‘If the smell can get out, so can the virus’: Stench of foot-and-mouth farms was only the beginning

When Paul Vallely visited affected farms in March 2001, the piling up of dead animals, left unburied for as long as a week, was just the latest problem for farmers left struggling after the outbreak

The sound of hollow laughter could be heard echoing round the nation’s farmyards yesterday after the minister of agriculture, Nick Brown, appeared on the television and claimed he was “absolutely certain” the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease was now under control. Not that they were laughing at Blackrigg Farm near Longtown in Cumbria. There the air reeked from the carcasses of animals that had been slaughtered three days earlier but had yet to be disposed of by the Ministry of Agriculture (Maff) officials.

“The place is stinking,” said Robert Storey, from one of the families who farm on the small lowland holding. “There’s effluent and blood running out of the buildings and into the yard. It is not a nice place to live.”

The piling up of dead animals is the latest problem for farmers afflicted by the outbreak. In parts of Devon yesterday there were carcasses that had been left unburied for as long as a week, according to John Hodge, a hill farmer and chairman of Dartmoor Commoners.

“There are mounds of carcasses crawling with rats eating the tongues out of the cattle,” he said. “There was one report of a huge pack of rats swarming across the road from one infected farm to another where the disease hadn’t been reported. Mr Brown may think the situation is under control elsewhere, but it certainly isn’t here.”

Promises of rat-catchers at the sites of the carcasses had not been kept, he added.

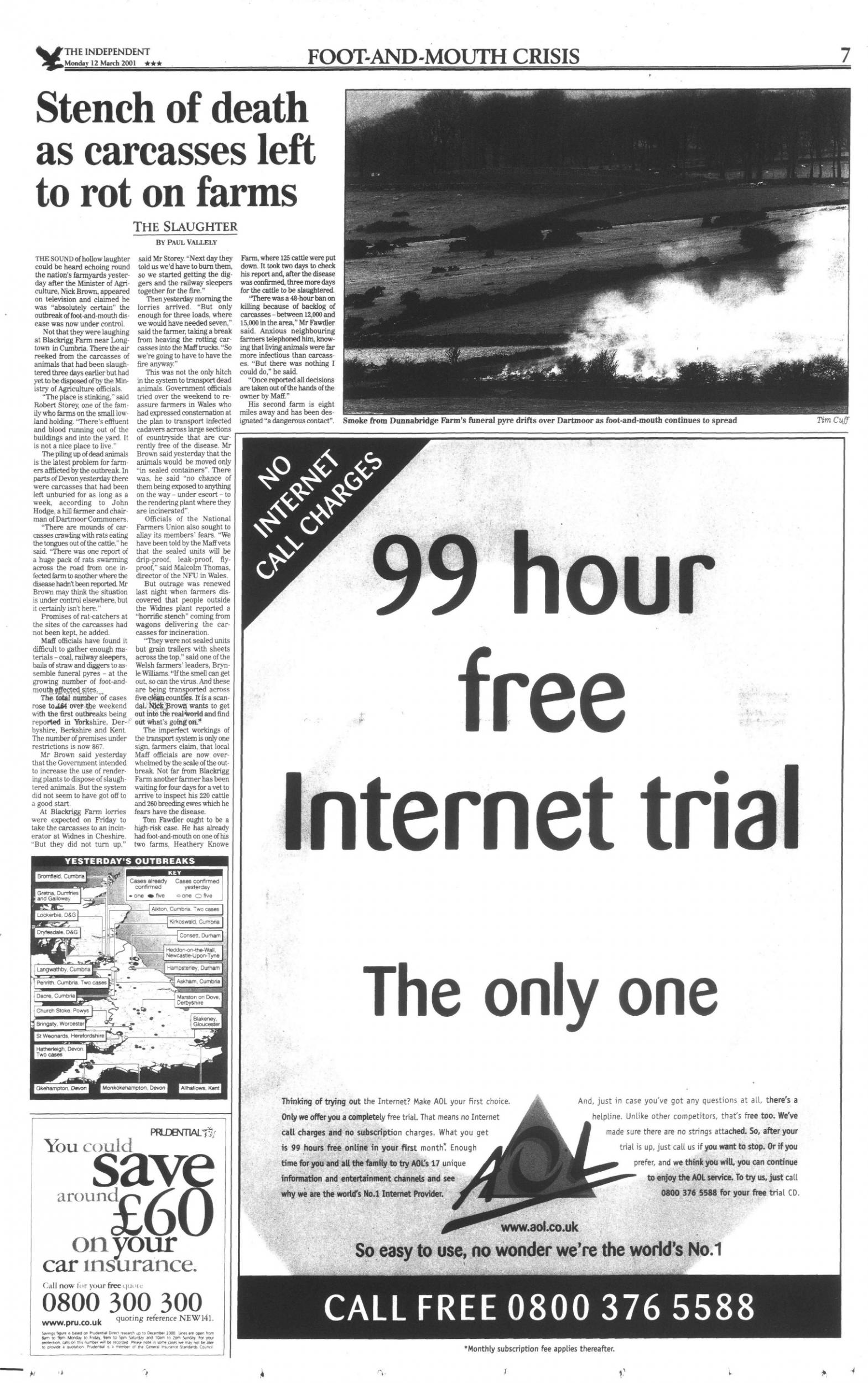

Maff officials have found it difficult to gather enough materials – coal, railway sleepers, bails of straw and diggers to assemble funeral pyres – at the growing number of foot-and-mouth affected sites.

The government claimed it had everything under control – but did it? Read part four

The total number of cases rose to 164 over the weekend with the first outbreaks being reported in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Berkshire and Kent. The number of premises under restrictions is now 867.

Mr Brown said yesterday that the government intended to increase the use of rendering plants to dispose of slaughtered animals. But the system did not seem to have got off to a good start.

At Blackrigg Farm lorries were expected on Friday to take the carcasses to an incinerator at Widnes in Cheshire. “But they did not turn up,” said Mr Storey. “Next day they told us we’d have to burn them, so we started getting the diggers and the railway sleepers together for the fire.”

Then yesterday morning the lorries arrived. “But only enough for three loads, where we would have needed seven,” said the farmer, taking a break from heaving the rotting carcasses into the Maff trucks. “So we’re going to have to have the fire anyway.”

This was not the only hitch in the system to transport dead animals. Government officials tried over the weekend to reassure farmers in Wales who had expressed consternation at the plan to transport infected cadavers across large sections of countryside that are currently free of the disease. Mr Brown said yesterday that the animals would be moved only “in sealed containers”. There was, he said, “no chance of them being exposed to anything on the way – under escort – to the rendering plant where they are incinerated”.

Officials of the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) also sought to allay its members’ fears. “We have been told by the Maff vets that the sealed units will be drip-proof, leak-proof, fly-proof,” said Malcolm Thomas, director of the NFU in Wales.

But outrage was renewed last night when farmers discovered that people outside the Widnes plant reported a “horrific stench” coming from wagons delivering the carcasses for incineration.

If the smell can get out, so can the virus. And these are being transported across five clean counties. It is a scandal

“They were not sealed units but grain trailers with sheets across the top,” said one of the Welsh farmers’ leaders, Brynle Williams. “If the smell can get out, so can the virus. And these are being transported across five clean counties. It is a scandal. Nick Brown wants to get out into the real world and find out what’s going on.”

The imperfect workings of the transport system is only one sign, farmers claim, that local Maff officials are now overwhelmed by the scale of the outbreak. Not far from Blackrigg Farm another farmer has been waiting for four days for a vet to arrive to inspect his 220 cattle and 260 breeding ewes which he fears have the disease.

Tom Fawdler ought to be a high-risk case. He has already had foot-and-mouth on one of his two farms, Heathery Knowe Farm, where 125 cattle were put down. It took two days to check his report and, after the disease was confirmed, three more days for the cattle to be slaughtered.

“There was a 48-hour ban on killing because of backlog of carcasses – between 12,000 and 15,000 in the area,” Mr Fawdler said. Neighbouring farmers telephoned him anxiously, knowing that living animals were far more infectious than carcasses. “But there was nothing I could do,” he said.

“Once reported all decisions are taken out of the hands of the owner by Maff.

His second farm is eight miles away and has been designated “a dangerous contact”.

This article first appeared in The Independent on 12 March 2001

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks