The sky’s the limit: Can green flying ever take off?

The head of one of the world’s biggest airlines has described carbon offset schemes as a ‘fraud’, writes Nick Ferris. So what should the industry be doing to tackle pollution, while causing minimal turbulence?

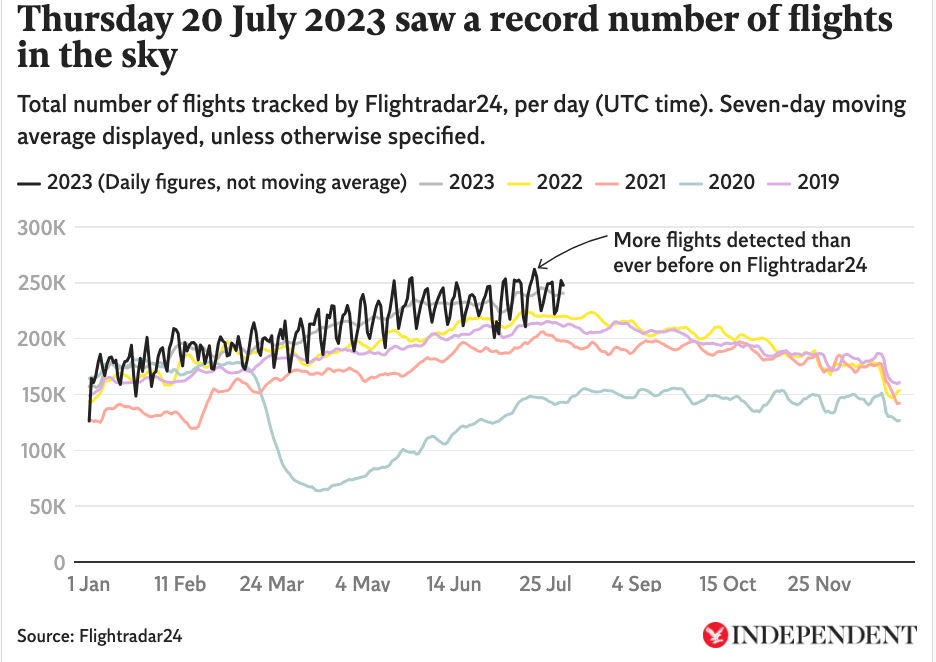

The end of last month marked an aviation milestone: on 20 July, there were more planes in the sky than ever before on a single day – 262,000 of them – as recorded by website Flightradar24.

At the same time as these kerosene-burning planes made their journeys, tens of thousands of tourists were being forced to flee holiday resorts, as wildfires fuelled by the climate crisis ripped across southern Europe.

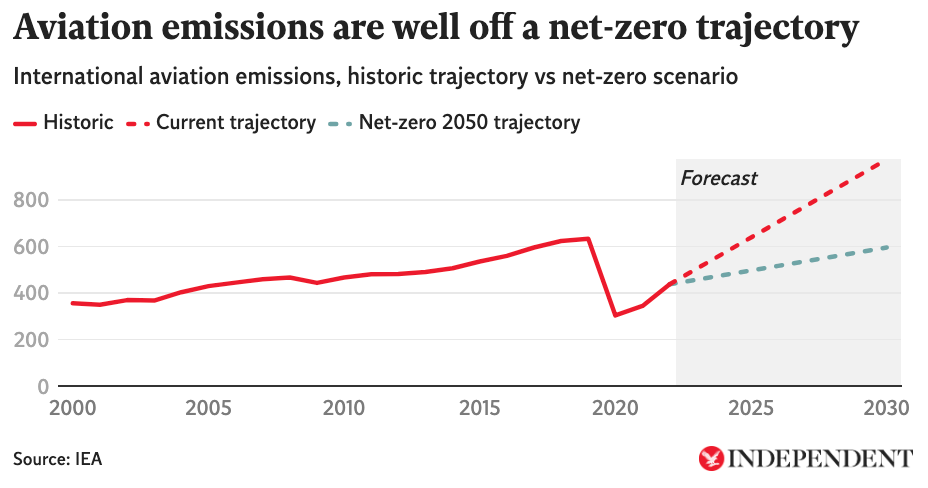

If more devastating impacts of climate change are to be avoided, then humanity’s insatiable appetite for air travel is among many areas that must be addressed as part of plans to reach net zero by 2050. However, unlike electric vehicles (EVs) for road travel, or solar and wind for electricity, aviation is – along with sectors like steel and cement – one of the hardest sectors to tackle.

The reason for this is that flying through the air requires a lot of energy, which makes energy-dense kerosene a hard fuel to substitute. Improvements in engine or aerodynamic design incrementally improve fuel performance each year, but overall aviation emissions continue to increase, because passenger growth (at around 5 per cent annually before the pandemic) continually outpaces energy efficiency growth (3 per cent).

For a tourist about to fly abroad, the most immediate means of apparently decarbonising their travel is by purchasing a carbon offset, which promises to absorb a tonne of carbon for every tonne of carbon emitted during a flight.

But a growing body of evidence makes it clear that offsetting schemes are not the panacea they promise to be: research from the non-profit Carbon Market Watch points out that the wide range in offset pricing, as well as the ignoring of non-CO2 greenhouse gases like nitrogen oxides and water vapour, all point to the inefficacy of airline offset schemes. Other recent analysis of offsets issued by Verra, a leading offset company, found that up to 90 per cent of rainforest offsets currently issued were essentially worthless.

The existence of offsets also risks psychological damage to the mission of decarbonising aviation: “If we actually want to achieve net zero, we are going to have to make big changes to both technology, as well as how much we fly”, Cait Hewitt, Aviation Environment Federation (AEF) campaign lead, told The Independent. “Offsetting, by contrast, provides false comfort that we can somehow continue business as usual”.

In July, the boss of United, the world’s third largest airline, labelled most offset schemes “a fraud”, while budget carrier easyJet announced in September 2022 that it would stop purchasing offsets, which had until then been a key pillar of its net zero strategy.

Much of the aviation industry has shifted its focus to technological solutions to decarbonise air travel, rather than attempts to remove emissions once they have been released. There are three main technological solutions: electric planes, hydrogen planes, and sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs). All three solutions hold potential, as well as significant disadvantages.

Propelled by innovation in the EV sector, every year that passes sees batteries become cheaper and more lightweight, and airlines, including Scandinavian Air, are promising very short, small-scale all-electric flights within a decade. However, batteries will in all likelihood remain too heavy to power most air travel currently covered by narrow-body or wide-body jets by 2050, according to consultant Bain & Company.

Hydrogen, meanwhile, is expected to be able to power larger flights over longer (though not long-haul) distances by 2050, and leading manufacturer Airbus has set the goal of producing its first entirely hydrogen-powered aircraft by 2035. However, hydrogen planes will require a total redesign of aircrafts, as much larger and more complex fuel tanks will be needed to cope with the leakiness and low density of hydrogen.

There would also be significant challenges around producing enough low-carbon hydrogen from renewables to meet demand, as well as major new costs: Bain puts the cost of converting just 53 airports in Europe to supplying hydrogen fuel at up to $65bn (£51bn), and estimates producing low-carbon hydrogen to fuel just 5 per cent of passenger miles flown by 2050 would cost up to $400bn (£315bn).

Jayant Mukhopadhaya, a researcher at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a non-profit organisation that provides research to regulators, adds that the “slow pace of fleet renewal” – with a typical lifespan of 35 years or more for many commercial aeroplanes – means that both hydrogen and electric could only ever have a limited impact in the 27 years between now and 2050.

It is here that sustainable fuels have their great advantage: they can be used to power existing aircraft models, with both Boeing and Airbus pledging to make their planes 100 per cent SAF compatible by 2030. Produced from a variety of sources – including from biomass, waste plastics, used cooking oils, or as artificial “e-fuels” created using renewable electricity – most national aviation decarbonisation programmes – including the government’s “Jet Zero” strategy in the UK – now prioritise SAFs over other new technologies.

But SAFs are also not without their problems. Using biomass, for example, “has indirect effects of crowding out agriculture or encouraging deforestation”, says AEF’s Hewitt. E-fuels, meanwhile, would require enormous quantities of renewables to meet current fuel demand, equivalent to two-fifths of the renewable energy currently available globally, according to calculations from Stay Grounded.

But while no single solution is perfect, that is not to say that the task of decarbonising aviation is impossible. According to Matt Finch, UK policy manager at think tank Transport and Environment, if both policymakers and companies really pushed SAFs, then there could be zero emission commercial flights by the 2030s.

“But that would only be the case if the government really went for it, with both funding and regulation”, Finch told The Independent. “Unfortunately, the UK government does not seem to be really going for it: Jet Zero targets 10 per cent SAF in airline fuel by 2030, but this figure is not mandated to increase to 100 per cent.

“The plane manufacturers are also not currently completely serious about decarbonisation. Car manufacturers are putting nearly all their R&D money into EVs, but we know that Boeing and Airbus continue to invest huge amounts in improving kerosene-powered planes”.

Finch adds that there are several significant quick wins in decarbonising aviation which are not yet mandated. These include the airline policies of tankering (carrying more fuel than is needed to save money on refuelling), and flying around certain countries, in order to avoid paying fees.

Then there is the question of trying to reduce aviation demand, which is something that the UK government has historically been averse to attempting. Campaigners, however, take a different stand, pointing to the fact that aviation emissions are too much of an unfair burden for most of the world to bear, given that an estimated 1 per cent of the world’s population emits 50 per cent of CO2 from commercial aviation, while just 2-4 per cent of people fly internationally each year.

“We cannot have a sustainable aviation sector without having a smaller aviation sector”, says AEF’s Hewitt. “We need to have more positive conversations about less business flying, and actively pursuing a national tourism policy that promotes places in the UK”.

Even if the UK government has failed to totally get to grips with the issue, there are signs of hope in the wider aviation sector.

When it comes to demand response, Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport is pioneering policies to promote other forms of transport over air travel, while the French government has moved to ban domestic flights on routes that can be travelled by train in less than two-and-a-half hours.

In the US, president Joe Biden’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act has also promised billions of dollars in subsidies to SAFs, with the long-term aim that SAFs can meet 100 per cent of aviation fuel demand at around 35 billion gallons per year by 2050.

Professor Piers Forsterm, interim chair of the UK Climate Change Committee, also stresses that aviation remains at the beginning of its decarbonisation journey, and that big changes could be around the corner.

“Other sectors know how to decarbonise but aviation doesn’t yet; but as other sectors successfully decarbonise, the pressure will mount on aviation to change”, he told The Independent. “I’ve been talking to the industry for more than 20 years, and I have recently seen a change, with talk about net zero now moving to meaningful investment decisions.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks