The century-old German dictionary still being written

It has seen the fall of an empire, two world wars and the division and reunification of Germany, and they’re still only up to the letter R, writes Annalisa Quinn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When German researchers began working on a new Latin dictionary in the 1890s, they thought they might finish in 15 or 20 years.

In the 125 years since, the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (TLL) has seen the fall of an empire, two world wars and the division and reunification of Germany. In the meantime, they are up to the letter R.

This is not for lack of effort. Most dictionaries focus on the most prominent or recent meaning of a word; this one aims to show every single way anyone ever used it, from the earliest Latin inscriptions in the sixth century BC to around AD600. The dictionary’s founder, Eduard Wölfflin, who died in 1908, described entries in the TLL not as definitions, but as “biographies” of words.

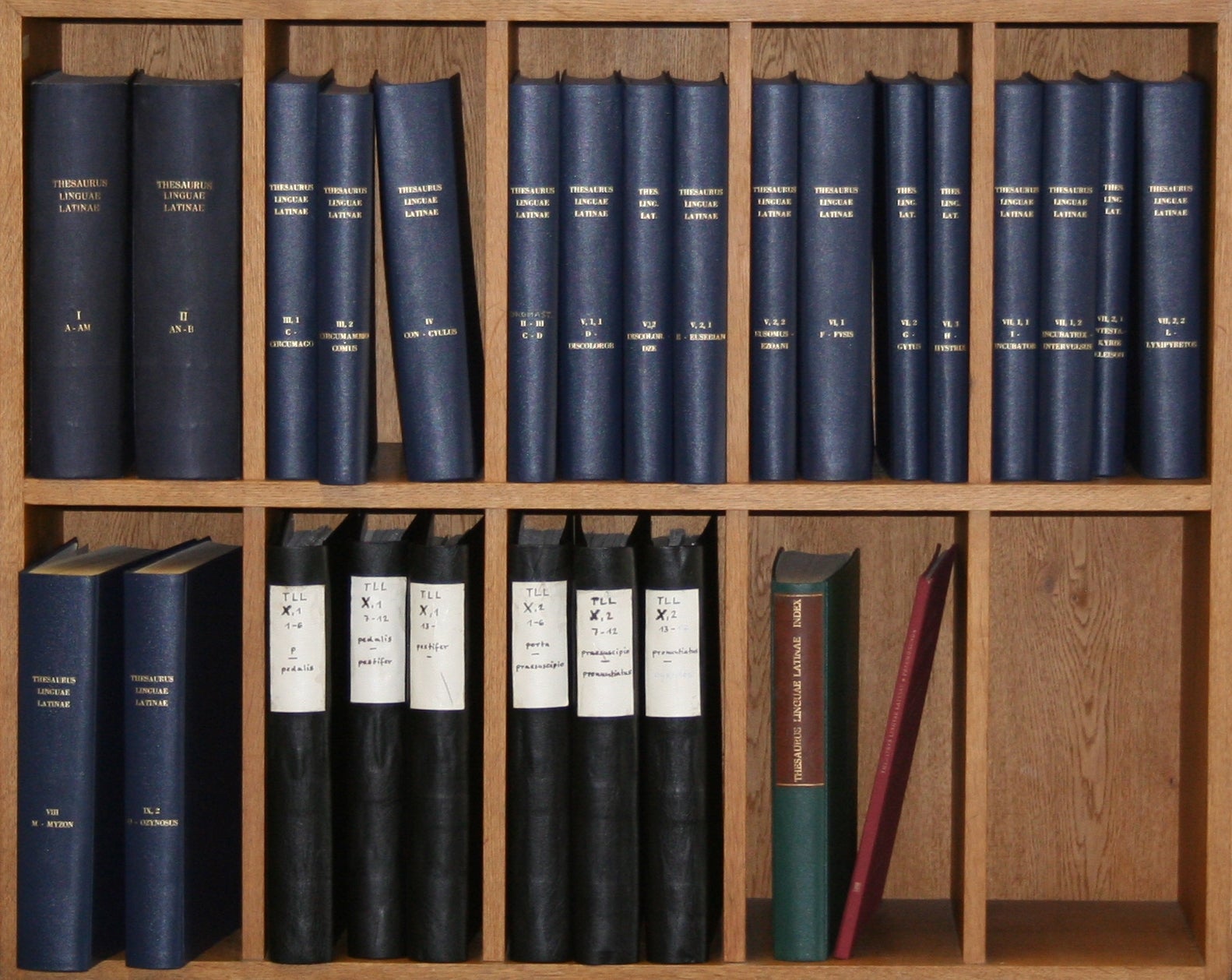

The first entry, for the letter A, was published in 1900. The TLL is expected to reach its final word – “zythum”, an Egyptian beer – by 2050. A scholarly project of painstaking exactness and glacial speed, it has so far produced 18 volumes of huge pages with tiny text, the collective work of nearly 400 scholars, many of them long since dead. The letters Q and N were set aside, because they begin too many difficult words, so researchers will have to go back and work on those, too.

“Its scale is prodigious,” says David Butterfield, a senior lecturer in classics at Cambridge, adding that when the first publication appeared in 1900, “it did not go unnoticed that the word closing that instalment was ‘absurdus’”.

It’s a monumental effort aimed at a small group of classicists, for whom the ability to understand every way a word was used is important not only for reading literature, but also understanding language and history.

Once the language of a vast physical empire, then a vast spiritual one, Latin is now spoken mostly within the walls of the Vatican and among a handful of “living Latin” enthusiasts, who promote speaking the language as an educational tool.

In the United States, Latin education dropped off sharply through the 1970s, but it has held steady in recent decades. About 210,000 public school students are learning the language (slightly fewer than are learning Chinese, and a tiny fraction of the 7.3 million in Spanish classes), according to Sherri Halloran, a spokeswoman for the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

But because it was Europe’s primary literary language for more than a thousand years, Latin is “the key for a considerable piece of human history”, says Michael Hillen, the project’s director.

But because it was Europe’s primary literary language for over a thousand years, Latin is ‘the key for a considerable piece of human history,’

Around half of English words are also derived directly or indirectly from Latin. (We also, of course, use intact phrases such as “quid pro quo”, a theme of the recent impeachment hearings. It means “this for that”.)

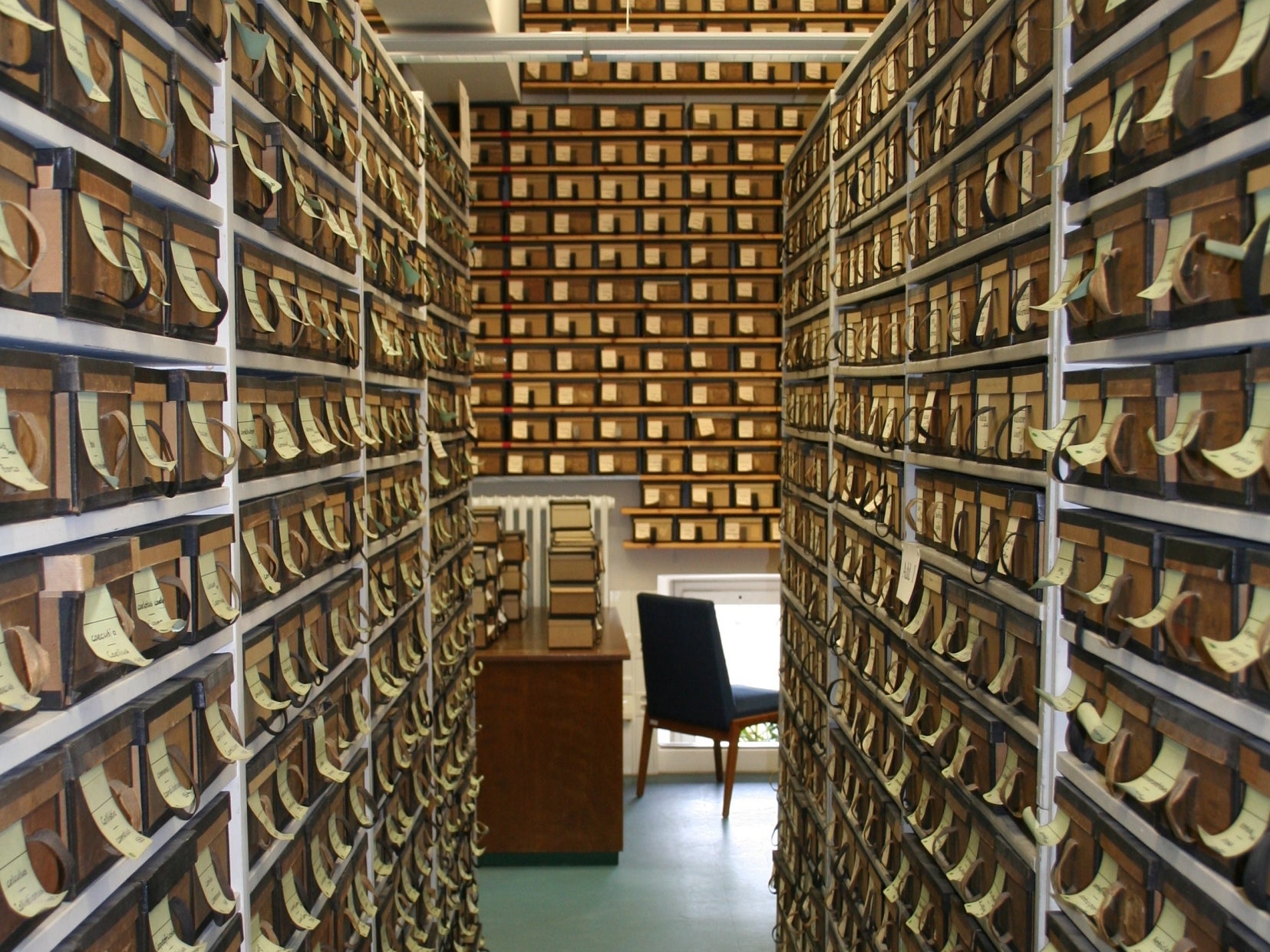

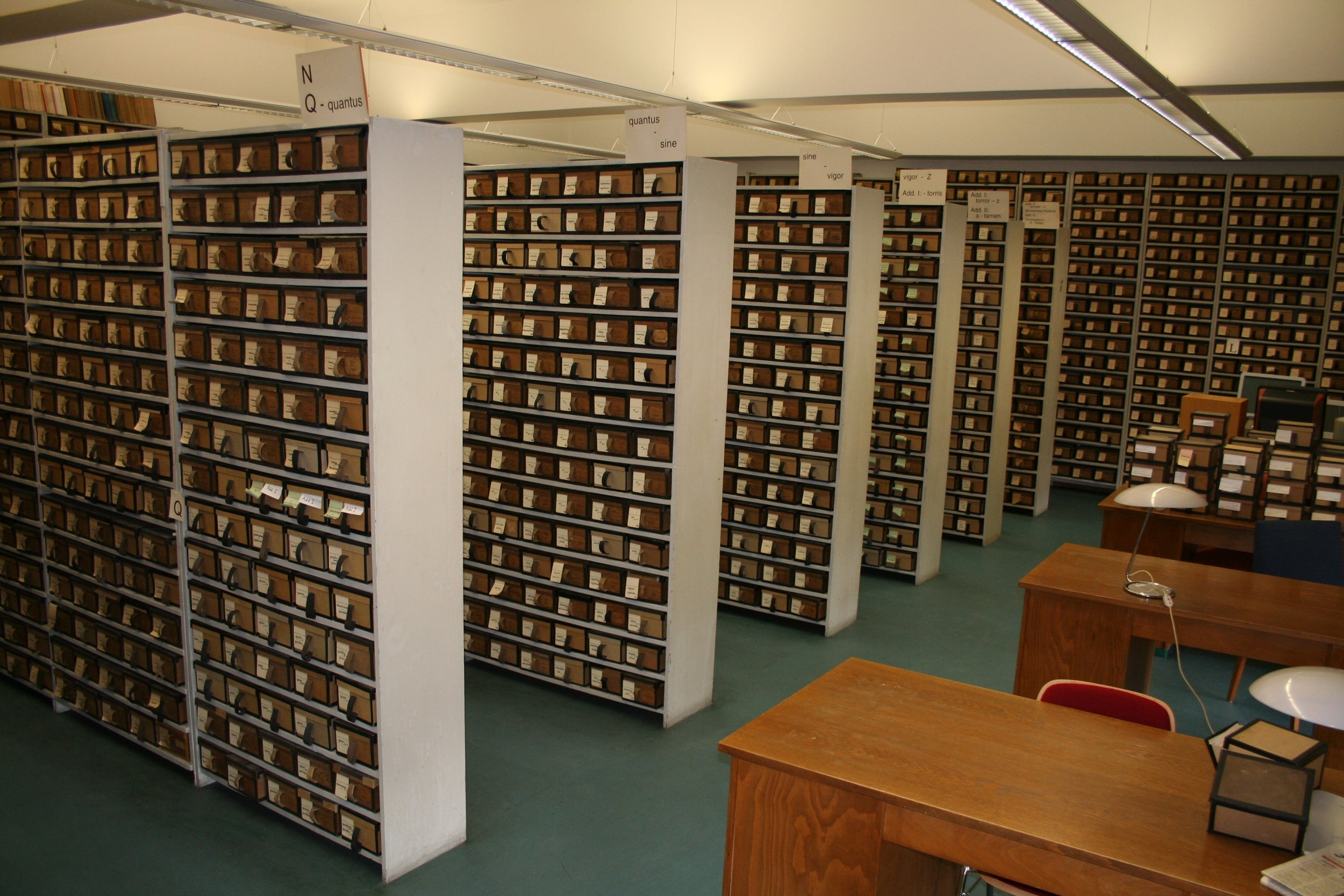

The poet and classicist AE Housman, who died in 1936, once referred to “the chaingangs working at the dictionary in the ergastulum [dungeon] at Munich”, but the TLL is now housed in two sunny floors of a former palace. Sixteen full-time staffers and some visiting lexicographers work in offices and a library, which contains editions of all the surviving Latin texts from before AD600, and about 10 million yellowing paper slips, arranged in stacks of boxes reaching to the ceiling.

These slips form the heart of the project. There is a piece of paper for every surviving piece of writing from the classical period. The words, arranged chronologically, are given in context: they come from poems, prose, recipes, medical texts, receipts, dirty jokes, graffiti, inscriptions, and anything else that survived the vicissitudes of the last 2,000 years.

Most Latin students read from the same rarefied canon without much contact with how the language was used in everyday life. But the TLL insists that the anonymous person who insulted an enemy with graffiti on a wall in Pompeii is as valuable a witness to the meaning of a Latin word as a poet or emperor (“Phileros spado” reads one barb, or “Phileros is a eunuch”).

Reading these texts creates “respect, empathy, and understanding – which doesn’t mean condoning the things they did”, says Kathleen Coleman, a member of the board overseeing the dictionary’s progress. “We don’t have to think gladiators were a great idea. But to try and understand what they were getting at. What they thought. Why they thought what they were doing was right. And you get that kind of depth from language.”

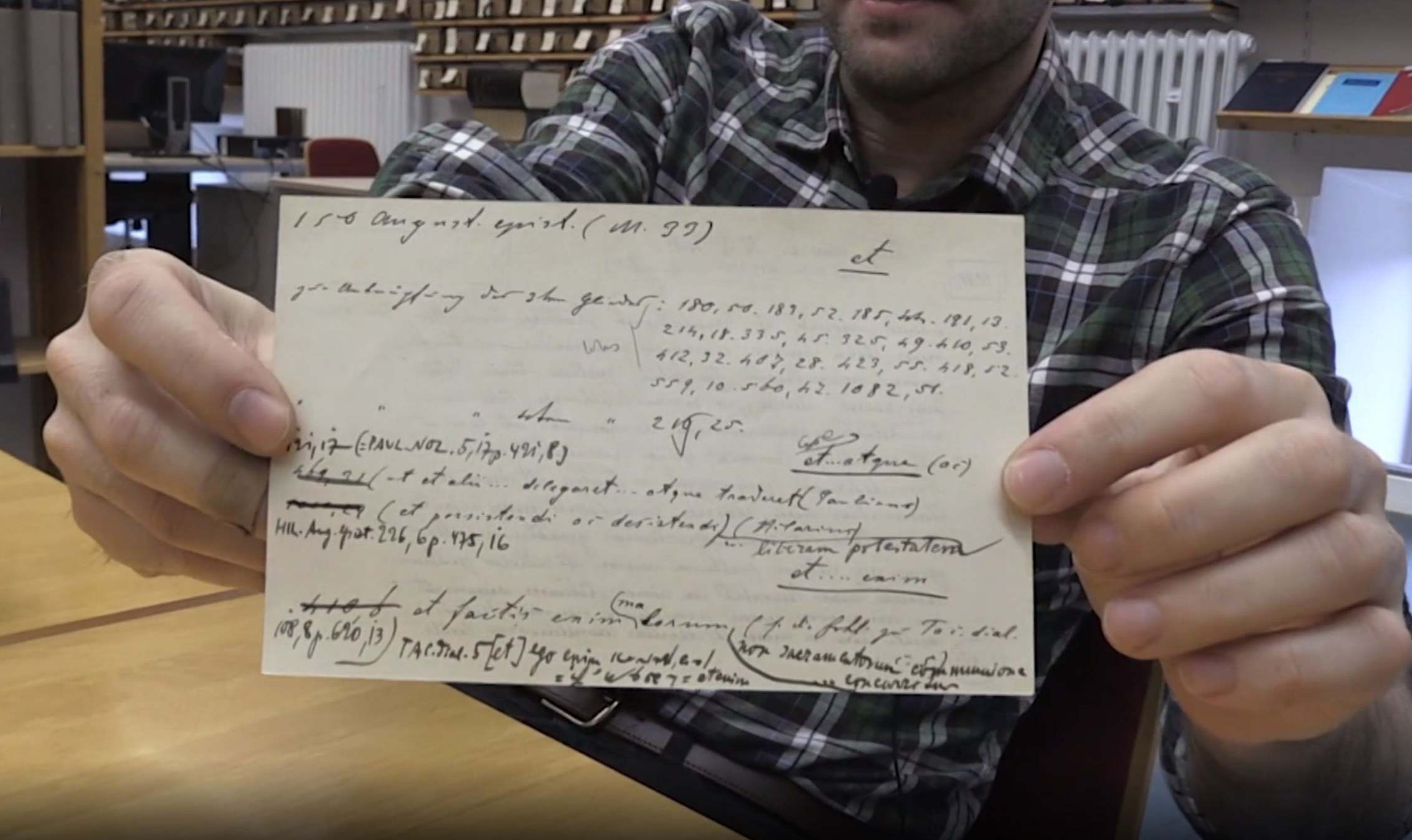

About 90,000 of the slips represent uses of the word “et”. In order to grasp every possible shade of the word’s meaning, the researcher who wrote the entry read each of the passages in which it occurred and sorted them into categories of usage, like a scientist cataloguing specimens. It took years.

“Et”, an apparently simple word that usually means “and”, can also mean a range of slightly different things, including “even”, “and also”, “and then”, “and moreover”, et cetera.

“You have to know about all kinds of texts: Roman law and medicine and poetry and prose and history,” says Marijke Ottink, an editor at the TLL. She has been working on the word “res”, meaning “thing”, on and off for a decade.

Visiting researchers often come to look into particular words – the guest book outside the library contains, in faint letters, the name Joseph Ratzinger, better known as Pope Benedict XVI. He came to consult the boxes for “populus”, which means “masses” or “people”.

Some assignments are more coveted than others: Josine Schrickx, an editor, says she would like to write the entry for the word “thesaurus”. In Latin, it means “treasury”.

Some assignments are more coveted than others: Josine Schrickx, an editor, says she would like to write the entry for the word ‘thesaurus’. In Latin, it means ‘treasury’

On the horizon, however, is “non”, which means “no”. With nearly 50,000 slips, it is a source of anxiety at the TLL. “I don’t know how to deal with a word on that scale,” says Adam Gitner, a researcher. “And that does frighten me.”

The complicated conjunction and adverb “ut” also looms. Butterfield said that it is “the sort of infernal business that would make Sisyphus and Ixion smile kindly on the job satisfaction they got from their daily toil”, referring to figures from classical mythology forced to labour in pain for eternity

The dictionary is not only difficult to produce, but also to use. Written in Latin, entries are made up of “dense print in numbered columns, subdivided by capital Roman numerals, then capital letters, then Arabic numerals, then perhaps more Arabic numerals, then lowercase letters, then – if you’re still on the trail – Greek letters”, says Butterfield. But the difficulty in using the TLL is “an essential hurdle of scholarship”, he adds; it is “a tool that is without parallel in understanding how Latin was deployed”.

It is also expensive: an online version costs $379 (£289) for individual yearly access. Many universities have subscriptions, but to improve access, this year the TLL posted PDFs of entries through the letter P for free online.

The TLL has survived a chaotic century: a significant portion of its staff died in combat at the beginning of the First World War. During the Second, the slips were moved to a monastery to escape the bombing of Munich. In response to postwar nuclear fears, they were copied onto microfilm, which was placed in a bunker below the Black Forest, where it remains, alongside other culturally significant work.

Originally a German state undertaking, the project became international after the Second World War. Its €1.25m (£1.06m) annual budget still mostly comes from German taxpayers, but international partners, including the United States, send researchers to Munich.

Judging by the accuracy of previous estimates, the 2050 end date may be optimistic. Many of the researchers at the dictionary say they don’t expect to live to see it finished.

But Christian Flow, a visiting assistant professor at Mississippi State University who wrote a dissertation about the TLL, says that its duration is also its strength. “The irony is that the timelessness of the thesaurus,” he says, “lies in its inability to finish itself.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments