Heathcliff's missing years: Author tells the untold tale from ‘Wuthering Heights’

Like the spirit of Cathy, the ghosts of the Brontës have been tapping at writer Michael Stewart’s bedroom window. David Barnett talks to the man who made it his mission to chart the disappearance and return of one of literature’s most fascinating antiheroes

Writers are known to go to great lengths in the name of research, but few have gone as far as Michael Stewart; 65 miles, on foot, from the moors above Haworth in West Yorkshire to the city of Liverpool on the west coast.

Stewart undertook the three-day journey as part of his bid to understand a literary mystery that has niggled at him for more than two decades… and which now forms the basis of his astonishing novel, Ill Will.

That selfsame journey was carried out on the page at the behest of another writer, more than 170 years ago: Emily Brontë, in her only published novel Wuthering Heights, in which Mr Earnshaw, the master of the titular house up on the wiley, windy moors in Yorkshire’s West Riding, takes himself off to Liverpool… and returns with Heathcliff, who has become one of the most fascinating and instantly recognisable antiheroes in literature.

Stewart, 47, has been mildly obsessed with Wuthering Heights since he was a boy, but not through any particularly precociousness in reading… like many of us, he was introduced to the novel via the 1978 song by Kate Bush.

“I was seven at the time, and I was instantly struck by that song,” he says. “It was everywhere, it was at the top of the charts, it was all over the TV. I went over the lyrics repeatedly in my head. I didn’t really understand them, especially the lines about Cathy at the window… where was she? Why wasn’t she using the door?”

Kate Bush, of course, took her imagery from the opening chapters of the 1847 novel, in which Mr Lockwood rents Thrushcross Grange from Heathcliff, and while visiting his landlord at the remote farmhouse Wuthering Heights, has a vision of the ghostly Cathy, pleading to be let in at the bedchamber window. Back in his rented accommodation of Thrushcross Grange, Lockwood is told the strange history of Wuthering Heights by the housekeeper, Nelly Dean.

Stewart found his own Nelly in his mother. Having left school early, she was making up for it while Stewart was young by taking her English O-level at night school in Salford, Greater Manchester, where they lived. And coincidentally enough, at the time of Kate Bush’s hit, she was studying Wuthering Heights.

“Just like Nelly tells the story to Lockwood, my mother told it to me,” says Stewart. “It actually comes across really well as an oral tale. So from a very young age, I knew the story quite well, though I didn’t read it properly myself until my early twenties.”

Stewart moved over the Pennines in 1995 when he enrolled as a mature student at the University of Leeds, and stayed in Yorkshire. For many years he has now lived in the village of Thornton, actually right across the road from the house in which the Brontë sisters were born, before their father, Patrick, took them to Haworth when he took up his job as minister of the village, living in the now-famous parsonage.

Perhaps, like the unique spirit of Cathy, the ghosts of the Brontës were tapping at Stewart’s bedroom window, because the seed of an idea lodged in his mind and refused to be budged. The more prosaic explanation is that the notion was sparked when Stewart read the literary critic John Sutherland’s essay Is Heathcliff A Murderer?, in which the question was posed as to how Heathcliff went from being a humble stableboy brought home from Liverpool by Mr Earnshaw to being, in Sutherland’s words, “a gentleman psychopath”.

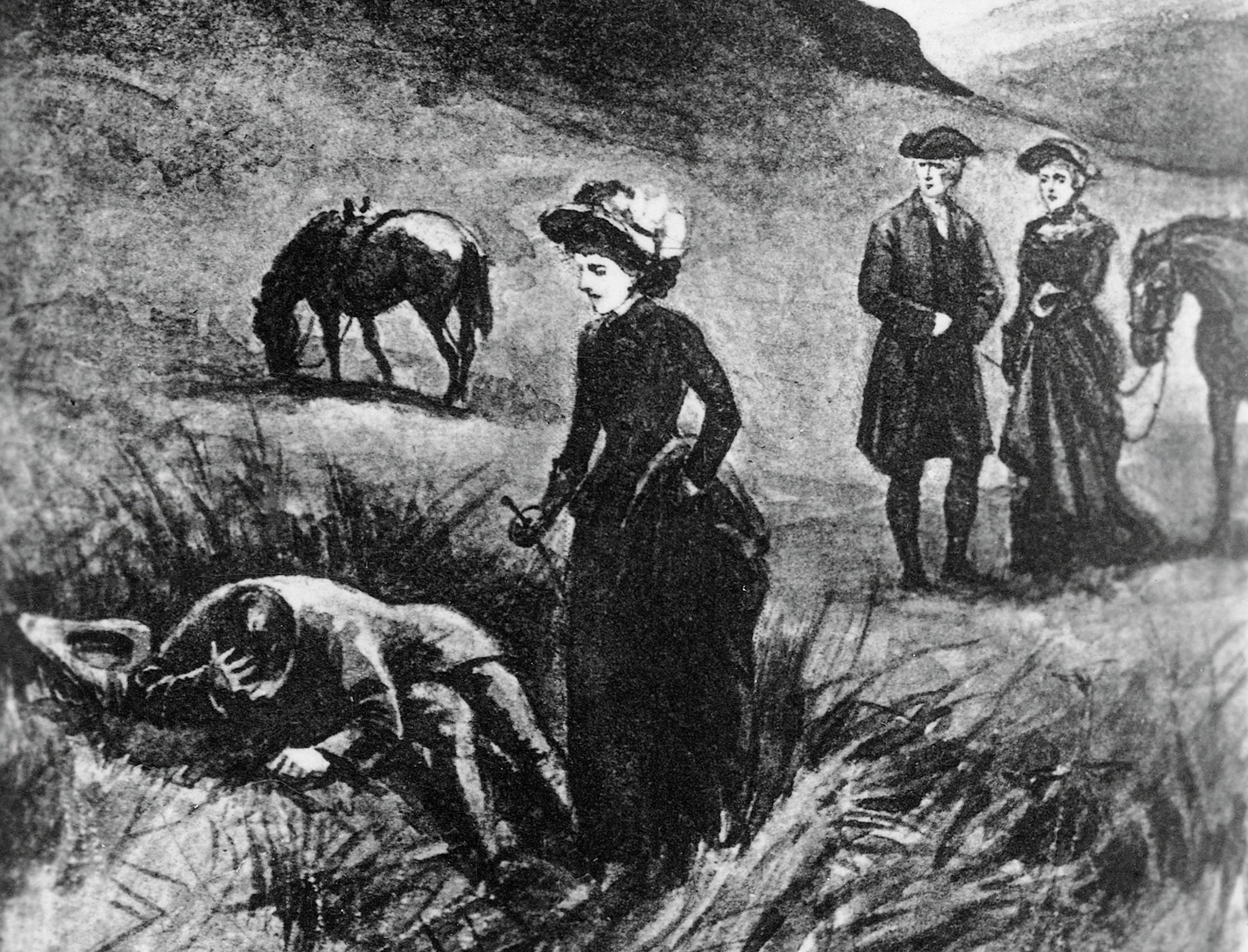

In the original novel, Catherine, though she loves Heathcliff with a burning intensity, marries her social equal Edgar Linton. It is a sacrifice; she hopes her marriage will enable her to raise Heathcliff’s lot in life. But overhearing of her plans to marry, Heathcliff flees Wuthering Heights.

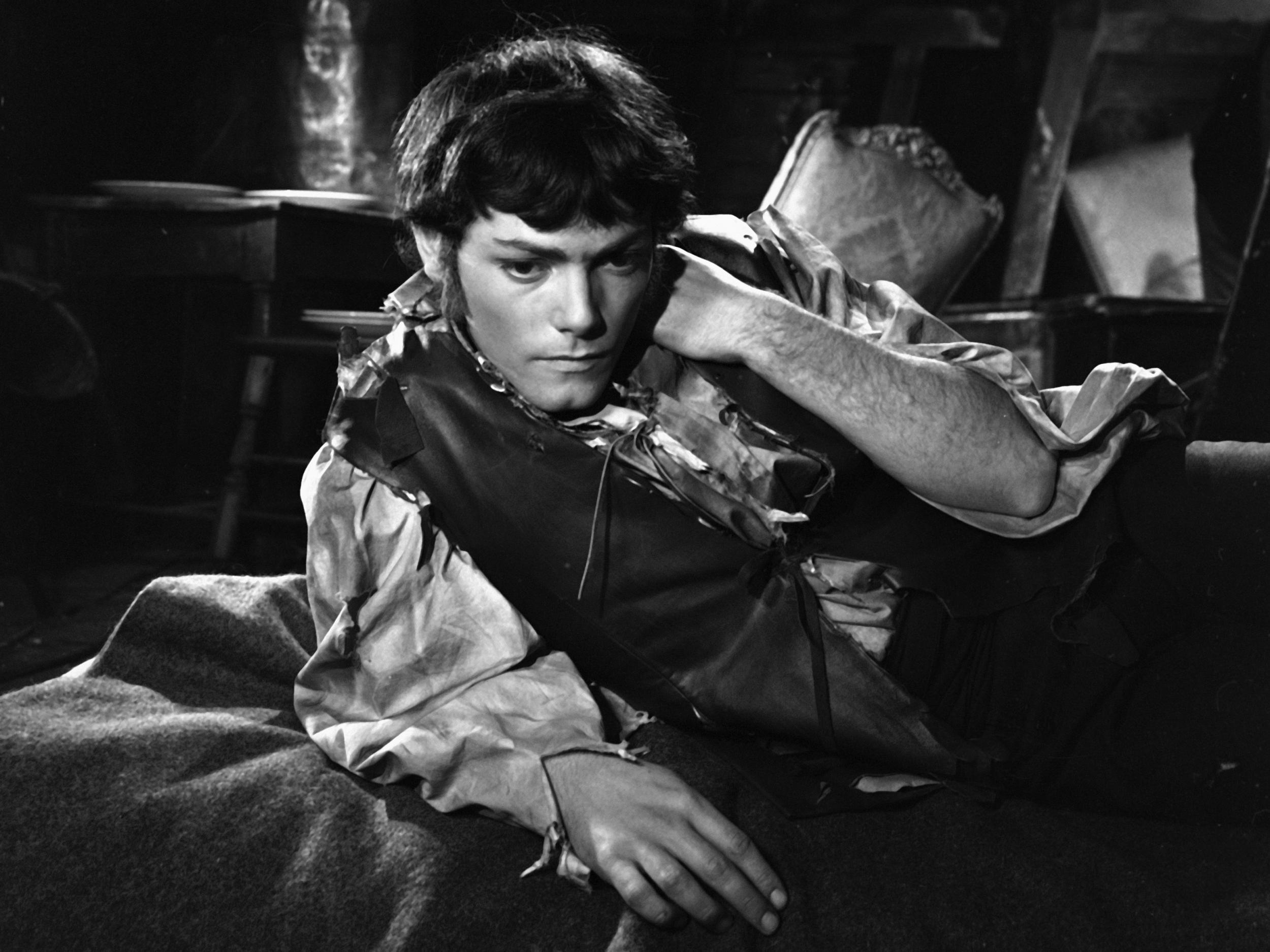

And he is gone for three years. When he returns, he is a man of means, wealthy and well dressed, though still wild at heart and with a blazing passion and a foul temper. He will eventually take possession of both Thrushcross Grange and Wuthering Heights. But where has he been in those three years? And how did he make his fortune?

There are no real clues in Emily Brontë’s novel, and it is Stewart’s work, Ill Will, that sets out to answer that question. Thus he has Heathcliff setting out to return to Liverpool, from where he was taken by Mr Earnshaw, in a bid to discover the truth of his own origins.

On the way he meets a young woman, Emily, the daughter of a highwayman, who can claim to talk with the dead. Like an 18th-century Bonnie and Clyde, with extra-fruity language for good measure, they range over the north of England, pulling off schemes and scams and sending Heathcliff inexorably to his destiny and the pot of cash which will allow him to return to Wuthering Heights a new man. But before he gets there, he will have to do something terrible…

“Once I’d got the idea I wrote the first chapter straight away,” says Stewart. “But then I realised I knew next to nothing about the 18th century; I’m not a historian and I hadn’t even read a great deal of historical fiction. And I knew I had to get this right.”

Which is where the idea to retrace Mr Earnshaw’s steps from Haworth to Liverpool came in. There was something about that which bothered Stewart from the off. “Earnshaw was a farmer, so why would he take time off at the busiest time of the year to go to Liverpool? And why did he go on foot? There was a carriage from Keighley to Liverpool, and we know from the novel he had two horses. The only thing I could think of was that he was travelling incognito.

“But why would his mission be a secret? It was then that I realised that at that time Liverpool was one of the biggest slave ports in Europe. Was Earnshaw going to procure a slave to work on his farm?”

Although most film adaptations of the Emily Brontë novel, until Andrea Arnold’s 2011 movie, have used white actors to portray Heathcliff, he is described variously as a Lascar (an Indian sailor), as “a black” by Nelly Dean, and as “a dark-skinned gypsy in aspect”.

Stewart says: “Heathcliff’s ethnicity was never directly addressed in the book, but it is obvious looking back that he was black, and possibly a slave, or the child of slaves. And this was an important time as slavery was becoming frowned upon and there was a growing movement to have it banned. Slavery was rife, even in Yorkshire, and often they were just called ‘servants’ rather than slaves, of course.”

Indeed, it was only in 2013 that the extent to which Britain’s stately homes were bought or built with money directly from the proceeds of the slave trade was revealed; something that for many years most people either didn’t know about or wilfully ignored. “Slavery was a well-kept secret for a long time,” says Stewart.

Having borrowed from Emily Brontë for his latest novel – though obviously filling in a huge hole in the original narrative – Stewart is now giving something back to the literary dynasty and their legions of fans who beat a path to Haworth all year round. He is heading up the Brontë Stones initiative, which has secured funding from the Arts Council and Bradford Council to create a walk up on the moors above the sisters’ home village, guided by marker stones commemorating the Emily, Anne and Charlotte, and their wayward brother Branwell. The initiative has been on the drawing board since 2016 and is speeding up towards fruition.

The route will take walkers from Thornton, where Stewart lives and where the sisters were born, up to the moors above Haworth, and the sites of important locations in their stories, including of course Wuthering Heights.

The stones will become a permanent reminder of the Brontës, in the landscape that made them the women they were and gave them the grit and determination to become published authors at a time when the very idea was so scandalous that they had to use male pen names. It’s the same landscape that has fascinated Stewart for the past two decades, and even before, as a boy on the other side of the Pennines, when Kate Bush raised so many questions in his young mind.

At least now, thanks to his writing of Ill Will, Stewart has answered at least one of those vexing questions; the whereabouts of Heathcliff during his three-year disappearance. While Cathy might be forever tapping at the window, Stewart has laid one ghost to rest.

‘Ill Will’ by Michael Stewart is published by HarperCollins HQ and is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks