The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How the public lost faith in traditional politics – and turned to populism

In a new book, John Redwood says the big political parties have been all but destroyed in elections by the rise in populist movements around the world. So why didn’t experts foresee it? And is it such a bad thing?

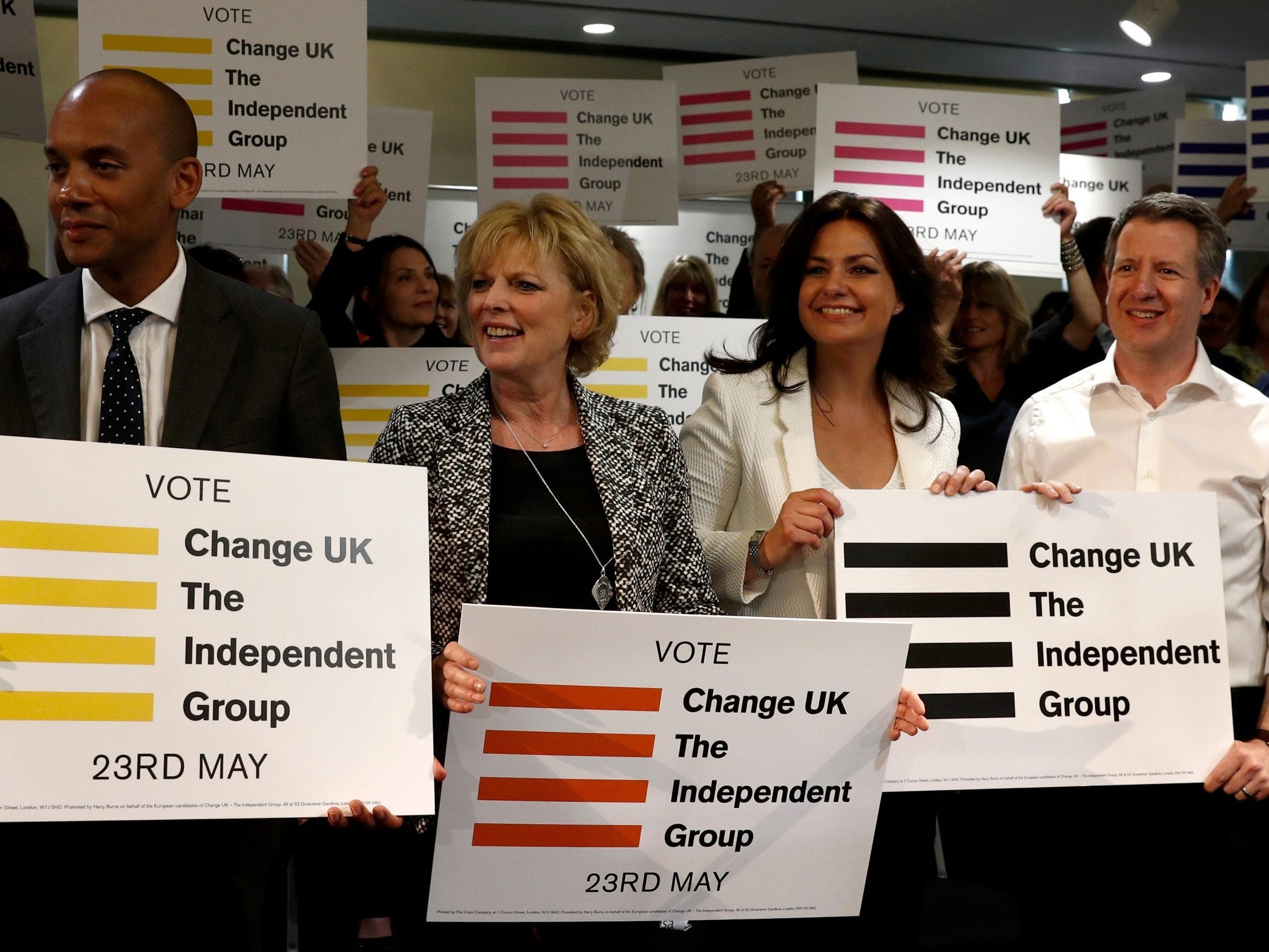

I assumed the UK would be out of the EU on 29 March 2019, as often promised by the prime minister – with or without a deal. Instead I find my book, on the growing gap between traditional parties and the voters, and growing distrust of experts and governing institutions, is eerily topical for the UK as well as the rest of the EU, as background to the recent European elections. The UK became caught in a time warp, fighting European elections three years after it decided to come out. Two new challenger parties, the Brexit party and Change UK, the Remain party, emerged to turn the elections in the UK into a kind of rerun of the referendum vote.

Change was soon supplanted in its aim by the Liberal Democrats, an old protest party reborn as Remain campaigners. The Establishment, Lib Dems and Change UK battled to keep the UK in and to prevent any alteration in our relationship with Brussels, whilst the Brexit party campaigned to implement the referendum decision. Change UK found it difficult to explain why they call themselves Change, when they are a force against change when it comes to accepting all the rules, laws and powers of the EU, the current number one topic of debate. They also suffered from the fact that the MPs that formed them had campaigned in the 2017 election on either the Labour or Conservative Manifesto which promised Brexit.

The two traditional main parties, Labour and the Conservatives, claim to still want the UK to leave the EU. Meanwhile Labour has many MPs and members who want to reverse Brexit and propose a second referendum to do so, undermining their credentials with Leave voters. The Conservatives under Mrs May promised to leave by 29 March this year with or without a deal. At the last minute the prime minister decided to seek a delay in our leaving instead.

This provided plenty of space for the new Brexit party to woo former Conservative voters with the offer of an early Brexit, without signing the Withdrawal Treaty. The two main parties plunged in the polls, from a combined 82 per cent in 2017 to just 23 per cent in the Euro elections. These embarrassingly low results were new lows for both parties. Mrs May’s Withdrawal Agreement was on the ballot paper as the only Conservative policy and scored just 9 per cent, with remain voters saying they preferred to stay in and Leave voters saying it was not leaving.

The irony of all this is that the UK detached itself from the continental trend of the demise of the two traditional centre left/centre right parties by adopting Brexit two years ago, only to now be locked into a rapid and unexpected version of the continental collapses, thanks to the failure of Parliament to deliver the results of the referendum. The Conservatives can only rescue themselves by delivering an early and clean Brexit to win back Brexit party voters. Labour can only hope to recover if an early Brexit gets through and allows them to concentrate on something else. If they simply shift their party more clearly to Remain, they compete in a very crowded market and lose most of their remaining Leave voters.

On the continent of Europe the disillusion with traditional parties stems from a variety of causes. Many voters are tired of austerity which they attribute to the Euro and the budget controls emanating from Brussels. In France, Emmanuel Macron’s keen green policies put up fuel tax and imposed new speed limits. The Gilets Jaunes movement emerged to demand lower fuel taxes, and went about their business closing down many speed cameras as a pro motorist protest. In Greece, Syriza has long since swept aside the old Greek version of the Labour party in rebellion against spending cuts and tax rises.

In Italy, the unlikely pairing of Lega and Cinque Stelle command over half the vote and are together in coalition government. The old Christian Democrat and Social Democrat parties scramble around to keep a third of the vote between them. Even in Germany, the economic winner from the Euro, the two old political firms are under the electoral cosh, on a combined 40 per cent of the vote. They are in grand coalition together as they try to keep out the challenger parties and the Eurosceptics.

The elites of the main advanced countries have all struggled for credibility after a number of hammer blows to their authority. Electorates tired of the Middle Eastern wars, where western forces behaved well militarily, but the politicians and diplomats were unable to create the stable democracies they talked about.

The banking crash and great recession at the end of the last decade left Treasuries and Central banks wallowing to explain why they had not been able to forecast these bad events or to do something to stop or cushion them. The large scale migrations worried many voters, whilst static or falling real wages made people look for change. The elite’s agenda based around climate change, the threat of terrorism and the search for political correctness annoyed many voters.

In areas from migration to climate change, from fake news to austerity, from European integration to devolution, people are shouting back to the governing institutions: “We don’t believe you”. There are disagreements between governed and governments not just about remedies, or about who is to blame for a problem, but about what the true problems are. The elite is busy tackling things many voters do not worry about, or want them to leave alone. They are failing to raise real incomes, control migration and give people a sense of empowerment over their government in the way they seek.

As a result, the grand old parties are in decline and new challengers are springing up, attracting substantial support. The UK looked as if the main parties had found an answer called Brexit. It now appears with that on hold that the UK is rejoining the European pack.

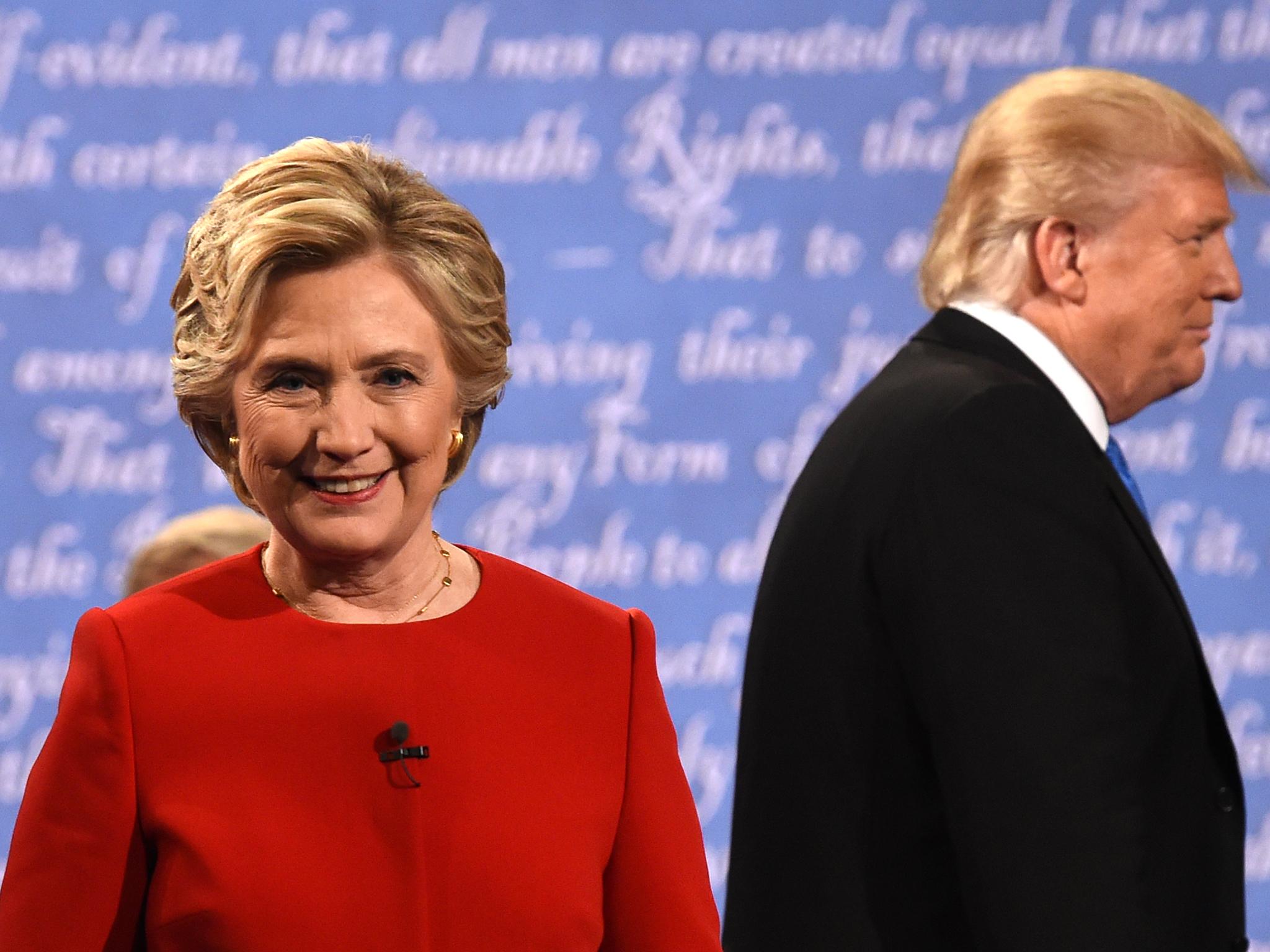

In the USA, similar pressures arose but were contained within the traditional parties. Donald Trump brought an insurgency of challenger mentality to the job of Republican candidate, much to the shock of the Republican establishment. Bernie Sanders almost lifted the Democrat candidature for President off Hillary Clinton by moving the party to the left.

The current early days of the race for the next Democrat candidate may see similar tensions play out, as the party tries to decide how radical to be and how to get back in touch with former Democrats, as well as people who have not been voting because they spurn the elites and their agenda.

Chapter 1

Populist movements around the world are on the rise. Many more people are saying to the experts and the elites who would continue to govern them, “We don’t believe you”. The Emperors have no clothes. They have cried wolf too often on worries they have for the public to trust them.

The biggest western failure was the complacency about banks and banking throughout the first seven years of this century. It was followed by a spectacular crash and great recession, engineered by the very governments and Central banks who had presided over the credit bubble

Worse still, their fabled expertise has so often led their countries and the world system into trouble. If you look for a single issue which did more than others to fuel the distrust and to fan the flames of radical politics, it is the failure of the economic elite to foresee crashes and crises.

Over the last ten years, real incomes have fallen in several advanced countries and risen slowly elsewhere. The public feels let down by the experts and expects them to help deliver faster and better progress to higher living standards.

The biggest western failure was the complacency about banks and banking throughout the first seven years of this century. It was followed by a spectacular crash and great recession, engineered by the very governments and Central banks who had presided over the credit bubble.

They failed to alert people to its dangers and then brought the banks crashing down as if it had nothing to do with them. As the Queen asked in the UK, why didn’t the experts see it coming?

Of course, in practice some experts did, but we were marginalised, excluded from positions of power by the great consensus. The false expertise of the establishment blandly told us this time it would be different. The experts in authority told us that banks were now large and global. They had better ways of managing risk. It was therefore just fine for these global banks to have so much less cash and capital relative to the business they wrote than had been fashionable in the previous century.

The advent of more derivatives, options, securitised loans and big capital markets meant we need not worry. The leading banks would use these devices to offset risk. They would not be stretched if large numbers of depositors wanted their money back at the same time. There was, according to the elite, no reason for that to happen.

The experts were wrong.

We now know that they were wrong. The heavily leveraged positions in options and derivatives meant some investment funds and institutions were dangerously over committed and vulnerable to any downturn. Instead of using new vehicles to offset they risk, they often used them to raise it to increase profits in good times.

Worse still, having created a system that built up huge debt mountains backed by modest sums of cash and capital, the authorities then proceeded to blame the banks and to bring them down for having inadequate balance sheets.

The regulators acted as if they had been unaware of what was happening. They undermined a system which could have been deflated more gently with less public worry from highlighting its failings. The public denunciation of the banks by regulators encouraged depositors to queue to get their money back in a hurry.

Many people now recognise the big error made in allowing far too many loans to be made without the banks making proper provision for losses. Fewer commentators to this day see in some ways the larger error. Having allowed easier terms, the central banks and governments suddenly changed their mind. They rushed into expecting banks to hold large additional sums of capital which they found difficult to raise against the background of alarms set off by their regulators. Pointing out the frailties created made the crisis more immediate and more dramatic.

The public was fairly willing to blame the commercial bank executives, and to go along with the establishment view that this was primarily a private sector banking error.

Pursuing cases against banks and bankers for mis-selling, for running too much risk, for manipulating markets and the rest was a popular sport. The public egged on the authorities, and if anything felt too few bankers were fined or imprisoned for all the excesses that occurred.

There was no similar wish to pillory the central bankers who had allowed these extreme behaviours and had acted as apologists. They had shared the view that these extra risks were fine owing to the global nature of the big banks and their superior risk management with a wide range of so called risk reducing instruments to hand.

The establishment decided if it cut loose the commercial bankers and blamed them, it would survive itself. Reading many of the commentators and newspapers of the time, it seemed they got away with it.

In practice the establishment was badly damaged and seen to be generally responsible for the disaster. Voters took delight in getting rid of incumbent governments who had presided over the crash.

In the USA, the Presidency switched from Republican to Democrat during the worst period of the crisis. In the UK, the long-lived Labour government was swept from power at the first general election to follow the recession.

Why should we believe their next set of forecasts when they simply were unable to forecast the great recession even a few months before it hit?

On the continent where the crisis took longer to come through but was worse and more prolonged thanks to the Euro, government after government fell, as we will see later in this story.

Something else gave as well. The reputation of experts and large economic institutions like the IMF, World Bank, national central banks and treasuries also suffered long-term damage. None had forecast the collapse. None had taken early action to cushion or avoid the collapse.

Why should we believe their next set of forecasts when they simply were unable to forecast the great recession even a few months before it hit?

Their reputations were to suffer more and for longer because of the way they handled the aftermath of the crisis. Instead of doing everything to cushion the blow and then to speed the recovery, they opted instead for a series of policies that were soon called austerity.

In the UK, the authorities switched from defending the build-up of credit and derivatives, to stating that it had gone too far and the commercial banks were to blame. They told them to rein in their balance sheets, cut down their loan books and raise more cash and capital in a hurry.

The Governor of the Bank of England told them it was not the central bank’s task to bail them out, and they had to pay the price for their own moral hazard.

The first major casualty was Northern Rock, a mortgage bank that had expanded rapidly in the previous few years. The general words of the regulators led to a sharp loss of confidence in the bank with too many depositors wanting to withdraw their money.

The collapse led to a reconstruction, with the authorities changing their stance and putting money into markets to try to ease the squeeze. It was difficult to see what was gained by allowing the collapse of a bank that was in the early days illiquid rather than insolvent. Forcing early disposals of loans helped make it insolvent.

Triggering the recession which duly followed the banking crash then turned many of the good loans into bad loans for various banks intensifying the squeeze further.

The establishment did not learn from the bitter experience of Northern Rock. They did end up putting plenty of cash into the system to prevent the complete collapse of the bank, but only after the run on deposits and the forced recapitalisation

The Northern Rock business model entailed lending on mortgage for house purchase. The bank then sold on some of the loans to other market participants so the bank could carry on expanding the mortgage portfolio.

Securitising or selling on loans was a strong part of the model, taking risk off Northern Rock’s balance sheet and allowing it to expand mortgage business further.

Once this was questioned by the regulator it became more difficult for the Bank to sell the mortgages on for a profit, leaving it exposed to rumours and worries about its solvency.

The Bank of England as lender of last resort to the commercial banks could have made enough cash available to Northern Rock to carry on, but chose not to. Many commentators argued that securitising the loans was the cause of the problem. Securitising was part of the answer to the problem, as it generated cash for Northern Rock and transferred the risk to others.

What brought the bank down was the inability to borrow enough short term money at an affordable price in a market starved of cash and gripped by fear, partly driven by regulatory comment and actions. This led directly to a run on the bank by depositors who were the people who forced action to save the bank.

The unlearned lessons

The establishment did not learn from the bitter experience of Northern Rock. They did end up putting plenty of cash into the system to prevent the complete collapse of the bank, but only after the run on deposits and the forced recapitalisation.

Instead of learning that earlier support coupled with a planned programme to strengthen the balance sheet would have avoided a lot of pain and cost, they did exactly the same to the much bigger RBS, intensifying the crisis a year later when a run started to emerge on RBS deposits.

Taxpayers ended up having to underwrite and partially pay for a very expensive bail out of some of the leading commercial banks, which added to public anger about what had happened. When RBS was given state capital it had a balance sheet valued at £2.2trn. That was more than the GDP of the entire UK that year. It was almost too big for the UK state to accept as a risk. A loss of just 2 per cent of the assets meant the taxpayer would lose the equivalent of the entire defence budget for a year.

These figures did not stop an establishment in panic accepting such risks, despite other ways of handling the crisis being offered to them.

Worse was to follow. The mood of the authorities on both sides of the Atlantic shifted to a hostile approach to more borrowing. In the UK, the new coalition government formed from the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats after the 2010 election, determined that the public sector deficit had to come down.

At the same time the main commercial banks were told by the regulators to boost the ratio between capital and loans they had made, typically doubling it. In recessionary conditions banks were more inclined to do this by cutting back on loans than by raising more capital. So, austerity was born.

The gap between the rhetoric and the reality was damaging. Whilst some spending programmes were cut, the continued growth of overseas aid, EU contributions, NHS and benefit expenditure in total maintained modest growth in real spending

Car and mortgage loans were scarce, companies that wanted to borrow found it difficult, and the gap between public spending and tax revenue had to be altered dramatically from the unsustainable 10 per cent of GDP back down below the EU ceiling of 3 per cent.

The halving of RBS

RBS itself, the largest of the state supported banks, embarked on a massive balance sheet squeeze, halving the size of its assets and liabilities. It is amazing the UK economy did not do less well than it did, given the impact such a large reduction in credit would normally have on a captive economy.

The new Chancellor, George Osborne, was an enthusiast for the new puritanism. He told us that the UK government deficit had to be eliminated over the lifetime of a Parliament, and said he would do this primarily by reining in public spending, with just 20 per cent of the work done by the tax rises he proposed. This seemed an unlikely approach at the time given the pressures on spending and the spending proclivities of most politicians.

So, began a long argument I had with the Treasury over what the true figures were.

Whilst the Chancellor and the Treasury documents told us the bulk of the adjustment came from spending cuts, the official figures published in the Budget books showed a totally different picture. They showed that the plan was for a very small real increase in total public spending over the forecast period, with cash spending going up all the time to take care of inflation.

The deficit came down thanks to a massive increase in tax revenues. Tax revenues did expand thanks to modest economic growth and to the increase in the VAT rate, but not sufficiently to achieve the stated objective of eliminating the deficit altogether.

All of this gave austerity a bad name. The opposition both criticised it as a bad policy for those who suffered from the cuts, and criticised the government for failing to get additional borrowing down as planned. The Chancellor was especially keen to cut benefit spending

The gap between the rhetoric and the reality was damaging. Whilst some spending programmes were cut, the continued growth of overseas aid, EU contributions, NHS and benefit expenditure in total maintained modest growth in real spending. People however believed the words of the government, as it married with their personal observations of the programmes which were cut.

As always, the media and the opposition understandably concentrated on where the cuts were sharpest, so hardly anyone was pointing out that total spending was still rising.

Meanwhile the substantial increase in the tax burden placed an obstacle to growth. Enterprise was held back by high rates of income tax, stamp duty, capital gains and other taxes on enterprise. Some tax rates were clearly counterproductive leading to less being raised than if they had been lower.

After a long debate, the Chancellor did cut the top rate of income tax from the penal 50 per cent introduced as a poison pill at the very end of Labour’s period in office, and as expected revenue increased substantially.

All of this gave austerity a bad name. The opposition both criticised it as a bad policy for those who suffered from the cuts, and criticised the government for failing to get additional borrowing down as planned. The Chancellor was especially keen to cut benefit spending.

It is true that you can cut benefit spending by promoting growth, more jobs and higher pay. If benefit spending falls off because fewer people need the benefits – that is a good outcome. He also, however, decided to cut benefits for some who did need them.

Caps were popular

Putting an overall cap on how much total benefit a person or family could receive turned out to be a popular policy. Many felt it was wrong that someone not at work could pick up more net pay in benefits than someone on average earnings could earn after tax.

The decision to reduce payments for housing to those who lived in rented accommodation on benefits, who rented a home larger than they strictly needed, was more contentious. Dubbed the bedroom tax by Labour, it became an image of a cut too far for many. Someone in need of benefits did not want to feel they had to move to a smaller place at the same time as losing their job or hitting some other financial accident.

Austerity in the UK came to mean, for the rest of the community restrictions on pay awards, high levels of taxation, and a lack of progress in raising net incomes over a prolonged period.

It is true for much of the time after 2010 that real incomes were rising a little, but the drop in take home pay and disposable income during the crash years of 2008-9 had been large and it took time to recover.

Where many politicians saw austerity as primarily a public-sector phenomenon, with a knock-on effect to those dependent on benefits and public services, many others saw it as their own experience as they reflected on the decline in living standards brought on by the crash and slow progress in recovery. It took until 2015 for UK incomes on average to be above the real levels of 2007.

The European experiences

Austerity was altogether much fiercer in parts of the Eurozone. In the case of Greece, the austerity was both reflected in huge cuts in cash spending by government and by a big squeeze in real incomes for most others. The two interacted, as successive budgets cut cash pay for public sector workers by as much as one fifth, and cut pensions payable to the retired. In addition, tax increases were put through.

Greek living standards fell by a staggering one third and remain today well below 2007 levels. The programmes of cuts and tax rises were continuous through the last eight years as the masters of the Euro and the EU forced Greece into successive austerity budgets.

The opposition to this was active and continuous, mainly using parliamentary means. The public expressed their feelings in elections, striking out governing parties for their failure to find a way out of austerity

In the end, however, they reluctantly accepted the Euro scheme which depended on the austerity treatment. Italy had a less dramatic version of the same experiences. A country loaded with debt prior to the crash of 2008-9, the government had to accept regular budgets that pushed down on spending and increased taxes to try to bridge the gap between revenue and outgoings. The Italian economy grew very slowly, forcing more action on tax and spending to try to right the accounts.

The debates about austerity economics still rage.

The establishment say that austerity is a necessary discipline. They argue a country like a household or a business cannot borrow its way out of debt, and cannot borrow its way to faster growth. They argue that where a country such as Ireland took the harsh medicine, it was able subsequently to recover faster.

The problem with the Irish example is the way the Irish government kept corporate taxes far lower than most of the rest of the EU, which successfully attracted more business and capital. This met with disapproval by the EU, but not to the point where they prevented it happening. It was a model that the EU could just about tolerate for a small country, but would have been altogether more challenging if an Italy or Spain had tried it.

The critics of austerity make various arguments. They point out that success as in the cases of the UK and Ireland in getting the deficit down, whilst also growing, owes a lot to setting lower tax rates – not higher ones. The austerity plans of the EU usually require higher tax rates. They argue that borrowing more to invest and grow may succeed in cutting debt later, as deficits are very sensitive to rates of growth of the supporting economy.

The Italian and Greek deficits have proved intractable partly because their GDP has been static or falling, reducing the amount of tax revenue raised and increasing the strains on public spending, particularly for benefits. If growth had been faster, benefit spending would have been lower and tax revenue naturally more buoyant.

They will accept the need to right the mess created by a banking crash and recession, but will be more sceptical if the same establishment that landed them in the mess seeks to get them out of it

The Italian budget deficit argument in 2018 was about just this issue. The coalition government argued that spending more and taxing less would reduce the deficit faster in later years, whilst the EU concentrated on the immediate impact which was to make the deficit larger.

Rising tensions

All of these arguments increased the tension between those who govern and those who have to live with their taxes and spending plans. It sometimes appeared as if the governing class took some pleasure in announcing more austerity.

When attention then passed to examining their lifestyles, they did not always seem to apply the same prudence or puritanism to their own lives.

On both sides of the Atlantic there was more intense scrutiny of perks and expenses claimed by the elites of the public sector, and more questions asked about the extent of their travel, their overnight stays, their conference going and their bonuses. It made it worse if the recipient of generous total remuneration and expenses was lecturing everyone else on the need to keep pay and benefits down.

There are limits to how much austerity people living in a democracy will stand. They need to be persuaded that there is a good reason for it, that it will end, and that there will be a better future at some point.

People will accept much more privation in a war when they agree their country has to fight for its survival and for its principles, as with the allies in 1939-45 against their Axis opponents.

They will accept the need to right the mess created by a banking crash and recession, but will be more sceptical if the same establishment that landed them in the mess seeks to get them out of it.

When governments change

It is true there is usually government change following such a crisis, as there was on both sides of the Atlantic after the crash of 2008. This helps create a willingness to follow a new lead. The danger is, however, that the leaders of the central bank, the commercial banks, the treasury and the other principal public sector institutions do not change their approach and show sufficient humility for past errors, which makes the task of recovery more difficult.

The UK made more rapid progress in recovery and had a more honest dialogue about past errors because it did have a clear change of government.

In the Euro area, as we will see, national governments came and went, but the overall direction and policy of the EU and the ECB carried on regardless, to the concern of the troubled countries to the south and west of the zone. There it was only the decision of the central bank to ignore German advice and to print money that prevented a far worse crisis.

When something goes badly wrong, like the banking crash, having accountable government you can sack does help emotionally as people wrestle with the damage their governing institutions have done to them.

The outcome was not worse because the authorities flipped from being austere about banks’ capital and money, to being accommodating through inventing Quantitative Easing. They wished to teach the private sector and its bankers a lesson by curtailing extra credit and imposing many new restrictive rules, but they did realise that would prevent money growth and impede recovery.

So, the Fed, the Bank of England and eventually even the European Central Bank set about creating more money themselves directly.

Normally extra money results from commercial banks’ lending money to people. That money is deposited back in banks by the companies and individuals that are paid it by the borrowers, so the banks can then lend some of it on again, thus multiplying money in the system

Instead the three main central banks of the west created new money in an account as only they can, and then went out and spent it on buying up government debt. This served to raise the price of such bonds, lowering the interest rate the government had to pay for future borrowings. It also meant the former owners of the bonds had cash which they could reinvest in riskier assets or spend. In practice it meant the government spent the money created without having to pay for it.

Austerity has been the characteristic of the last decade. Electorates are sick and tired of it. They feel there should now be some bonus or reward for past belt tightening

This is not normally carried out, as in conditions where the commercial banks can create money and finance growth it would be very inflationary to simply print more money. Countries that have tried it have ended up with damagingly high rates of inflation.

Electorates sick of austerity

This time, with broken and cowed commercial banks, there was no unacceptable general inflation. There was however a substantial asset price inflation as highly priced bonds were swapped for highly priced shares or properties.

Austerity has been the characteristic of the last decade. Electorates are sick and tired of it. They feel there should now be some bonus or reward for past belt tightening. Individuals look around at various causes, worrying about migration and its impact on wages, at governments cutting when spending is needed, at tax rises when people want to keep more of their own money.

These ideas fuel the radical political movements of right and left that wish to end austerity and offer something better. They say to governments who wage more austerity on unwilling voters, “We don’t believe you”. People think their austerity policies are either needless or self-defeating.

The second half of this article is extracted from ‘We Don’t Believe you – Why Populists and the Establishment see the World Differently’, by John Redwood, published by Bite-Sized Books, available from Amazon and other sellers

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks