The Conjuror on the River Kwai: One man's battle to survive the horror of war and save comrades using magic tricks

'I was blown up, I was shot, I survived a massacre, I was buried alive twice and I was up in front of a firing squad twice. Apart from that it was all right'

Fergus Anckorn was a member 118th Field Regiment Royal Artillery and member of the Magic Circle, who aged 23 was captured by the Japanese in Singapore without firing a shot. What followed was a story of almost unimaginable suffering, stoicism, mental fortitude and endurance; he survived the ruthless regime that the Japanese Imperial Army imposed upon Allied PoWs working on the Burma-Siam Railway, the so-called Death Railway, while also surviving a number of brushes with death.

He earned the moniker of “the conjuror of the River Kwai” as he saved fellow prisoners’ lives by distracting and entertaining the guards so they allowed him to have extra food rations. His story inspired Lance Corporal Richard Jones, serving in the Household Cavalry, to retell his story in a card trick to win Britain’s Got Talent, in 2016, with Anckorn appearing alongside him in the final.

Asked about his wartime experiences, Anckorn replied calmly, “I was blown up, I was shot, I survived a massacre, I was buried alive twice and I was up in front of a firing squad twice. Apart from that it was all right!”

Born in Dunton Green, near Sevenoaks, Kent, in 1918, Fergus Gordon Anckorn was one of four children. His interest in magic was sparked after receiving a magic set for his fourth birthday; thereafter, he started to perform tricks at parties and, aged 18, became the youngest member of the Magic Circle.

Educated at the Judd School, Tonbridge, he left at 16, and encouraged by his father, a journalist, took a two-year journalism course at Regent St Polytechnic, though never pursued it as a career. After a couple of menial jobs, he began working as a clerk at the Marley Tile Co in Sevenoaks. With the outbreak of war in 1939, most of the clerical staff of enlistment age were summoned and sacked.

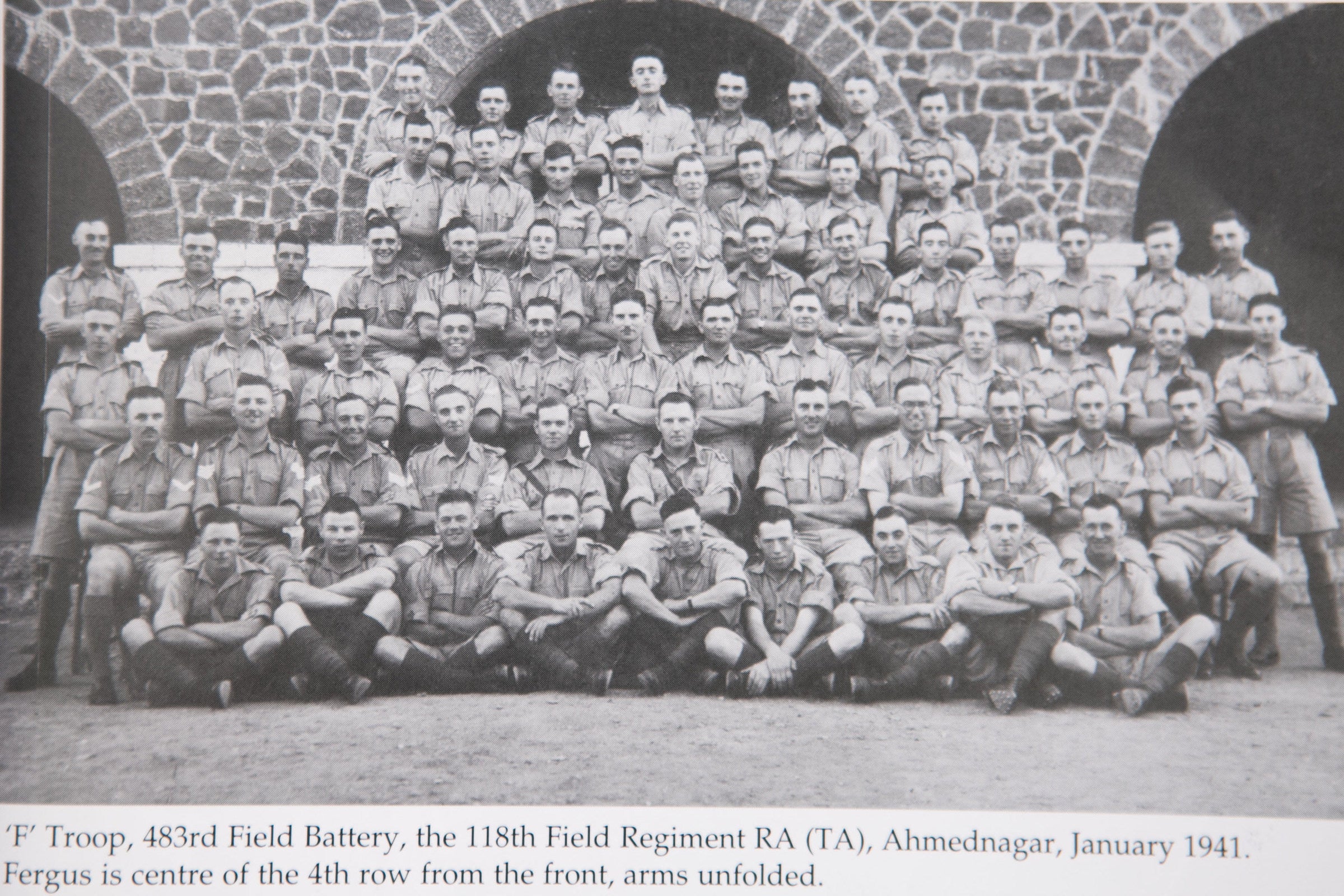

Anckorn was one of the first to be called up. After training at the Royal Artillery Barracks, Woolwich, south London, where he met the artist Ronald Searle, he joined the 118th Field Regiment Royal Artillery as a gunner.

Over the next two years, he continued to entertain his fellow comrades with his magic, while also being sent on different assignments around the country, one of which included guarding the beaches at Eastbourne during the Dunkirk evacuation. During this period, he also spent time in Joyce Green hospital, Dartford, following a severe skin condition; here he met Lucille Hose, a nurse, who soon became his fiancée.

In early 1942 the regiment was shipped off to India but were redirected to Singapore to re-enforce the garrison there. No sooner had the 118th disembarked in Singapore than they were dive bombed by Japanese Aichi bombers and Zero fighter-bombers. Anckorn sought refuge by diving into the dock but upon emerging discovered that five of his comrades had been killed.

Less than a week later, while driving a truck of munitions, he ran into an air raid and his truck was blown up by a bomb blast. He sustained a severe blow to the head, burns and shrapnel wounds, but worst of all, his right hand was almost severed, held on by a piece of skin. Barely alive, he was taken to Alexandra Military Hospital. Thanks to an orderly who recognised him in time, the surgeon did not amputate the hand as he was intending to.

Singapore was now under siege from Japanese forces and on 14 February the hospital found itself cut off from the retreating British troops and the advancing Japanese. Soon the hospital was swarming with Japanese combat troops, who perpetrated one of the worst atrocities of the war.

Moving from ward to ward and bed to bed, the Imperial Army bayoneted patients to death or shot them, as well as nurses, doctors and auxiliaries. A surgeon, busy operating in the theatre, together with his anaesthetised patient was similarly dispatched. It was an indiscriminate blood bath.

Seeing the flashing bayonet blades heading his way, Anckorn, who was semiconscious and blood-stained all over, pulled a pillow over his face and awaited his fate, muttering “poor Mum” to himself. However, thinking he was already dead due to the blooded sheets, the Japanese went straight past him and he heard the cries of the man beside him. When he came round, “everyone was dead except for me.” Of the 72 on his ward, only four survived.

Some 200 patients and personnel were rounded up and, with their hands tied behind their backs with a slipknot of barbed wire, shoved into small rooms to asphyxiate; others were simply shot for sport and the rest sent to camps. In all almost 200, mostly British, were murdered.

Singapore, nicknamed the “Gibraltar of the East”, fell the following day with the capture of approximately 80,000 British, Indian and Australian troops, adding to 50,000 captured weeks before; Winston Churchill called it the “largest capitulation” in British military history.

Upon discovering he was alive, Anckorn was taken captive, and his arm was operated on in a rudimentary fashion. Found to be gangrenous, the wound was "disinfected" with maggots, which devoured his rotting flesh, and then had to be removed from under the skin without anaesthetic. The treatment worked and his hand was saved though it was almost crippled.

Anckorn, now a PoW with others from the 118th, were forced marched to Changi Prison and observed Japanese punishment as the road was lined with the heads of decapitated Chinese on spikes. He saw further brutality when an old Chinese woman was caught throwing a bread roll to the PoWs. Witnessed by the Japanese, she was tied by the ankles, hung upside from a tree over a fire and roasted alive.

Anckorn recalled, “I never understood their mentality … Life was nothing to them and they had no fear of death. We were merely tools to build the railways … if we broke it didn’t matter.”

The prisoners taken captive during Japan’s advance towards the Malayan peninsula were treated abominably and subjected to brutal treatment and torture in sprawling prison camps across South-east Asia. Anckorn was sent north with tens of thousands of others to work on the notorious Burma Railway, immortalised in David Lean’s 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Though still weak, malnourished and enduring savage beatings like so many PoWs, Anckorn started working on the Wampo viaduct, which consisted of wooden trestles alongside the river, nestling against the cliff side, all carved out by hand.

Working up to 16 hours a day in a loincloth and barefooted, the men survived on a few handfuls of rice a day. Food was scarce, forcing prisoners to eat anything they could find – from maggots to scorpions, from snakes to mice, cats and dogs – anything that moved, though many thousands starved to death.

One afternoon, Anckorn was ordered to make the 100-foot climb up the bamboo viaduct to apply boiling creosote to reinforce the wooden struts. However, he had an attack of vertigo and froze with fear. An enraged guard climbed up after him and threw the five-gallon creosote container over Anckorn’s head, causing blistering and swelling to his skin.

“Fortunately, I had a banana leaf hat on my head,” he recalled, “which protected my face, but I was aware of my shoulders and chest suddenly roasting.”

He said his goodbyes and was dispatched to the hospital at Chungkai camp in Thailand, seen by many as a cemetery, but “three weeks later my comrades were all dead. If I hadn’t been burnt I would have been dead too.”

While there, he regained some of his strength and started to do some simple magic tricks to maintain morale. Word got back to the sadistic camp commandant, Osato Yoshio, who adored magic. As well as killing his pet dog for fun with a revolver, Osato had once forced six prisoners to line up in front of six guards outside his hut, then ordered his men to beat them until nearly dead.

Osato summoned Anckorn and gave him a small coin. He successfully made it disappear, and miraculously discovered it in an opened tin of fish sitting on Osato’s table. A delighted Osato let him leave, along with the precious tin of food because it was deemed contaminated, as PoWs were seen as “verminous”.

Anckorn suddenly realised that he could supplement the meagre food rations by doing magic using the food as props.

One day Osato ordered Anckorn to perform for some high ranking visitors and wrote him a note so that he could obtain an egg from the Japanese cookhouse. He used the note, which did not specify that he needed a single egg, to obtain 50, which he immediately distributed to his comrades. He saved one egg for his trick and the performance went well; however, the next day he was summoned by the commandant to explain the whereabouts of the other 49 eggs. Aware he could be beheaded, “As quick as a flash – I don’t know where I got the inspiration from – I said, ‘Your show was so important, I was rehearsing all day’.”

“Osato nodded and let me go,” Anckorn recalled. “He probably knew that I was lying but it was enough to save his face … I couldn’t perform that trick again for 40 years.”

He was transferred to other camps and continued to perform magic but, one day in mid-August 1945, as the war drew to its conclusion, Anckorn thought his time was up. He and four others were bundled into a truck, unusual in itself as they always walked barefoot everywhere, and driven into the jungle. They were put against some trees, without blindfolds, and a machine gun was mounted onto a tripod. After 10 minutes of waiting for the inevitable “for some reason they decided against it”. Upon returning to the camp, they discovered that the war had been over for three days.

After liberation, Anckorn weighed just five stone and of his regiment of 980 taken prisoner, 250 survived. Of those taken prisoner in Singapore, two-thirds died there.

He was not allowed to return to Britain yet as he “looked too horrible” and needed fattening up. After three months of eating, he returned home, although he still weighed only six stone.

While in LondonAnckorn was tapped on the shoulder by someone he thought was a stranger, but was in fact Sir Julian Taylor, the surgeon who saved his hand at Alexandra Hospital. He later operated on his hand and wrist so that he could have movement again, allowing him to continue his conjuring and eventually become the oldest member of the Magic Circle.

He found it hard to adjust to civilian life and led a quiet life, combining his magic with his duties as a special police officer, as well as a shorthand teacher at West Kent College in Tonbridge.

Despite the horrors he suffered and witnessed, Anckorn was not a man for self-pity and even considered himself lucky. “We all came through it – it’s amazing what the human frame can put up with and get away with.”

He bore no grudges against his captors and learnt to read and write Japanese from a Japanese lady, who eventually paved the way for him to go over to Japan to give lectures about what happened.

In 2011, his memoir was published, Captivity, Slavery and Survival as a Far East POW: The Conjurer on the Kwai.

He married his sweetheart Lucille on 26 January 1946 and the couple had two children. She predeceased her husband. Anckorn is survived by his children.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks