history of the human race, ability to keep a permanent record of our music.

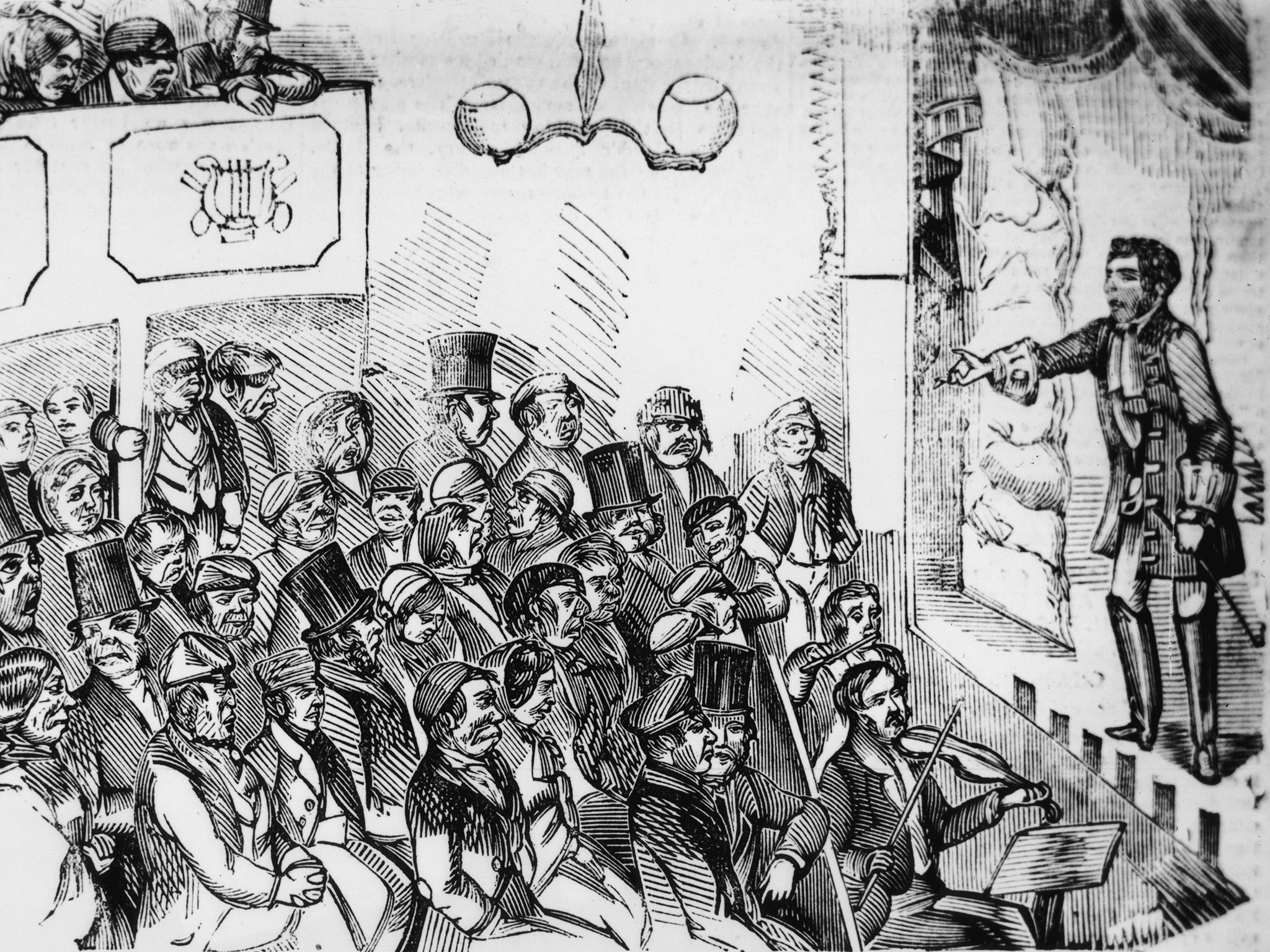

Before Au Clair de la Lune, music had to be heard live to appreciate it, in the concert halls or the drinking dens, whether chamber orchestras or drunken sea shanties. And after Despacito… well, those 4.3 billion streams of that song are as ethereal and ephemeral as the oral tradition of music, played once and then lost in time, like tears in the rain, to quote a phrase.

As I listen to music on Spotify, or YouTube, or Apple Music, or any other streaming service, I am often struck by the rather bleak thought that all it would take would be for someone to switch off the internet – Isis, perhaps, or aliens, or Donald Trump’s finger inadvisedly hovering over some red button – and that would be it for a huge proportion of the population. No more music.

Of course, it doesn’t have to take something of such apocalyptic proportions. I was put in mind of the scenario again recently by a piece in the New York Times, in which writer Ansel Elgort detailed a road trip embarked upon by a group of millennial friends across Mexico. They found themselves far from any mobile phone signal, and their internet-powered supply of music via streaming services died slowly (or “despacito”, perhaps). One of their number came to the rescue with an old iPod, stuffed with music, that saved the trip… at least until their phones found a signal again.

What emerged from Elgort’s piece is that the generation for whom streaming music is the norm are starting to feel nostalgic about MP3 players, in the same way that older generations looked back on the days of vinyl with a misty-eyed sigh.

In fact, 21-year-old New Yorker Connor Gressitt, the guy who had the iPod on that road trip, uses it so much it’s acquired an almost hipsterish cool. “I definitely get odd looks,” he told Elgort. “I was using it on the subway two weeks ago, and someone my age asked me, ‘Is that, like, an iPod?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, dude.’ I get weird looks, but people are stoked, actually, because most everyone had an iPod at one point of their lives.”

If you’re my age, which falls into the Generation X category, sandwiched between the millennials and the baby boomers born in the wake of the Second World War, you’ll have similar fond memories of vinyl and perhaps even compact discs.

When I was growing up, aside from the radio there was only one way to listen to an album, and that was on a 12-inch black disc. Oh, you could by albums and even singles on tape cassette, of course, but who did that? Not when you could tape from the record yourself, despite all the exhortations for us not to do so.

Home taping is killing music, we were told. But we did it anyway, and it didn’t. Besides, how else were you supposed to take your music with you in the car? You couldn’t very well set up your record player on the back seat. An album fitted very snugly on one side of a C90 cassette, and then of course there was the joy of the mixtape… singles, album tracks, rarities, B-sides, all lovingly and painstakingly assembled for a unique listening experience, or to give to a member of the opposite sex who had caught your eye in a very 70s/80s mating ritual that showed your cool credentials as much as a peacock fanning his tail feathers.

No one could conceive of the situation changing, until they went and invented the compact disc, and in the mid-1980s everything we thought we knew was wiped away. I remember my first CD player… it was what we charmingly called a “ghetto blaster”, a squat, black plastic thing that was designed, presumably, for listening to hip-hop on while doing some break-dancing on a street corner in Detroit. I used it for listening to the first two CDs I bought; Guns ’n’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction and Bon Jovi’s Slippery When Wet (don’t judge me; it was a phase I was going through. This must have been 1987 and my music taste improved immeasurably the following year when I went to college).

CDs were smaller, easier to store than vinyl LPs, and were fabulously futuristic-looking, with their shiny discs and jewel-cases which could hold booklets-full of lyrics and information. Eventually, we could even get cars that played CDs, doing away with the need for home taping at all, though with CDs even taping was a joy… you didn’t have to pause the tape halfway through to turn the record over.

My first foray into digital music didn’t come until maybe 2001 or 2002, when my wife bought me an iPod, second generation I think. It was white and chunky and showed only the name of the track on a monochrome screen, but what witchcraft was this? What seemed like an almost limitless capacity for music, and the shuffle function meant that even the tried and trusted old mixtape was redundant… I could have a different playlist every single time I turned the thing on! It was musical heaven in a little white box.

The thing with advances in music is, we don’t have time or inclination to mourn the passing of one format because we’re too caught up in the white heat of new technology. I happily tossed my vinyl to one side when I bought my first CDs; when I got the iPod my CDs seemed very quaint and 20th century. I don’t even remember when I downloaded Spotify on to my iPhone, but suddenly it seems to be the only way anyone listens to music in our house any more, especially our children, aged 14 and 12, who I don’t even think recall any other way.

It seems to be that as each advance in technology creeps towards its end, we get nostalgic about the past. When CDs had taken firm hold, people began to remember vinyl and all those qualities that had made it obsolete – the hiss of the needle as it hit the grooves, the need to manually turn it over, the large, cumbersome sleeves – suddenly became things to cherish. Go into the home of anyone who had their youth or twenties in the 1990s and you’ll see racks and racks of CDs, probably held in something specially designed for that exact purpose by Ikea. And now young people are getting the same feelings about iPods and MP3s.

Why? Possibly because all those formats represented ownership of music, rather than streaming, which is just a transitory experience. If MP3s sucked the soul out of collecting music, at least you still owned that digital file. Now music is yours purely for the duration it takes to listen to.

Or possibly because, Despacito and its 4.3 billion streams aside, the current way of listening to music is already on the wane. We can generally never imagine any other way of consuming music than the one we’re doing right now, but somebody, somewhere will be on to it.

I googled “how will we listen to music in the future”, and got all manner of results. But one interesting one leapt out, and it’s called Subpac. It’s essentially a vest fitted with speaker technology, so you don’t just listen to music, you feel it as well. Here’s the actual science bit: “Subpac transfers low frequencies directly to your body and provides you with a new physical dimension to the music experience. Feel the boom of a kick drum, the warmth of an 808, and the richness of soundscapes in the comfort of your own studio, home, coffee shop, or wherever you go.”

Indeed. Not only do we not need to be bothered by other people any more when we listen to music, thanks to advances in headphone technology, now we don’t even need to go to a club or gig any more.

Who knows what Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville would have made of all this when he made that first song recording. We’ll never know, but one thing we can do is listen on YouTube to the actual recording he made in 1860 of Au Clair de la Lune. The actual thing.

Because, despite what you might have surmised from everything you’ve just read… ain’t technology wonderful?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks