Do the middle-aged Generation X really have it as good as we think?

They got the best education, the best jobs, the best houses, and pulled the ladder up behind them, says David Barnett. But is it really as good as it looks?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Can there be a more lightly disparaging term than to be branded “middle-aged”? Oh, to be damned to that most boring and bland circle of hell, that wasteland of life, those wilderness years, that mass of humanity which does nothing but is blamed for everything.

When you’re middle-aged, we’re told, your vibrant, creative, revolutionary years are behind you. It’s just a trudge through endless days of work and toil, driving sensible cars, perhaps rearing children who don’t understand you and whom you don’t understand. The golden haze of retirement, coach trips, guaranteed life insurance (with a free pen just for applying!) and bespoke conservatory blinds are still a distant dream.

The middle-aged are boring. The middle-aged are privileged. The middle-aged have broken the world, and resent the young for trying to fix it. The middle-aged got the best education, the best jobs, the best houses, and pulled the ladder up behind them. Not only are they sticking two fingers up to the generation that follows them, they’re doing the same to the older generation, putting them in care homes and refusing to visit, save for grudgingly having them round at Christmas.

What can be duller than the middle? The middle is sitting on the fence. The middle is No Man’s Land. The middle is not one thing, nor the other. The middle is your Centrist Dad and Mondeo Man and sharing your organic recipes on Mumsnet.

It all sounds jolly awful, I think. Imagine being middle-aged. Imagine being assimilated into this Borg-like mass of joyless existence. Imagine being one of those people. Then I catch sight of myself in the mirror, or have to scroll endlessly through some drop-down menu to find my impossibly distant birth-year, or find myself telling a younger person what life was like when there were only three channels on the TV.

“Do they mean us?” I say in my best Derek Jameson impression. “They surely do!” And then the realisation is compounded by the fact that I have to explain to some callow youth who Derek Jameson was. Because there doesn’t appear to be any getting away from it: I am middle-aged.

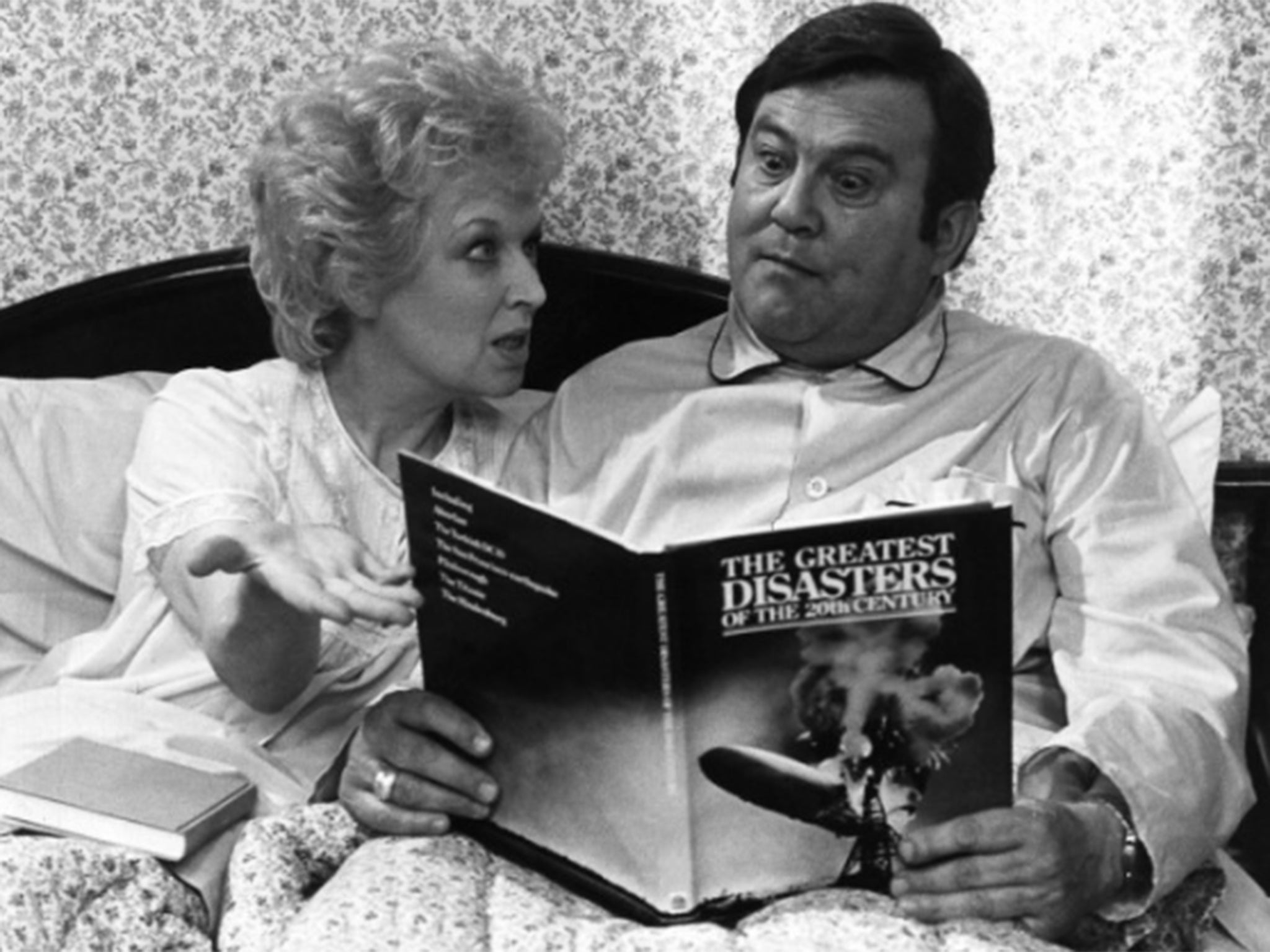

And yet… what exactly do we mean by that? What is middle-aged? When I think of middle-aged, here is the collage of images that flurries in my mind: Terry and June. Knitted cardigans with those thick, round buttons with a cross on them. Getting a bad back. Getting involved in petitions about driving roads across fields or building houses where they’re not wanted. Being unable to find a pair of denim jeans that suits you. Acquiring a job title with brackets in it somewhere. Having a mid-life crisis. Buying a sports car. Investing money. Cultivating a stomach that’s got a greater circumference than your chest. Hearing the word “prostate” from your doctor for the first time.

It’s almost like a more sedate version of Renton’s “Choose Life” speech from Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting.

But though I barely recognise those things, I am inescapably middle-aged. I am of the demographic cohort Generation X, which was born, according to most measures, from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s. Once you are supplanted by a younger demographic, as Generation X has been by the millennials (born roughly 1982 to 2002), then you hand over the baton of the younger generation and must necessarily slide into middle age.

So, is middle age just a number, then? If so, what number? I asked Twitter by way of a poll what constituted middle age. The overwhelming consensus (56 per cent of respondents) was that not only does life begin at 40, but middle age does as well. However, 30 per cent (presumably made up of people like me in their 40s) thought that middle age began at the age of 50. A few optimistic souls (8 per cent) said that it started at the age of 60, while 6 per cent actually thought you were middle-aged when you hit 30.

Still, said in the manner of a leering uncle at a wedding reception, you’re only as young as you feel, right? And whichever way you slice that, it means that certainly the earlier millennials are slouching towards middle age, if they haven’t got there already.

But, ultimately, what does any of this matter anyway? Well, in terms of how old we are and how old we feel, perhaps it doesn’t. But there are wider social repercussions to the idea of middle age. On the one hand, it’s maybe not the first-class ride on the gravy train that millennials think it is.

In fact, it’s possibly one of the most financially fraught periods of life. The Alliance Savings Trust released a study this week after surveying 1,000 45-55-year-olds about their economic situation. It found that 45 per cent of those on an average income would run out of money completely within six months of the main earner losing their job.

In fact, it’s been a bit of a week for the middle-aged. The Financial Conduct Authority conducted their own survey into pension provision among Generation X; the words “retirement nightmare” were banded about with only a third of those asked having appropriate arrangements in place to provide for them post-65.

Add to that the sad story about the British man who plunged to his death from an ancient temple in India while on a “middle-aged gap year”, and the fact that the number of middle-aged men injuring themselves while having sex – mainly in the shower, apparently – has quadrupled in the past five years, and perhaps middle age isn’t the land of milk and honey that many people believe it is.

But is a bad middle age better than no middle age? Because despite the fact that no-one has yet been able to stop the advance of time, it might be that the millennials have a very good reason for their beef with the middle-aged. It’s not just because they have some primeval fear of growing old and that we, the middle-aged are a shambling, grouchy reminder of their own mortality.

It’s because millennials might never have the chance to even pull on a cardigan and book an escorted coach tour of the Italian lakes at all.

It’s almost impossible for millennials to get on the housing ladder, for starters. Mortgages are almost a fantasy, and rents are going the same way. An education is still a possibility, so long as you’re happy to leave university with £50,000 of debt. And while unemployment might be at four-decade low, wages are back to 2006 levels thanks to endless pay freezes and belt-tightening, and unpaid internships seem to be the only prospects in town half of the time.

Brexit is now being forecast to usher in an economic crisis, even by those who campaigned for us to leave the European Union in the first place.

And the bad news? Things might not get any better, especially for millennials. And there’s actual thinking behind this. It’s called the Strauss-Howe Generational Theory, and it posits a constantly-turning cycle of phases in modern life.

The theory says that there are four “generational archetypes”: Heroes, Artists, Prophets and Nomads. Which category we fall into depends on when we were born, and for each generation, the archetype dominates society during middle age – for these purposes, aged 40-60.

Heroes are so called because they hit their adult life during a time of great crisis and upheaval. The artists are the children of the Heroes, and they rebuild the world after the period of crisis. Prophets are the next generation, and they become moralistic and inevitably begin patterns of behaviour which will lay the groundwork for the next crisis in the cycle. Finally, there are the Nomads, who are born after the crisis and grow up distant from it, and have idealistic plans for their own children… the Heroes.

All of which sounds like a lot of New-Age gobbledegook. But the archetypes in Strauss-Howe are allied to a further series of cycles, which they call “turnings”. These are: High, Awakening, Unravelling and Crisis. The High Turning is a period of stability, but with the focus on institutions rather than individuality. This is when the Heroes enter middle age.

The Awakening is basically when things turn around and the focus is on people and individuals rather than corporate bodies. The Unravelling is what happens after the optimism of the Awakening begins to sour. And the Crisis can be war, economic collapse, erosion of civil liberties, as the establishment begins to re-assert itself in readiness for a new High Turning.

It’s when you map those Archetypes and Turnings on to recent history that things get interesting.

Archetypes first: those born between 1925-1942, the so-called Silent Generation, are said to be the Artist archetype. The Prophets are the Baby Boomers, born between 1945 and the early 1960s. Generation X are the Nomads, which means the millennials are the Heroes.

On to the Turnings, the last High is considered to be the post-World War II years. The Awakening was 1961-1981 – the Swinging Sixties, the Sexual Revolution, the focus on free-thinking and social revolution. The Unravelling was the greed-obsessed 1980s and the War on Terror early 2000s. Which means, as of the financial crash of 2008, we’re right in the middle of the latest Crisis.

But you knew that anyway. What that means is that we’re in the age of Heroes – of the millennials. The millennials are idealistic, want a better society and desire more stability. That’s the good news. The bad news is, they’re going to have to fight for it, and aren’t going to see it – if the Strauss-Howe Theory holds – until they themselves are middle-aged, or even older. And it’ll be the next generation, the Artists, the children of Generation X, who will benefit.

So if you’re grumpy and middle-aged, cut the millennials some slack. They’re the ones who are going to create a better world for our kids, and they’re not going to have an easy time doing it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments