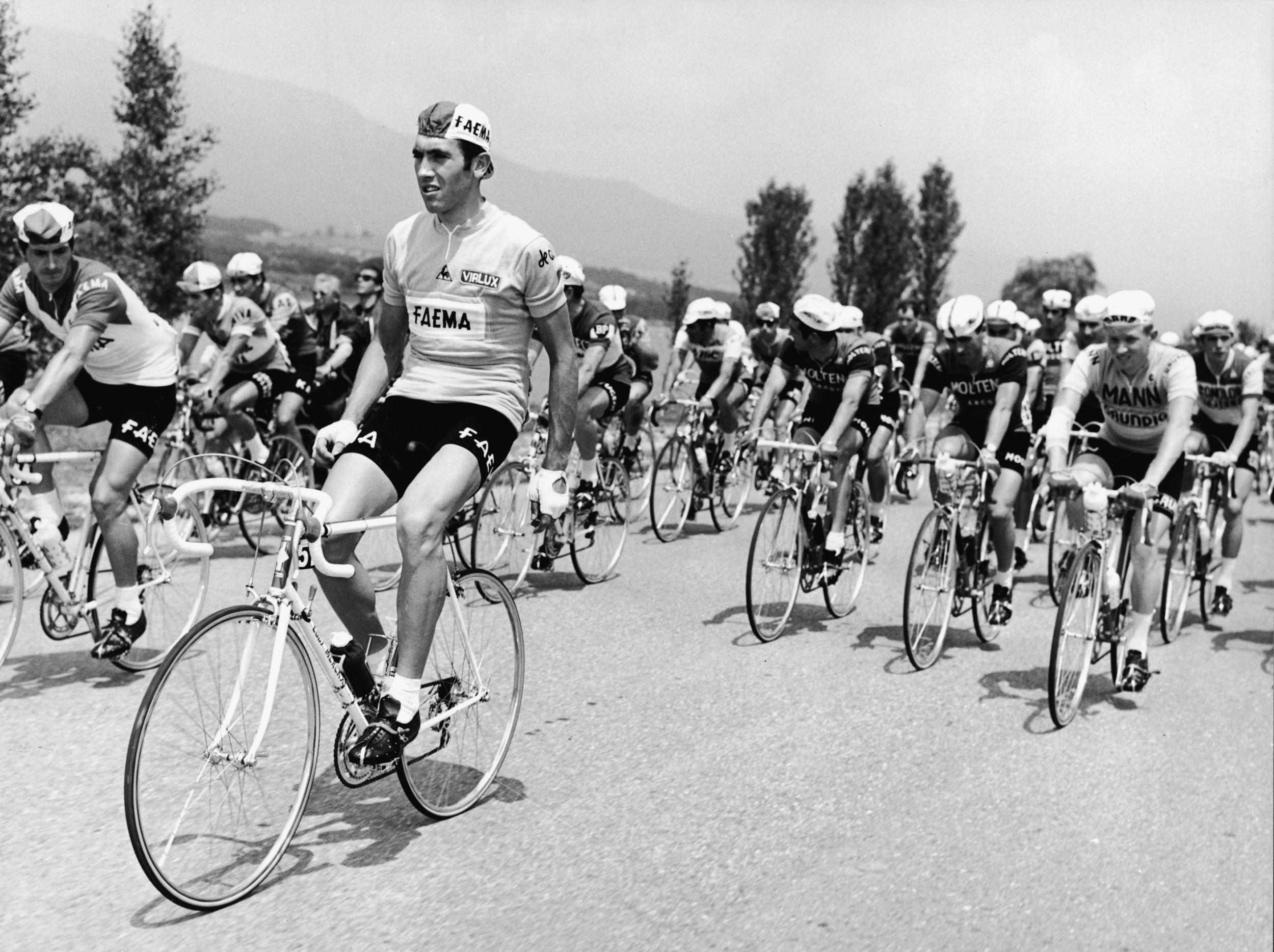

Eddy Merckx, the 1969 Tour de France and the day a Belgian legend was born

As ‘La Grande Boucle’ returns to Belgium on the 50th anniversary of Eddy Merckx’s first Tour triumph, Philip Malcolm remembers a glorious, transcendent moment of sport

Eddy Merckx’s victory in the 1969 Tour de France was one of those defining moments where an athlete exceeds what is thought possible in their sport. The 24-year-old Bruxellois rode with a combination of youthful abandon, the certainty of superiority and righteous fury. He was Usain Bolt running 9.69 in Beijing, Muhammad Ali toppling Sonny Liston, he was Maradona slaloming through the heart of the England defence in Mexico City.

To look back on it now, knowing what we know about Merckx’s career, it is easy to characterise it as just another step on the ladder towards the plinth he occupies as a statue: The Greatest Cyclist of All Time. If we look purely at the statistics, the Tour de France would simply be the next logical step in a career which, since turning professional in 1965, had garnered five monuments, a world championship and, answering those who had him down as a “merely” a one-day rider, the Giro d’Italia of 1968.

It is easy, with the filter of 50 years of familiarity with the rest of Merck’s palmarès, to become a little overfamiliar, a little jaded with the achievement. So indulge me as I reduce the 1969 Tour de France to a single sentence. Eddy Merckx, at the age of 24, won his first Tour by over 17 minutes.

It was a win that arrived in the shadow of a doping controversy, a hangover from the Giro in May, where Eddy was expelled while leading the race following a urine test after stage 16 into Savona of the 21-stage race. The TV footage of a tearful Merckx slumped on his hotel bed protesting a conspiracy by the Italians to ensure one of their own triumphed is an almost shocking contrast to the impassive, tyrannical figure he would cut during the Tour. Still protesting his innocence, Merckx had his month-long suspension overturned after two weeks and was given “the benefit of the doubt” by the authorities. A phrase which needled at the sensitive part of his personality all the way to Paris, wondering if every spectator whose eye he caught regarded him as a cheat. So intense was the media scrutiny that a study found that only the Kennedy assassination had previously generated as many words in the Belgian press.

The Belgian press was, you see, near obsessed with Merckx. He was their only global sporting star of the era and occupied a difficult position within the affections of the country’s cycling fans. It is almost impossible to overstate the place cycling occupies in Belgian, and especially Flemish, culture. It was, at the time, a defiantly working-class sport dominated by the Dutch-speaking part of the country which was both poor and marginalised, with French the language of government.

Winners of the Tour de France 2009-2018

2018 – Geraint Thomas, GB

2017 – Chris Froome, GB

2016 – Chris Froome, GB

2015 – Chris Froome, GB

2014 – Vincenzo Nibali, Italy

2013 – Chris Froome, GB

2012 – Bradley Wiggins, GB

2011 – Cadel Evans, Australia

2010 – Andy Schleck, Luxembourg

2009 – Alberto Contador, Spain

Merckx was not from the field or the factory, like most cyclists of the time. He had grown up in metropolitan Brussels, his parents were the petit bourgeoisie, owning a grocery shop. While Eddy expressed himself most easily in the Dutch language, a section of the Flemish fanbase were still suspicious of him having seen him leave Solo Superior (the most Flemish of teams) for Peugeot (the most French) in 1965 and then move to the Italian team Faema, which would be built around his talents. He had, in fact, caused a minor controversy by choosing to exchange his marriage vows in French. In truth, in the heartlands of Belgian cycling, Merckx was more respected than loved.

To cap it all, the first stage of the 1969 Tour de France would finish in Woluwe Saint Pierre, the Brussels suburb where his parents still kept their shop. It was where Merckx would take the first of the 96 days in yellow he would enjoy in his career, a win in the team time trial capitalising on Eddy’s second place in the previous day’s prologue. Stage three would see it loaned out to teammate Julien Stevens who won from a breakaway into Maastricht after the race crossed the Ardennes. From there on, it would spend only one day outside of the Faema team, on the shoulders of Desire Letort, before Merckx took control.

Stage six, with a summit finish on the Ballon d’Alsace, Merckx would serve notice on the Tour de France by arriving 55 seconds ahead of everybody and more than two minutes on all his serious rivals. In the modern age this would be a lead to be defended. Any serious team leader, with a Grand Tour already under their belt, would set their team to work stifling their competitors and grabbing seconds where they could. After winning the following day’s time trial by a handful of seconds, Merckx looked to be following suit.

Indeed for the next 10 days, Merckx seemed to toy with the peloton. Stage nine saw a long-range attack by the unheralded Jacques de Bouver joined by Merckx and the second-placed Roger Pigneon. Pigneon would take the stage but the pair would gain a further two minutes on the field. A win in stage 11 and stage 15’s time trial gave Merckx an advantage of some eight minutes over Pigneon. It was enough, Merckx would be champion.

However, the 1969 Tour had one more twist. Eddy Merckx was about to paint his masterpiece. Eddy had, it seemed, a motivation beyond mere dominance. In the rider’s briefing before the race it was announced that a failed drugs test would no longer result, as in the Giro, in disqualification but, instead, in a 15-minute time penalty on the overall classification. If Eddy was to avoid a repeat of the stitch-up in Savona, he would need some buffer.

And so, on stage 17, a 214km monster that would traverse the Pyrenees, Merckx pulled out a ride that, to the modern observer, defies belief. Having crossed the Col de Peyresourde and the Aspin safely in the peloton, he grew restless, attacking on the relentless middle section of the Tourmalet and taking an elite group with him. There were 140km between Eddy and the finish in Mourenx. As the climb once again steepened in its final kilometres he accelerated again, dropping Pigneon, Raymond Poulidor and the rest. By the time he had plummeted into the Pau valley, his advantage was two minutes.

Cycling dopers

The rate in which cyclists have been involved in doping cases has decreased significantly, from 52.9% to 8.6%. However...

Since 1998, among all participants, 29% have been involved in doping cases;

Since 1998, among the top 10, 47% have been involved in doping cases;

Since 1998, among the winners, 60% have been involved in doping cases.

By the foot of the Aubisque, the next 2,000m climb on the menu, some 20km later, he was 3m 55sec ahead. At the summit it was seven minutes. There were still 75km to ride and, incredibly, his advantage remained. It was a spontaneous act of violence against his colleagues. After his erstwhile companions from the Tourmalet trailed in, the next group was 15 minutes behind Merckx. This was Merckx as tyrant, winning the world’s biggest race by the act of destroying his rivals’ spirits. He was riding as one man against six and, by the top of the Aubisque, the six were trying to limit their losses.

Merckx consolidated his advantage on the final day’s time trial in Paris, but the two minutes he gained were taken from broken men. His final account saw him 17m 54s ahead of Pingeon and 22 minutes ahead of Poulidor. Eddy Merckx took the yellow jersey, the climber’s jersey, the white jersey of best young rider and the green jersey, a feat never equalled. Ironically, the Tour finished on the same day that Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon. On French and Belgian TV that night, the screen was split. On the left-hand side was Eddy Merckx being interviewed and on the right, mankind’s giant leap.

Perhaps the even greater feat that day was that Merckx became Belgian. Arguments over which culture he belonged to became obsolete overnight as he became the country’s first Tour winner in 30 years, Flemish or Walloon. Records were produced, every kind of souvenir imaginable became immediately available, a national holiday was declared. This was to be the high tide of Merckxism. A glorious, transcendent moment of sport that revealed exactly how dominant Eddy Merckx could and would be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks